Cytological Diagnosis of Giant Cell Lesions in Infants-A Red Herring

Neema Tiwari1, Devajit Nath1*, Jyotsna Madan1, Savitri Singh1, Manish Girhotra2 and Abhishek Gupta2

1Department of Pathology, Super Speciality Pediatric Hospital and Post graduate Teaching Institute, Noida, India

2Department of ENT, Super Speciality Pediatric Hospital and Post graduate Teaching Institute, Noida, India

Submission:June 04, 2020; Published: July 10, 2020

*Corresponding author: Dr Devajit Nath, Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, Super Speciality Pediatric Hospital and Post graduate teaching Institute, Noida, India

How to cite this article: Neema T, Devajit N, Jyotsna M, Savitri S, Manish G, et al. Cytological Diagnosis of Giant Cell Lesions in Infants-A Red Herring. Ortho & Rheum Open Access J. 2020; 16(4): 555942. DOI: 10.19080/OROAJ.2020.16.555942

Abstract

Introduction: Head and neck swellings and nodules are commonly seen in the pediatric population with most of the lesions falling in the benign neoplasm category. Auricular tumors are relatively rare with most common swellings being infective or congenital. Giant cell mesenchymal tumors are an entire spectrum of tumors and they are rarely been reported on the pinna. Pilomatricoma is an unusual, relatively rare, slowly growing benign tumor of the skin appendages. The histomorphological features of pilomatricoma are characteristic, but the cytological diagnosis remains problematic because of mimickers with other small round blue cell tumors. Here we present a case of pilomatricoma which presented with diagnostic pitfall in cytological diagnosis

Case:A two-and-a-half-month-old female child presented with a slowly growing fleshy pinkish whitish firm swelling at the medial aspect of the right pinna for last 1 month. The swelling was painless and was not associated with other symptoms like fever, discharge from the lesion or external ear, any hearing loss or ulceration and destruction of the surrounding area. FNAC was done and scant blood mixed material aspirated. Smears showed presence of few clusters of mononuclear round blue cells with few spindled cells with fair number of giant cells admixed with very scant amorphous pink material on a hemorrhagic background. A diagnosis of giant cell mesenchymal lesion was made, and histopathology was advised. Histopathological examination revealed presence of giant cells against intradermal keratin admixed with ghost cells and basaloid to mononuclear intermediate cells. A diagnosis of pilomatricoma was made.

Conclusion:The case highlights how giant cells on cytology may masquerade as giant cell mesenchymal lesion in a classic case of pilomatricoma from an uncommon location like pinna in a pediatric patient and may act as a diagnostic pitfall for the cytologist

Keywords: Pilomatricoma; Herring; Giant cell; Mesenchymal

Introduction

Cutaneous nodules in the head and neck region in infants fall under a wide spectrum of differential diagnosis. Swellings in the Head and neck region are very common in pediatric population which include auricular region nodules and swellings as well. Auricular sinuses and cysts are common developmental anomalies in infants. Auricular nodules are relatively rare with the most common swellings being infective or congenital. Giant cell rich mesenchymal tumors are an entire spectrum of tumors and they are rarely been reported on the pinna. Some rare cases of chondroblastoma pinna and extraosseous giant cell tumor have been reported, however chondrosarcomas and metastatic lesions are extremely rare in the pediatric age group [1,2].

The role of Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) as a diagnostic tool is limited for the cutaneous lesions as most of the cutaneous nodules are either surgically excised or biopsied for tissue diagnosis. Amongst the cutaneous nodules, pilomatricoma although a rare entity is common in head and neck region. It is also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe and is a skin appendage tumor of hair matrix origin which usually occurs on face, head and neck region and upper extremities. It presents as a solitary, slow growing dermal or subcutaneous nodule and is rarely clinically diagnosed [3].

The Diagnostic Challenge

The histological diagnosis of pilomatricoma is relatively straight forward however diagnosis on aspiration cytology may not be the same. The diagnosis is especially problematic when the lesions are focally sampled, with predominance of one component in an aspirate over the others [4]. There have been quite a few reports of misdiagnosis of pilomatricoma on aspiration cytology as other benign as well as malignant lesions resulting in over diagnosis of malignancy [5]. An accurate diagnosis of this benign lesion on cytology is necessary, considering that excision is curative. Although pilomatricomas are common in the head and neck region yet medial aspect of pinna is a very rare site of occurrence for this benign lesion.

