Effects of Stationary Stability Balls on Attention for Students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Carla Miller J1 and William Sweeney J2

1South Dakota Parent Connection, Sioux Falls Schools, Sioux, USA

2Special Education Program, Division of Educational Leadership, School of Education, University of South Dakota, Vermillion, USA

Submission: January 31, 2024;Published: February 16, 2024

*Corresponding author: William Sweeney J, Special Education Program, Division of Educational Leadership, School of Education, University of South Dakota, Vermillion, USA

How to cite this article: Carla Miller J and William Sweeney J. Effects of Stationary Stability Balls on Attention for Students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Open Access J Educ & Lang Stud. 2024; 1(3): 555564. DOI:10.19080/OAJELS.2024.01.555564.

Abstract

This single subject research study examined the effects of stationary stability balls on attention in the regular education setting. This single subject is for students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Students with ADHD participated in the study by first using a traditional classroom chair during instructional activities followed by using a stability ball as a chair during instructional activities. An ABAB design was used to evaluate the student’s level of attention while seated on a regular classroom chair and when seated on a therapy ball during structured learning activities in a whole group setting within the regular classroom. The effectiveness of using stability balls to improve attention of students with ADHD on on-task behavior was inconclusive. A discussion of the importance of empirically validated intervention to improve student’s behavior in the classroom was discussed.

Keywords: Stability Balls; ADHD; Behavioral Interventions; Electroencephalograms; Empirical research

Introduction

Across the country in numerous classrooms, inattention affects student engagement and learning. The number of children and adults receiving a diagnosis for chronic attention problems continues to increase [1,2]. Five to ten percent of students worldwide received a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [2]. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was defined as a neurological disorder that affects a student’s ability to attend in structured academic settings well enough to benefit from instruction. The condition appears as one of the most frequently diagnosed disorders in childhood, second only to autism spectrum disorder [1,3]. The American Psychiatric Association [1] considers ADHD as a lifelong disability, meaning that, although symptoms may lessen or change through treatment, the condition persists throughout the student’s lifetime [4]. Therefore, professionals need to utilize best practices when choosing strategies to lessen the impact of ADHD on learning.

Portilla et al. [5] identified the importance of finding affective strategies to lessen the deficits of ADHD. They examined teacher-child relationships and child behavior from kindergarten through first grade as a predictor of future school engagement and success. They concluded that issues with inattention and impulsive behaviors in the fall of the kindergarten year resulted in greater conflict between teachers and children throughout first grade and beyond [5]. Children’s deficits in self-regulation (e.g., sustained attention to task and impulsivity) affected the quality of their relationship with their teachers, school engagement, and future academic competence. Likewise, the children were determined to frequently achieve lower grades in academic areas than their peers [5]. Students found to struggle with both inattention and hyperactivity performed significantly lower on academic tasks [6]. However, in a study regarding the effect of ADHD behaviors on academic achievement, Merrell and Tymms identified inattention as the behavior most associated with under achievement in math and reading. This research indicates that inattention, rather than hyperactivity, is the most important indicator of school graduation [6].

Data was collected from parents and teachers that included over 2,000 children across a twenty- year period [7]. Teachers were asked to observe and record episodes of lack of focus, absentmindedness, distractibility, restlessness, fidgeting, and out of seat behavior. The research concluded that only 29% of students with attention problems graduated from high school, whereas 89% of students who did not present with inattention problems graduated [7]. ADHD requires long-term, ongoing monitoring and treatment. Most treatment involves some form of strategy and structure in the home and classroom, cognitive and/ or behavioral therapy and coaching, and medication management [8]. Research indicates that a combination of structure and supports, behavior modification, and medication management yield the best treatment outcomes [9-11].

Over the years, many theories about effective strategies used in the treatment of ADHD emerged, including the use of sensory integration strategies [11]. While many strategies developed through sound research methodologies and empirical studies, controversial or fad therapies also emerged [12]. Jacobson and his colleagues compiled an anthology of articles addressing the concern for fad therapies. A fad therapy was defined as a “procedure, method, or therapy that is adopted rapidly in the presence of little validating research, gains wide use or recognition, and then typically, fades from use – usually in the face of disconfirming research, but often to the adoption of a new fad” [12]. Unfortunately, limited studies support strategies based on sensory integration therapy as valid treatments [13]. Many studies about sensory integration contained flawed methodology. Sensory integration therapy, therefore, was identified by them as a fad therapy [12]. However, despite questionable evidence, teachers with well-meaning intent appear to adopt the use of sensory techniques to meet the needs of students with ADHD in their classrooms [12].

