Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of the 10-year Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) into Filipino

Pauline Melesse S del Rosario1*, Misael Jonathan A Ticman1 and Leo Daniel D Caro1,2

1Department of Orthopaedics, East Avenue Medical Center, Quezon City, Philippines

2Department of Orthopaedics, University of the Philippines, Philippine General Hospital, Philippines

Submission: December 15, 2019;Published: January 17, 2020

*Corresponding author: P M del Rosario, East Avenue Medical Center, Quezon City, Philippines

How to cite this article: Pauline Melesse S del Rosario, Misael Jonathan A Ticman, Leo Daniel D Caro.Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of the 10-year Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) into Filipino. Ortho & Rheum Open Access J. 2020; 15(5): 555921. DOI:10.19080/OROAJ.2020.15.555921

Abstract

Introduction: Screening tools for osteoporosis are relatively expensive and inaccessible to the general Filipino population. This study aims to develop a Filipino version of a validated measure, the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool, in order to facilitate improvement of fracture prevention care in the country.

Methods: The FRAX was translated and culturally adapted into a Filipino version using established forward and backward translation methods and was succeedingly tested for equivalence to the original. The final version was administered to 120 out-patients and was tested for reliability using BMD measurements of the distal radius.

Results: To be better understood and reliably answered by the Filipino population, several qualifiers were added to items such as previous fracture and rheumatoid arthritis. This was to account for the high incidence of high-energy trauma in the country, and the use of the same Filipino term for RA as with other arthritides, respectively.

Conclusion: The Filipino version of the FRAX appears to be an acceptable and reliable instrument, serving as a low-cost alternative to BMD and DXA scans which are generally inaccessible and unaffordable by majority of the population

Keywords: Filipino; FRAX; Fracture risk; Osteoporosis

Introduction

Osteoporosis remains a major global health problem, causing approximately 8.9 million fractures each year, 25-43% of which are fractures at the hip [1-4]. The combined lifetime risk of fractures of the hip, forearm and vertebrae secondary to osteoporosis is around 40%, roughly the equivalent of the lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease [5]. There is also an increase in the 5-year mortality rate of those with hip and vertebral fractures, which signal or begin a progressive decline in health [6]. Although surveillance, diagnosis and treatment protocols for osteoporosis have been developed and refined, the incidence of hip fractures continue to rise each year, which is unacceptable for a preventable morbidity [1]. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, ethnicity plays a significant role in the prevalence of fragility fractures [7,8]. In the Philippines, although classified as a country with low population risk for hip fractures, these still rank 4th in PhilHealth insurance claims, placing the annual economic burden of fractures higher than colon, prostate, or ovarian carcinoma [9,10].

This is in addition to the loss of productivity of at least one other family member who acts as the primary caregiver of the patient. Screening tools for osteoporosis such as dual energy x-ray absorptiometry is relatively expensive and not widely accessible to the general public, with only 21 machines available in the Philippines. Consequently, many patients who sustain a fragility fracture are not identified as high risk, and subsequently do not receive the appropriate treatment to prevent the said fracture [11,12]. More cost-effective alternatives are available scoring systems that determine the fracture risk of a patient, namely the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) [12-16].

This has been validated, and sometimes reconstructed, in several countries such as Japan and Tunisia, among others [17,18]. There are few local studies describing the prevalence of fractures and osteoporosis among individuals aged 50 and above in the Philippines, however , no national research studies to establish baseline risk for fracture in elderly Filipinos are available [9,19]. Once there is a cost-effective method of identifying and stratifying at-risk individuals, treatment may then be initiated in accordance with guidelines, improving fracture prevention care [19].

Materials and Methods

The fracture risk assessment tool contains 10 items measuring the patient’s age, height, weight and clinical risk factors such as previous fracture, parental hip fracture, smoking history, glucocorticoid therapy, rheumatoid arthritis, alcohol consumption, and secondary osteoporosis. The guidelines for translation by Beaton, et al. [20] were followed in the construction and cultural adaptation of the Filipino FRAX. Two independent forward translations of the English FRAX into Filipino were done by a physician and a naïve translator, both of whose mother tongue is Filipino. Any discrepancies between the two translations were discussed and resolved by the group. The synthesized Filipino version was subsequently converted back to English by two other translators who use English as their first language, both of whom were blinded to the original FRAX and naïve to the concepts being measured. A committee that included a general physician, an orthopedic surgeon and a linguist was then formed. Along with the translators and authors, they reviewed and verified all translations made in terms of semantics and conceptual equivalence to the English version. A consensus was reached on any discrepancies and a pre-final version was developed for field testing. The translation was straightforward for most items and response choices, except for items 4, 7 and 8, which required additions to ensure identification of target risk factors. In item 4 (previous fracture), “not due to high-energy trauma” was added to the question. In items 7 and 8 (glucocorticoid use and rheumatoid arthritis), qualifiers such as disease process, medications taken and diagnostic examinations were included, as some glucocorticoids are available as over-the-counter drugs in the Philippines. Also, the Filipino word for rheumatoid arthritis, ‘rayuma,’ is also often loosely used for other forms of arthritis.

