Abstract

This work evaluates the potential for encouraging creativity through visits to museums. An aspect which interests us is the aesthetic of the museum and how promoting visits can become a process of getting to know the creative possibilities concealed by the museum spaces themselves. We studied inclusive creativity in Secondary school, researching the link between educational centers and museums. We considered that the level of creativity of students can be improved by taking advantage of museum visits. We have focused our study on seven museums in the city of Valencia, highlighting elements that we consider important in stimulating creativity.

Keywords:Museum; Creativity; Secondary School; Teacher Training; Heritage Education.

Abbreviations: PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment; IVAM: Valencian Institute of Modern Art; MuVIM: Valencian Museum of Illustration and Modernity.

Introduction

It is necessary and urgent to review what we are doing in order to promote creativity in young people. There is an urgency because the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests will incorporate creativity as a detail to be highlighted in its barometer of quality of the educational applications among developed countries. In the Spanish context, formal education is very dependent on the transfer of information and knowledge, which is usually to the detriment in creative thinking training. Art education at the various educational stages is proof and not too much interest on the part of Spanish curriculum. Art education, one of the pillars of encouraging creativity in the educational sphere is in its worst situation for decades with regard to its presence in the curriculum. Arts education has diminished disproportionately in the last few years, which has more or less led to the disappearance of this subject being developed in the classroom. This should be taken into account in regard to the lack of interest in creativity observed in educational policy. With such an unfavorable situation, our approach is to promote training in creativity in students. In the present study we focused on secondary school pupils and how to encourage their creativity during visits to museums.

Museums represent valuable spaces, whether they are public or private institutions. They are important shop windows for the heritage of which they are the authority. Each museum is conscious of its role as an image of the institution it represents. The images of a museum convey the spirit of the institution itself, the images of each museum help us detect the extent to which the design of the spaces becomes a showcase of the brand to which it pertains (private collection, city hall, council, ministry). With the Proyecto Dechados (Paragons Project) it was our aim to improve creativity in secondary education institutions, with particular emphasis on visits to museums. Accordingly, an important aspect to highlight is the relationship that exists between secondary schools and museums. The objective of the study is established especially in the observation of visits. The Proyecto Dechados is originated from the CREARI Cultural Pedagogy Research Group (GIUV2013-103).

The museum is an educational environment which creates, cares for, builds and facilitates enjoyment. A necessary educational environment for people who have the vision, who bring it to fruition, share it, interpret it and transform it in accordance with the needs which arise. It is an educational environment designed from an artistic and sustainable perspective and it must be a space for collaboration and to take on challenges [1]. It is necessary to be mindful of the new proposals for educational spaces which arise from heritage and the arts, encouraging a very complex process which draws on doubt, but above all hopes and aspirations [2].

Both the permanent collections and temporary exhibitions present great examples for ascertaining the image of the museum from the Visual Culture [3]. We studied these heritage surroundings, getting to know the potential for expression that the different constructive and composition elements comprise. Decoration of the interior zones and design of the spaces is a source of aesthetic knowledge for young adolescent visitors [4]. When people visit museums, there is an educational process going on both in terms of the reason for the visit itself, as well as all the cultural and aesthetic stimuli that every visitor receives while there. Using an Arts-Based Research perspective we looked at aspects such as architecture, spaces, interpretation, signage design, ornamental elements, interior decor and the formal aspect of each institution [5]. Among the research results, what stands out is the impact that the design of these surroundings has on its visitors, as well as the implicit value of the communication policies of each museum.

Energy and aspiration, capacity and good practice, accompanied by an adequate budget and the support of those who manage it, create a space for ideas and laboratories for educational and artistic engagement. In architecture, we understand that all construction must make a compromise with its location and by extension, with the environment, which presents formal and aesthetic aspects. At the Creari Research Group we have many years’ experiences of research and dissemination of our work with studies where we discuss the importance of exhibition space on the museum, the essential role played by museums’ educational representatives, the new sense of heritage, and the new educational settings which are being generated in different formal and informal contexts. Figure 1

The image of the museum begins with the publicity we consume, especially online [6]. And when it comes to tourist towns and cities like Valencia, the information is produced predominantly from institutional campaigns and tour operators. Tourism is making changing considerably the use we make of urban cityscapes, including the lifestyle of the residents, given that there is an ever-widening division between constructed spaces and the people who make use of them, between the built environment and the lives people live [7]. The neo urbanite is a mix of the tourist, the native and the migrant who exchange customs and coexist peacefully. There is a city of restricted access, with exclusion, where the residents have become tourists, foreigners, almost like voyeurs in their own city [8].

