Toxicity of Cymbopogon proximus (Maharaib) Oil Extract to Newzealand Rabbits

Medani AB1*, Samia MAE2, Ahmed EA2

1Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology, Nile College, Sudan

2Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology, University of Khartoum, Sudan

Submission: March 10, 2016 ; Published: March 29, 2016 ;

*Corresponding author: Medani AB, Assistant Professor of Pharmacology & Toxicology, Nile College, Faculty of Pharmacy, Khartoum, Sudan, Tel: +249912369706; Email: amna_medani@ yahoo.com

How to cite this article: Medani A, Samia M, Ahmed E . Toxicity of Cymbopogon proximus (Maharaib) Oil Extract to Newzealand Rabbits. Open Acc J of Toxicol. 2016;1(2): 555556. DOI: 10.19080/OAJT.2016.01.555556

Abstract

The clinical, pathological, hematological and biological changes in Newzealand rabbits groups given daily oral doses of 0.1, 0.25 and 0. 5 ml/kg body weight/day of Cpmbopogon proximus oil extract were investigated in experiment duration for 21 days. Other than the dose co-related mortality rates, the clinical signs were observed daily after dosing to be low appetite and nervous signs including restlessness and increased consciousness. Pulmonary excretion of the oil extract led to bloody spots on the lungs, lymphocyte infiltration, congestion and edema. Renal glomeruli manifested lymphocyte infiltration in addition to shrinkages and easinophilic material in the medulla, if considered with the corticomedullary generalized necrosis and the significant changes in urea, they may explain the renal dysfunction. Hepatic malfunction was manifested by significant changes in serum alkaline phosphatase and aspartate transferases accompanied by the congested fatty changed livers. The direct physical effect of the extracted oil was detected by the catarrhal inflammation of the intestines. There was no significant hematological change except for the slight changes in RBCs and MCVs in rabbits given the highest dose. Future work for Cymbopogon proximus oil extract was forwarded and practical implications of the result were highlighted.

Keywords: Cymbopogon proximus (Maharaib); Newzealand Rabbits; Oil Extract; Toxicity

Introduction

From the very early history, man is still depending in his struggle against illness on herbal remedies. This suggests the importance of research against poisoning especially in rural areas where the only remedy is traditional health care. Cymbopogon proximus, a member from the lemon-grass genus, also known as gavatichaha in the Marathi language (gavat = grass; chaha = tea) and is used as an addition to tea, and in preparations such as kadha, which is a traditional herbal 'soup' used against coughs and colds [1]. It has medicinal properties and is used extensively in Ayurvedic medicine. It is supposed to help with relieving cough and nasal congestion. AWL [2] was used in folkloric medicine against stomach aches and as an antispasmodic [3]. It is also suitable for use with poultry, fish, beef, and seafood (Figure 1) in Sudan [4-7]. Lemongrass oil is used as a pesticide and a preservative [8,9]. Lemongrass has exhibited analgesic effects in mice and rat studies [10-12]. In a pharmacological study in mice, anti-inflammatory properties of lemongrass oil were examined with 5 |il of lemongrass oil per subject, intra peritoneally [13]. Lemongrass oil has shown antiviral activity against herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) in vitro [14].There were two studies conducted to determine the hypoglycemic properties of lemongrass (Cymbopogon proximus) in alloxan-induced diabetic rats [15,16]. In Costarica, Maharaib was used as an antihypertensive drug [17]. Lemongrass oil also demonstrated vasorelaxation on isolated, perfused, mesenteric artery preparation and appears to be mediated by nitric oxideindependent and non-postanoid mechanisms [18,19]. An oral infusion of up to 208 times the corresponding human dose of lemongrass and oral citral up to 200mg/kg in rats showed no effect on the central nervous system (CNS) as a depressant, hypnotic, neuroleptic, anti-convulsant or anxiolytic [20]. In Egypt it was used for schistosomiasis [21] and as an expectorant.It was proven to have anti hyperglycemic effects on rats if given intragastric in Eygpt [22]. Its antibacterial activity against Pseudomonus aeuriginosa and Staphylococcus aureus in vitro was proven by Farouk [23] who also showed its antibacterial effects on Bacillus subtilis and Eschericia coli. All the above mentioned pharmacological uses of lemon grass were not well supported by toxicological data on the way to avoid adverse, toxic or fatal effects of the traditionally used herb. This study enlightens the dark about one genus of lemongrass that is called in Sudan Maharaib.

