Knee Surgery: Total Knee Replacement or Partial Knee Replacement

Hedra Samir Hanna Eskander*

Department of Orthopaedic Fellow, St. George private Hospital Kograh, Australia

Submission: November 11, 2016; Published: November 22, 2016

*Corresponding author: Hedra Eskander, Department of Orthopaedic Fellow, St. George private Hospital Kograh, 18/3 West terrace Bankstown, Sydney 2200 NSW, Australia

How to cite this article: Hedra S H E. Knee Surgery: Total Knee Replacement or Partial Knee Replacement. Ortho & Rheum Open Access J. 2016; 3(4): 555619. DOI: 10.19080/OROAJ.2016.03.555619

Abstract

The total knee replacement and the partial knee replacement are both effective at reducing pain in the knee. However, both surgeries are useful for different populations.

Introduction

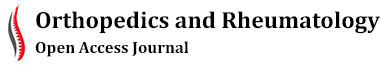

Osteoarthritis commonly affects the knee joint, resulting in joint space narrowing and development of osteophytes and sclerosis of the underlying subchondral bone. Total knee arthroplasty is now considered the surgical treatment of choice for osteoarthritis of the knee. It is indicated in patients over age 65 with degenerative arthritis in two or three compartments of the knee (Figure 1). However, osteoarthritis may involve only one compartment of the knee joint. Unicompartmental osteoarthritis of the knee occurs in the medial compartment in about one-third of patients and in the lateral compartment in about 3% of patients [1]. The optimal treatment for osteoarthritis of the medial compartment or lateral compartment of the knee joint is still controversial. In patients with involvement of the medial or lateral compartment of the knee there are various surgical options, Including arthroscopy and joint debridement, high tibial osteotomy, unicompartmental.

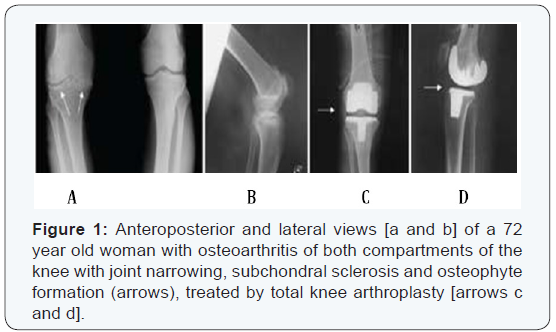

Knee arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty is indicated in patients under age 65 with involvement of either the medial or lateral compartment (Figure2). Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a proven procedure for the treatment of advanced knee arthrosis. However, as much as 20% of these patients have isolated unicompartmental osteoarthritis amenable for a unicompartmental replacement [2]. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) has been performed since the 1970s for these patients with an aim of replacing only the diseased compartment of the knee joint and preserving the bone stock. The initial results of UKA were very encouraging but later proved disappointing and many surgeons abandoned the procedure. The causes of the early failures are multi-factorial and include poor patient selection and surgical technique [3], inadequate implant design [4], polyethylene wear [5], inaccurate instrumentation [6], poor understanding of the knee kinematics

A-Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty (UKA)

Is an established procedure but has been controversial for three decades. Initial results in the early 1970’s were discouraging, however, Introduction of newer techniques of exposure and design Improvements have made this procedure quite popular in recent years. UKA is now being performed with increasing frequency in younger patients [7].

Indications: Original selection criteria was:

- Elderly Patient

- Non-inflammatory osteoarthritis

- Mechanical axis deformity <10 (varus)

- Intact ACL without M-L subluxation

- Flexion contracture <15 degrees

- Body weight < 80-90 kilograms

- P-F joint may have grade II-III changes

Contraindications

- Patients with inflammatory types of arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, are not regarded as good candidates for partial knee replacement. With inflammatory arthritis, more than one compartment is usually involved.

- Previous HTO with overcorrection

- Sepsis

- Cruciate ligament lesion

- Medial or lateral subluxation (usually associated with a torn ACL) 6-Tibial or femoral shaft deformity

- Flexion contracture greater than 15°

- Varus deformity greater than 15° (medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty) 9-Valgus deformity greater than 20° (lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty) 10Flexion less than 110° [8].

