Polydioxansulfate (PDS) Cerclage Technique for the 1- Treatment of Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocations

Alia Mahmood, Sanil H Ajwani*, Fizan Younis, Saeed Taqvi and Late Leo Jacobs

Trauma and Orthopaedics Department, The Royal Oldham Hospital, England

Submission: October 28, 2017; Published: November 14, 2017

*Corresponding author: Sanil Ajwani, Trauma and Orthopaedics Department, The Royal Blackburn Hospital, East Lancashire NHS Trust, Haslingden Road, Blackburn, BB2 3HH, Lancashire, England, Tel: 07891891899; Email: sanilajwani@doctors.org.uk

How to cite this article: Mahmood A, Ajwani S H, Younis F, Jacobs L. Polydioxansulfate (PDS) Cerclage Technique for the Treatment of Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocations. Ortho & Rheum Open Access 2017;9(2): 555756. DOI: 10.19080/OROAJ.2017.09.555756.

Abstract

Background: The optimal operative treatment of acromioclavicular joint dislocations is yet to be established. We present our experience of open reduction and cerclage using a Polydioxansulfate (PDS) cordelette. We aimed to assess the outcomes of surgery in the patients treated with the PDS cerclage technique.

Materials and Methods: We retrospectively reviewed 24 patients treated over a 15-year period at our institution. Patients’ self-reported shoulder function, pain scores and overall satisfaction with the procedure were determined post-operatively.

Results: Twenty-four patients with a mean age of 39.2 years were reviewed with mean follow up of 5.4 years. Stratification into Rockwood grades identified 13 grade III, 7 grade IV and 4 grade V injuries. The mean Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) was 39.5/48, the mean Pain Score was 7.4/10 (1 extreme pain and 10 no pain) and the mean Satisfaction Score was 8.2/10 (1 dissatisfied and 10 extremely satisfied). A clinically significant improvement in shoulder function correlated with improvement in patient reported pain scores p=0.03. We explored the differences between outcomes according to Rockwood grade and found no statistically significant difference in OSS (p=0.3937), Pain Score (p=0.906) and Satisfaction Score (p=0.8916). Three patients in this series required revision surgery.

Conclusion: This study shows PDS cerclage is an effective way of treating acromioclavicular joint dislocations.

Keywords: Acromioclavicular Joint; Dislocation; Trauma; Polydioxansulfate

Abbreviations: ACJ: Acromioclavicular joint; CC: Coracoclavicular; PDS: polydioxane sulphate; OSS: Oxford Shoulder Score

Introduction

Acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) dislocations are common and represent up to 20% of all shoulder injuries [1,2]. The mechanism is generally a fall on to the point of the shoulder with the arm adducted, leading to inferior displacement of the acromion [3]. This explains the preponderance of these injuries in athletes. The Rockwood classification grades these injuries into six groups based on severity of injury [4]. Grade I and II injuries are treated conservatively with surgical intervention reserved for grade IV-VI injuries [5]. The optimal treatment for grade III injuries remains controversial [6,7]. This is despite the reported success of nonoperative treatment in the literature and is thought to be due to the dissatisfaction seen in a small subsection where residual pain and weakness is problematic [1]. This is often the case in manual workers and athletes. Surgical intervention for ACJ dislocations has evolved substantially since Cooper performed the first operation for an ACJ dislocation in 1861 [8]. A multitude of surgical interventions have been proposed since, however no ideal surgical solution has been determined for ACJ dislocations [6-12]. Novel less invasive techniques are gaining favour with specific attention to biological repair [3,13]. Traditional treatment techniques have fallen into a number of categories.

