Whole-Foods, Plant-Based Diet Alleviates the Symptoms of Fibromyalgia

Anna C Clifton, Chelsea M Clinton, Billy Zhang, Mary R Clifton* and Colleen M Renier

Michigan State University, USA

Submission: October 28, 2017; Published: November 21, 2017

*Corresponding author: Mary R Clifton, Michigan State University, America's Holistic Telemedicine Doctor, 5 th Avenue, New York City, USA, Email: marywendtmd@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Anna C C, Chelsea M C, Billy Z, Mary R C, Colleen M R. Whole-Foods, Plant-Based Diet Alleviates the Symptoms of Fibromyalgia. Nov Tech Arthritis Bone Res. 2017; 2(2) : 555584.DOI:10.19080/NTAB.2017.02.555584

Abstract

Objective: To determine if a vegan diet will result in subjective reduction in perceived pain and functional limitations.

Methods: This was a six-week randomized controlled study of participants aged 18-70 with an official diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Participants were randomized to a whole-foods, plant-based diet (WFPB) or to continue their current diet. Outcomes were assessed by mixed model analysis of a weekly 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36v2), weekly Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) scale, and weekly Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain assessments. Mixed model analysis evaluated changes from baseline of the following clinical measures: weight, BMI, body temperature, pulse, and blood pressure.

Results: 40 Participants were randomized. 39 of them, 19 control and 20 intervention, completed the study. Throughout the six-week study, the intervention group reported a significantly greater improvement than the control group in SF-36v2 energy/vitality, physical functioning, role physical, and the physical component summary scale in physical functioning (PF), energy/vitality (VT), physical component summary scale (PCS), mental health (MH); p values varied between <0.05 to <0.001. Differences between the intervention and control PGIC scales were statistically significant towards the conclusion of the study (p < 0.05), with the intervention groups showing a more pronounced decrease. Intervention group improvement in weekly mean VAS assessments was also significantly greater (p < 0.01) than that of the control group from weeks two through five.

Conclusion: A whole-foods, plant-based diet significantly improves various aspects self-assessed measures of functional status among fibromyalgia patients

Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a medical disorder characterized by widespread chronic pain, difficulty sleeping, daytime fatigue, sleepiness or somnolence, and an inappropriate response to pressure stimuli. With an estimated prevalence of 1-2% and female to male ratio of approximately 7:1, Fibromyalgia's etiology remains unclear, but research suggests that central nervous system abnormalities including sensitization of neural circuits and impaired descending inhibitory pain pathways contribute to fibromyalgia's symptomatology [1].

Unfortunately, side effect profiles of many medications used to treat fibromyalgia can deter patients from compliance. It is also thought that medications alone may not be a comprehensive enough approach to alleviate symptoms in this complicated condition. Therefore, non-pharmacological therapy including dietary modifications should be incorporated into treatment. In fact, this has already been shown to improve symptoms in patients with many other chronic conditions [2]. The American Dietetic Association (ADA) further supports this position that appropriately planned vegetarian or total vegetarian/vegan diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases [3]. In fact, vegans have increased levels of beta and alfa carotenes, lycopenes and lutein, and vitamin C and E in their sera [4], which is important because of their role as antioxidants. Vegan diets are also low in arachidonic acid, a precursor to inflammatory prostaglandins, which is increased in the western diet [5-9].

Studies investigating the effect of dietary modification on fibromyalgia symptoms have been promising. One open, nonrandomized controlled study of 33 patients found beneficial effects of a vegan diet on fibromyalgia symptoms in a three- month intervention period, with improvements in the Visual Analog Scale and three other scales [10]. An observational study of 30 fibromyalgia patients on a raw vegetarian diet with daily supplementation of dehydrated barley grass juice showed benefit in 19 of the participants. Short-form Health Survey (SF- 36) measures for all scales except bodily pain were no longer statistically different from baseline for women 45 to 54 years of age in this group of 19 responders [11-18]. The beneficial effects of WFPB diets on mood and depression are reported in previous studies [19-22], including a 2016 cross-sectional study that observed dietary habits of patients with fibromyalgia and found that patients who ate at least daily or nearly daily fruit and fish had improved scores on depression and outlook on life. However, there have been no published randomized controlled trials assessing whether a vegan diet including cooked and uncooked food and gluten-containing foods would benefit fibromyalgia patients.