- Patellofemoral joint arthritis

Progression of osteoarthritis in the patellofemoral joint after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty is rare, according to some studies. In the Swedish Registry, no unicompartmental knee arthroplasties have required revision for patellofemoral problems [9].

Murray et al. [10-12] reported that residual postoperative pain was independent of the state of the patellofemoral joint, and no knee surgery was revised because of patellofemoral problems. Unicompartmental arthroplasty improves the mechanical axis and patellar tracking and allows more normal kinematics and rapid quadriceps rehabilitation. For these reasons, osteoarthritis of the patellofemoral joint may not be considered an absolute contraindication. However, other investigators and surgeons have reached the opposite conclusion; thus, many consider patellofemoral disease to be an absolute contraindication for unicompartmental knee replacement. For more information.

Benefits and Risks Associated with Partial Knee Replacement

There are benefits to having a partial knee replacement. With this surgical procedure, there is:

- less bone and soft tissue dissection

- less blood loss

- fewer complications

- Faster recovery of range of motion.

- better range of motion overall

There are also risks associated with partial knee replacement. The risks include:

- A higher revision (repeat or re-do) rate for partial knee replacement than total knee replacement 2-potentially worse function after revision of partial knee replacement than total knee replacement 3-revisions can be more complicated than primary surgeries [13].

Complications

The complications after a unicondylar knee replacement are similar to a total knee replacement. These complications include inadequate pain relief, deep venous thrombosis in 1% to 5% of patients, infection in less than 1% of patients, and unexplained pain about the knee. Late complications include loosening of a component, subsidence of the component, degeneration of the other compartment resulting in pain, infection, polyethylene wear, and possible dislocation of the polyethylene component in a mobile-bearing knee replacement. The main concern associated with partial knee replacement is a possible need to have surgery again if another compartment becomes affected. In this case, the patient would have their partial knee prosthesis removed, and it would be replaced with total knee prosthesis [14].

Limitations Preventing the Widespread Adoption of the Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty Procedure in Clinical Practices

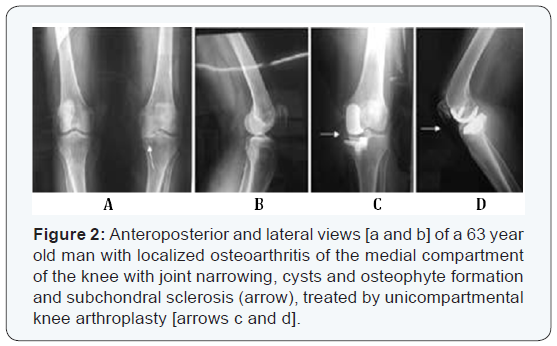

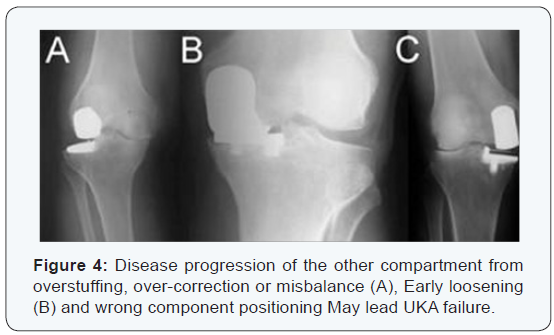

While UKA may have advantages as a surgical option for selected patients who meet the operative criteria detailed previously, TKA remains a popular operation for unicompartmental pathology. The widespread performance of UKA has been limited by the technical difficulty of performing the procedure. In particular, UKA has less tolerance for acceptable component positioning when compared to TKA, as improper component positioning, by as little as 2o, can result in UKA failure (Figure 3) [15-19]. Failures of UKA occur when there is medial-lateral mismatch, inadequate stability of the components, heterogeneous polyethylene wear, improper patient selection (such as performing UKA for bilateral osteoarthritis), aseptic loosening, and tibial Subsidence (Figure 4) [20,21].