Debate concerning whether sensory integration deficits present as a co-exiting feature of ADHD persist [14]. Much of what is known about sensory processing and theories about the effect on individuals with developmental disabilities, come from the field of occupational therapy [15]. In fact, the Occupational Therapy Association, OTA, helped develop standards and practices for therapists to follow with students based on this previous hypothesis and potentially flawed research [15]. Miller et al. [16] conducted a pilot study on the effectiveness of occupational therapy for children with sensory disorders. They concluded that previous studies were not rigorous enough to make valid conclusions and that there was a lack of consensus within the professional community regarding the value of occupational therapy using a sensory integration approach [16]. These authors stated that, “the only conclusion that can be drawn after 35 years of single, non-programmatic research projects is that the evidence neither disproves nor confirms that OT-SI (i.e., occupational therapy using sensory integration) is effective” [16].

Other studies followed, reaching similar conclusions, and added clarification to the efficacy of using sensory strategies outside the therapy session and employed by teachers in general education classrooms [13,17-21]. Even so, many educators, observing the work of therapist interacting with students from their classrooms, adopted the strategies employed by trained occupational therapists for global use in their classrooms [12]. Teachers adopted the use of stationary stability balls as a replacement for traditional chairs as one sensory strategy they believe affects inattention [12]. Because identification of ADHD continues and is a growing concern in many classrooms, many teachers continually search for effective strategies to employ when working with these so students in the general education classroom.

The research supporting the use of sensory techniques, such as the use of stationary stability balls in place of traditional chairs, appeared somewhat confusing based upon the inconsistent data emerging from the limited research conducted [10]. In an era of high stakes testing, schools must promote valid methods in the classroom setting for students to demonstrate proficient performance in academic learning (Learner & Johns, 2012). The recommendations of many studies on the topic of sensory integration and the efficacy of sensory integration therapy call for continued research in this area (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000). Therefore, by examining the direct effect of sitting on a stationary stability ball for students currently identified as exhibiting issues with inattention, this study adds to the body of work conducted in the past and currently underway in the field of developmental disabilities related to the efficacy of sensory integration approaches.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to examine the effect of sitting on a stationary stability ball versus a traditional classroom chair in a structured learning activity in the regular education classroom for students identified as experiencing concerns for inattention due to ADHD.

Method

Participants

Four students, two girls and two boys, from a local elementary school participated in the study. The elementary school serves 751 PreK- 5th grade students with a student-teacher ratio of 18 to 1. Twenty-eight percent of students qualify for free and reduced lunch. The school district served just over 400 students with disabilities, PreK – grade 12, or 15.87% of their student population. The students identified for this study received a determination of ADHD through the school district’s process of eligibility determination for special education.

Human Subjects and Informed Consent

The study obtained Human Subjects approval from the University and the school district where the research was conducted. Prior to any data collection, parental consent and student assent were obtained. Student assent was obtained by discontinuing the prompting procedures if students physically resisted or stated no to the session’s activities.

Setting

The research study was conducted in a regular classroom setting. Participants attended a typical 3rd grade classroom. The 3rd grade classroom in which the study occurred consisted of one teacher and 25 students. There were 13 boys and 12 girls. The classroom schedule included instructional activities such as: writing in a journal, correcting grammar and punctuation in sample sentences written on the board, reading and math lessons, social studies and science activities, recess and lunch, curricular specials (e.g., art, music, physical education, etc.), and other required academic and management tasks. Instruction was provided with opportunities for both whole group and small group or individual work times. For instance, formal, whole group instruction in reading basic skills becomes less of the focus of instruction starting at this grade level as students move from learning to read to reading to reading to learn. Math instruction was often taught in some form of whole group instruction followed by opportunities for individual practice and small group supplementary instruction.