The pre-final Filipino FRAX was tested on a convenience sample of 58 men and women aged 50-90 years old admitted by the orthopedic surgery department of a tertiary government hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The questionnaire was administered, and participants were probed about clarifications needed on any of the items. All odd numbered patients were requested to answer the Filipino FRAX again 10 days after admission, and test-retest reliability was tested. The final version was field tested on 120 male and female subjects aged 50-90 years old, and BMD measurements of the distal radius were simultaneously measured and recorded. Clinical risk factors and BMI were then used to determine 10-year fracture risk using charts provided by the FRAX. These were then correlated to BMD T-scores to test for validity of the final version.

Results

Pre-Final Version

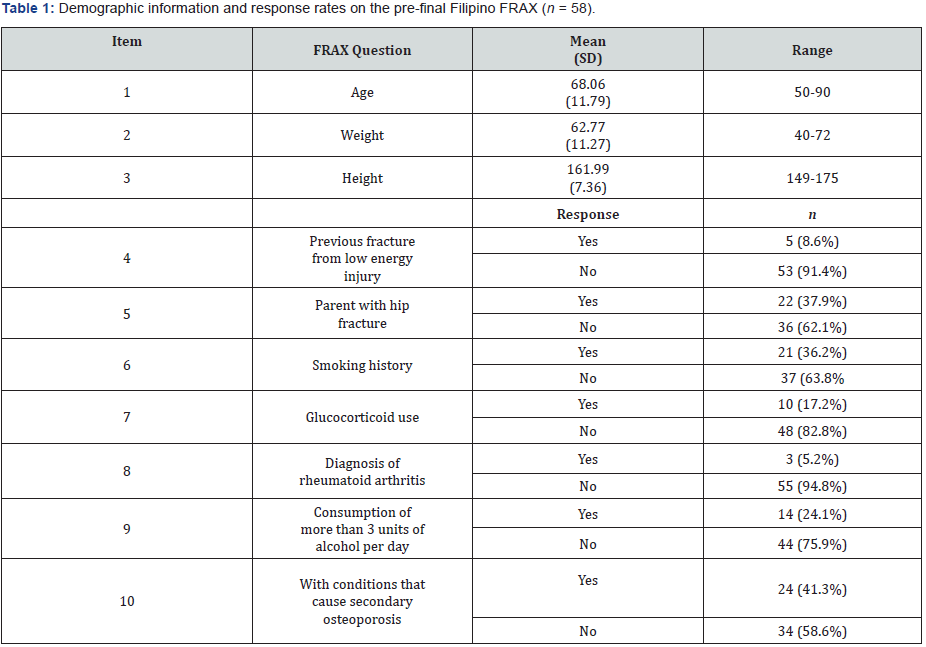

The pre-final version was field tested on 58 in-patients, 31 (53.4%) of which were female and 27 (46.5%) were male, with a mean age of 68.06. Most questions were understood by the respondents. Nine patients required further explanation of galanggalangan or wrist, while three others inquired about other glucocorticoids which were not given as an example on the questionnaire. Odd serial numbered patients were requested to answer the questionnaire on the 10th day of admission. Test retest reliability (Pearson r) was 0.98 and 0.99 for weight and height, respectively. Repeatability was perfect for all items except for diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (r = 0.91). Patient demographics and responses on the pre-final FRAX is summarized in Table 1.

Final Filipino FRAX

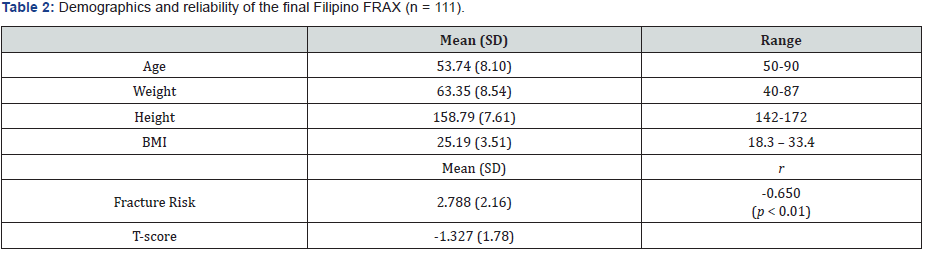

The final version of the Filipino FRAX was administered to 120 outpatients, 78 (65%) of which were female and 42 (35%) were male, aged 50-90 (55.5 ± 6.34). There was a total of 9 dropouts due to questionnaires being deemed invalid for being incompletely answered. Pearson r for 10-year 3 fracture risk and BMD t-scores was -0.650 (p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Discussion

Measures have been translated, as well as culturally adapted, across countries in order to maintain validity and equivalence between the original and translated version at a conceptual level. This is especially true if the questionnaire is to be used in a different country and language, as is in our case [20]. This study developed a translated and culturally adapted version of the FRAX that can be used in Filipino-speaking populations. The most significant changes to the FRAX were additions of qualifiers to items such as previous fracture and rheumatoid arthritis, to ensure that they measure the target risk factors. This is due to the high prevalence of high energy trauma and the use of the Filipino word rayuma to pertain to other forms of arthritis. This study, however, has some limitations, including a sample gathered by convenience at a tertiary public hospital.