Materials and Methods

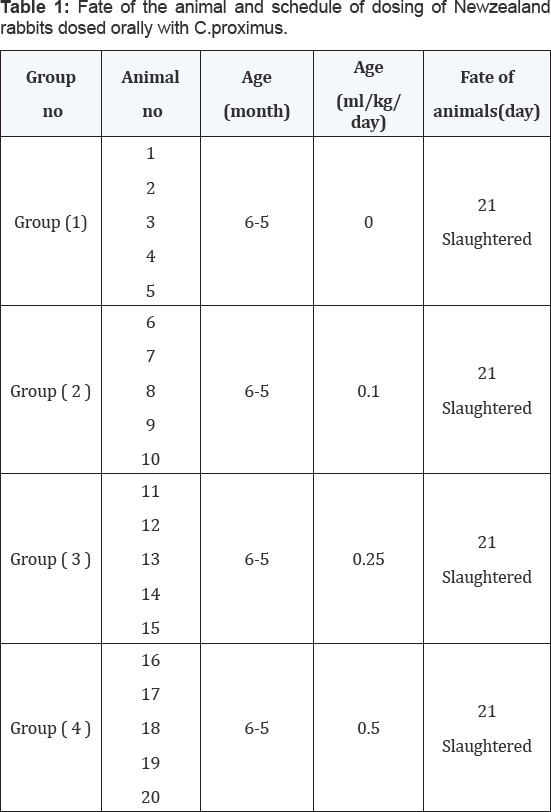

Twenty Sixth month old Newzealand rabbits of both sexes were obtained and health-followed over an adaptation period of 2 weeks. They were then weighed and allotted into four equal groups starting with group (1), the un-dosed control. The herb Cymbopogon proximus was then extracted into an oil and orally given to group (2),(3) and (4) at doses of 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 ml/ kg/day respectively for four weeks. Clinical signs and mortality (Table 1) were recorded .Blood samples prior to experiment and then at a week interval after dosing started for serum constituents (GOT, GGT, ALP, urea, creatinine, total protein, albumin, calcium and phosphorus) and hematological data (Hb, PCV, RBCs, MCV and MCVH).Specimens of tissues from rabbits were taken for histopathological examination.

Extraction method

Wild fruits of the family Poaceae (Gramminae), Cymbopogon proximus (L) Spreng were purchased from the herbalist in Omdurman market (Figure 1) identified and deposited as herbarium specimens at the Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Research Institute, National Centre for Research, Khartoum, Sudan to be dried and crushed coarsely. They were then macerated in a percolator with distilled water for twelve hours. This liquid separated with filtration using cotton to give the appropriate concentrations of the extract. Using Clevenger Apparatus, the oil of the extract was distilled to be passed through anhydrous sodium sulfate.

Statistical methods

The difference between the mean values of data was analyzed by the unpaired student-t-test [24].

Results

Fate of the animal and schedule of dosing of Newzealand rabbits dosed orally with Cymbopogon proximus. The results were shown in Table 1.

Clinical signs

Rabbits in group (2) in-tubated orally with 0.1 ml/Kg/ day of Cymbopogon proximus showed signs of depression and unthriftness. Rabbits in group (3) given oral doses of this herb at the rate of 0.25 ml/Kg/day, had manifested the same signs, but to a larger extend. Rabbits in group (4) receiving 0.5 ml/Kg/day of Maharaib oil extract orally showed a very low appetite and restlessness .The undosed control rabbits in group were normal. All rabbits were slaughtered after 21 days of dosing.

Necropsy findings

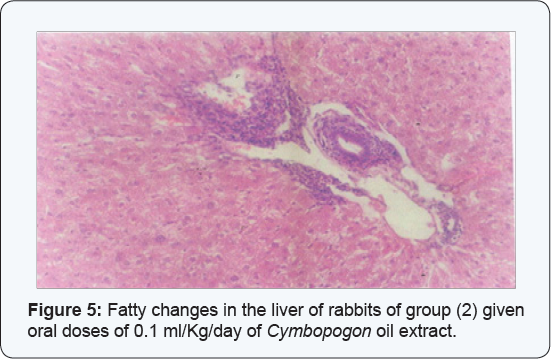

Rabbits of group (2) given oral doses of 0.1ml/Kg/day of Cymbopogon oil extract showed fatty changes in the liver (Figure 2), while those in group (3) dosed with 0.25 ml/Kg/day orally of the extract showed bloody spots on the lungs. Rabbits in group (4) receiving 0.5 ml/Kg/day of Maharaib oil extract orally manifested congested lungs and livers. Rabbits in the undosed control group showed no abnormalities.