Every museum develops its image in accordance with the elements it decides to highlight, normally the building, the architecture. In respect of visits to museums by groups of students, we always recommend a prior visit to the museum space in order that the group leader can get familiar with the place and prepare for the academic activity which will take place [9]. Thus, it is advisable that, from an initial observation of the website, we deal with design issues. The information, structure and relationships which are established by the website’s content must be perceived by the users both at graphic level as well as programmatically [10]. The instructions which are provided to explain the content must not only focus on characteristics such as form, colour, orientation and sound. Any design must present an adequate minimum contrast ratio between text and background and between nontextual elements. In our study we began the analysis of each case with a brief review of the institution’s website [11].

Experiences can be provided which inspire creativity by use of space, design and colour, in particular based on the way in which the elements are provided: texts in vinyls mounted on walls, billboards, signage and objects. It is about offering a pleasant and relaxed environment, building a comfortable space where visitors can feel at ease. In this way we find ourselves in a place where we can learn, not just about art or design, but also via contact with the people with whom we share this interest, generating reflections which enable us to consider aspects such as respect for diversity, sustainability or the appropriate use of resources. This type of reflection makes us more creative [12]. Figure 2

The assembly of the exhibitions must keep in mind people of all ages, including students at all educational stages. Simple processes can enable attractive, participatory and fun graphic formats, enabling educational professionals to convey to students the interesting content offered by the materials exhibited: disposal, design, narrative. The fact that achieving exhibition curations, from the pedagogical perspective involves the department of education itself in this task, constitutes a complete success given that it is not always easy to Programme such educational activities [13]. That the proposals promote the visits as a leisure activity enhances the educational function of the exhibitions. The positive results of this type of experience must be utilized in order to continue encouraging new artistic, education and design aim as well as empowering the pedagogical users of the museum [14].

Public and educational programmes are the basis through which a cultural institution relates to society. They are a substantial part of their corporate identity. The educational departments must be conscious of their institutional potential, acknowledged in terms of management of the budget and human resources as well as the support of the centre administration and management [15]. The great success of initiatives can arise from the lighting, graphic elements, or in the adequate use of colour, which can be attractive for people of any age [16]. Each colour offers us a concept, thus if one of the environments is more considered to decode ideas about the exhibitions, the other prompts us to intervene and in the next we can share creative experiences, using the most diverse techniques [17]. It is appropriate to utilize minor signage, to have adequate accessibility, to devote time to observing, relaxing, reflecting, looking, commenting, thinking, listening, sharing, debating and of course also to generate action [18]. When we visit an exhibition space we can share ideas with other visitors, groups of people who derive from their visits the chance to learn, each one participating based on their own interests and desires. Ultimately, it is also about encouraging creativity [19].

Methodology

The methodology we opted for is a qualitative case studies [20], based on a model of observation [21] which encourages actions that promote creativity in secondary school students in a research process which values what is being done in those centers, especially during visits to museums. We mixed a methodology set, incorporating Arts-Based Research methodology. This second dimension is, above all in the images we provide, which are not photographs to “illustrate” the search, but which are connected with a visual discourse, parallel to the written discourse [22].

From an international perspective, attending to social questions, Eleanor S. Armstrong is in favor of incorporating inclusion to the museum space by means of tours which create an eccentric perspective, implementing research activities which share scientific methods, such as the case with the science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine (STEM) perspective, which can benefit the visitor by developing scientific knowledge (the author being focused on science museums), that is, theorizing at the same time what is used as a method of cocreation, involving the participating public [23]. All that benefits diversity, as an element to be favored as a creative focus [24].

It is essential to consider the graphic images of museums, given the relevance for educational settings in that the latter give cultural coverage to many academic activities [25]. It is in many senses about training citizens, both from the aesthetic perspective as much as in the area of humanities and also from empowerment of the teaching staff and the educational media personnel. It is our desire that the approach towards a courageous and sustainable design continues to exceed the margins of the predictable, in order that these museum spaces continue to have a place both for motivating and stimulating experiences, opening up frontiers to new audiences and that they bring about the desired scenarios of respect and attention to the citizenship that we need [26].