Patients who do not have the means to seek consult at a tertiary centre may also have less familiarity with medical terms used in the questionnaire. Also, for some patients, the questionnaire was interviewer-administered, due to the inability to read and write and low educational status of several subjects. Given that the Filipino FRAX has significant reliability in comparison to standards of measurement (e.g. BMD) in screening for osteoporosis and fracture risk, the authors recommend that this tool be used by general practitioners as well as specialists in their daily patient care to allow early intervention in the prevention of fractures. It appears to be an acceptable and reliable instrument which may be used as a low-cost alternative to standards of measurement in areas where the former is inaccessible and unaffordable by the general population. This study is the first translation of the FRAX in Filipino. Further studies are encouraged to validate its results and to determine its ability to prognosticate fractures and to quantify fracture risk. Furthermore, the tool may be translated to other Philippine dialects to benefit a larger population with different ethnicities. Larger, epidemiological studies are recommended to obtain data on fracture risk in the Filipino population.

Conclusion

Diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis prior to a fracture is currently of low priority, despite a wide range of therapeutic options that are available. This risk assessment tool serves to identify individuals at high risk for eventually developing a fragility fracture, and in turn influence clinical decision-making, especially in regions of the country wherein bone densitometry is not available. Fracture prevention intervention should be deemed as necessary as fracture management, in order to lower fragility fracture incidence and cost in the country.

Conflict of Interest

Pauline Melisse del Rosario and Misael Jonathan Ticman declare that they have no conflict of interest. Leo Daniel Caro discloses that he is a speaker for Unilab’s product Alendra (Alendronic Acid). However, no grants or research support was received from the company, and no commercial benefits will be conferred upon the authors.

References

- Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ (1992) Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int 2(6): 285-289.

- Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17(12): 1726-1733.

- Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Jonsson B, De Laet C, et al. (2000) The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Osteoporos Int 12(5): 417-427.

- Oden A, Dawson A, Dere W, Johnell O, Jonsson B, et al. (1998) Lifetime risk of hip fractures is underestimated. Osteoporos Int 8(6): 599-603.

- Kanis JA (2002) Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet 359(9321): 1929.

- Ioannidis G, Papaioannou A, Hopman WM, Akhtar-Danesh N, Anastassiades T, et al. (2009) Relation between fractures and mortality: Results from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. CMAJ 181(5): 265-271.

- Davis JW, Novotny R, Wasnich RD, Ross PD (1999) Ethnic, anthropometric, and lifestyle associations with regional variations in peak bone mass. Calcif Tissue Int 65(2): 100-105.

- Lau EMC, Suriwongpaisal P, Lee JK, Das De S, Festin MR, et al. (2001) Risk factors for hip fracture in Asian men and women: The Asian Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res 16(3): 572-580.

- Li-Yu J (2007) Prevalence of osteoporosis and fractures among Filipino adults. Phil J Int Med 45: 57-63.

- Wu CH, McCloskey EV, Lee JK, Itabashi A, Prince R, et al. (2014) Consensus of official position of IOF/ISCD FRAX initiatives in Asia-Pacific region. J Clin Densitom 17(1): 150-155.

- Nguyen TV, Center JR, Eisman JA (2004) Osteoporosis: underrated, underdiagnosed and undertreated. Med J Aust 180(S5): S18-22.

- Leslie WD, Morin S, Lix LM, Johansson H, Oden A, et al. (2012) Fracture risk assessment without bone density measurement in routine clinical practice. Osteoporos Int 23(1): 75-85.

- Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Strom O, et al. (2010) Development and use of FRAX® in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 21(S2): 407-413.

- Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, De Laet C, Johansson H, Johnell O, et al. (2005) Assessment of fracture risk. Osteoporos Int 16(6): 591-589.

- International Osteoporosis Foundation, International Society for Clinical Densitometry. International Osteoporosis Foundation, International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) official positions on FRAX.

- Watts NB (2011) The Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX®): Applications in clinical practice. J Womens Health 20(4): 525–531.

- Fujiwara S, Nakamura T, Orimo H, Hosoi T, Gorai I, et al. (2008) Development and application of a Japanese model of the WHO fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX). Osteoporos Int 19(4): 429-435.

- Zrour-Hassen S, Jguirim M, Guezguez M, Mnif H, Younes M, et al. (2011) The fracture risk assessment tool (FRAXTM), where are we in Tunisia? Tunis Med 89(2): 136-141.

- Li-Yu J, Perez EC, Cañete A, Bonifacio L, Llamado LQ, et al. (2011) Consensus statements on osteoporosis diagnosis, prevention, and management in the Philippines. Int J Rheum Dis 14(3): 223-238.

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB et al. (2000) Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 25(24): 3186–3191.