Purpose

The specific aim of this study is to determine if a WFPB diet will result in a subjective reduction in perceived pain and functional limitation in patients suffering from fibromyalgia. The following are hypothesized

i. Improvement in the SF-36v2 BP, PF, RP, VT, and PCS will be significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group.

ii. Among participants capable of experiencing a clinically important level of change in VAS (>1.3), i.e those with a day 1 VAS >2, VAS improvement will be significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group.

iii. PGIC scale improvement will be significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group.

Methods

This study was a 6-week randomized controlled trial. The Institutional Review Board approved the clinical study site and protocol. All patients provided written informed consent before the commencement of any study activities or protocols.

Subjects

The subjects were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: male or female patients aged 19 to 70 years at the start of the study. A physician must have diagnosed each patient with fibromyalgia. Patients were also deemed capable of buying and preparing their meals. Patients were discouraged to significantly modify their pain management regimens, but the patient's provider could modify other medications as needed. Patients that were illiterate, visually impaired, non-English speaking, diabetic, following a prescribed diet, pregnant, diagnosed with eating disorder, already vegetarian or vegan, or with known food allergies were excluded from this study. Patients were recruited through local physician offices, a local fibromyalgia support group, local newspaper, and www.drmarymd.com, the website of Dr. Mary Clifton, and their eligibility was screened by phone. Eligible patients were emailed or mailed a copy of the informed consent to read. If patients were still interested after receiving a copy of the informed consent, patients were formally consented at Dr. Clifton's office. Patients were randomized into the control or intervention group using randomization blocks of four and trained through the use of a one hour presentation on plant- based diets.

They were also directed to www.pcrm.org and www. drmarymd.com for low glycemic, animal free, low fat food options, given a vegetarian starter kit, and 21 days of vegan recipes from the Physician's Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM). The control group continued their normal omnivorous diet program. Twenty-four hour food recalls were obtained at the start and end of the trial, and once a week for the six weeks of the trial via telephone. Patients underwent a final interview at the end of the six-week study period. Patients received additional individual consultation as needed to promote compliance and answer specific questions. Over the six weeks, the Patient Global Improvement of Change (PGIC) and the MOS 36 item short form health survey (SF-36) were performed weekly by telephone. Patients performed a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) of their daily pain level daily at home. C-reactive protein levels were assessed at the beginning and end of the study at Munson Medical Center Laboratories as a secondary measure of diet changes and inflammatory status.