Dependent Measures

The dependent variable was identified as the percentage spent on task compared to off task for each participating student. A student demonstrates task behavior when he/she is attentive to the teacher’s presentation of lesson materials and directions. The student looks at the teacher and other students when they are talking and follows along in the lesson and discussion. The student sits quietly in his/her chair without excessive extraneous movement that interferes with attention. Student’s verbal expressions are on target with class discussion and contribute to their and other student’s learning. Data analysis in single-subject designs use data that is collected and presented graphically [22]. Throughout the study, students were observed in the regular classroom environment. The primary researcher collected and recorded the data related to on-task behavior within the general education classroom. A partial interval data collection procedure was used to record on and off task behavior [23]. Partial interval recording involves observing whether the behavior occurs or does not occur during specific time periods. In this study, the length of the observation session was identified as 45 minutes in length or the entire math period. The observer used a clock with a second hand while observing the student. At the end of every 15 second interval, the observer looked at the students and recorded whether the students were on task (+) or off task (-) and recorded it on the data sheet. This type of time sampling in a classroom setting provided an unobtrusive method for observing student’s behavior. An interval form of data collection was selected for this study because the goal of the study was to observe increases or decreases in attention due to the intervention. Data from the interval recordings was converted into percentages [23-25]. The total number of observations divided by the number of plusses recorded yielded the percentage of time the students were ontask. The total number of observations divided by the number of minuses recorded yielded the percentage of time the students were off task. The percentages yielded by the observations equaled 1005 and were used to predict the level of attention for the whole instructional period and for similar instruction activities that may occur throughout the day when the students were not observed. The interval recording method of data collection has been proven an effective method of observing data [26].

Interobserver Agreement/Reliability

Interobserver agreement, or interrater reliability as it is sometimes called, refers to the extent to which the data collected by two individuals observing the same student behavior agrees [27]. Inter-observer agreement was used to increase confidence in the data achieved when observing the subjects. The primary researcher and another, trained observer, both observe the same behavior independently and then compare their data. If the data appeared the same, then it was considered reliable [16]. The primary observer in this study was the researcher. The independent observer was a retired educator who was experienced in observing students in an educational setting. The researcher trained the independent observer on the use of the observation form and procedures for collecting the data prior to implementation of the study. Training consisted of explanations and practices of the data collection procedures. The researcher gave a clear description of on and off task behavior and an understanding of the research questions. The independent observer was provided with an opportunity to ask questions and to practice completing the data tracking form using a video of students in a classroom setting provided by the researcher.

To ensure that a reliable measurement procedure was present, the researcher and the independent observer separately watched the video and completed the observation form on the same student. The independent observer observed 20% of the scheduled observations. The primary researcher selected sessions for the independent observed based on the school schedule and her availability. Session by session reliability was obtained through comparing the researchers and the independent observer’s recorded data. The researcher and the independent observer used the data collection procedures for each session. The interval-by-interval comparison of the data was then used to determine whether there was agreement for each individual interval. The comparison of agreements was then recorded on a separate interobserver agreement data collection form. Interobserver reliability was calculated by dividing the total number of agreements (when looking at total number of times observers agreed versus not agreed) compared per interval across all intervals for an individual session and multiplying this by 100 to get a percentage of agreement. The percentages were then added together across all the sessions that were compared and divided by the total number of sessions to determine a percentage of overall interobserver agreement between the primary researcher and the independent observer. Seventy percent reliability was used to constitute a minimum criterion for inter observer reliability/ agreement [25]. Reliability did not fall below 70%, so no retraining was needed throughout the course of the intervention period.

Number of Session-By-Session Agreement Scores Between Primary Observer and Independent Observer (on-task total) x 100 = % of reliability

Interobserver Agreement Scores Between Primary Observer and Independent Observer (on-task total) for individual students.

The agreement scores from the comparison of the primary research and independent observer were 96%. The overall results of interobserver agreement/reliability for the baseline sessions varied from 80% to 95% agreement. Intervention sessions agreement scores ranged from 80% to 94% agreement.

Social Validity Measures

At the conclusion of the study, all four students and the teacher in the classroom where the study took place were interviewed to solicit their opinions about the intervention. The questionnaire consisted of six questions related to the implementer’s opinion of the stationary therapy balls procedure for improving school performance. Specifically, the survey asked questions regarding perceived effective stationary balls on on-task behavior of the participants, the effects related to the performance of other school related behaviors, ease of intervention implementation, and overall beliefs related to the usefulness of the stationary ball intervention procedure. Respondents selected from five Likert Scale options of (5) strongly agree, (4) agree, (3) neither agree or disagree, (2) disagree, or (1) strongly disagree. Results of the survey indicate the high level of user satisfaction with the stationary ball intervention as a method improving school behavior, especially on-task behavior.

