A Systematic Review of Musculoskeletal Injuries Sustained from Submission Techniques in Judo, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and Mixed Martial Arts

Andrew Lewis1*, Shane Price2 and Anne-Marie Hutchison3

1Physiotherapy Department, Swansea Bay University Health Board, Neath Port Talbot Hospital, UK

2Physiotherapy Department, Swansea Bay University Health Board, UK

3Physiotherapy Department, ABMU HB, Morriston Hospital, UK

Submission:October 19, 2020; Published: April 07, 2021

*Corresponding author: Andrew Lewis, Physiotherapy Department, Swansea Bay University Health Board, Neath Port Talbot Hospital, UK

How to cite this article: Andrew L, Shane P, Anne-Marie H. A Systematic Review of Musculoskeletal Injuries Sustained from Submission Techniques in Judo, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and Mixed Martial Arts. Ortho & Rheum Open Access J. 2021; 18(1): 555976. DOI: 10.19080/OROAJ.2021.18.555976

Abstract

Objective: To determine the risk of musculoskeletal injury from “submission” type finishing techniques in grappling sports (Mixed Martial Arts (MMA), Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) and Judo) in both training and competition settings.

Design: Systematic review without meta-analysis

Materials and methods: A search of published literature databases was undertaken (from their start to November 2020). Two reviewers independently assessed the studies for eligibility using a strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. All eligible articles were assessed against the Clinical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Data on cohort characteristics, number of musculoskeletal injuries, anatomical area injured, type of submission techniques causing the injury and whether the injury was sustained in training or competition were extracted. A narrative research synthesis method was adopted since there were insufficient data to conduct a meta-analysis.

Results: 787 studies were identified. Eleven publications met the review inclusion criteria (MMA n=5, BJJ n=4, Judo n=2). Methodological quality was generally poor with eight studies at a high or extreme risk of bias. No central injury surveillance database was identified for any of the sports investigated. Seven different anatomical areas were identified as sustaining injury with elbows the most common. A low risk of submission injury exists in competition equivalent to 20.8 injuries per 1000 matches. A higher risk was reported in training with 15.2% experiencing an injury in a six-month period. Time-loss following injury was reported in only one of 320 injuries.

Conclusion: There are currently no injury surveillance program in submission grappling sports to record injuries that occur during training and competition. Therefore, it is not possible to accurately investigate the prevalence of such injuries from submission techniques in MMA, BJJ or Judo. Accurate databases which record type and severity of injury are required to determine if submission techniques are harmful in both the short and long term. Databases should also record time-loss following injury and volume of injury free sport to enable accurate calculation of risk versus athletic exposure.

Keywords: Submission techniques; Joint lock; Muscular force; Injury patterns

Introduction

Submission wrestling, also known as submission grappling, is a form of competition and a general term for martial arts and combat sports that focus on clinch and ground fighting with the aim of obtaining capitulation using “submission” techniques. Common examples of such sports include Judo, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) and Mixed Martial Arts (MMA). They are high contact, aggressive and physically demanding activities, where the contest ends when a competitor concedes defeat by “tapping out”, i.e., visibly tapping the floor or the opponent with the hand or saying the word “tap” to signal to the opponent and referee of the submission. These sports are gaining increasing popularity. MMA has been described as the fastest growing sport in the world with an estimated 450 million followers (https://immaf.org/about/) and is now more popular than boxing in males aged 18-34 [1,2]. This increase in popularity is reflected in the potential financial gains which can be made at a professional level, where MMA athletes can earn more than $10m during their career.

Submission techniques are designed to threaten joint injury

or unconsciousness in an opponent. A joint lock takes a particular

joint of the opponent to its physiological end range then applies

additional force to achieve a submission prior to severe injury

or intolerable pain. Competitors often attempt to escape such

submissions as they are being applied but this is dependent on

precise timing often combined with considerable muscular force

from both competitors, at the joint end range (see appendix 6

for YouTube examples). Submission techniques and escapes

are by their nature potentially harmful and submitting to them

is an instant loss. With professional rankings, Olympic medals

and significant financial rewards at stake there can be a strong

incentive to resist submitting which may further increase the risk

of danger and harm.

Recently there has been growing attention on reporting

significant long-term injuries and opportunities for prevention in

contact sports. Implementing robust injury surveillance programs

has been vital to ensure optimal athlete safety in rugby and boxing

[3,4]. Such data led to coach education programs in rugby reducing

moderate to serious injuries by 15% [3]. Conversely large-scale

surveillance in amateur boxing showed no association to serious

health concerns defining it as a safe sport and not requiring any

changes [4].