Analysis

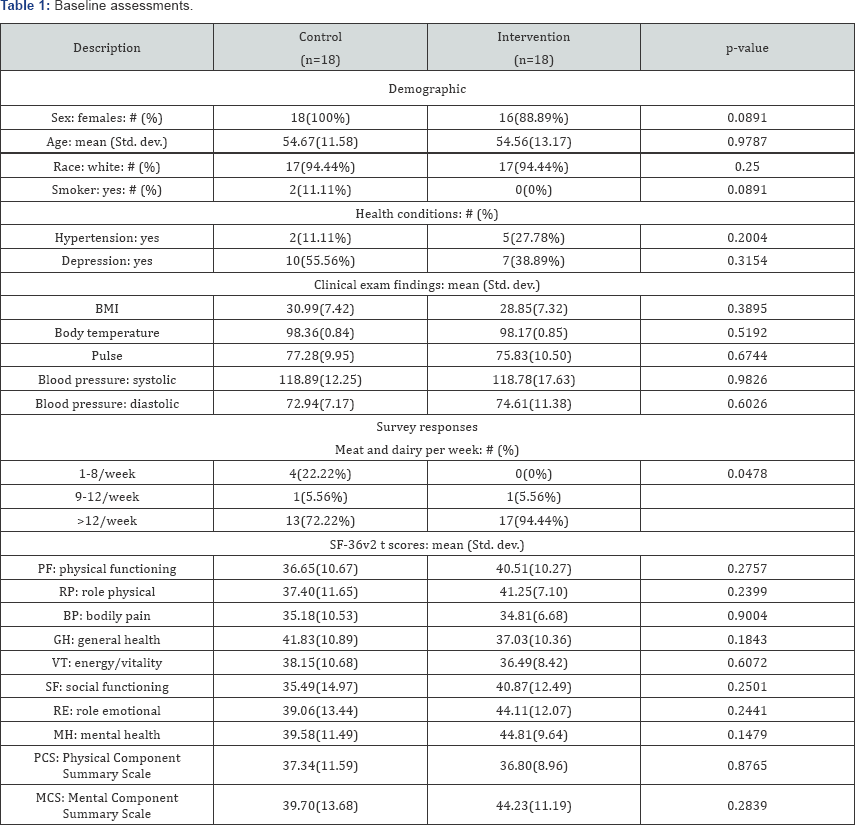

Baseline Assessment: Summary statistics were calculated from baseline assessments table in Table 1. The quantitative date was expressed as the mean (SD) and nominal data was expressed as the number (percentage). Comparability between the control and intervention groups was calculated using student’s t-test (two-tailed), nominal data compared by Fisher's exact test (two-tailed), and nominal data greater than two categories was calculated using chi-squared test. Statistical significance was defined as a p value less than 0.05.