These range from excision of the distal end of clavicle or primary fixation of the ACJ to secondary fixation using the coracoid or dynamic stabilization. [3,7,14] Each alternative technique however generates its own disadvantages and complications. These include pin migration, bony defects and joint instability [14,15]. Reconstruction of the Coracoclavicular (CC) ligament complex has long been recommended for ACJ dislocations. However CC cerclage techniques [16] have a theoretical shortcoming of mal-reduction and anterior subluxation in experimental settings. In addition, the use of non-resorbable materials is thought to provoke osteolysis and stress fractures [7,14,17]. We present a simple and effective technique of open reduction of the ACJ followed by a cerclage technique using a polydioxane sulphate (PDS) cordalette. The cordalette is passed around the coracoid and lateral clavicle to simulate the CC ligaments. This technique obviates the need for removal of an implant [18]. Previous studies using PDS cerclage techniques have displayed promising results with reduced number of complications in comparison to more traditional approaches [17-20]. This retrospective review analyses the mid to long-term outcomes for patients treated with this technique at our institute over a 15 year period.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective review of 24 consecutive patients who underwent ACJ reconstruction with the PDS cerclage technique from November 1994 to August 2010. All patients who underwent ACJ reconstruction with the PDS cerclage technique as the primary procedure were included in the study. Patients who had previous surgery performed on the ipsilateral ACJ or had sustained associated injuries on the same limb were excluded from the study. Our initial search identified 44 patients who may have had surgery for ACJ dislocations. Of these patients 8 were excluded following a review of their case notes as 1 was a revision procedure and the remaining 7 had an alternative diagnosis such as a clavicle fracture. We reviewed the case notes of the remaining cohort of 36 patients. This was then followed up with telephone review. Those that did not respond were then sent a maximum of three consecutive postal questionnaires.

We were able to trace 24 patients who completed the follow up questionnaires. The remainder could not be traced despite repeated phone calls and postal questionnaires being sent. This is unfortunately a frequent problem with long-term retrospective studies. Clinical outcome measures recorded post-operatively included the Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS), Pain scores and a satisfaction score. Pain and satisfaction scores were subjectively quantified between 0 and 10 (10 being pain free/most satisfied and 0 being very painful/extremely dissatisfied respectively). The satisfaction score had 5 components with each component contributing 2 points to the eventual satisfaction score. The components included: a score for cosmetic appearance and residual deformity, range of movement in the shoulder, strength of the shoulder, ability to return to work and sports and whether the patient would have the operation again. There was no radiological follow up performed.

Operative Technique

A "bra-strap" incision is made from just posterior to the ACJ to the coracoid. The clavicle and ACJ are then identified. A 10mm segment of the distal end of the clavicle is usually excised to avoid any post-operative impingement. The PDS cordalette is then passed around the coracoid taking care to protect the neurovascular structures medially. A 2.5mm drill bit is then used to drill a hole anterior to posterior through the lateral end of the clavicle. This is approximately 5mm medial and parallel to the ACJ. One limb of the cordalette is the passed anterior to posterior through the drill hole and the second posterior to anterior. Having done this the two ends of the cord are pulled to reduce the ACJ. The assistant then holds the ACJ in the reduced position whilst a knot is then tied over the top of the clavicle. The wound is then closed in layers. Postoperative care includes a broad arm sling for 2 weeks with elbow and wrist exercises commencing straight away. Pendular exercises for the shoulder commence from 48hrs post-operatively. Range of motion exercises commence at 2 weeks and strengthening exercises from 6 weeks post-operatively.

Statistical Analysis

Data was collated in Microsoft Excel 2010 and analysed using Stats direct statistical software version 2.8.0. The dataset was tested for non-normality using a Shapiro-Wilk test. When the data was found to be from a non-parametric distribution it was analysed using a Mann Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test. The data was also evaluated to look at correlation between shoulder function and pain scores. Correlation testing of the data was conducted and analysed using Kendall's tau correlation coefficient.

Results

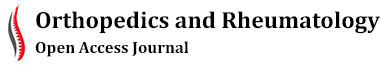

The final cohort of 24 patients comprised of 17 males and 7 females. The mean age was 39.2 years (range 17-80 years). The cohort was stratified by Rockwood grade and we found that there were 13 (54%) grade III, 7 (29%) grade IV and 4 (17%) grade V injuries. The mean follow up was 5.4 years (range 0.6-14.3 years) and the mean interval from injury to surgery was 122 days (range 2 days-25 months). The vast majority (79%, 19 patients) of patients who underwent surgery had an ASA grade of 1. The most common mechanism of injury was a mechanical fall (13 patients), followed by road traffic accidents (7 patients) and sports injuries (4 patients). A summary of the demographics of patients is compiled in Table 1. The OSS is a subjective evaluation of shoulder function and is graded from 0-48 with a higher number reflecting superior function. The mean post-operative OSS in our cohort was 41.9 (95% CI 38.7 - 45.1) demonstrating good post-operative function.

