Serving Students with Disabilities in Schools: Medical versus Educational Diagnoses

Ann H Lê*

Sam Houston State University, 1905 University Ave, Huntsville, TX 77340 USA.

Submission: May 03, 2024;Published: May 15, 2024

*Corresponding author: Ann H Lê, Sam Houston State University, 1905 University Ave, Huntsville, TX 77340 USA. Email: Dr.AnnH.Le@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Ann H Lê. Serving Students with Disabilities in Schools: Medical versus Educational Diagnoses. Open Access J Educ & Lang Stud. 2024; 1(5): 555574. DOI:10.19080/OAJELS.2024.01.555574.

Abstract

The role and responsibility of an educational diagnostician, along with the multidisciplinary team, is to identify the educational needs of our unique students. Often, a student may obtain a medical diagnosis from a licensed physician outside of the school; however, this clinical diagnosis may not guarantee qualification for the student to receive special education services and support through an individualized education program. Therefore, the multidisciplinary assessment professionals must possess a solid knowledge-base and comprehension of the assessment interpretations and the effects of the student’s area of weakness to the academic and functional performance to determine eligibility to specially designed instruction under special education services and support.

Keywords: Assessment; Clinical diagnosis; Medical diagnosis; Educational need; Special education; Specially designed instruction; Clinical diagnosis

Abbreviations: IDEA: Individuals with Disabilities Education Act; AI: Auditory Impairment; AU: Autism; DB: Deaf-Blindness; ED: Emotional Disturbance; ID: Intellectual Disability; MD: Multiple Disabilities; OI: Orthopedic Impairment; OHI: Other Health Impairment; SLD: Specific Learning Disability; SI: Speech Impairment; TBI: Traumatic Brain Injury; VI: Visual Impairment; NCEC: Non-Categorical Early Childhood; FAPE: Free and Appropriate Public Education; IEP: Individualized Education Program; LSSP: Licensed Specialist in School Psychology; ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; ADD: Attention Deficit Disorder; ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual; PDD-NOS: Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified; APA: American Psychiatric Association; DSM: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

Medical Diagnoses and Special Education Services

The charge of an educational diagnostician regarding evaluating and assessing students for a suspected disability is vastly imperative. These professionals examine and make recommendations in order to assist in addressing a student’s area of cognitive and academic weakness related to their identified disability. However, in many cases, a student may have been diagnosed outside of the school by a licensed physician and/or in a clinical facility. Does this medical diagnosis guarantee eligibility for the student to receive specially designed instruction through special education services? This brief article strives to bring awareness to educators and parents with regards to the differences in medical diagnosis and the identification of disability in the school setting.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act

Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 2004 and the Code of Federal Regulations 34 CFR 300.8 (a) [1], children with a disability are eligible for special education and related services when the disability has an adverse effect on the educational performances of the student. In the law, Congress states:

Disability is a natural part of the human experience and in no way diminishes the right of individuals to participate in or contribute to society. Improving educational results for children with disabilities is an essential element of our national policy of ensuring equality of opportunity, full participation, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency for individuals with disabilities [1].

Under IDEA, Texas has determined that eligibility for students aged 3-21 to receive special education services and support fall under one or more of the 13 disability categories [2]:

i. Auditory Impairment (AI)

ii. Autism (AU)

iii. Deaf-Blindness (DB)

iv. Emotional Disturbance (ED)

v. Intellectual Disability (ID)

vi. Multiple Disabilities (MD)

vii. Orthopedic Impairment (OI)

viii. Other Health Impairment (OHI)

ix. Specific Learning Disability (SLD)

x. Speech Impairment (SI)

xi. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

xii. Visual Impairment (VI)

xiii. Non-Categorical Early Childhood (NCEC)

