Surgical Outcome and Satisfaction Rate of Microlumbar Discectomy in Teaching versus Non-Teaching Hospital Patients

Zahra Akbari1, Farzad Omidi-Kashani2*, Farideh Golhasani Keshtan3 and Ali Parsa4

1MD, Orthopedic Department, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Iran

2Associate Professor of Orthopedic, Orthopedic Department, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Iran

3MSC of Physiology Research, Administrative Assistant, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Iran

4Assistant Professor of Orthopedic, Orthopedic Department, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Submission:August 04, 2020; Published: August 27, 2020

*Corresponding author: Farzad Omidi-Kashani, Orthopedic Department, Imam Reza Hospital, Imam Reza Square, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

How to cite this article: Farzad Omidi-Kashani, Orthopedic Department, Imam Reza Hospital, Imam Reza Square, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. 10.19080/OROAJ.2020.16.555949

Abstract

Introduction: there is a general impression that surgeries performed in private non-teaching relative to public teaching hospitals have a higher therapeutic outcome.

Aim: We aimed to compare surgical outcome and satisfaction rate of microlumbar discectomy in the patients with refractory lumbar disc herniation in teaching versus non-teaching hospitals.

Patients and Methods: In this retrospective study, we assessed 176 patients who had been treated with simple microlumbar discectomy from April 2018 to December 2019 in a teaching university and a private non-teaching hospital (88 patients in each group) with a follow-up limitation of 6 to 24 months. The main operating surgeon and surgical technique were the same in both hospitals. Pain, disability, and the patient’s satisfaction were assessed by visual analogue scale (VAS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), and Macnab questionnaires, respectively. We used student’s t-test and Chi-Square for statistical analysis.

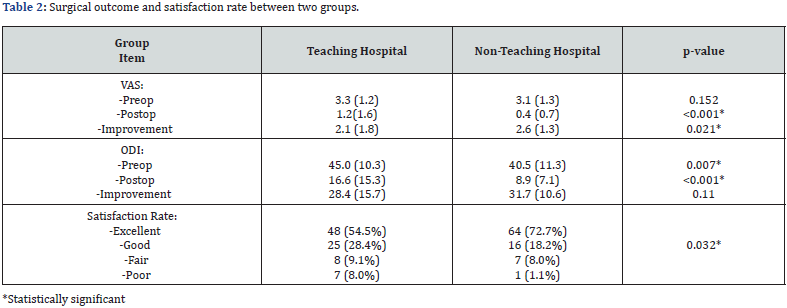

Results: The two groups were homogenous preoperatively in the terms of age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and pain, but preoperative disability was higher in teaching group (ODI: 45±10.3 versus 40.5±11.3). At the last follow-up visit, pain, disability, and satisfaction rate were all more pleasant in private group, significantly (VAS: 0.4±0.7 vs. 1.2±1.6, and ODI: 8.9±7.1 vs. 16.6±15.3).

Conclusion: Comparison of surgical outcome and satisfaction rate of microlumbar discectomy between non-teaching versus teaching hospital showed that postoperative pain and disability, and satisfaction rate were all more pleasant in non-teaching private hospital. It seems that surgical outcome and patient’s satisfaction rate of these patients may be at least partially affected by some non-surgical issues.

Keywords: Teaching Hospital; Non-teaching hospital; Lumbar Discectomy; Outcome Assessment; Patient Satisfaction

Introduction

Surgical training requires practical work on the patient’s bedside. Since maintaining the patient’s safety and health is the main basic principle of medical practice, one of the concerns of the faculty members has always been to establish a suitable educational environment while maintaining safety for the patients. It is commonly thought that resident participation in the surgical procedure not only increases the density of the operating room staff and its consequent complications, but also her/his insufficient surgical skills may lead to increased surgical unpleasant adverse effects. However, scientific studies have not been able to prove existence of a strong link between resident participation in the operating room and an increase in complications [1-4].

It seems that the difference in treatment results between teaching and non-teaching hospitals is not simply related to the presence of the resident, and various other factors including patient’s insurance status, cultural and educational level, job satisfaction, and etc. are also important and effective [5-8]. Apparently, a combination of these factors has led to a general impression that surgeries performed in private hospitals relative to public teaching hospitals have a higher therapeutic outcome. In this study, we aimed to compare surgical outcome and satisfaction rate of simple lumbar discectomy in the patients with refractory lumbar disc herniation who were operated in teaching public versus non-teaching private hospitals.

Material and Methods

In this longitudinal retrospective study, after institutional review board approval (record number: 970252, ethical code: IR.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1397.613), we assessed our patients who had been treated with microlumbar discectomy from April 2018 to December 2019 in a teaching university hospital (Imam Reza Hospital; group A) and in a private non-teaching hospital (Razavi Hospital; group B) in Mashhad, Iran. Criteria for entry into the study included those patients with single-level lumbar disc herniation (L4-L5 or L5-S1 level), primary surgery, and age limitation between 20 and 60 years old. Those cases with revision surgery, multi-level lumbar disc herniation, cauda equina syndrome, operation with instrumentation or fusion, or followup period not limited to 6 to 24 months were excluded from the study.