The research objectives are: 1) To analyse design elements in the different museums; 2) To incorporate creativity and design into teaching with a critical education focus. 3) To develop competencies related to education and creativity. 4) To utilize visits to museums to stimulate creativity in secondary school pupils. 5) To implement visits to the website of the museum to prepare for visits. With all that, we aim to create a new perspective on the museum and to develop opportunities to Programme the future, in terms of the creative practices in educational settings, especially in the field of Secondary school [27]. We want to generate a space for reflection without losing sight of the involvement of the pupils and teaching staff from the schools [28].

For John Dewey education is a process of reorganization, reconstruction and continuous transformation, where both the children and the adults are dedicated equally to growth [29]. We cannot forget the lesson of the artist Louise Bourgeois, who inaugurated the Hall of Turbines at Tate Modern in 2000 with her sculpture entitled ‘I Do. I Undo and I Redo’. In this spectacular installation there were life indicators (by then the artist was already eighty years old). Each of the three towers and staircases measures nine meters in height and it was crowned by mirrors which reflected in all directions. When you go up, you can sit on a seat to observe (or to be observed), thus revealing an intimacy which is scary. There were constant allusions to the figures of the mother and the child by means of a series of elements which made reference to that maternal relationship. The mirrors reflected the encounter between those who were participating with the looks and the architecture of the enclosure. In fact, the towers had been constructed with materials recycled from the old turbines from the electricity power station where the Tate Modern stands today. The family space as shelter and courage, the closeness of the home establishes again the intimacy of the museum.

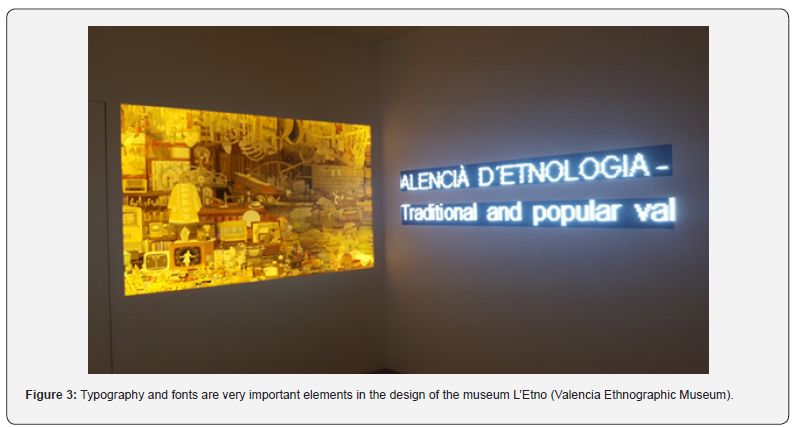

The similarity between “I Do, I Undo and I Redo” of Louise Bourgeois and a good design of the museum environment starts from the similarity of their criteria for concept and development (figure 3). In her work on human relationships, Bourgeois was speaking to us in her work into human relationships, of fathers and children, of doing and not doing, constructing worlds, reconstructing looks, establishing new encounters. A museum also looks at those same places. The paths taken by both have similarities given that they are open to interpretations and sentiments. Participation is constituted from the space itself. They are spaces which permit an aesthetic practice but also a significant learning which flows in all directions [30].

“Intimacy is politics”, was the title of an important exhibition conceived by the curator Rosa Martinez for Met Quito (Metropolitan Cultural Centre, Quito, Ecuador). It is through art and design that we present a panorama of daily actions and of problems from personal to social and that they give the personal nature of an act political dimension. The environment that is achieved by creating well designed spaces is enormously evocative of the setting of the artist’s workshop, that magical place which encapsulates doubts, expression and creativity. In some installations the intimacy of the artist’s studio or workshop is transferred to the museum space. There are cases where staff from a museum’s education department have managed artistic content to discover the possibilities of art as a habitable space [31]. What a good design can achieve is to create a contemporary debate, which looks towards the future, which takes as its basis the practices favored by the “educational journey”, and the summary of all these factors combine to make a place of interaction with the space, colours, objects, ideas and sensations [32]. On the other hand, it depends on an analysis which is more focused on the role being played by the digital universe when it comes to visits to museums.