All four participants participated in an interview. The four students indicated that they did not exhibit any concerns about participating in the study. When asked if they were concerned about what other students might say if they knew they were participating in the study, all four students said they were not concerned. The students also said that they felt they stayed ontask better when sitting on the stationary stability ball. When asked what their perspectives were about participating in the study, being observed, and using the stationary stability balls, all four students indicated that they did not have concerns about using the balls to sit on in the classroom. Roger indicated that he thought it might be fun to sit on the stationary stability balls. Mary asked if she would get to pick which ball, she sat on when used in the classroom. Following the study, students were interviewed and asked their perspective related to participating in the study. Students did not express any concerns after participating in the study. All the students said that they liked sitting on the stationary stability balls the most because they could move around. The results of the social satisfaction interviews appeared ironic since the students commented on liking the ability to bounce and move on the balls and that it was fun. The irony with these statements was that the stability balls were theoretically meant to improve the on-task behavior and decrease the physical inattention, when the comments from the students appeared to infer that the stability balls produced the opposite effect. Three of the four students, John, Alice and Mary, indicated that they thought they performed better when seated on the stationary stability ball.

The classroom teacher was also interviewed at the conclusion of the study. When asked why she was interested in the study she indicated that she was concerned with the number of students in her classroom for whom attention was a concern and wanted to provide them with the best opportunity to participate by using strategies that reduce problems with attention. When asked about any impact the study may have on her students or on herself, she responded that the students in her class were used to other adults coming and going, as was she, and she did not express concerns in this area. The only concern the teacher expressed about the study was the potential for disappointment if the study revealed that the stationary stability balls were ineffective as a strategy to use with students. She personally believed they were beneficial. Regarding the students’ level of attention during the study, the teacher expressed that the students’ performance during the baseline observations appeared consistent with their overall performance during other instructional times and prior to the study starting. She indicated that she believed that the students managed switching from baseline to intervention well. The students did not express any concerns to her about participation in the study prior to or during the study.

Experimental Design

The experimental design used in the study included a single subject ABAB multiple baseline design. The independent variables included sitting on a stationary stability ball and sitting on a traditional classroom chair. The dependent variables included attention to task – whether the students were attentive to instruction or inattentive to instruction. In other words, the study was conducted to determine if the independent variable (type of chair/seating) influenced attention to instruction and whether the students were more attentive or less attentive based on the type of seating used. Single subject research is an appropriate method for this study because of the small sample size. Single subject research is also useful to study changes that occur when a treatment is applied to behavior, in this case the effect of chair type on attention. Single subject research has its roots in clinical settings but are useful in educational settings when studying student behavior [22]. An ABAB, reversal design was used to examine whether the intervention (sitting on a stationary stability ball) improved attention. When working with students, an ABAB design overcomes concerns for other types of single subject designs in that it ends with the treatment phase, thus appearing more ethical than an ABA design which ends with the treatment effect removed [22,23,26]. According to Gay et al. [22], if the treatment effects are the same during both phases of treatment, the possibility of influences from extraneous variables is reduced. The design also strengthens the conclusions drawn from the study by introducing the treatment twice. An ABAB or reversal design also allows for greater consideration of generalization of findings to other settings.

The students were observed during a baseline condition (A1). Condition A1 involved the students sitting on a traditional classroom chair during classroom instruction. Following A1, the independent variable was introduced. The independent variable included the introduction of a stationary stability ball for use in place of the traditional classroom chair - Condition B1. In a reversal design, the subjects are observed in the baseline condition (A1), then observed in a treatment condition (B1), returned to the baseline condition (A2) again, followed by the treatment condition (B2). Using a reversal design of this nature allows the researcher to see if introducing the independent variable causes changes in the dependent variable [23,25].

Procedures

The independent variables consisted of the use of a stationary stability ball versus a traditional classroom chair. Observations occurred during a structured, whole class lesson in the general education classroom environment. In this study, the length of the observation session included the whole math period. Observations were separated into 15-second intervals for observation and recording of the presence or absence of on-task behavior by the participating students.

General Procedures: The student’s performance was observed over the course of eight weeks, with a minimum of four observations per week. The researcher worked with the classroom teachers to determine the best opportunity to observe attention during a whole class activity that required focused attention on teacher instruction. Math class was selected, and a beginning date determined.

Baseline Procedures: The baseline condition, A1 and A2, involved observing students while they were seated on the traditional classroom chair. No specific instruction was required for students during the initial baseline phase. Intervention Procedures: Following A1, the traditional chairs were replaced with stationary stability balls. This change in seating is B1 of the study. The classroom teacher had provided the students with a brief instruction on the proper use of the stationary stability balls prior to the study starting. Students were told they needed to sit on their bottom with their feet on the floor. Non-examples of improper sitting were also provided. For example, sitting on the knees and laying across the ball on the stomach or back were not allowed for safety reasons. During observations, students who demonstrated non-example types of sitting or requiring redirection were considered off-task.