Robot-assisted UKA

Although results can be optimized with careful patient selection and use of a sound implant design, the most important determinant of success of UKA is component alignment. Studies have shown that component malalignment by as little as 2° may predispose to implant failure after UKA. Robot-assisted UKA has been projected to address this issue, which combines patient specificity and navigation. Short-term results for robot-assisted UKA are promising, although long-term results are awaited to determine implant survivorship and functional outcome [22].

B-Total knee replacement

Indications:

- Osteoarthritic destruction of the knee is the commonest reason for total knee replacement. This is a disease of synovial joints characterized by degenerative and reparative processes and is seen in 40 percent of 40- yearold’s on radiographic examination. However only 50 percent of these will be symptomatic. Osteoarthritis may be primary or secondary.

- Mechanical derangement such as previous meniscal or cruciate ligament damage, pyogenic infection, ligamentous instability, and fracture into a joint are among the common causes of the secondary type.

- Other causes of cartilage destruction include rheumatoid arthritis, haemophilia, the seronegative arthritis, crystal deposition diseases, pigmented villonodular synovitis, avascular necrosis and the rare bone dysplasia.

Contraindications:Absolute contraindications to total knee replacement include,

- Knee sepsis including previous osteomyelitis, a remote source of ongoing infection

- Extensor mechanism dysfunction,

- Severe vascular disease,

- Recurvatum deformity secondary to muscular weakness, and 5-the presence of a well-functioning knee arthrodesis.

Relative contraindications include

- medical conditions that preclude safe anaesthesia ,the demands of surgery and rehabilitation

- skin conditions within the field of surgery e.g psoriasis, a neuropathic joint and obesity

Complications

- Thromboembolism: This includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT), with subsequent life-threatening pulmonary embolism (PE)

- Infection: Factors relating to a higher rate of infection after TKA include rheumatoid arthritis, skin.

- Patellofemoral complication: Patellofemoral complications include patellofemoral instability, patellar fracture, patellar component failure, patellar clunk syndrome, and extensor mechanism tendon rupture. All have been cited as the common reasons for re-operation. These can be avoided by attention to detail, meticulous technique and the avoidance of component malposition.

- Neurovascular complication: Arterial thrombosis after total knee replacement is a rare (0.03-0.17%) but devastating complication, frequently resulting in amputation. Several authors have recommended performing TKA without the use of a tourniquet in patients with significant vascular disease. Such patients should undergo a vascular surgery consultation prior to their knee replacement.

Peroneal nerve palsy is the commonly reported nerve palsy after total knee replacement. It usually occurs in the correction of combined fixed valgus and flexion deformities, as are often seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. 50% undergo spontaneous recovery and 50% undergo partial recovery with conservative treatment. Some good results have been obtained with surgical decompression.

- Peri prosthetic fractures: Supracondylar fractures of the femur are not common after total knee replacement (0.2% to 1%) They are seen if the anterior femoral cortex is notched and weakened during surgery and in patients with osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, poor flexion, revision arthroplasty, and in neurological disorders. Treatment is with internal fixation or revision total knee arthroplasty. Tibial fractures are uncommon.

Outcome and Prognosis of Total knee replacement

Most patients seem satisfied with their knee replacements and if relief of pain is the main indication for surgery then this should indeed be the case. Satisfactory knee function is usually restored after total knee replacement and the majority is able to return to low impact sporting activity [18]. Long term studies confirm satisfactory functional scores and show 91% to 96% prosthesis survival at 14- to 15-year follow-up. There does not appear to be any difference between PCL-retaining and PCLsubstituting designs. Cement less designs do not have the same length of follow up but studies showing 10-12 years report 95% prosthesis survival [23,24].

Conclusion

The total knee replacement and the partial knee replacement are both surgeries that can change the lifestyle of a person living with osteoarthritis or another knee condition that causes continuous pain. While there are many risks involved with this surgery and a long recovery process, the outcome is worth the work in most cases. The total knee replacement is a more invasive surgery where the bone is cut away and the entire joint is replaced with prosthesis. Recovery is difficult, and usually takes six to eight weeks of intense physical therapy. A partial knee replacement is slightly less invasive, because only one compartment of the knee is cut and replaced, which allows for a quicker recovery and decreased risks. Because only one compartment is replaced, it is less common than a total knee replacement since many patients have injury in more than one compartment and are not eligible for this surgery. The patient still needs physical therapy, but should be able to walk without assistive devices sooner. Both surgeries have their limitations, as full range of motion may never be reached and the patient should refrain from participating in high impact sports such as running. This is because the large amount of force on the knee can degrade the prosthesis more quickly, causing a need to have it replaced sooner [15].