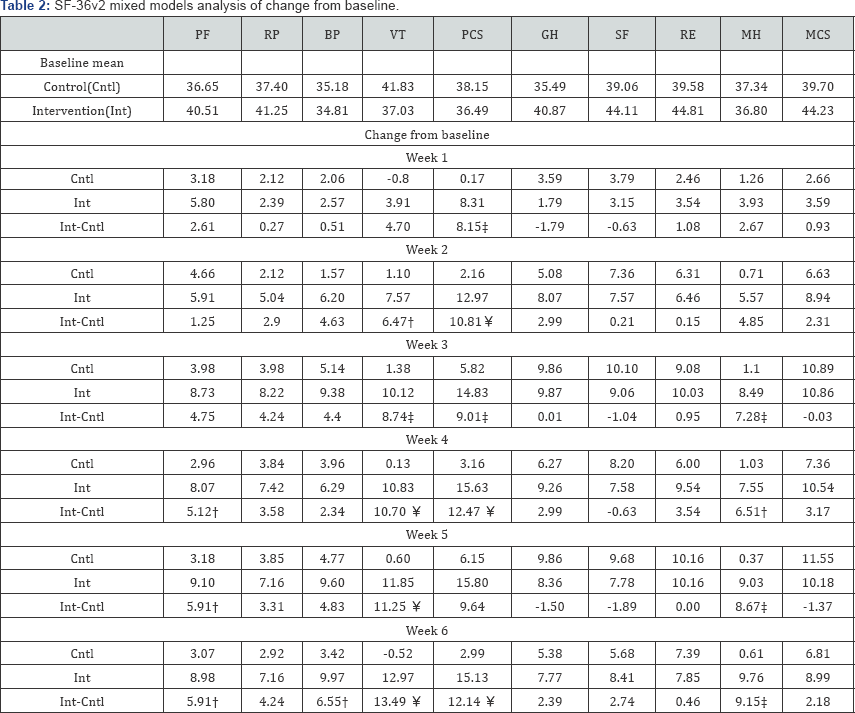

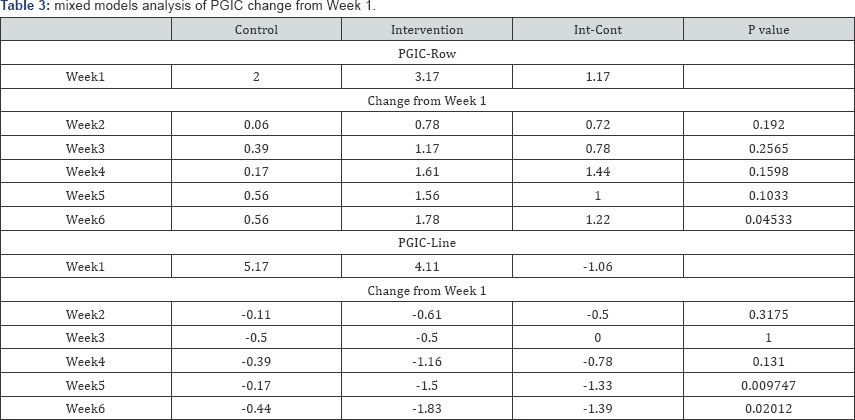

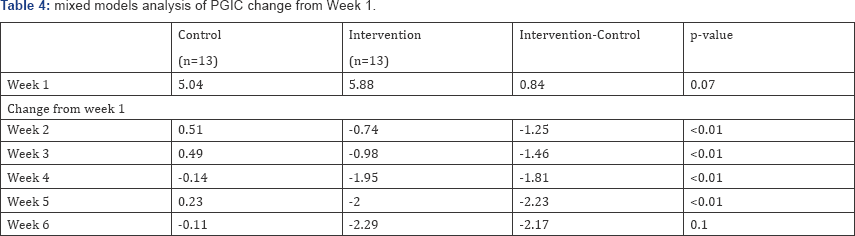

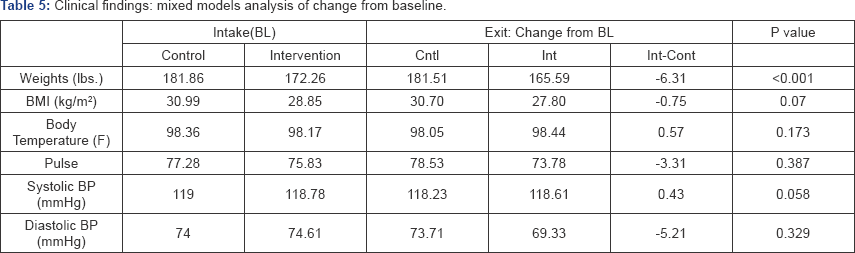

Primary outcomes: The primary outcome variables were changes in pain and functional status between the first and last week of the study, as measured by the SF-36v2 domain subscales for bodily pain (BP), physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), energy/vitality (VT) and Physical Component Summary (PCS) scores, VAS, and the PGIC scales. Mixed models (repeated measures) analysis was used to evaluate change in SF- 36v2 subscales from intake baseline level (BL) and determine if the difference in change between the intervention and control groups was statistically significant (Table 2). Additional mixed models analysis of PGIC-Row and PGIC-Line data was conducted to evaluate description of life changes related to pain and rating of degree of change since baseline level. Because the PGIC measures change associated with participant's baseline pain and the VAS was not measured at intake, the participant's BL SF-36v2 BP subscale score was included as a covariate in analysis of PGIC- Row and PGIC-Line (Table 3). VAS data, which was only available for a subset of participants, was evaluated for participants with a VAS of 2 or greater on Day 1. Mixed models analysis compared mean weekly VAS data to evaluate statistical significance (Table 4). It was also used to determine if any changes to clinical findings had significantly changed from baseline (Table 5).

Results

Baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and surveys

The majority of study participants were female (94.5%) and average age was 54 years old. No statistically significant demographic or clinical diagnoses were identified at intake. Survey responses showed a significant difference in the frequency of meat and dairy ingested per week between 1-8 times. No statistically significance difference was noted at 9-12 or >12 times of meat and dairy ingestion per week (Table 1).

Efficacy

The primary focus of the SF-36v2 analysis was the four domains and single component summary scale previously identified as directly related to pain and functional limitations: BP, PF, RP, VT, and PCS (Table 2). PF was statistically significant in weeks 4 to 6 (p <0.05). VT was significant in week 3 through week 6. PCS demonstrated less consistent findings. Significance was found beginning in the first week until week 4. No difference was noted in week 5, but again noted to be significant in week 6. RP, BP, GH, SF, RE, and MCS did not show any significant differences. However, MH consistently showed a significant difference in weeks 3-6. None of the SF-36v2 measures had any findings of statistical significance through the six-week study period.