Results

Overall Results Related to On-Task Behavior

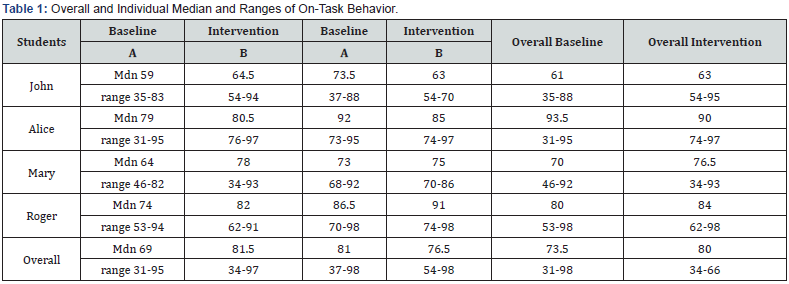

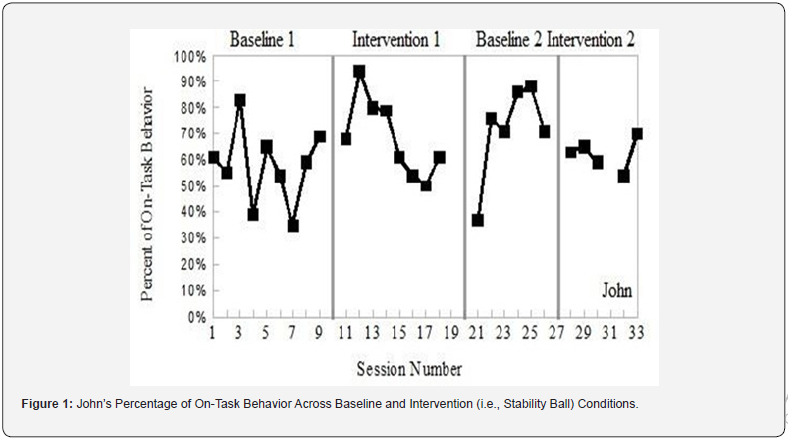

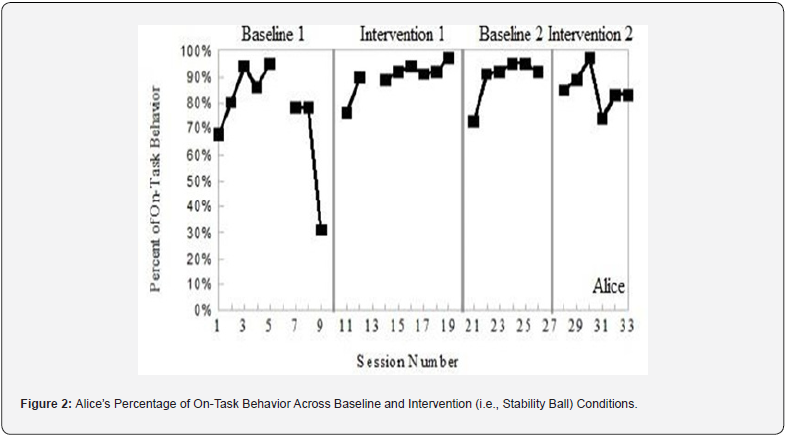

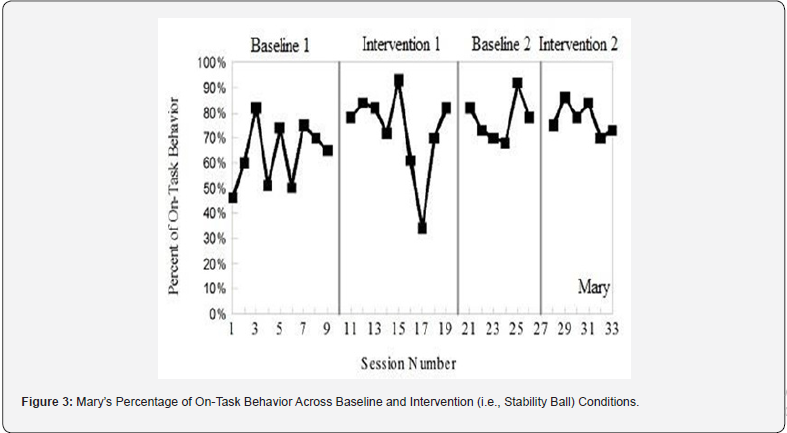

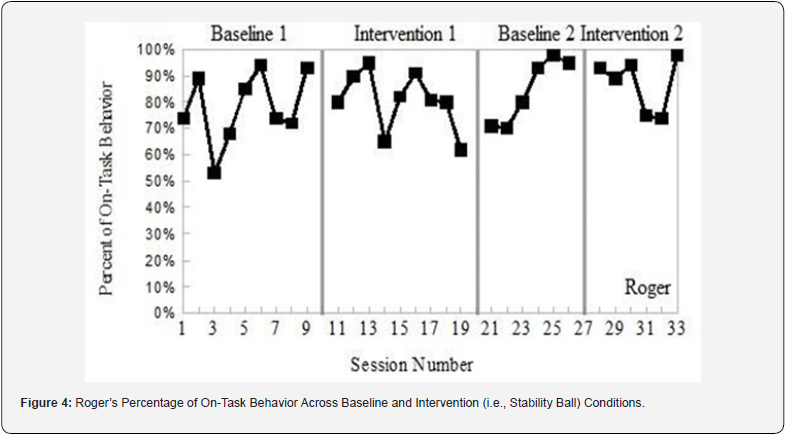

The data in Table 1 and from individual data from Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4 indicate that the intervention, sitting on the stationary stability ball, showed negligible effective across time when used to improve student on-task behavior. The overall median percentage of intervals of on-task behavior for all 4 participants during the initial baseline (i.e., Baseline A1 - stitting on standard classroom chairs) was 74.5%, with the overall range for the percentage of intervals from 54 to 81 for on-task behavior. The overall median percentage of intervals of on-task behavior for all 4 participants during the initial intervention (i.e., Intervention B1 – sitting on stationary stability balls) was 78.5%, with the overall range for the percentage of intervals from 69 to 87 for on-task behavior. The overall median percentage of intervals of on-task behavior for all four participants during the second baseline (i.e., Baseline A2 - sitting on standard classroom chairs) was 80.5%, with an overall range for the percentage of intervals from 64 to 91% for on-task behavior during this condition. The overall median percentage of intervals of on-task behavior for all 4 participants during the second intervention (i.e., Intervention B2 - sitting on stationary stability balls) was 82%, with an overall range for the percentage of intervals from 64 to 89% for on-task behavior during this condition. See Table 1 for individual scores for the median and ranges for the percentage of intervals of on-task behavior for each student scores across all experimental conditions.

John’s On-Task Behavior. The data in Figure 1 indicated that John’s on-task behavior varied throughout the study with a negligible improvement related to on-task behavior with the use of the stationary stability ball intervention (see Table 1 for a summary of medians and ranges across interventions for individual participants). John’s overall attention to teacher instruction and classroom discussion remained consistently low regardless of the type of seat he used. The difference in attention between baseline and intervention appeared negligible. Due to the overlap in data paths when comparing baseline