Histopathological changes

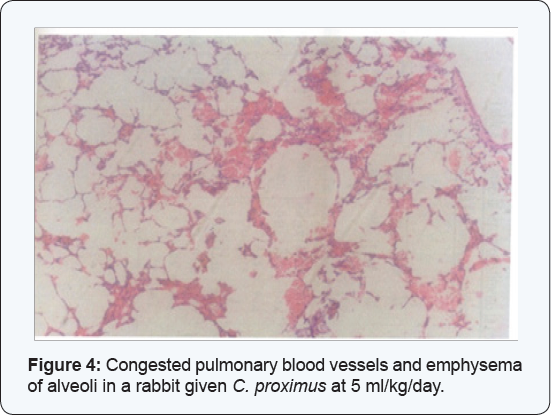

The kidneys of the rabbits of group (2) given oral doses of 0.1 ml/Kg/day of Cymbopogon oil extract showed congestion and easinophilic material in the medulla in addition to lymphocyte infiltration in the medulla (Figure 3).The lungs showed edema, congestion and lymphocyte infiltration (Figure 4). Catarrhal inflammation was observed in the intestines and the livers clarified congestion, fatty changes and slight lymphocyte infiltration (Figure 5).

Serum chemistry

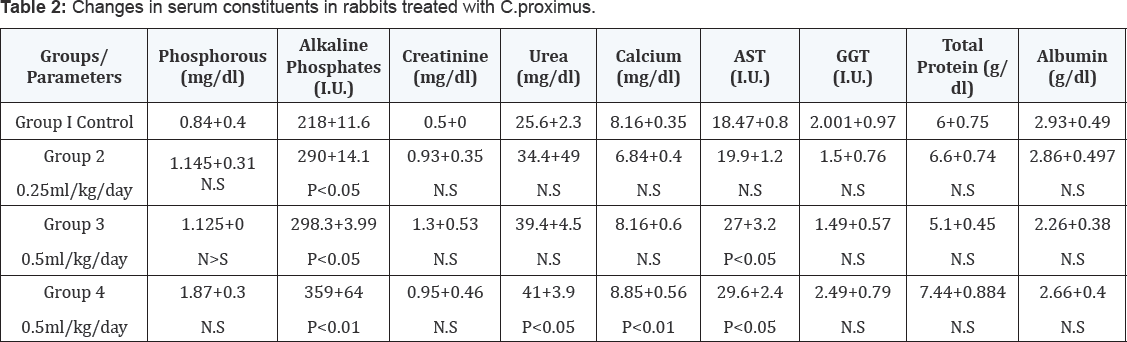

Changes in the activities ofALP,AST,GGT and the concentration of phosphrus, calcium, creatinine, urea, total protien and albumin in the serum of goats dosed with Cymbopogon proximus were entabulated (Table 2). There were no changes in the concentrations of total proteins, albumin, and phosphorus nor in the activity of GGT in rabbits of all groups compared to those in the undosed control group. Urea and calcium concentrations were higher (P<0.5-0.1) in the rabbits of group (4) receiving 0.5 ml/Kg/day of Maharaib oil extract orally ,while GOT activity was higher (P<0.05) in rabbits in group (4) and group (3) dosed with 0.25 ml/Kg/day orally. ALP activity showed higher values (P<0.05-0.01) in all the under-test rabbits compared to the control group of rabbits.

NS= Not Significant, P = Level of significance above or below control value

Hematological changes

There were no changes in the rabbits of all groups in Hb, PCV and MCHC values if compared with the undosed group. Rabbits in group (4)receiving0.5 ml/Kg/day of Maharaib oil extract orally and those in group (3) dosed with 0.25 ml/Kg/day orally showed no differences in the MCH values relative to the control group,, while those in group (2) given oral doses of 0.1 ml/Kg/day of Cymbopogon oil extract showed lower values (P<0.05) .Rabbits in group (4) receiving 0.5 ml/Kg/day of Maharaib oil extract orally showed no significant values in RBCs count , but those of group (2) given oral doses of 0.1 ml/Kg/day of Cymbopogon oil extract and group (3)dosed with 0.25 ml/Kg/day orally showed higher values (PP<0.05) than the rabbits in the control group (1) (Table 3).