Reviewing the role of design in a society marked by digital images involves attending to current needs, especially of a younger population. Environments constitute the beginning of a positive approach to carrying out good practice in education [33].

Thus, whoever work son the theme of educational environments defends this both from an artistic educational as well as aesthetic viewpoint. It is the initial environment which grabs our attention, given that it is marked by its dimensions and also by the routes around the museum. The Dutch architect Rem Koolhas said that the routes are rarely simple, thus in their works submits us to circulate, to the necessary apprehension of a significant density of occurrences, transforming our route through into an experience over and above that which is strictly the principal objective of the tour, sometimes separate from the traditional requirements of functionality and economy of trajectory. It is very difficult to find in the world of wide and spacious educational museum spaces. It is necessary to increase the space and the time to learn, and it is an effort that unites the professionals devoted to design and education: to dedicate a time for reflection, taking on the results of a series of initiatives to be undertaken [34]. Figure 4

Our objectives to innovate in the present should provide for changes that can happen in the future, taking account of the digital drift, the problems of eco-diversity and of course educational inclusivity. In order to improve the current landscape, we aim to generate a meeting space for teaching professionals, thus encouraging a collective spirit of integration among Secondary school teachers. We encourage greater closeness between teachers receiving their initial training and continuous professional development of those already working, designing action plans for the different geographical settings and at the educational level, creating a network between the Secondary schools to stimulate new research and prepare teachers for education research. We mark lines of priorities for work in respect of encouraging education in design, taking account of more advanced and innovative curriculum criteria and all that involves ICT in the new concept for generation and dissemination of images [35]. Ultimately, it is about coordinating work between universities and secondary school teachers in order to promote education in design from the everyday, working to achieve wellbeing, doing things well [36].

Experimental framework of the research

The current Proyecto Dechados emerged from experiences linked to a previous innovative educational project entitled “Second

Round: Art and Disputes in Secondary Education”, thanks to which we have developed an important network of contacts among secondary school teachers. From the work carried out in the past seven years, we have a database and previous studies which converge in the current project. Thus, we have prior knowledge of the teaching reality in terms of secondary school education. What we are doing now is developing a comparative study of the design elements that we have observed at 7 museums in Valencia: Museo de Bellas Artes, IVAM (Valencian Institute of Modern Art), Museum of Prehistory, l’Etno Museum of Ethnology, Bombas Gens, MuVIM (Valencian Museum of Illustration and Modernity), Museum of Ceramics. From each museum we took graphic design elements: billboards at the façade and on the exterior of the buildings, graphic elements of routes through the exhibitions, interpretation labels of the works exhibited in the permanent collections, signage within the buildings, publicity in other places within the city. From these elements observed and analyzed we developed a comparative study of the role assigned to each element, taking into account the setting in which they are placed, with the aim of establishing a series of defining categories of the theme being studied.

We went on to analyse the graphic elements in the different museums, these being six public entities and one private. In particular, we looked at the physical aspects of the museums, given that in all cases these institutions occupy their own building. We also evaluated the museums’ websites, although detailed analysis of the digital aspects must be carried out in another piece of research more focused on virtual environments. As we were interested in the physical aspects of the spaces, we observed the placards and signage provided in the different settings of each museum, indicating the adequacy of the graphics, in terms of whether they constituted an efficient dialogue with the visiting public.

Museum of Fine Arts

The website of this important museum has recently been updated. In a background dominated by white, we find seven dropdown sections/menus (Visits, Collection, Exhibitions, Education, Communication, Activities, Sorolla). The catalogue of the collection is organized by traditional techniques: sculpture, painting, drawings, prints, sumptuary arts and archaeology. The billboards at the museum are discrete, always using a subtle combination of the range of colours of each exhibition room with printed texts in vinyls or on posters. They have often opted to incorporate brief explanations about the exhibits. Typography uses predominantly serif-type. The architectural design of this museum is as eclectic as the number of entities which form part of the governing. On one hand, you can find the original renaissance building, accompanied by the neoclassical cupola (reconstructed) which nowadays accommodates the reception, as the zone feeding through to the different entrances to the halls housing the exhibition spaces. Another intermediary zone is the cloister of Ambassador Vich, a reconstruction of which was the patio with pillars from the house of the Ambassador of Pope Borja in Rome. This sumptuous patio takes us to the newest space in the museum which houses the 19th Century painting and sculpture collection, leading to an area dedicated exclusively to the works of Joaquim Sorolla.