measures to the implementation of on-task behavior during the use of the stability balls, the data did not exhibit the necessary differential effects to show potential effectiveness for improvements of ontask behavior with John. Alice’s On-Task Behavior. The data in Figure 2 and Table 1 indicated that Alice’s on- task behavior was quite steady with a very slight decrease in attention with the use of a stationary stability ball intervention. The differential effects of the use of a stability ball when compared to the use of a standard classroom chair (i.e., baseline) for improving on-task behavior were not evident with Alice. The excessive overlap in data when comparing the baseline to the use of stability balls for improving on-task behavior preclude the determination that a functional relationship exists due to the implementation of the stability balls when compared to baseline conditions.

Mary’s On-Task Behavior. The data in Figure 3 and Table 1 indicated that Mary’s on- task behavior improved slightly with the use of a stationary stability ball intervention. Unfortunately, the amount of overlapping data between the data paths in baseline and when using the stability balls interferes with affirming that a slight improvement was due to the introduction of the stability balls as related to improvements in on-task behavior. Therefore, the slight improvements for Mary related to on-task behavior appear inconsequential and prevent the affirmation of the consequent [23,25,26] that improvements in behavior were due to the use of the stability balls and not some other unaccounted-for variables. Roger’s On-Task Behavior. The data in Figure 4 and Table 1 indicated that Roger’s on- task behavior improved slightly with the use of a stationary stability ball intervention. Unfortunately, Roger’s data also display a great deal of overlap when comparing the baseline to the use of the stability ball intervention. This overlap in data and lack of differential effects across experimental conditions prevents the conclusion that the use of the stability ball intervention was effective for the improvements in Roger’s on-task behavior. At best, the data from Roger and the rest of the students participating in the study was inconclusive related to improving the on-task behavior of the participants. In other words, the use of stability balls for improving the school-based performance of these students in this general education setting was not effective.