A review of the databases PUBMED, MEDLINE, EMBASE and

Science Direct (from their start until November 2020) on injury

patterns in grappling sports from any mechanism found several

studies [5-7]. However, no systematic review has been performed

looking specifically at submission injuries sustained in these

sports. Different rules across such sports make comparison of risk

and injury rates difficult. For example, a common cause of injuries

in MMA are facial injuries from punches and kicks to the head [8]

yet these techniques are not permitted in either Judo or Brazilian

Jiu-jitsu (BJJ). Whilst the main submission-based sports of Judo,

BJJ and MMA have rules to minimize the risk of submission injury,

it is unclear if they are effective or appropriate. Given a recent

International Olympic Committee consensus statement on injury

surveillance [9] the increasing popularity of grappling sports and

MMA, with the potential for athlete harm, an investigation into the

literature on submission injuries in these sports is required.

The aim of this review was to determine the injuries that may

be occurring from joint submission techniques, including the

common anatomical joints and structures at risk, if any specific

submission technique had a higher prevalence of injury, the

severity of such injuries including time-loss and the quality of the

available literature.

Materials and Method

Data source

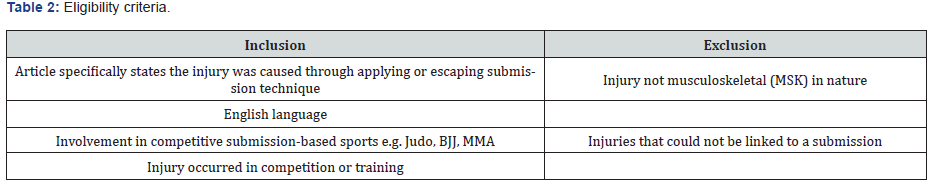

The electronic databases PUBMED, MEDLINE, EMBASE and Science Direct were searched in November 2020 from the start of the databases to present. Keywords searched and search strategy are presented in Table 1 with inclusions and exclusions in Table 2.

Eligibility Criteria

All observational studies (case control, cross-sectional and cohort studies) which had investigated grappling submission injuries and were in the English language where included. Articles including technical notes, letters and personal opinions were excluded.

Methods of Review

Studies were independently assessed for inclusion by two reviewers (AMH and AL). The reviewers evaluated all identified titles and abstracts after duplications removed, independently against the inclusion criteria. The remaining articles were assessed based on their full texts, if additional studies were identified from the reference lists they were also requested and assessed leading to the sample of eligible articles. PRISMA guidelines were followed throughout the review [10].

Data Extraction

Data extraction for each eligible paper was performed independently by two reviewers (AMH and AL) using a prepared data collection sheet. Data extraction included: grappling sport, population characteristics (sample size, age, gender), duration of data collection, number of MSK injuries, injury rate per 1000 athletic exposures, joint affected, specific anatomical structure injured, type of submission techniques used and whether the injury occurred in competition or training.