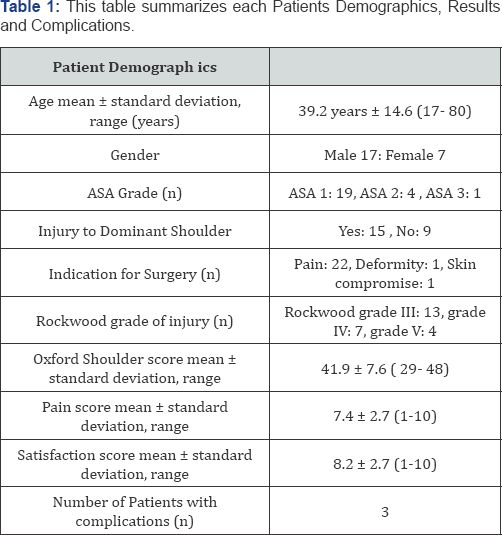

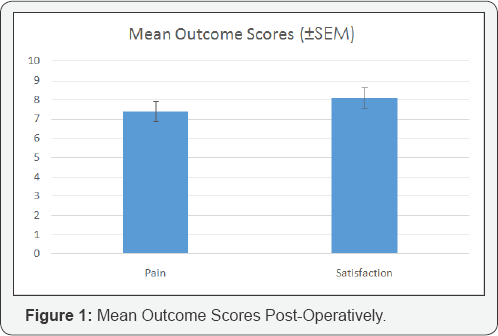

The mean pain score was 7.4 (95% CI 6.3-8.5) and mean satisfaction score was 8.2 post-operatively (95% CI 7.0-9.3). This reflects a very high rate of satisfaction with the procedure with little residual pain (Figure 1). Seven patients reported no pain at all and 13 patients were completely satisfied post-operatively. All patients returned to their previous occupations despite the majority of injuries (62.5%, 15 patients) affecting the patient’s dominant side. A Kendall correlation coefficient demonstrated that the improved shoulder function also correlated well to an improvement in pain score p=0.03 (Figure 2). We stratified the outcomes based on Rockwood grade. This was in order to assess the impact of injury severity on final outcome. We found that there was no statistically significant difference in OSS (p=0.3937), Pain Score (p=0.906) or Satisfaction Score (p=0.8916) based on Rockwood grade using a Kruskal-Wallis test and confirmed no difference in groups using a Mann Whitney U test. This suggests that the severity of the original injury did not adversely affect the outcome following surgery. We then assessed the outcomes based on the chronicity of the injury. We defined a chronic injury as one where greater than 3 months had elapsed between injury and surgery. Seven out of the 24 patients fell into this category.

We found that this group had a mean OSS of 40.4, mean satisfaction score of 8.3 and a mean pain score of 7.9. These scores are comparable to the acute injury group outlining the potential benefits of this technique in both the acute and chronic settings. There were three re-operations. One patient suffered a stress fracture and required excision of the lateral end of clavicle. He made a full recovery and was asymptomatic at final review. The remaining two patients had surgery under different surgeons for ongoing pain. The first of these had a sub acromial decompression resulting in pain relief and we are unaware of the nature of the surgery of the second patient who also went on to make a complete recovery.

Discussion

In 1861 Cooper described the first surgical technique for ACJ dislocations leading to an array of surgical techniques thereafter [8]. The traditional approaches that were once deemed innovative are now described as out-dated and invasive [21]. The Weaver Dunn procedure involving the transfer of the coracoacromial ligament to the distal clavicle was long considered the treatment of choice [22]. However concerns related to residual subluxation, implant migration and breakage and the inferior ultimate load of the transferred coracoacromial ligament compared to the intact CC ligament complex have paved the way for contemporary alternatives [22-26]. This study aimed to evaluate the technique of PDS cerclage for the treatment of ACJ dislocations. The results from this study demonstrate good function, pain relief and satisfaction post-operatively regardless of the severity of the injury. We also have shown the technique to have a small number of complications.