Medical Diagnosis

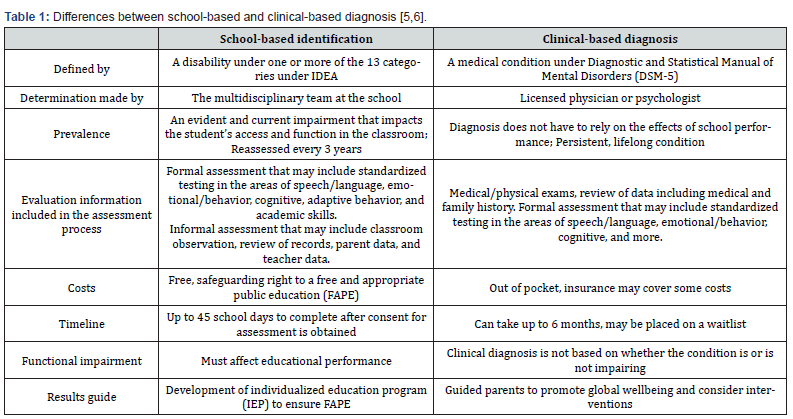

Medical diagnoses have been sought out by many guardians and families at various stages in a child’s life due to concerns with observed delays in mastering developmental milestones and frustrations from longstanding poor performances in school [3,4]. Medical diagnosis and educational identification have varying conditions and outcomes. Understanding the distinction between a diagnosis and a disability will assist parents, families, and school personnel in determining how to address the student’s needs. Table 1 [5,6] provides a brief synopsis of the differences between educational identification and clinical diagnosis.

Diagnoses are performed by medical and clinical professionals. Educational entities (i.e., schools) do not diagnose a child but rather they identify issues as they relate to a student’s education [6]. The multidisciplinary team considers both formal and informal data to assess whether the child’s diagnosis affect his or her ability to access and benefit from general education, or if he or she needs specially designed instruction through special education services. Ultimately, the Individual Education Program (IEP) committee considers the results and recommendations from the evaluation to establish eligibility for special education services.

Outside of an educational setting, parents and guardians have had a difficult time understanding why their child’s medical diagnosis does not afford them special education services. Simply put, a disability must impact the child’s capacity to learn or take part in a public education system. There must be an educational need for services, and these include areas of language and communication, social skills, pre-academic or academic, motor skills, and behavior [6]. In certain instances, a child may qualify for special education services that may be different than their medical diagnosis. The medical diagnosis itself is not what hinders the child from learning; rather the characteristics or factors related to the diagnosis is what affects the student.

All learners have unique strengths and weaknesses. For students with Down syndrome, their educational needs may be supported in an array of settings (e.g., general education with in-class support, or through a modified curriculum in a special education setting). Students with a medical diagnosis of Down syndrome may exhibit varying levels of deficits in language, motor abilities, memory skills, and processing abilities that may meet eligibility under Other Health Impairment, Intellectual Disability, and/or Speech Impairment. Similarly, a child with cerebral palsy (with or without epilepsy) may be eligible for special education services and support under Other Health Impairment, Orthopedic Impairment, Intellectual Disability, or Speech Impairment should the impairment adversely affect their education.

In the state of Texas, the eligibility of Other Health Impairment is determined through a multidisciplinary team that gathers and reviews assessment data and must include but is not limited to an appropriately certified or licensed practitioner with experience and training in the disability (e.g., licensed specialist in school psychology (LSSP) or an educational diagnostician) and a licensed physician [1]. The health problem is chronic or acute, and may include asthma, attention deficit disorder (ADD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), diabetes, epilepsy, a heart condition, hemophilia, lead poisoning, leukemia, nephritis, rheumatic fever, sickle cell anemia, and Tourette's Disorder [1]. The health problem must adversely impact the child’s educational performance, and manifest themselves as having limited strength, vitality, or alertness, including a heightened alertness to environmental stimuli, that results in limited alertness with respect to the educational environment [1]. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is an example of a medical diagnosis, while Other Health Impairment is the disability category that includes ADHD.