NS= Not Significant, P = Level of significance above or below control value

Discussion

On acute exposure of Newzealand rabbits to doses of C. proximus as an oil extract, rabbits showed dose-related signs and were all slaughtered at the end of the experiment. This may indicate the non-fatal property ofthe under-test herb [24-27]. The unthriftness, restlessness, bloody spots on the lung, lymphocyte infiltration, congestion and edema might be probably due to Cymbopogon proximus poisoning as a volatile oil easily excreted via lungs which indicates it as a suggestive inflammatory inducer [28]. The kidneys showed a lymphocyte infiltration in the glomeruli accompanied by shrinkage, hemorrhages and easinophilic material in the medulla and a generalized necrosis in both medulla and cortex which may be the cause of renal dysfunction. The presence of easinophilic material in the lumen of affected tubules and the increased changes in urea and calcium (P< 0.05-0.01) confirm the existence of nephrotoxicity [29]. The necropsy found congestion in the liver of the under-test rabbits, the significantly elevated GOT values (P<0.05) and ALP activity (P<0.05-0.01) are indicative biomarkers of the hepatic insufficiency [30]. The low appetite together with the catarrhal inflammation is pointing out C. proximus as an intestinal irritant [31,32]. Screening of the hematological picture suggested C. proximus as a non endotheliotioxic herb [30]. This toxicological risk assessment of the acute doses of C. proximus clarified this popular herb as a dose dependant, non-fatal, non-endothelio toxic, asthma inducer and hepato-nephrotoxic substance.

Suggestions for future work

As the economic capability of attaining chemical drugs is not always obtained for different uses of the society and as directed by the (WHO) and (UNIDO), people should utilize drugs of local material available at hand which should encourage further investigations to produce proper pharmaceutical preparations to eliminate any possibility of toxicity induced by raw local medicines by conducting experiments using different experimental animals. These trials should be supported by governmental and private bodies to enrich the field of traditional folk medicine with safety data. C. proximus as wild herb that is available for a wide range of believers for medicinal purposes should be investigated for more data and for long term accumulative uses.

References

- Soenarko S (1977) The genus Cymbopogon Sprengel (Gramineae). Reinwardtia 9(3): 225-375.

- Jai Kai (2012) Lemongrass Health Benefits and Healing Properties. Ayurvedic Wellness and Life style. Planetwell.com. 10-17.

- Ross SA, Medgalla SE, Bishay DW, Awad AH (1980) Studies for determining antibiotic substances in some Egyptian plants, part1. Screening for antimicrobial activity. Fitoterapia 5: 303.

- Ali SI, Jafri SMH (1976) Flora of Libya. Tripoli: Al Faateh University, Dept. of Botany.

- Boulos L (1995) Flora of Egypt checklist.

- Hedberg I, Edwards S (1989) Flora of Ethiopia. (and Eritrea. 2000).

- Keay RWJ, Hepper FN (1953-1972) Flora of west tropical Africa. (2nd Edn).

- Shadab Q, Hanif M, Chaudhary FM (1992) Antifungal activity by lemongrass essential oils. Pak J Sci Ind Res 35: 246-249.

- Agron E (2013) Lemon grass as mosquito repellent - WorldNgayon®| WorldNgayon®”. Worldngayon.com. 10-17.

- Lorenzetti BB, Souza GE, Sarti SJ, Santos, Filho D, et al. (1991) Myrcene mimics the Peripheral Analgesic Activity of Lemongrass Tea. J Ethnopharmacol 34(1): 43-48.

- Rao VS, Menezes AM, Viana GS (1990) Effect of Myrcene on Nociception in Mice. J Pharm Pharmacol 42(12): 877-878.

- Viana GS, Vale TG, Pinho RS, Matos FJ (2000) Anti nociceptive Effect of the Essential oil from Cymbopogoncitratus in Mice. J Ethnopharmacol 70(3): 323-327.

- Kokate CK, Rao RE, Varma KC (1971) Pharmacological Investigations of Essential Oil of Cymbopogonnardus (L) Rendle: Studies on Central Nervous System. Indian J Exp Biol 9(4): 515-516.