This is in keeping with other studies where the efficacy of the PDS cerclage for ACJ dislocations has been demonstrated [14,17,18,20]. The PDS cerclage technique is relatively inexpensive and easy to perform leaving a small surgical scar of approximately 3-4 centimetres. It confers stability in both the superior-inferior and anteroposterior planes reducing any pain secondary to anteroposterior instability of the clavicle [7]. In addition it obviates the risks involved with metal implants such as migration and the need for implant removal [8,27]. This study has demonstrated this technique confers improvements in shoulder function with good correlation to improvement in pain scores. This technique seems to offer lasting relief in the medium to long term. The PDS cerclage technique focuses primarily on facilitating the healing of the ruptured CC ligament. It does this by holding the ACJ reduced whilst this process of healing takes place. This fixation technique does rely on the ability of the CC ligament to heal to its normal length with sufficient tensile strength.

Failure of the CC ligament to heal to the appropriate length or tensile strength could lead to a recurrence of the deformity given the absorbable nature of the cordalette [28]. However, this was not an issue within our study or other studies that have used PDS cerclage technique as a treatment option for ACJ dislocations [14,18-20]. The recognised complications of the procedure include superior migration of the clavicle, osteoarthritis of the ACJ, coracoclavicular calcification, superficial infection, deep infection and re-dislocations. Our study noted three re-operations. These included a patient who had an excision of the lateral end of the clavicle secondary to a stress fracture, another patient had a subacromial decompression for on-going pain and the final patient had a revision procedure under another surgeon for unknown reasons. Within our cohort, there were no acute or chronic infections or re-dislocations.

We accept that this was a retrospective study with small patient numbers and there are inevitable limitations with this type of review. In addition to this there were no final clinical or radiological outcomes assessed which may be regarded as a shortcoming. However, we believe that the combination of the Oxford Shoulder Score, satisfaction score and pain score is a reasonable reflection of the patient s shoulder function. We did not perform a final radiological follow up. This was largely due to the finding in preceding studies that radiological appearance did not correlate well with functional outcomes [7,14]. Despite this, we believe that we have managed to demonstrate the efficacy of the PDS cerclage technique in the treatment of ACJ dislocations over a prolonged period.

Conclusion

The Polydioxansulfate (PDS) cerclage technique for the treatment of acromioclavicular joint dislocations presents a simple, reliable and reproducible procedure with good postoperative outcomes.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Fraser Moodie JA, Shortt NL, Robinson CM (2008) Injuries to the acromioclavicular joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br 90(6): 697-707.

- Kocher MS, Dupre MM, Feagin JA (1998) Shoulder injuries from alpine skiing and snowboarding. Aetiology, treatment and prevention. Sports Med 25(3): 201-211.

- Rushton PR, Gray JM, Cresswell T (2010) A simple and safe technique for reconstruction of the acromioclavicular joint. Int J Shoulder Surg 4(1): 15-17.

- Rockwood CJ, Williams G, Young D (1998) Disorders of the acromioclavicular joint. In Rockwood CJ, Matsen F, The Shoulder. Saunders, Philadelphia, USA, 1: 483-553.

- Basyoni Y E GA, Aboul Saad M (2010) Acromioclavicular joint reconstruction using anchor sutures: surgical technique and preliminary results. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica 76(3): 307-311.

- Fraschini G, Ciampi P, Scotti C, Ballis R, Peretti GM (2010) Surgical treatment of chronic acromioclavicular dislocation: comparison between two surgical procedures for anatomic reconstruction. Injury 41(11): 1103-1106.

- Ladermann A, Grosclaude M, Lubbeke A, Christofilopoulos P, Stern R, et al. (2011) Acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular cerclage reconstruction for acute acromioclavicular joint dislocations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 20(3): 401-408.