Discussion

The study was proposed because of the growing number of students identified as exhibiting ADHD [10]. To meet the needs of these students, classroom teachers often employ strategies that are not founded in empirical research [27]. Research about the effectiveness of using stationary stability balls with students who struggle with inattention was based on theories about sensory integration and sensory integration therapy. A review of literature indicated that previous studies yielded inconsistent findings [16]. Three of the four students participating in the study demonstrated a slight but negligible improvement in attention when comparing the use of a traditional classroom chair to a stationary stability ball. John demonstrated a slight decrease in inattention from baseline to intervention. Alice, Mary, and Roger all demonstrated a slight but negligible increase in attention from baseline to intervention. In examining the data for all four students, over the course of the entire study, the results were negligible from baseline to intervention.

The results from this study suggest that using stationary stability balls to improve attention for students with ADHD neither helped nor hindered their ability to attend to and learn from classroom instruction. The study adds to the body of work that presents inconsistent findings with only a few studies supporting the use of stationary stability balls as a means of impacting attention. When considering strategies based on understandings and theories on sensory integration, this study confirms what other studies found - there was not enough evidence to support the use of stationary stability balls for improving attention [16]. If one perceives attention as a proxy for learning, results also indicated that there was not enough evidence to support the use of stationary stability balls for improving learning in this general education setting. Numerous previous studies addressing the link between sensory therapy and improved attention did not successfully link sensory integration approaches to improved attention [19] in this study. May-Benson and Koomer [21] reviewed 27 studies related to this topic. Their overall impression included that a sensory integration approach may result in better outcomes than no intervention at all, although that small improvement often appeared negligible [21]. Fedewa et al. [27] conducted a study specifically looking at the use of stationary stability balls to increase attention. They found similar levels of on-task behavior and achievement in both a control group and treatment group of students in a general education setting refuting the effectiveness of the use of stationary stability balls in the classroom [28].

In contrast, Ketcham and Burgoyne [29] conducted an observational study similar in scope to this study. They observed in an elementary classroom that already implemented stationary stability balls as a seating option for students. They reported a 10% decrease in movement for students when seated on a ball versus classroom chair [29]. Because of the inconsistent findings of previous studies Wu et al. [30] conducted a study using electroencephalograms (EEG) to measure attention to tasks when seated on a chair versus a stationary stability ball. Their findings indicated that there was no difference in reaction time and attention for students with ADHD and typical peers while seated on balls [30].

When preparing a study, it is important to control as many extraneous variables as possible confounds with outcomes of the study. There are a host of variables in educational settings that are not accounted for that can influence the outcome of the study. One needs to consider the host of limitations inherent in a classroom setting that are totally out of the students’ and teacher’s control. Researchers should watch and control for these variables as much as possible. While researchers may draw conclusions from studies despite potential cofounding variables, it is important to account for those flaws when reporting results [24,31]. Some of the limitations in this study were as follows: the differential effects of the characteristics of ADHD with each student; how the characteristics of this disorder influenced their learning outcomes; the setting, curriculum, level of distractibility, behavior of peers, classroom management approaches in the classroom; unexpected interruptions in schedules, such as substitute teachers or impromptu meetings between the teacher, principal, or a parent; or other unexpected health concerns in the classroom, such as a student with a loose tooth. These potential influences need careful consideration when interpreting the results of the study. Although research conducted in this area resulted in negligible findings, continued attempts at validating sensory integration strategies appear warranted. General education teachers need to continue to use research-based approaches in their classrooms with students and to become knowledgeable about what strategies are found effective based on empirical research [32].

Summary and Conclusions

The purpose of this research study was to examine the effect of sitting on a stationary stability ball versus a traditional classroom chair in a structured learning activity in the regular classroom for students identified as experiencing concerns for inattention due to ADHD. The data was analyzed using an ABAB, single subject research design. The results from this study suggest that using stationary stability balls to improve attention for students with ADHD did not appear to increase student’s ability to attend to and learn from classroom instruction. The research adds to the body of work previously conducted analyzing the use of sensory integrative techniques, such as sitting on a stationary stability ball, for use with students with ADHD to improve attention.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2023) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision: DSM-V-TR (5th ). Washington, DC.

- Friedman-Hill S, Wagman MR, Gex SE, Pine DS, Leibenluft E (2011) Researchers at National Institute of Mental Health target cognition. Psychol & Psychiatr J 115: 93-100.

- Goldman LS, Genel M, Bezman R (1998) Diagnosis and treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of American Medical Association, 279(14): 1100-1107.

- Loe IM, Feldman HM (2007) Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(6): 643-654.