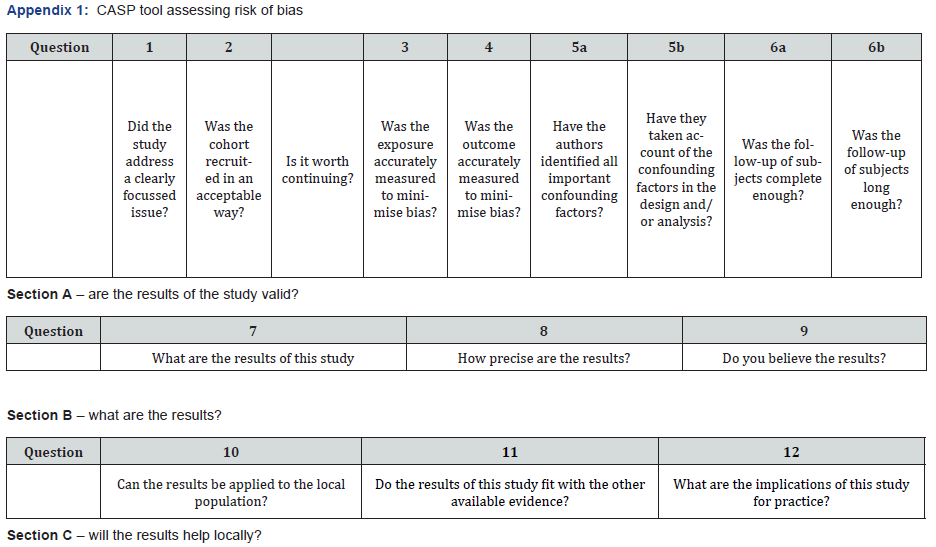

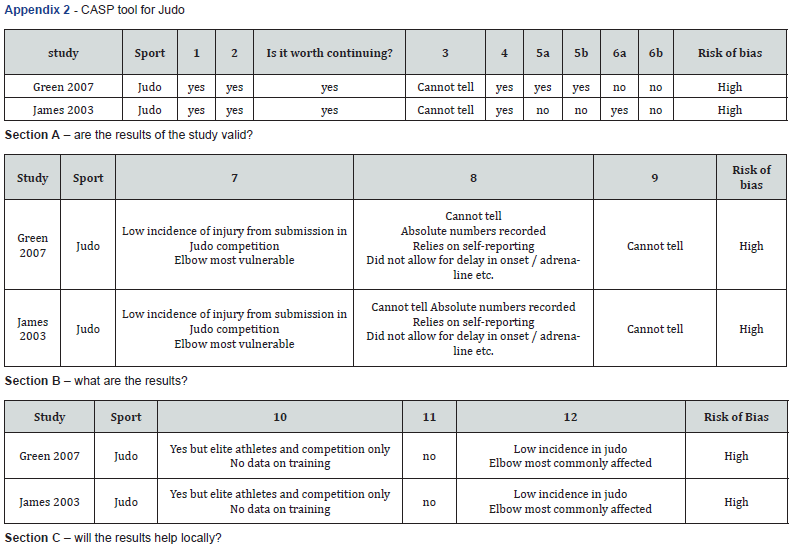

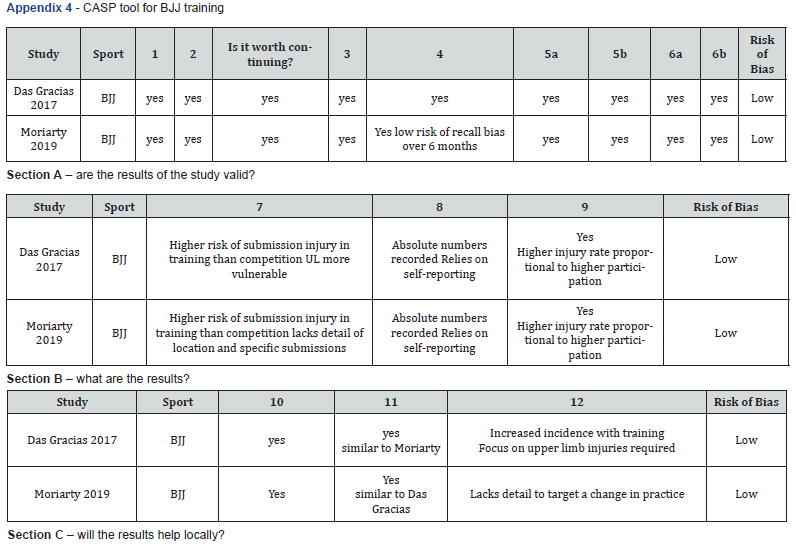

Critical Appraisal

Despite a high volume and variation of critical appraisal tools

for observational studies, no single gold standard tool has been

identified that critiques epidemiological studies [11]. The Clinical

Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) developed in 1993 offers

individual tools for different study designs therefore enhancing

specificity [12]. Users are guided through 12 questions in three

sections supporting the critical analysis of results validity, results

interpretation and the applicability of outcomes. Unlike other

tools such as the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro)

[13], no numerical / hierarchal score is given by CASP as not all

questions carry equal importance. CASP is free to access, easy to

use and assesses risk of bias in domains as recommended by the

Cochrane Collaboration with adherence to CASP found to enhance

conclusions [12,14]. The CASP Cohort tool was therefore selected

to enhance the validity of this review’s conclusions.

As CASP assesses bias in three broad categories of results

validity, results interpretation and outcome applicability a scoring

system was developed by author consensus to enable comparison

between studies with clearer objectivity of the risk of bias. Each

study was classified as having an overall low, medium, high or

extreme risk of bias with a low risk optimal.