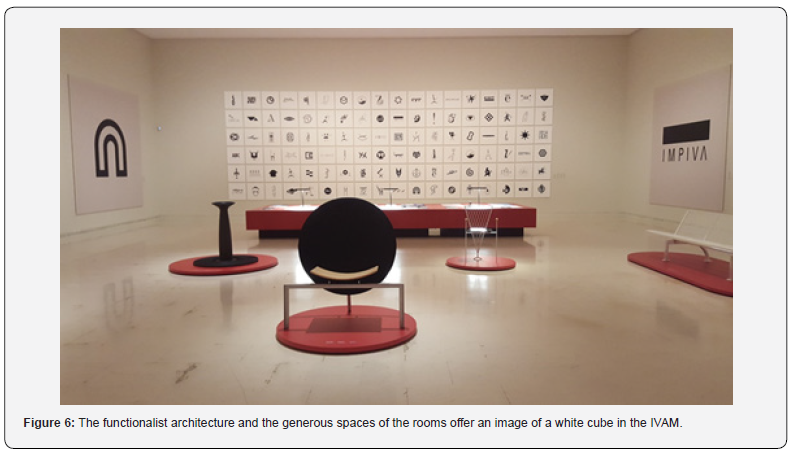

Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM)

The Valencian Institute of Modern Art arrived in the neighborhood of Carmen de Valencia in 1989, during the boom period of spectacular architecture. It had a destructive impact on the area, with expropriated residences, breakdown of the urban fabric and lack of care towards those affected by the disruption. Decades after this, the feeling of disaffection towards the neighborhood still persists, although the museum, thanks to the financial injection from the Generalitat, has been able to achieve a significant place in the international landscape. Access is via a glass vestibule comprising three floors, covered by a slab and a large projection which confers a great monumental nature on it. The building is organized on two axial axes that respond to a sequence between entrance and events hall and transversally the exhibition areas. The great height of the entrance with staircase gathers up the two exhibition floors from the interior walkway which has on the upper floor a succession of exhibition rooms with a continuous skylight. The entrance ticket to the IVAM bears a very visible logo of the museum, originally the work of artist Andreu Alfaro, but which has been converted into four capital letters. The branding is highlighted on the centre’s website, where again we find white as the dominant element. Black typography informs us of the banners in which there are photographs of each exhibition or activity. Figure 6

After the pandemic the museum has eliminated the majority of paper-based information (flyers, posters, etc.), focusing on web-based information. There has also been a revision of the format of the previously very large catalogues, being reduced to far fewer pages, which can also be downloaded free as a pdf. The explanatory vinyl panels on the wall (all in three languages) continue with the original branding of the museum, thus in each room we find a description of what we are seeing. This written interpretation helps to consolidate the spirit of the exhibit, taking into account that contemporary art can be rather labyrinthine (conceptually speaking) for a lot of visitors. There is internal signage in the interior to help visitors find their way around (WC, restaurant-cafeteria, rooms, auditorium, lifts, emergency exits).

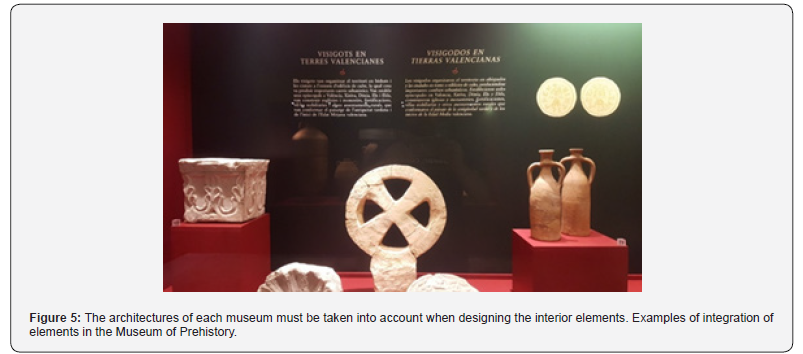

Museum of Prehistory

A visitor to this museum is initially hit by the pedagogical

objectives which dominate the environment, a point we already

detected from the website. Immersed in a cultural container from

the Valencia local council called “La Beneficencia” (The Welfare) at

the main entrance indicates clearly the dependencies of prehistory

on the right, on the floors making up the different spaces of the

museum. Of all the examples analyzed, this would be the museum

where most importance is devoted to printed material given that

at the entrance, we are offered illustrated leaflets explaining in

three languages the different dependencies that make up the

collection. The presentation of the dropdowns is very instructive,

for example giving information about each species:

1st Floor. History of money (coins, notes, medals and other

associated materials)

2nd Floor. Iberian culture (funeral ceramics and sculpture) of

Iberian populations.