Recommendations

The total knee replacement and the partial knee replacement are both effective at reducing pain in the knee. However, both surgeries are useful for different populations. There is more information about the total knee replacement because it is more common, and generally this would be beneficial to the patient and their wellbeing.

References

- Ledingham J, Regan M, Jones A, Doherty M (1993) Radiographic patterns and associations of osteoarthritis of the knee in patients referred to hospital. Ann Rheum Dis 52(7): 520-526.

- Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, Lidgren L (2001) The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register 1975-1997: An update with special emphasis on 41,223 knees operated on in 1988-1997. Acta Orthop Scand 72(5): 503-513.

- Laskin RS (1978) Unicompartmental tibiofemoral resurfacing arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 60(2): 182-185.

- Bernasek TL, Rand JA, Bryan RS (1988) Unicompartmental porous coated anatomic total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 236: 52-59.

- Lindstrand A, Stenström A (1992) Polyethylene wear of the PCA unicompartmental knee. Acta Orthop Scand 63(3): 260-262..

- Swienckowski J, Page BJ 2nd (1989) Medial unicompartmental arthroplasty of the knee- Use of the L-cut and comparison with the tibial inset method. Clin Orthop 239: 161-167.

- KJoao M. Barretto “Sport activities and unicondylar replacement of the knee”.

- Insall J, Aglietti P (1980) A five to seven-year follow-up of unicondylar arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 62(8): 1329-1337.

- Knutson K, Lewold S, Robertsson O, Lidgren L (1994) The Swedish knee arthroplasty register. A nation-wide study of 30,003 knees 1976- 1992. Acta Orthop Scand 65(4): 375-386.

- Murray DW, Goodfellow JW, O’Connor JJ (1998) The Oxford medial unicompartmental arthroplasty: a ten-year survival study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 80(6):983-989.

- Murray DW (2005) Mobile bearing unicompartmental knee replacement. Orthopedics 28(9): 985-987.

- Weale AE, Murray DW, Crawford R, Psychoyios V, Bonomo A, et al. Does arthritis progress in the retained compartments after ‘Oxford’ medial unicompartmental arthroplasty? A clinical and radiological study with a minimum ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 81(5): 783-789.

- Borus T, Thornhill T (2008) Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 16(1): 9-18.

- Tanavalee A, Choi YJ, Tria AJ Jr (2005) Unicondylar knee arthroplasty: past and present. Orthopedics 28(12): 1423-1433.

- Conditt MA, Roche MW (2009) Minimally invasive robotic-arm-guided unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91(1): 63- 68.

- Pearle AD, Kendoff D, Musahl V (2009) Perspectives on computerassisted orthopaedic surgery: movement toward quantitative orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91(1): 7-12.

- Roche M, O’Loughlin PF, Kendoff D, Musahl V, Pearle AD (2009) Robotic arm-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: preoperative planning and surgical technique. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 38(2): 10-15.

- Banks SA, Harman MK, Hodge WA (2002) Mechanism of anterior impingement damage in total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 84(2): 37-42.

- Whiteside LA (2005) Making your next unicompartmental knee arthroplasty last: three keys to success. J Arthroplasty, 20(4 Suppl 2): 2-3.

- Bert JM (2005) Unicompartmental knee replacement. Orthop Clin North Am 36(4): 513-522.

- Borus T, Thornhill T (2008) Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 16(1): 9-18.

- Pearle AD, O’Loughlin PF, Kendoff DO (2010) Robot-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 25(2): 230-237.

- Bradbury N, Borton D, Spoo G, Cross MJ (1998) Participation in sports after total knee replacement. Am J Sports Med 26(4): 530-535.

- Buechel FF (1994) Long- term outcomes and expectations: cementless meniscal bearing knee arthroplasty: 7 to 12 year outcome analysis. Orthopedics 17: 833.