Results

Search strategy

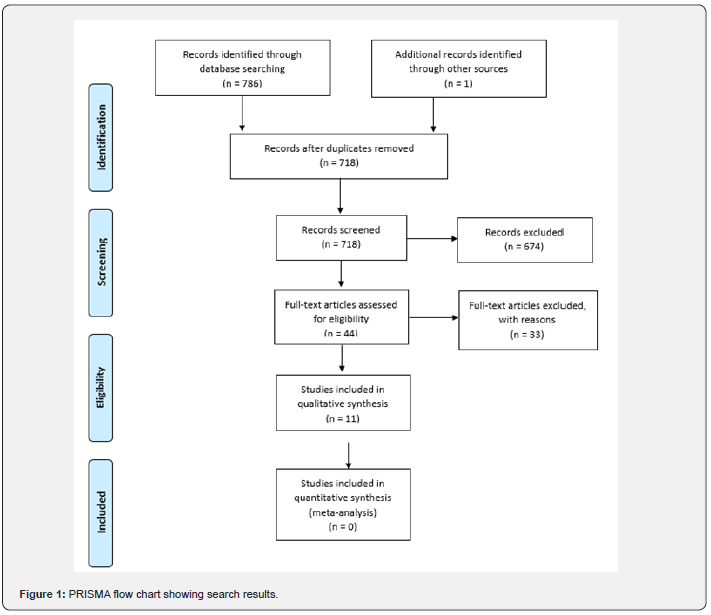

A total of 787 articles were identified with 69 duplicates leading to 718 unique titles. Their titles and abstracts were reviewed by two authors (AMH and AL) against the eligibility criteria specified in Table 2 leaving 44 requiring assessment of the full text. 33 studies were excluded based on their full text. The most common reasons were the cause of injury not detailed (n=16), injuries were detailed but not from a submission e.g. a throw (n=8), the studies were systematic reviews of papers already identified by this search (n=4). Other reasons included two studies not published in English, one paper was unobtainable, one article collected the relevant data however did not publish the full data set. The lead author was contacted by email to request that data but did not respond. The final excluded paper detailed one submission injury but did not report if it was during Judo or BJJ. That injury could not be assigned to either sport or as there was a low risk of that single injury affecting the outcomes of the review it too was excluded. Eleven articles were included in the final analysis (PRISMA flow chart Figure1).

Data Extraction

Data extraction for each eligible paper was performed independently by two reviewers (AMH and AL) using a prepared data collection sheet, see Table 3.

ACJ – acromioclavicular joint, ACL – anterior cruciate ligament, AE – athlete exposure, ATFL – anterior talo-fibular ligament, BJJ – Brazilian Jiu-jitsu, comp – competition, MCL – Medial Collateral ligament (knee), MMA – Mixed martial arts, MSK musculoskeletal, NR – not reported, RCL – radial collateral ligament (elbow), retro – retrospective, UCL- Ulna collateral ligament (elbow), UTA – unable to assess, / 1000 AE – incidence of injury per 1000 athletic exposures.

Data Analysis

Due to the variation in injury reporting methods, data capture, follow-up periods and different rulesets across BJJ, Judo and MMA a meta-analysis was not appropriate. A descriptive analysis was therefore performed.

Study Design

Eleven studies including nine observational cohorts, one case series and one case study were included. The duration of data capture varied from a single day of competition (n=2 both Judo) to a 10-year retrospective analysis (MMA). The method of data capture was variable and included attendance to an emergency department (n=1), review by medical support team at the event (n=6), retrospective analysis of televised matches (n=1), retrospective analysis of athletic event records (n=1) or online survey (n=2).

Sport and competitive distribution

The distribution by sport of 11 articles were Judo n=2 (2= competition, 0=training), BJJ n=4 (2 =competition, 2= training) and MMA n=5 (4= competitions, 1= unreported).

Population characteristics

A total of 10,372 subjects aged 12-51 years were included in this review. Five studies did not report age range, six did not report mean age with only one study including participants aged under 18. Studies included participant numbers from 1 to 5022 with the mean and median of 943 and 392, respectively. Males predominated all studies (male in Judo 69.7%, BJJ 84%, MMA 96.7%).

Injuries

A total of 185 musculoskeletal injuries were reported in 8891

competitive athlete exposures (matches) representing submission

injury rate equivalent to 20.8/1000 matches. The duration of each

match was not available and may vary between a few seconds and

15 minutes. Training injuries were only reported in BJJ, with 140

submission injuries in 1480 athletes with one study reporting

13.0% and a second reporting 15.2% of competitors had suffered

at least one submission injury in a 6-month period [15,16]. Data

was not presented on total training hours to enable injury rate to

be calculated per 1000 hours. A direct comparison of injury risk

between competition and training was therefore not possible.

The elbow was the most frequently injured joint in all sports

(elbow n=97, shoulder n=21, ankle n=15, knee n=7, wrist/hand

n=3, lumbar and cervical spine n=1 each). Four of the 11 studies

reported the anatomical structure injured detailing 29 structures

in 24 competitors. The distribution of injuries at the elbow were

11 UCL, two RCL, one combined UCL/RCL, one distal bicep strain,

one subluxation, three olecranon tenderness and three microfractures.

One sprain of the acromioclavicular joint and one

cervical spine sprain were also reported in the upper body. Lower

body injuries included one Achilles contusion, one ATFL sprain and

one knee injury involving both the ACL and MCL. The severity of

injury was only reported in two studies (6 competitors) included

five complete UCL ruptures at the elbow and a complete rupture

of the ACL at the knee combined with partial rupture of the MCL.

The highest occurrence of submission injury was in MMA and

the most frequent submission leading to injury in all three sports

was the “armbar”. Time-loss following injury was only reported

for one injury out of the 320 included in this review. A female Judo

competitor lost 1 week of training following an un-named elbow

submission.