2nd Floor. Roman world (a route through the 9 centuries from

the arrival of the Romans until the Visigoths).

We proceed through the different dimly lit, warmly colored rooms (ochers, greens, browns), discovering the different stratigraphic layers of the deposits where the exposed pieces are found. One of the most outstanding parts of the museum is dedicated to the route of the Iberians, where there is interesting information on display. But again, the graphic design aspect has made significant concessions to a supposed “pedagogical design”, which mixes excessive typography with a conventional ordering format, like blog content, so that at times it feels like leafing through a text book.

L’Etno Museum of Ethnology (L’Etno Museo de Etnología)

This is the most typographical-oriented museum in the city. Recently awarded the European prize for Best Museum, its overcrowded concept serves to convert the space into a true artistic installation, at the same time as allowing a great quantity of objects to be shown. The texts inundate the rooms, both for purposes of explanation as well as being included in the exhibits themselves. The lighting and spaces make the visit rather labyrinthine, evoking a thousand and one insinuations to each visitor. By being displayed so profusely, the power which the objects emanate amounts to an intense visual experience, replete with cultural suggestions. By its effectiveness from a recreational viewpoint, it is a museum which positively stimulates creativity in its visitors, whatever their age, including secondary school students. In addition, it gives the effect of light, composition and distribution of objects, the graphic resources appear continually, these appear as a character indicating to the visitor what can be found around each corner. There is no doubt that this museum has drunk in the tradition initiated at the beginning of the Twentieth Century by the Henry Chapman Mercer Museum in Doylestown (Pennsylvania). This museum creates in its moment the relationship between immersive experience and technical/technological progress, by means of an aesthetic-cultural analysis of the ideals of modernity and the pre-industrial past, something which is already habitual in the context of the ethnographic archives and folklore museums, the object ology and the traditional ornaments and artisan crafts, whose forms of enunciation and exhibition on a sui generis basis deriving from immersive and exuberant strategies.

Bombas-Gens Art Centre

In the past few years this museum has become a reference centre for artistic activity within the city. Sponsored by a family of business people, who support the Foundation for Love of Art, it has centred its strategy on photographic collections, transferring a major interest by the art works who from a conceptual perspective incorporate bioethical reflections to its artistic discourse. The restoration of an old modernist water pump factory, incorporating elements such as a unique species garden, focusing on the gastronomy and recovering the bomb shelters of the civil war. Such themes are milestones valued by the public and specialists. The graphics are stylistic, combining perfectly with the meticulous restoration of the different buildings which make up the complex. It seems that the future of the centre will involve its incorporation into public management, given the news about the supposed lack of economic solvency of the founders.

Valencian Museum of Illustration and Modernity (MuVIM)

The imposing architecture of this museum was conceived by Guillermo Vazquez Consuegra from Seville. He highlights the extreme use of concrete and playing with levels and using curious angles. Glass and metal surround this showpiece of industrial aspect, converting the building into a true heritage emblem of the museum. In fact, MuVIM does not have a collection, it is a museum without objects, given that its function is based on defending illustration as a documentary of philosophical thought, defending intangible heritage, thoughts and ideas. The exhibitions are based on very diverse themes, without a clear argumentative guide. Clearly graphics are an important element in this museum, which since its inception has freely offered visitors posters and prints of different samples of is graphics in order to disseminate the work of the graphic design professionals.