We present a case of a two-and-a-half-month-old female infant who presented with lesion at the medial aspect of pinna for 1 month. On FNAC a diagnosis of giant cell rich mesenchymal lesion was made, and an excision was advised. On histopathology a diagnosis of pilomatricoma was made. The rare site of occurrence at the medial aspect of pinna, the very young age of patient and the diagnostic pitfalls and challenges in fine needle aspiration cytology merit an interesting case discussion.

Case Report

We present a case of a two-and-a-half-month-old female child who presented with complaints of a fleshy, pinkish white, firm swelling at the medial aspect of the right pinna since 1 month. The swelling was painless, slowly progressive with no other accompanying symptoms like fever, discharge from the lesion or external ear, any hearing loss, ulceration, or destruction of the surrounding area. All other investigating parameters were within the normal limits. The swelling was approximately 2.5x2.0 cm in size (Figure 1). No significant family history, past history or history of trauma was found. An FNA was done using a 22G needle. Two passes from different sites were taken and scant blood mixed material was aspirated. Smears were air dried as well as fixed and stained with Romanowsky stains and examined.

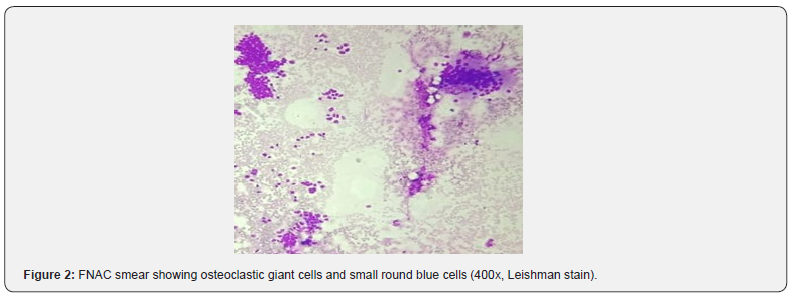

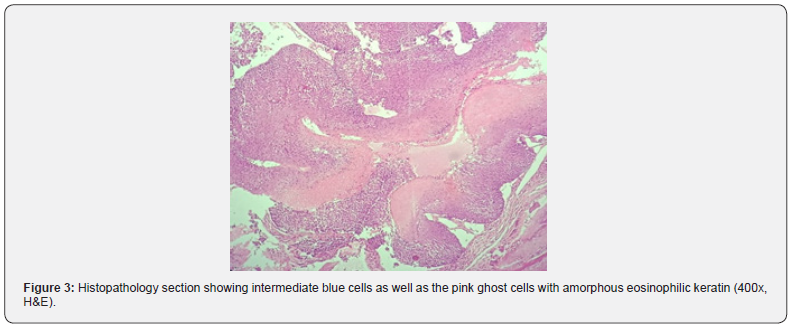

Smears showed presence of few clusters of mononuclear round blue cells with few spindled cells with fair number of giant cells admixed with very scant amorphous pink material on a hemorrhagic background (Figure 2). A diagnosis of giant cell rich mesenchymal lesion was made, and histopathology was advised. Histopathological examination revealed presence of giant cells against intradermal keratin admixed with ghost cells and basaloid to mononuclear intermediate cells (Figure 3). A diagnosis of pilomatricoma was made. The child is well and on regular follow up.

Discussion

Pilomatricoma, a benign slow growing skin adnexal neoplasm, seen in children and young adults, with a slight female preponderance [3-5]. It is also reported in the elderly individuals. Familial occurrence is rare however few cases have been reported in association with myasthenia gravis and Gardner syndrome [6]. Common sites of pilomatricoma are the hair-bearing areas mainly the head, neck, and upper extremities [3]. Generally, pilomatricoma is located in deep dermal or subcutaneous tissue [3]. It has a differentiation towards matrix and inner sheath of normal hair follicle and cortex. Clinically it presents as a solitary slow growing dermal or subcutaneous nodule. These lesions are often clinically misdiagnosed as small round blue cell tumors, basal cell carcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, sebaceous cysts, or dermoid cysts. According to one study 74% of pilomatricomas are incorrectly diagnosed pre-operatively [7] which causes unnecessary investigations and extensive surgery.