Critical Appraisal

The findings of the critical appraisal (CASP tool) are summarized in Table 3. Only two studies had a low risk of bias [15,16], one study demonstrated a medium risk of bias [17] and 8 were of high or extremely high risk of bias [2,5,18,19,20-23]. The literature highlighted several methodological limitations including under-reporting of exposure, insufficient follow-up, not reporting if the injury was sustained in competition or training and only reporting injury at elite level adult competition. Female competitors, competitors under the age of 18 and amateur / nonelite level competitors are underrepresented in this review.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to determine the injuries that

may be occurring from submission techniques including the

common anatomical joints and structures at risk, if any specific

submission technique had a higher prevalence of injury, the

severity of such injuries including time-loss and the quality of the

available literature. To our knowledge this is the first review that

has exclusively examined submission injuries affecting the joints

in grappling sports. The inclusion criteria of the review were

not strict to account for the paucity of literature on this topic.

However, despite this just 11 studies met the inclusion criteria

and were investigated.

Due to the heterogeneous nature of the studies, it was not

possible to conduct a meta-analysis to assess the musculoskeletal

injuries sustained from submission techniques. The results of

the studies could only be analysed descriptively. No definitive

conclusions could therefore be drawn regarding the incidence,

anatomical location and type of injury as well as the severity and

long-term consequences of injury. The review also revealed that

the methodological quality of most studies (n=8/11) were poor

further affecting the ability to draw any conclusions.

Taking into consideration the above limitations the studies

included in this review show a trend that incidence of submission

injuries in training is far higher than in competition. Differences

in reporting method prevent direct comparison however an

injury rate of 20.8 per 1000 competition matches was compared

to between 13.0% and 15.2% of competitors experience a

submission injury in a six-month period whilst training. This

may reflect the presence of the referee in competitions. Another

explanation is that competitors will typically train for 3 or more

hours per week (over 150 hours per year) and compete twice per

year amassing less than one hour of total competition with a third

choosing never to compete [18]. Therefore, competitors may be

exposed to injury 150 times more in training than in competition.

This review suggests submission grappling sports are male

dominated with just 5 of the 11 studies in this review including

females. It is difficult therefore to draw from this study whether

there is a relationship between gender and the type of submission

injury sustained. The most injured joint was the elbow (n=97) followed by the shoulder (n=21), ankle (n=15), knee (n=7), wrist

(n=3), lumbar spine (n=1) and cervical spine (n=1). All injuries

were from joint locks except one from a strangulation technique (a

technique called a “triangle”) in a BJJ competition. This accounted

for the one cervical spine injury and was diagnosed as a cervical

sprain [20].

The most frequently reported joint sustaining injury via

submission techniques is the elbow via the “armbar”. A sprain

/ rupture of the ulna collateral ligament (UCL) was the most

reported injury [17,23]. In a case series of 5 injuries due specifically

to the armbar in BJJ, MRI investigation found all had sustained

complete UCL rupture with 60% also sustaining contusion and

microfracture to the olecranon or distal humerus [17]. This is

not surprising given an investigation of structural strength at the

elbow found the UCL to have lower tensile strength than the distal

bicep or proximal ulna therefore predicting failure of the UCL

initially [24]. Clinicians should always consider assessment of this

UCL when competitors present with an elbow injury following an

armbar submission.

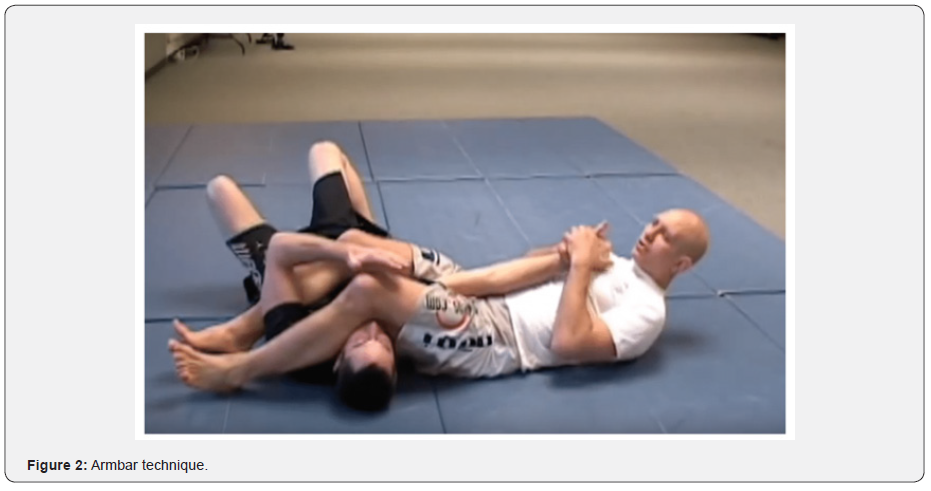

The “armbar” was the most common submission leading

to injury in this review (Figure 2). The practitioner (dressed in

white) takes the right elbow of his opponent (dressed in black)

to the end of its physiological extension range then applies an

additional hyperextension force through active hip and lumbar

spine extension until submission or structural failure (YouTube

examples provided in appendix 6).