Museum of Ceramics

This is the only national museum in the city, being a subsidiary of the Ministry. The others we have analyzed are associated with the Generalitat, Diputació and to a private company. At graphic level it is the least polished of all. There are no defined aesthetic criteria, either in terms of information posters and signage or in the billboards and vinyl. However, it is an attractive museum, benefiting from the wonderful architecture of the baroque palace and is one of the most visited by tourists. It also has a lot of success with school and university visits. It is like a box of chocolates, with a busy decoration. There is nothing which stands out in the graphics of the museum itself, but in the building to the side there is a hotel named “Marqués House”, with a very interesting graphic. Figure 7

Observing students during museum visits

One of the contributions of the Dechados project is observing

students during museum visits, taking note of their comments,

gestures, and behavior throughout the activity. This information,

along with pre- and post-visit surveys, provides us with a valuable

source of data that we subsequently apply to the analysis of each

visit. We present as an example a visit observation that captures

the interaction between participants during the activity.

• Between museum staff and teacher: The teacher

demonstrated an active attitude. He participated throughout the

activity and helped out. The group had quite a few students.

• Between museum staff and students: Museum staff

constantly tried to keep the students engaged by using motivation,

asking questions, helping them complete their practice correctly,

and regaining their attention.

• Between museum staff and museum: Because they had a

good understanding of the space, they guided the visit according to

the points where they should be positioned and did not interfere

with other groups and staff interacting in the museum.

• Between students and the museum: The students

participated in the workshop, as well as in all the panels and

spaces where they could interact.

• Between students and teacher: The teacher was attentive

to the students and interacted with them at all times.

How does the museum experience lead to the production of diverse discourses and images, the generation of alternatives, and the imagining of possibilities? The visit begins with an analysis of the changes that have occurred in the city in recent years, and the discourse is made engaging through specific references. The museum experience enables associations of ideas, concepts, and images, connecting distant ideas in a productive way. The museum experience emerges possible or alternative explanations for what surrounds us, helping participants harness their ability to imagine that things could be different, through comparisons between the past and the present, and posing hypotheses for the future. By projecting this discourse into the future, greater attention is gained.

Among the students’ comments regarding the preparation of the visit, we highlight the following, which show the adolescent students’ initial disaffection: -”I don’t like museums, they’re boring”; -”I found the science museum interesting; I’m not interested in the art museums”; -”I like museums where you can play with technology.” After the visit, we observed that the comments were more positive, even emotional in some cases: -”I’m attracted to activities that take place outside the classroom, and if it’s a museum, I prefer it to be about science or technology”; -”I’ve always liked history museums because I read a lot about history, and in the museum you can see original pieces from every historical moment”; -”I used to think art museums were boring, but on the last few visits I’ve really enjoyed them, and I think my creativity has been activated.”

Having carried out observations in museums of very different types (art, archaeology, history, computer science, science), the results of the observations in each case are particular, although in all cases the researchers’ conclusions agree that the activity always resulted in an increase in the students’ creative capacity.

Conclusion

The objective of this research comprised initially in disseminating the Proyecto Dechados (Paragons Project), which encourages the development of creativity in museum visits, focusing on the elements of design of seven museums in Valencia, for the purposes of evaluating the potential impact of the architecture and design of these institutions on the visiting public, especially secondary school students. We discovered that some of the museums analyzed have prioritized design, while others have not devoted so much attention. The differences are significant, but they demonstrate that a museum’s good design concept can permit a greater encouragement of creativity in visitors, given that it activates elements of aesthetic and cultural learning. By observing the visits of secondary school students, we detected that both the architecture as well as the elements within the space itself activate creative thinking. We therefore appeal to a greater interest on the part of institutions to improve everything linked to architectural or interior space design environments, given that they will redound positively in an increase in creative ability among the visiting public. Another aspect to improve is the way in which Secondary school teachers plan and handle their visits where they accompany pupils. We cannot leave these individuals in the background, thus we should implement essential aspects, such as permanent training, research and innovation, and an approach towards art and design education.

Funding

R&D project “DECHADOS. Inclusive creativity in secondary school through the relationship between schools and museums”, ref. PID2021-123007OB-I00, funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain MCIN/ AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the European Union’s ERDF funds.

References

- Huerta R (2021b) Silk Road Museums: Design of Inclusive Heritage and Cross-Cultural Education. Sustainability 13(11): 1-17.

- Morrisey K, Fraser J Ball T (2022) Museums and social issues: Heuristic for creating change. Museum & Society 20(2): 190-204.

- Mirzoeff N (2006) On Visuality. Journal of Visual Culture 5(1): 53-79.