After the patient was admitted, informed consent assigned and all the preoperative measures were carried out, they underwent microlumbar discectomy. The main operating surgeon and surgical technique were the same in both hospitals. The orthopaedic resident who was present during the operation in the teaching hospital only acted as an assistant surgeon and did not perform surgery independently. After surgery, the patient was usually kept hospitalized one night and discharged the next day after he/she could freely walk and urinate.

Pain and disability at preoperative period and the last followup visit were assessed by two questionnaires: Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), respectively [9,10]. In evaluating pain based on VAS, we used a linear range of 0 to 10 that the patient should mark the appropriate level based on the severity of the pain. Mousavi et al. has already cross cultural translated and validated ODI questionnaire for Iranian patients [11]. Patient satisfaction at the last session was also assessed by Macnab questionnaire and graded as excellent, good, fair, or poor [12]. As the intervertebral disc degeneration is an age-related process and this process continues throughout the life, we chose only 6 months to 2 years after surgery as a postoperative period for evaluating our patients’ satisfaction and surgical outcome. Statistical analysis- After data collection with the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), the data were analysed. Quantitative data, such as age, weight, height, BMI, ODI and pain were evaluated by the student’s t-test method. Qualitative data, such as gender and surgical satisfaction were analysed by the X2 test (Chi-Square). P < 0.05 was assessed as significant.

Results

Finally, 176 patients were eligible for our study, of which 88 belonged to public (group 1) and 88 to private (group 2) hospital. Demographic characteristics of the patients were depicted in Table 1. Preoperatively, the two groups were homogenous in terms of age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and pain, but preoperative disability was more severe in teaching hospital patients (p: 0.007). Pain and disability were improved in both groups (Table 2). At the last follow-up visit, both pain and disability were more pleasant in private group, statistically. The amount of pain and disability improvement were also greater in private group, although the pain improvement only showed a statistical difference. The status of subjective satisfaction with surgery was also more favourable in the group of private patients.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we studied the surgical outcome and satisfaction rate of microlumbar discectomy as the most prevalent spine surgery among private and public teaching hospitals and found that at the last follow-up visit, postoperative pain and disability were higher while satisfaction rate was lower in teaching group.

In this study, although the main operating surgeon, surgical technique and equipment were the same, but the surgical outcome and satisfaction rate showed significant differences. Previous studies have shown that just having a resident during surgeries does not increase the risk of complications [2-4]. It seems that other issues comprising insurance status, mental, marital, income, educational level, heavy physical occupation, smoking, and the patients’ level of cooperation in following the postoperative orders should be effective in outcome of microlumbar discectomy [5-8]. On the other hand, intraoperative complications including length of operation, intraoperative blood loss, dural tear, wrong level, wrong side, and neurologic injury may have important effects on surgical outcome of microlumbar discectomy [13,14]. In the patients with lumbar disc surgery, appropriate following of the postoperative protocols comprising lifestyle modifications, body mass index correction, and proper rehabilitation program is mandatory to improve the clinical outcome [15]. It is probable that a lower level of psychological state, culture and literacy associated with lack of appropriate financial and insurance level were effective in increasing postoperative illness and dissatisfaction in the teaching hospital patients [16]. In this study we did not assess these important details and just investigated the surgical outcome and satisfaction rate.

Chua et al. in a prospective study evaluated the effect of public and private hospital systems on 420 cases with pancreatoduodenectomy [17]. They found that although the length of operation, intraoperative blood loss, and perioperative blood transfusion were higher in teaching hospital, hospital type had no significant relation with morbidity, mortality, or perioperative outcomes. This study mainly assessed perioperative outcome of pancreatoduodenectomy, while our study focused on long-term postoperative results and satisfaction rate of the operated patients and in that sense, public hospital patients had a worse prognosis in our study.

Like our study, Spaziani and co-authors compared the outcome of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy in teaching versus private hospital [18]. According to their findings, length of operation and postoperative complications were higher in teaching hospital patients. We did not assay the length of operation or postoperative complications, but the postoperative morbidity including pain and disability were similarly higher in teaching group.

Unger et al. in another comparative study, measured surgical outcome of hysterectomy three months after surgery by a healthrelated quality-of-life outcomes questionnaire in two groups of women: 50 underinsured teaching versus 50 insured private hospital patients [19]. They found that although, most of the patients achieved complete symptom relief for the conditions for which they underwent hysterectomy, the high-income insured patients at the private hospital had a more pleasant outcome satisfaction score than the teaching hospital. Three months after surgery, the women in teaching hospital reported more tired, moody, depressed, less satisfied with preoperative information they had received, and less eager to recommend hysterectomy to a friend with similar problems. The results of this study were in line with our study; both of them showed that surgical outcomes were better in private hospital patients than in public ones, although we did not assess insurance, educational, and cultural status of the patients.