- Minami M, Kita M, Nakaya T, Yamamoto T, Kuriyama H, et al. (2003) The Inhibitory Effect of Essential Oils on Herpes simplex virus type-1 Replication in vitro. Microbiol Immunol 47(9): 681-684.

- Mansour HA, Newairy AS, Yousef MI, Sheweita SA (2002) Biochemical Study on the Effects of Some Egyptian Herbs in Alloxan-induced Diabetic Rats. Toxicology 170(3): 221-228.

- Sheweita SA, Newairy AA, Mansour HA, Yousef MI (2002) Effect of Some Hypoglycemic Herbs on the Activity of Phase I and II Drug-metabolizing Enzymes in Alloxan-induced Diabetic Rats. Toxicology 174(2): 131-139.

- 17. Gupta MP, Arias TD, Coorea M, Lamba SS (1997) Ethnopharmacognositic Observations on Panamanian medicinal Plants, Part1, Quartarnary Journal of Crude Drug Research 17: 115.

- Abeywardena M, Runnie I, Nizar M, Suhaila M, Head R, et al. (2002) Polyphenol-enriched Extract of Oil Palm Fronds (Elaeisguineensis) Promotes Vascular Relaxation via Endothelium-dependent Mechanisms. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 11(Suppl 7): S467-S472.

- Runnie I, Salleh MN, Mohamed S, Head RJ, Abeywardena MY (2004) Vasorelaxation Induced by Common Edible Tropical Plant Extracts in Isolated Rat Aorta and Mesenteric Vascular Bed. J Ethnopharmacol 92(2-3): 311-316.

- Carlini EA, Contar J de DP, Silva-Filho AR, Silveira-Filho NG, Frochtengarten ML, et al. (1986) Pharmacology of lemongrass (CymbopogoncitratusStapf). I. Effects of teas prepared from the leaves on laboratory animals. J Ethnopharmacol 17(1): 37-64.

- Kloos H, Sidrak W, Michael AAM, Mohrareb EW, Higashi GI (1982) Disease Concepts and Treatment Practices Relating to Schistosomahaematosomain Upper Eygpt. J Trop Med Hyg 85(3): 99- 107.

- Eskandar EF, Jun HW (1995) Hypoglycaemic and Hyperinsulinaemic Effects of Some Egyptian Herbs Used for the Treatment of Diabetes mellitus type (II) in Rats. Eygptian J of Pharmacology and Science 36: 331.

- Farouk A, Bashir AK, Salih AKM (1985) Animicrobial Activity of Certain Sudanese Plants Used in Folkloric Medicine, Screening for Antibacterial Activity (1). Fitoterapia 54: 3.

- PCPC (2005) Pharmacopoeia Committee of the Poeple's of China. Pharmacopoeia of the Poeple's Republic of China. Chemical Industry Publishing House, Beijing, China.

- VPCRC (2005) Veterinary Pharmacopoeia Committee of the Republic of China. Veterinary Pharmacopoeia of the Poeple's Republic of China.

- Xu XW (2006) Toxicity Classification Exploration of Toxic Herbs. Zhejiang J of Trad Chin Med 41(5): 308.

- He XY (2007) Classified Study on the toxicity of 615 Kinds of Common Tradional Chinese Medicines. China Pharmacy 18(30): 2392-2394 .

- Leite JR, Seabra Mde L, Maluf E, Assolant K, Suchecki D, et al. (1986) Pharmacology of Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citrates Stapf). III. Assessment of Eventual Toxic, Hypnotic and Anxiolytic Effects on Humans. J Ethnopharmacol 17(1): 75-83.

- Fujita SI, Fujita Y (1972) Miscellaneous contributions to the essential oils of the plants from various territories. XXX. On the components of the essential oils of Cymbopogon goeringii A. Camus. Yakugaku Zasshi 92(10): 1285-1288.

- Sinha S, Jothiramajayam M, Ghosh M, Mukherjee A (2014) Evaluation of Toxicity of Essential Oils Palmarosa, Citronella, Lemongrass and Vetiver in Human Lymphocytes. Food Chem Toxicol 68: 71-77.

- Lalko J, Api AM (2006) Investigation of the Dermal Sensitization Potential of Various Essential Oils in the Local Lymph node Assay. Food Chem Toxicol 44(5):739-746.

- Wilson ND, Ivanova MS, Watt RA, Moffat AC (2002) The Quantification of Citral in Lemongrass and Lemon Oils by Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. J Pharm Pharmacol 54(9): 1257-1263.