- Davis A, Tuckey M, Gwilt I, Wallace N (2023) Understanding Co-Design Practice as a Process of “Welldoing”. International Journal of Art & Design Education 42(2): 278-293.

- Kuhnke JL, Jack-Malik S (2022) How the Reflexive Process Was Supported by Arts-Based Activities: A Doctoral Student’s Research Journey. Learning Landscapes 15(1): 201-214.

- Han B C (2022) No-Things: Upheaval in the Lifeworld. Polity Press.

- Han B C (2023) Vita contemplativa: In Praise of Inactivity. Polity Press.

- Calvino I (2013) Six Memos for the Next Millennium. Penguin.

- Duncum P (2015) Transforming Art Education into Visual Culture Education through Rhizomatic Structures. Anadolu Journal of Educational Sciences International 5(3): 47-64.

- Wang B, Dai L, Liao B (2023) System Architecture Design of a Multimedia Platform to Increase Awareness of Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Sustainable Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 15: 1-15.

- Rodríguez Ortega N (2018) Five Central Concepts to Think of Digital Humanities as a New Digital Humanism Project, Artnodes: revista de arte, ciencia y tecnología 22: 1-6.

- Whitelaw J (2021) What’s Among and Between Us: Mining the Arts for Pedagogies of Deep Relation. Learning Landscapes 14(1): 421-436.

- Rogoff I (2008) Turning. Journal e-flux, 0.

- Rolling JH (2017) Art + Design Practice as Global Positioning System. Art Education 70(6): 4-6.

- Giroux H (2018) Pedagogy and the politics of hope: Theory, culture, and schooling: Acritical reader. Routledge

- Peterken C, Potts M (2021) Pedagogical Experiences: Emergent Conversations In/With Place/s. Learning Landscapes 14(1): 289-304.

- Munari B (2008) Design as art. Penguin.

- Maia M (2023) A perspective about design cognition to research through making validation in graphic design, grafica 11(21): 91-97.

- Hamlin J, Fusaro J (2018) Contemporary Strategies for Creative and Critical Teaching in the 21st Century, Art Education 71(2): 8-15.

- Stake RE (2005) Qualitative Case Studies. In Denzin NK and YS Lincoln, The SAGE Handbook of qualitative research. Sage.

- Yin, Robert K (2009) Case Study Research. Sage.

- Huerta R (2016) The Cemetery as a Site for Aesthetic Enquiry in Art Education. International Journal of Education through Art 12(1): 7-20.

- Armstrong ES (2022) Towards queer tours in science and technology museums. Museum & Society 20(2): 205-220.

- Lavoie M (2022) Trans Young Adults’ Building Communities: Narratives and Counternarratives of Identity and World Making. Learning Landscapes 15(1): 215-232.

- Lobovikov-Katz A (2019) Methodology for Spatial-Visual Literacy (MSVL) in Heritage Education: Application to Teacher Training and Interdisciplinary Perspectives. REIFOP 22(1).

- Huerta R (2021a) Museari: Art in a Virtual LGBT Museum Promoting Respect and Inclusion. Interalia A Journal of Queer Studies 16: 177-194.

- Giroux H (1990) Teachers as Intellectuals: Toward a Critical Pedagogy of Learning. Bergin & Garvey.

- Smith K, Flores MA (2019) Teacher educators as teachers and as researchers. European Journal of Teacher Education 42(4): 429-432.

- Dewey J (2005) Art as Experience. Penguin.

- Clarà M, Mauri T, Colomina R, Onrubia J (2019) Supporting collaborative reflection in teacher education: a case study. European Journal of Teacher Education 42(2): 175-191.

- Benjamin W (2003) The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility, and Others Writings on Media. Harvard University Press.

- Bourriaud N (2009) The Radicant. Lukas & Sternberg.

- Soto-González MD, Huerta R, Rodríguez-López R (2025) Educational Connections: Museums, Universities, and Schools as Places of Supplementary Learning. Education Sciences 15(5): 543.

- Huerta R, Alfonso-Benlliure V (2025) Museums as Catalysts for Creativity in Adolescence: A Review. Heritage 8: 1-18.

- Huerta R, Monleón Oliva V (2020) Design of Letters in Posters and Main Titles of Disney Imaginary. Icono 14 18(2): 406-434.

- Sennett R (2008) The Craftsman. Yale University Press.