Only five studies reported the specific named submissions

leading to injury including only six different submission

techniques (armbar, kimura, triangle choke, footlock, heel hook,

Achilles lock). The total number of possible submissions available

to competitors is greater than 30 different techniques (SP). As

a consequence, there is currently no complete reliable data on

actual injury rate during either competition or training across all

submissions.

All eight studies reporting injuries sustained in competition

used event only reporting. Competitors may lose a contest

through a submission causing a lower-grade joint or ligament

injury. As most tournaments are of knock-out formula the athlete

may often leave the venue shortly following their defeat. Due to

a combination of competition adrenaline and the delay in onset

of an inflammatory response the impact of an injury may not be

immediately apparent. Event injury reporting may therefore under

report such injuries. It was difficult to determine from the review

the severity of injury and the potential long-term consequences of

injuries. Time-loss was only reported in one injury. A female elite

Judo athlete returned to full training in less than 1 week following

an armbar submission. The number of injuries leading to athletes

choosing to leave the sport has also not been reported in any

included study.

Accurate data on injury reporting and time-loss are a

significant factor in a competitor’s decision-making process on

when to submit and when to risk potential injury. A short period

of time-loss may encourage competitors to take more risks. A

longer recovery, prolonged rehabilitation or surgery would likely

dissuade such risk taking. In a survey of BJJ injuries (mechanism

not reported) athletes with greater than 4 months of time loss from sport were 5.5 times more likely to consider leaving

the sport and 19 times more likely to require surgery with no

association to level of experience [7]. A difference may also exist

between professional and recreational athletes. For a recreational

participant, a significant sports injury may impact on their

regular employment and means of income. Such an injury could

have a large financial impact, especially if self-employed, possibly

contributing to their willingness to risk injury. In contrast to

professional athletes where injury with potential quality of life

consequences may be risked if a large amount of prize money is

at stake.