Cytologically it has a combination of two salient features: ‘ghost cells’ and basaloid cell clusters. These ‘ghost cells’ are pathognomonic and are identified by a central pale nuclear zone and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. The basaloid cells frequently have prominent nucleoli corresponding to matrical cells in histological section and should not be over diagnosed [8,9]. Other accompanying features are refractile keratin clumps, foreign body giant cell reaction and calcium deposits. However, ghost cells might not be present every time in an aspirate and that is probably due to difficulty in detaching these cells during aspiration [10]. Pilomatricomas may be confused with malignancies on FNA specially due to presence of atypical basaloid cells, together with marked nuclear pleomorphism and atypical mitosis. Pilomatricoma with atypia on cytology specially occurring in elderly population should raise the suspicion of pilomatrical carcinoma recurrence [11]. In our case, patients age, clinical history, indolent course of development of nodule and lack of significant pleomorphism cytologically, resisted us to definitely conclude the possibility of malignancy and surgical biopsy was advised.

The cytological diagnosis of pilomatricoma is particularly problematic with limited diagnostic material or when containing a predominance of one component over another [12]. In a case series it was seen that ‘ghost cells’ were absent in as many as 40% of FNA cytology of pilomatricoma [13]. Pilomatricoma were diagnosed correctly on 21% of FNA cytology while 25% of cases were misdiagnosed as malignant on cytology smears. This shows the importance of thorough sampling to obtain adequate diagnostic material in an aspirate. Some authors also suggest the routine use of cell block to minimize diagnostic errors because ‘ghost cells’ are more readily seen in cell block sections [14,15].

Grossly it is a lobulated mass with whitish flaky keratin like material on cut surface. Histologically, pilomatricoma is categorized into four sequential stages: early, fully developed, early regressive, and late regressive [11]. Early lesions are small and cystic, composed of basaloid aggregations (i.e. matrical and supramatrical cells) at the periphery, with abrupt trichilemmal keratinization towards the centre that forms anucleated ‘ghost cells. Fully developed lesions are larger than early-stage ones but exhibit similar histomorphology. In early regressive lesions, the bulk of the lesion primarily consists of cornified eosinophilic material containing ‘ghost cells. Only small foci of basaloid aggregations remain at the periphery. Lymphocytic infiltrates with multinucleated giant cells are often observed. late regressive stage shows totally ghost cells with complete absence of any other cell type. Variable degrees of calcification or ossification are frequently present [12]. Our case showed dermal cystic structure with flaky keratin in the cyst lumen and focal rupture of cyst wall resulting in foreign body giant cell reaction as well as presence of round to oval intermediate cells and ghost cells lining the cyst.

The differential diagnosis of pilomatricoma is broad cytologically and depends on the proportion of diagnostic components present. In cases where aspirates contain mainly sheets of anucleated and nucleated squamous cells, a pilomatricoma can be confused with an epidermal cyst or trichilemmal cyst. An important differentiating feature is that anucleated squamous cells of epidermal or trichilemmal cysts are singly dispersed, whereas those of ‘ghost cells’ in pilomatricoma tend to be in cohesive groups [16].

Skin appendageal tumours (e.g. cylindroma, eccrine spiradenoma or hidradenoma) can mimic pilomatricoma, especially when only basaloid cells are present in the aspirates. An important difference is that basaloid cells of skin appendageal tumours are usually arranged in cohesive clusters with a smooth contour, whereas those of pilomatricomas are often irregular, saw-toothed edged, monolayered loose cohesive sheets [17]. Unlike skin appendageal tumours, pilomatricomas also exhibit pathognomonic ‘ghost cells’, foreign body giant cell reaction and calcification. Foreign body giant cell reaction characterized by multinucleated giant cells is found in many dermatological conditions. The differential diagnosis ranges from non-neoplastic lesions (e.g. ruptured epidermal cysts, ruptured benign cysts and pilomatricomas) to neoplastic lesions (e.g. giant cell tumours and squamous cell carcinomas) [18]. Careful observation of the cell components is helpful in making an accurate diagnosis. A mistaken diagnosis of malignancy, such as squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma, has been reported in the literature [18-20]. ‘Ghost cells’ are often mistaken for tumour necrosis or disregarded as blood clots. The absence of atypical mitosis and significant nuclear atypia are useful features in excluding squamous cell carcinoma. Diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma can be excluded by the absence of tightly cohesive small, hyperchromatic basaloid cell clusters, with peripheral palisading and sharp borders. Generally, the nucleoli of basaloid cells in basal cell carcinoma are small to inconspicuous [10]. In contrast, they are more prominent in pilomatricoma.