The important distinction of medical diagnosis and educational eligibility for special services can also help guardians to be more effective advocates for their child. A doctor can provide a medical diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) by using symptom criteria set in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5). An update from the DSM-IV, the fifth edition of the DSM eliminated the three subcategories [i.e., Autistic disorder, Asperger's disorder, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS)] and grouped all three conditions under the name of autism spectrum disorder [7]. Even with an outside diagnosis, the multidisciplinary team must conclude that the Autism diagnosis interferes with learning and that the student requires specially designed instruction to make academic progress. Guardians and school staff members should view the medical and educational services as systems that work to address the student’s needs. The educational system focuses on the abilities and skills of the student in the academic and functional areas. The medical system, although addresses these areas, do so in a more global standpoint. Medical treatment is developed through a Plan of Care (POC) and may include therapeutic interventions in speech therapy, individual counseling, behavior therapy, occupational therapy, and medication intervention that treat symptoms associated with ASD [7]. While the educational system may be able to provide comparable interventions, the educational need must first be determined and the impact on the student’s access to education must be documented in the educational plan developed through an IEP committee meeting.

Medical disabilities do not always equate to having an educational disability under IDEA. The diagnosis is not the determining factor for a child’s education programming, but rather the impact of his or her disability has on their capability to learn. Should the individual with a medical diagnosis (e.g., cerebral palsy) be capable of full participation in the general education curriculum given only accommodations, without specially designed instruction or related services, this child would not meet eligibility under IDEA. A student who does not meet eligibility for special education services may still qualify for accommodations through Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act.

Educational Need

The determination of eligibility for special education services is made through a multidisciplinary team utilizing an accumulation of both formal and informal sources. Formal assessments can include results from standardized assessments, while informal assessments can be direct observations, parent data, teacher recommendations, and/or surveys regarding the student’s home environment, language skills, adaptive behavior skills, and more [5,6]. The identified disability must adversely impact the student’s educational performance academically and/or functionally. If the student’s disability does not affect his or her educational performance, then the student does not qualify for an IEP through special education services. However, parents and educators must make the determination not only through the review of a student’s academic performance (e.g., grades, state testing scores, and academic progress), but also the student’s functional performance (e.g., skills in the areas of social, emotional, adaptive, and executive functioning) in the classroom setting [8].

Parent and School Collaboration

Parents and school personnel should work towards a team approach to ensure educational success for the student. Any outside medical diagnosis should be shared with the school. Such information will assist the child’s teacher and other staff members to determine how to best meet the student’s educational needs [9]. A disability label should provide more access to educational opportunities to a child, not limit them. When a child is identified as having a disability under IDEA, the schools do so to safeguard that a student is eligible to receive special education or related services, not to take away from their individual strengths or lowering the expectation of their access to the general curriculum.

Conclusion

Educational diagnosticians employ special education assessment procedures and deliver analytic data for students with suspected disabilities. These assessment professionals must have a strong foundation and understanding of the elements and methods involved in the identification of disabilities as defined by IDEA to determine eligibility validly and reliably. This short article served to provide a quick glimpse of the differences between a clinical-based diagnosis and a school-based educational identification of a disability to assist both school personnel and families in determining best practices to address a student’s educational or global needs.

References

- (2004) Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. 1400.

- US Department of Education (2024) Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

- Fuschlberger T, Leitz E, Voigt F, Esser G, Schmid RG, et al. (2024) Stability of developmental milestones: Insights from a 44-year analysis. Infant Behav Dev 74: 101898.

- Lake JF, Billingsley BS (2000) An analysis of factors that contribute to parent-school conflict in special education. Remedial and Special Education 21(4): 240-251.

- LeBlond M (2018) Web Psychology.

- Rosen P (2018) Understood.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub.

- Cantu D (2015) Role of general educators in a multidisciplinary team for learners with special needs. Advances in Special Education 35-57.

- Petley K (1994) An investigation into the experiences of parents and head teachers involved in the integration of primary aged children with Down syndrome into mainstream school. Down Syndrome Research and Practice 2(3): 91-96.