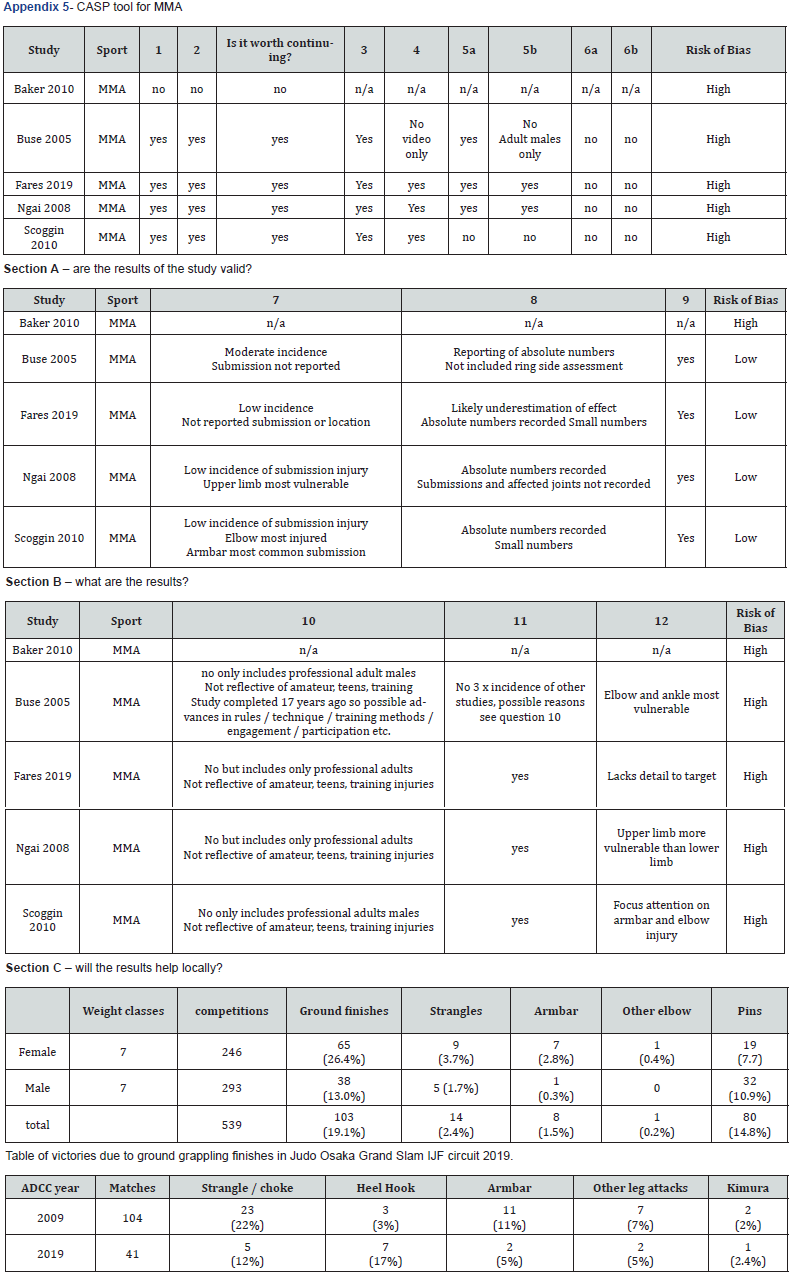

The low incidence of submission injury in Judo competition

was the lowest of the three included sports which may be due

to infrequent use of submission attacks in elite competition. The

authors (SP and AL) reviewed the outcome of all 539 matches

between 481 Judo athletes from 87 countries of the Osaka Judo

Grand Slam event in 2019 (breakdown in appendix 6). The only

joint submission allowed in Judo are elbow attacks representing

3.2% of all wins in the female categories and only 0.3% in males.

This infrequent use of such techniques in modern elite Judo may

explain the low injury risk in competitions from submissions.

The ADCC (Abu Dhabi Combat Club) Submission Wrestling

World Championship is a biennial event representing the highest

level of elite multi-discipline grappling. Matches from 2009 and

2019 were reviewed retrospectively by two authors (SP and AL)

and illustrated a change in techniques and tactics used at this

highest level. In 2009 the armbar was responsible for 11% of

victories, all leg attacks were 10% of which 3% were from heel

hooks. In 2019 the armbar was less frequent accounting for 5% of

finishes with leg locks rising to 22% and heel hooks alone 17% of

all submissions (breakdown in appendix 6). The articles reviewed

in this study were published at a median date of 2012 (not

including the two Judo articles as leg attacks are forbidden). This

observed change in tactics may therefore not be reflected in this

review and this review has not been able to assess if an increasing

use of the heel hook is associated with an increased frequency

or severity of injury. A complete UCL rupture at the elbow from

an armbar [16] and an anterior cruciate ligament rupture from a

heel hook [21] are both highly significant injuries often requiring

surgical correction and lengthy delays before returning to sport.

The most striking aspect of the review is there is currently

no official reporting / surveillance system for monitoring

injuries from submission techniques. Implementing robust injury

surveillance programs has been vital to ensure optimal athlete

safety in contact sports including rugby and boxing [3,4]. Injury

surveillance provided data leading to coach education programs

in rugby reducing moderate to serious injuries by 15% in New

Zealand [3]. Conversely large-scale surveillance in amateur boxing

showed no association to serious health concerns defining it as a

“safe sport” and not requiring rule changes [4]. Implementing such

surveillance is feasible to even large-scale events (recording cause

of injury and time-loss) representing a basic duty of care. Given the

poor quality of literature in this area and the lack of conclusions

that are currently able to be drawn around submission injuries,

the authors would encourage the international governing bodies

of popular submission based grappling sports (International

Judo Federation, International Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation,

and International Mixed Martial Arts Federation) to invest in

injury and illness surveillance programs as recommended by the

IOC consensus statement [9]. Such programs will provide large

volumes of data for analysis to ensure athlete health is optimised

and any changes, if necessary, can be robustly justified. This data

will help with the safe evolution of the rules in these sports, if

required.

This review has highlighted a potential for significant

musculoskeletal injury from submission techniques and the

number of injuries in competition appears to be low. Unfortunately,

such reporting of injuries sustained were at high to extreme

overall risk of bias making conclusions from available literature

unreliable. There is insufficient volume and quality of research to

suggest a change to the rulesets of included sports and certainly

the authors do not recommend such changes. Just as suggestion

from governing bodies that removing head shots from boxing

would dramatically change the spirit of the sport, so too would be

the impact of removing submissions from grappling sports.

Limitations

No meta-analysis could be performed due to the heterogeneity of rulesets and potential under-reporting of injuries. Studies included were generally at high and extreme risk of overall bias. The injury risk and prevalence in training is under-represented in this review as only two studies (including 14.3% of the total subjects) investigated injuries in training. Only one injury was reported from a strangulation technique therefore, no conclusions can be drawn around this group of techniques.

Conclusion

The main findings of this review are that there is currently no surveillance or official databases available to determine the true incidence, type and severity of injury from submission techniques from both competition and training. The studies conducted are mainly of poor methodical quality and therefore it is not currently possible to draw any conclusions around the safety of submission techniques. In conclusion BJJ, Judo and MMA have a low incidence of injury through submission techniques in competition of 7, 12.5 and 33 per 1000 matches, respectively. Training injuries were only reported in BJJ, between 13.0% and 15.2% of BJJ athletes reporting at least one injury in a six-month period. Governing bodies should strongly consider implementing injury and illness surveillance programs to further inform this under-researched topic and maintain athlete health.