In our case we got two populations of cells on cytology smears, small round blue cells and spindle cells admixed with fair number of giant cells which mimicked osteoclasts. Hence a diagnosis of giant cell rich mesenchymal lesion was made on the smears. Pilomatricoma was not considered in the differential diagnosis due to lack of ‘ghost cells’ in the aspirates, presence of fair number of giant cells, spindled to round blue cells and unusual location of the tumor at the medial aspect of the pinna. The lesion was mistaken for a possible mesenchymal neoplasm, with fair number of giant cells.

Conclusion

In conclusion, cytological diagnosis of pilomatricomas can be challenging. An accurate diagnosis can be made with careful observation of the presence of two key cytological features of these lesions: 1) pathognomonic ‘ghost cells’ or shadow cells and 2) basaloid cells, with prominent nucleoli. Presence of fair number of giant cells mimicking osteoclasts with only round blue cells and absence of ghost cells might act as red herring in the diagnosis of pilomatricoma like in our case.

References

- Lim HW, Im SA, Lim GY, Hyun Jin Park, Heejeong Lee, et al. (2007) Pilomatricomas in children: imaging characteristics with pathologic correlation. Pediatr Radiol 37(6): 549-55.

- Agarwal RP, Handler SD, Matthews MR, Carpentieri (2001) Pilomatrixoma of the head and neck in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 125: 510-515.

- Noguchi H, Hayashibara T, Ono T (1995) A statistical study of calcifying epithelioma, focusing on the sites of origin. J Dermatol 22(1): 24-27.

- Kwon D, Grekov K, Krishnan M, Dyleski R (2014) Characteristics of pilomatrixoma in children: a review of 137 patients. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 78(8): 1337-1341.

- Kumaran N, Azmy A, Carachi R, Raine PAM, Macfarlane JH, et al. (2006) Pilomatrixoma—accuracy of clinical diagnosis. J Pediatr Surg 41(10): 1755-1758.

- Pirouzmanesh A, Reinisch JF, Gonzalez-Gomez I, Smith EM, Meara JG (2003) Pilomatrixoma: a review of 346 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 112(7): 1784-1789.

- Greene R, McGuff H, Miller F (2004) Pilomatrixoma of the face: a benign skin appendage mimicking squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngology 130(4): 483-485.

- Malherbe A, Chenantais J (1880) Note sur l’epitheliome calcifie des glandes sebacees. Prog Med 8: 826-837.

- Moehlenbeck FW (1973) Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma): a statistical study. Arch Dermatol 108(4): 532-534.

- A Hernández-Núñez, L Nájera Botello, A Romero Maté , C Martínez-Sánchez , M Utrera Busquets, et al. (2014) Retrospective study of pilomatricoma: 261 tumors in 239 Patients. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr´aficas (English Ed) 105: 699-705.

- Graham JL, Merwin CF (1978) The tent sign of pilomatricoma. Cutis 22|(5): 577-580.

- Julian CG, Bowers PW, Cornwall F, Kingdom U (1998) A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 39(2 Pt 1): 191-195.

- Kajino Y, Yamaguchi A, Hashimoto N, Matsuura A, Sato N, et al. (2001) β-Catenin gene mutation in human hair follicle-related tumors. Pathol Int 51(7): 543-548.

- Chan E (2000) Pilomatricomas contain activating mutations in beta-catenin. J Am Acad Dermatol 43(4): 701-702.

- Hashimoto K, Magre L, Lever W (1967) Electron microscopic identification of viral particles in calcifying epithelioma induced polyoma virus. J Natl Cancer Inst 39(5): 977-992.

- Geh JL, Moss AL (1999) Multiple pilomatrixomata and myotonic dystrophy: a familial association. Br J Plast Surg 52(2): 143-145.

- Hashimoto K, Nelson RG, Lever WF (1966) Calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe. Histochemical and electron microscopic studies. J Invest Dermatol 46(4): 391-408.

- Amedee RG, Dhurandhar NR (2001) Fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Laryngoscope 111(9): 1551-1557.

- Domanski HA, Domanski AM (997) Cytology of pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) in fine needle aspirates. Acta Cytol 41(3): 771-777.

- Sanchez Sanchez C, Gimenez Bascunana A, Pastor Quirante FA, Socorro Montalbán Romero, Joaquin Campos Fernández et al. (1996) Mimics of pilomatrixomas in fine-needle aspirates. Diagn Cytopathol 14(1): 75-83.