Our study has several major shortcomings. First, this study was a retrospective study and naturally has the inherent disadvantages of retrospective studies. Second, we did not assess intraoperative complications. Logistically, the difference between incidence of intraoperative complications in private versus public hospital may create differences in postoperative surgical outcome and patients’ satisfaction. Third, we did not pay attention to the personal characteristics of these two groups of patients including literacy level, insurance, income, marital, and mental status. These indices may have substantial role in ultimate postoperative outcome and the patient satisfaction with this peculiar type of surgery.

Conclusion

In conclusion, comparison of surgical outcome and satisfaction rate of microlumbar discectomy between private non-teaching versus public teaching hospital showed that postoperative pain and disability, and satisfaction rate were all more pleasant in non-teaching private hospital. It seems that surgical outcome and patient’s satisfaction rate of these patients may be at least partially affected by some non-surgical issues.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran for their financial support. This project was the result of Zahra Akbari’s general medical dissertation with research code number of 970252.

References

- Yamaguchi JT, Garcia RM, Cloney MB, Dahdaleh NS (2018) Impact of resident participation on outcomes following lumbar fusion: An analysis of 5655 patients from the ACS-NSQIP database. J Clin Neurosci 56: 131-136.

- Phan K, Phan P, Stratton A, Kingwell S, Hoda M, et al. (2019) Impact of resident involvement on cervical and lumbar spine surgery outcomes. Spine J19(12): 1905-1910.

- Pugely AJ, Gao Y, Martin CT, Callagh JJ, Weinstein SL, et al. (2014) The effect of resident participation on short-term outcomes after orthopaedic surgery. Clin OrthopRelat Res472(7): 2290-300.

- Lee NJ, Kothari P, Kim C, Leven DM, Skovrlj B, et al. (2018) The Impact of Resident Involvement in Elective Posterior Cervical Fusion. Spine 43(5): 316-323.

- Gelalis ID, Papanastasiou EI, Pakos EE, Ploumis A, Papadopoulos D, et al. (2019) Clinical outcomes after lumbar spine microdiscectomy: a 5-year follow-up prospective study in 100 patients. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol29(2): 321-327.

- Ghoneim MM, O'Hara MW (2016) Depression and postoperative complications: an overview. BMC Surg16: 5.

- Yao Y, Liu H, Zhang H, Wang H, Zhang C, et al (2017) Risk Factors for Recurrent Herniation After Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy. World Neurosurg 100: 1-6.

- Fjeld OR, Grøvle L, Helgeland J, Småstuen MC, SolbergTK, et al. (2019)Complications, reoperations, readmissions, and length of hospital stay in 34 639 surgical cases of lumbar disc herniation. Bone Joint J101-B(4): 470-477.

- Reed MD, Van Nostran W (2014) Assessing pain intensity with the visual analog scale: a plea for uniformity. J Clin Pharmacol54(3): 241-244.

- Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB (2000) The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine 25(22): 2940-2952.

- Mousavi SJ, Parnianpour M, Mehdian H, Montazeri A, Mobini B (2006) The Oswestry Disability Index, the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale: translation and validation studies of the Iranian versions. Spine, 31(14): E454-459.

- Macnab I (1971) Negative disc exploration: an analysis of the cause of nerve root involvement in sixty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am53(5): 891-903.

- Shriver MF, Xie JJ, Tye EY, Rosenbaum BP,Kshettry VR, et al. (2015) Lumbar microdiscectomy complication rates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Focus39(4): E6.

- Kanno H, Aizawa T, Hahimoto K, Itoi E (2019) Minimally invasive discectomy for lumbar disc herniation: current concepts, surgical techniques, and outcomes. Int Orthop43(4): 917-922.

- Omidi-Kashani F, Baradaran A, Golhasani-Keshtan F, Rahimi MD, Hasankhani EG (2016) Identifying predisposing factors for recurrence after successful surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation. Med J DY Patil Univ9(4): 469-473.

- DeBerard MS, Wheeler AJ, Gundy JM, Stein DM, Colledge AL (2011) Presurgical biopsychological variables predict medical, compensation, and aggregate costs of lumbar discectomy in Utah workers' compensation patients. Spine J11(5): 395-401.

- Chua TC, Mittal A, Nahm C, Hugh TJ, Arena J (2018)Pancreatoduodenectomy in a public versus private teaching hospital is comparable with some minor variations. ANZ J Surg88(6): E526-E531.

- Spaziani E, Di Filippo AR, Orelli S, Tintisona O, Girolamo VD (2017) The influence of residents in the outcome of elective laparoscopic surgery: a prospective study comparing a teaching hospital and a private community hospital in Italy. Clin Ter168(1): e28-e32.

- Unger JB, Caldito G, Sams J, Perrone JF, Byrd E (2002) Satisfaction with hysterectomy: low-income underinsured teaching hospital patients versus insured patients at a private hospital. Am J ObstetGynecol187(6): 1528-1532.