- Cooper ES (1861) New method of treating long standing dislocations of the scapula-clavicular articulation. Am J Med Sci 1: 389-392.

- Jiang C, Wang M, Rong G (2008) Proximally based conjoined tendon transfer for coracoclavicular reconstruction in the treatment of acromioclavicular dislocation. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90: 299-308.

- Salzmann GM, Walz L, Buchmann S, Glabgly P, Venjakob A, Imhoff AB (2010) Arthroscopically assisted 2-bundle anatomical reduction of acute acromioclavicular joint separations. Am J Sports Med 38(6): 1179-1187.

- Thiel E, Mutnal A, Gilot GJ (2011) Surgical outcome following arthroscopic fixation of acromioclavicular joint disruption with the tightrope device. Orthopedics 34 (7): e267-e274.

- Weaver JK, Dunn HK (1972) Treatment of acromioclavicular injuries, especially complete acromioclavicular separation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 54(6): 1187-1194.

- Mazzocca AD, Santangelo SA, Johnson ST, Rios CG, Dumonski ML, et al. (2006) A biomechanical evaluation of an anatomical coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 34(2): 236-246.

- Greiner S, Braunsdorf J, Perka C, Herrmann S, Scheffler S (2009) Mid to long-term results of open acromioclavicular-joint reconstruction using polydioxansulfate cerclage augmentation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 129(6): 735-740.

- Sethi GK, Scott SM (1976) Subclavian artery laceration due to migration of a Hagie pin. Surgery 80(5): 644-646.

- Salzmann GM, Walz L, Schoettle PB, Imhoff AB (2008) Arthroscopic anatomical reconstruction of the acromioclavicular joint. Acta Orthop Belg 74(3): 397-400.

- Baker JE, Nicandri GT, Young DC, Owen JR, Wayne JS (2003) A cadaveric study examining acromioclavicular joint congruity after different methods of coracoclavicular loop repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 12(6): 595-598.

- Hessmann M, Gotzen L, Gehling H (1995) Acromioclavicular reconstruction augmented with polydioxanonsulphate bands. Surgical technique and results. Am J Sports Med 23(5): 552-556.

- Gohring U, Matusewicz A, Friedl W, Ruf W (1993) Results of treatment after different surgical procedures for management of acromioclavicular joint dislocation. Chirurg 64(7): 565-571.

- Pfahler M, Krodel A, Refior HJ (1994) Surgical treatment of acromioclavicular dislocation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 113(6): 308311.

- Wellmann M, Zantop T, Petersen W (2007) Minimally invasive coracoclavicular ligament augmentation with a flip button/ polydioxanone repair for treatment of total acromioclavicular joint dislocation. Arthroscopy 23(10): 1132.e1-1132.e5.

- Trainer G, Arciero RA, Mazzocca AD (2008) Practical management of grade III acromioclavicular separations. Clin J Sport Med 18(2): 162166.

- Lee SJ, Nicholas SJ, Akizuki KH, McHugh MP, Kremenic IJ, et al. (2003) Reconstruction of the coracoclavicular ligaments with tendon grafts: a comparative biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med 31(5): 648-655.

- Motamedi AR, Blevins FT, Willis MC, McNally TP, Shahinpoor M (2000) Biomechanics of the coracoclavicular ligament complex and augmentations used in its repair and reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 28(3): 380-384.

- Tienen TG, Oyen JF, Eggen PJ (2003) A modified technique of reconstruction for complete acromioclavicular dislocation: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med 31(5): 655-659.

- Weinstein DM, McCann PD, McIlveen SJ, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU (1995) Surgical treatment of complete acromioclavicular dislocations. Am J Sports Med 23(3): 324-331.

- Collins DN (2009) Disorders of the acromioclavicular joint. In Rockwood CA, et al. (Eds.), The shoulder. (4th edn), Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, USA, pp. 453-526.

- Leidel BA, Braunstein V, Pilotto S, Mutschler W, Kirchhoff C (2009) Mid-term outcome comparing temporary K-wire fixation versus PDS augmentation of Rockwood grade III acromioclavicular joint separations. BMC Res Notes 2: 84.