- Portilla XA, Ballard PJ, Adler NE, Boyce WT, Obradovic J (2014) An integrative view of school functioning: Transactions between self-regulation, school engagement, and teacher-child relationship quality. Child Dev 85(5): 1915-1931.

- Merrell C, Tymms PB (2001) Inattention, hyperactivity and impulsiveness: Their impact on academic achievement and progress. Br J Educat Psychol 71(1): 43-56.

- Pingault J, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Carbonneau R, Genolini C, et al. (2011) Childhood trajectories of inattention and hyperactivity and prediction of educational attainment in early adulthood: A 16-year longitudinal population-based study. Am J Psychiatr 168(11): 1164-1170.

- Rader R, McCauley L, Callen EC (2009) Current strategies on the diagnosis and treatment of childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am Family Phys 79(8): 57-65.

- Antshel KM, Hargrave TM, Simonescu M, Prashant K, Hendricks K, et al. (2011) Advances in understanding and treating ADHD. Bimed Central Med 72(9).

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009) Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The NICE guideline on diagnosis and management of ADHD in children, young people, and adults. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. British Psychological Society.

- Pelham WE, Wheeler T, Chronis A (1998) Empirically supported psychosocial treatments for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Psychol 27(2): 190-205.

- Jacobson JW, Foxx RM, Mulick JA (2005) Controversial therapies for developmental disabilities: Fad, fashion, and science in professional practice. L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Vargas S, Camilli G (1999) A meta-analysis of research on sensory integration treatment. Am J Occup Therap 53(2): 189-198.

- Kranowitz CS (2005) The out of sync child (2nd). Berkley Publishing Group.

- Dunn W (2001) The sensations of everyday life: Empirical theoretical, and pragmatic considerations. The American J Occup Therapy 55(6): 608-619.

- Miller LJ, Schoen SA, James K, Schaaf RC (2007) Lessons learned: A pilot study on occupational therapy effectiveness for children with sensory modulation disorder. Am J Occup Therap 61(2): 161-168.

- Devlin S, Healy O, Leader G, Hughes BM (2011) Comparison of behavioral intervention and sensory-integration therapy in the treatment of challenging behavior. J Autism Dev Disord 41(10): 1303-1320.

- Hoehn TP, Baumeister AA (1994) A critique of the application of sensory integration therapy to children with learning disabilities. J Learn Disabil 27(6): 338- 350.

- Humphries T, Wright M, Snider L, Mcdougall B (1992) A Comparison of the effectiveness of sensory integrative therapy and perceptual-motor training in treating children with learning disabilities. J Dev Behav Pediatr 13(1): 31-40.

- Koenig K, Huecker G, Kinnealey M (2005) Comparative outcomes of children with ADHD: Treatment versus delayed treatment control condition. American Occupational Therapy Association Annual Conference and Exposition, Long Beach, California.

- May-Benson TA, Koomer JA (2010) Systematic review of research evidence examining the effectiveness of interventions using a sensory integrative approach for children. Am J Occup Therap 64(3): 403-414.

- Gay LR, Mills GE, Airasian P (2012) Educational research: Competencies for analysis and application. Pearson Education, Inc.

- Cooper JO, Heward WL, Heron TE (2020) Applied behavior analysis (3rd). Pearson Education, Inc.

- Alberto PA, Troutman AC, Ax JB (2022) Applied behavior analysis for teachers. (10th edn). Pearson: Merrill/Prentice Hall Publishing.

- Johnson JM, Pennypacer HS (2009) Strategies and tactics of behavioral research (3rd). Routledge Publishing.

- Kazdin A (2011) Single-Case Research Design. Oxford University Press, Inc.

- Marques JFK, McCall C (2005) The application of interrater reliability as a solidification instrument in a phenomenological study. The Qualitative Report 10(3): 439-462.

- Fedewa A, Davis MA, Ahn S (2015) Effects of stability balls on children’s on-task behavior, academic achievement, and discipline referrals: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Occup Therap 69(2): 1-9.

- Ketcham CJ, Burgoyne ME (2015) Observation of classroom performance using therapy balls as a substitute for chairs in elementary school children. Journal of Education and Training Studies 3(4): 42-48.

- Wu W, Wang C, Chen C, Lai C, Yang P, et al. (2012) Influence of therapy ball seats on attentional ability in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Phys Therap Sci 24(11): 1177-1182.

- Brown G, Wack M (1999) The difference frenzy and matching buckshot with buckshot. The Technology Source, May/June1999, University of North Carolina.

- McLeod SA (2007) What is reliability?