Table of submission finishes in ADCC tournament in 2009 and 2019. YouTube examples or armbar and heel hook submissions used in competition Compilation of armbars in Judo competition: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HOOSxtw7lRI Armbar defended at 7min 30sec: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOfCfsg76eY Armbar injury at 55sec: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kMeHW-mYJxU Heel hooks in competition (ADCC): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GwoYcWM66_M Heel hooks in MMA: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jIZRE9ivcec

References

- Ross, DJ, Tudor GJ, Hafner JW, Yahuaca BI, Wang H (2013) Injury patterns of mixed martial arts athletes in the United States. Annals of Emergency Medicine 4(62): S108.

- Ngai KM, Levy F, Hsu EB (2008) Injury trends in sanctioned mixed martial arts competition: a 5-year review from 2002 to 2007. British journal of sports medicine 42(8): 686-689.

- Freitag A, Kirkwood G, Pollock AM (2015) Rugby injury surveillance and prevention programmes: are they effective? bmj, 350.

- Bianco M, Loosemore M, Daniele G, Palmieri V, Faina M, et al. (2013) Amateur boxing in the last 59 years. Impact of rules changes on the type of verdicts recorded and implications on boxers’ health. British journal of sports medicine 47(7): 452-457.

- Fares MY, Fares J, Fares Y, Abboud JA (2019) Musculoskeletal and head injuries in the ultimate fighting championship (UFC). The Physician and sports medicine 47(2): 205-211.

- Frey A, Lambert C, Vesselle B, Rousseau R, Dor F, et al. (2019) Epidemiology of judo-related injuries in 21 seasons of competitions in France: a prospective study of relevant traumatic injuries. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine 7(5): p.2325967119847470.

- Petrisor BA, Del Fabbro G, Madden K, Khan M, Joslin J, et al. (2019) Injury in Brazilian jiu-jitsu training. Sports health 11(5): 432-439.

- Bledsoe GH, Hsu EB, Grabowski JG, Brill JD, Li G (2006) Incidence of injury in professional mixed martial arts competitions. Journal of sports science & medicine 5(CSSI): 136-142.

- Bahr R, Clarsen B, Derman W, Dvorak, J, Emery CA, et al. (2020) International Olympic Committee Injury and Illness Epidemiology Consensus Group. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: methods for recording and reporting of epidemiological data on injury and illness in sports 2020 (including the STROBE extension for sports injury and illness surveillance (STROBE-SIIS)). Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine 8(2): p.2325967120902908.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, et al. (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Journal of clinical epidemiology 62(10): e1-e34.

- Katrak P, Bialocerkowski AE, Massy Westropp N, Kumar VS, Grimmer KA (2004) A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools. BMC medical research methodology 4(1): 1-11.

- Singh J (2013) Critical appraisal skills programme. Journal of pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics 4(1): 76.

- Elkins MR, Moseley AM, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Maher CG (2013) Growth in the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) and use of the PEDro scale 47(4): 188-189.

- Bradley P, Burls AJ (1999) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: a project in critical appraisal skills teaching to improve the quality in health care. Journal of Clinical Governance-Leicester 7: 88-91.

- Das Graças D, Nakamura L, Barbosa FSS, Martinez PF, Reis FA, et al. (2017) Could current factors be associated with retrospective sports injuries in Brazilian jiu-jitsu? A cross-sectional study. BMC sports science, medicine and rehabilitation 9(1): 1-10.

- Moriarty C, Charnoff J, Felix ER (2019) Injury rate and pattern among Brazilian jiu-jitsu practitioners: A survey study. Physical therapy in sport 39: 107-113.

- De Almeida TBCD, Dobashi ET, Nishimi AY, Almeida Junior EBD, Pascarelli L, et al. (2017) Analysis of the pattern and mechanism of elbow injuries related to armbar-type armlocks in jiu-jitsu fighters. Acta ortopedica brasileira 25(5): 209-211.

- Green CM, Petrou MJ, Fogarty Hover ML, Rolf CG (2007) Injuries among judokas during competition. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 17(3): 205-210.

- James G, Pieter W (2003) Injury rates in adult elite judoka. Biology of Sport 20(1): 25-32.

- Scoggin III JF, Brusovanik G, Izuka BH, Zandee van Rilland E, Geling O, et al. (2014) Assessment of injuries during Brazilian jiu-jitsu competition. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine 2(2): 2325967114522184.

- Baker JF, Devitt BM, Moran R (2010) Anterior cruciate ligament rupture secondary to a ‘heel hook’: a dangerous martial arts technique. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy 18(1): 115-116.

- Buse George J (2006) No holds barred sport fighting: a 10-year review of mixed martial arts competition. British journal of sports medicine 40(2): 169-172.

- Scoggin 3rd JF, Brusovanik G, Pi M, Izuka B, Pang P, et al. (2010) Assessment of injuries sustained in mixed martial arts competition. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 39(5): 247-251.

- Lonsdale L, Deamer K, Lieu E (2014) What happens if an arm lock goes too far? Journal of Interdisciplinary Science Topics, 2: 13.