Mean weekly PGIC-row (description of change related to pain) and PGIC-line (degree of change since beginning) scores, adjusted for SF-36v2 BP at BL, are shown in Table 3. No statistical significance between intervention-control differences existed in either scale during week 1 of the study, with PGIC- row means between 3.0 and 2.0, respectively, and PGIC-line means at 5.0 (no change) and 4, for intervention-control group, respectively. In the PGIC-row group, statistical significance was seen only in week 6. No differences were calculated in weeks 1 through 5. There was a consistent increase in the PGIC-row intervention group when compared to the control group, however, only significance was seen at week 6. In week 2, PGIC-row control group increased to 2.06, while the intervention group jumped to around 4.0. By the completion of the six-week trial, the intervention group scored close to 5.0 and the control group barely surpassed 2.5. In the PGIC-line group, statistical significance was calculated in week 5 and 6, but no statistical significance was noted in weeks 1 through 4. Control group PGIC-line means minimally varied over the 6 weeks of the study, while intervention group means decreased steadily over time, from 4.11 to 1.83 on a scale where 5 = "no change" and 0 = "much better."

Table 4 illustrates the mixed models (repeated measure) analysis evaluating change in mean VAS assessments from Week 1. When compared to the results of the baseline, the VAS scores were significantly improved. These changes and improvements were consistent through weeks 2-5 (Table 4). However, there was no significance in the final week of the study. Participants were asked to provide a VAS assessment each day at a random time and a subset of participants, 13 controls and 13 interventions, provided the requested data. To be able to assess clinically important change in VAS, analysis was restricted to participants with a day 1 VAS of 2 or more.

Table 5 depicts changes in clinical findings from intake baseline to exit. The average weight loss between the control and intervention groups was statistically significant. With the decrease in weight loss, there was also an associated decrease in BMI. No significant changes in body temperature, pulse, and systolic or diastolic blood pressure were noted.

Safety

Adverse events included one instance each of rash, herniated disc, dizziness, and a new diagnosis of prostate cancer in the control group. Within the treated group, adverse events included one urinary tract infection, 3 complaints of gas and bloating, one upper respiratory infection, one gouty arthritis exacerbation, and one complaint of hunger. The incidence of adverse events in the intervention group was not higher than the control group.

Laboratory findings

Initial CRP measurements were normal at intake screening laboratory evaluations in all participants. Subsequent readings after completion of the study did not differ significantly from initial measurements.

Discussion

WFPB diet was associated with a significant reduction in pain compared to an ordinary omnivorous diet, with statistically significant pain reduction seen as early as two weeks after initiation of dietary modification. Previous studies show that diets enriched with omega-3 fats and plant proteins tend to decrease subjective complaints of pain. These studies are limited by their design, size, and significant dropout rates. To our knowledge, including an exhaustive literature search, this is the first randomized controlled trial to examine the effects of a WFBP diet on subjective pain reports and functional status/ limitation due to fibromyalgia.

The primary mechanism by which diet reduces subjective pain may be a result of normalization of the fatty acid profile and reduction in exposure to inflammatory protein precursors. Western diets are high in arachidonic acid, which are modified into pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs work to reduce pain by limiting the metabolism of arachidonic acid. Arachidonic acid is found in animal foods and some vegetable oils. In addition, WFPB dieters have elevated serum levels of omega-3 fats compared to omnivores and even higher levels than fish eaters. The metabolism of alpha-linoleic acid, which is found in abundance in legumes, vegetables, and soy, produces antiinflammatory prostaglandins. The decrease in concentration of these prostaglandins may contribute to reduction in symptoms. Therefore, the adoption of a WFPB diet will dramatically reduce the availability of precursors necessary to produce painful prostaglandins. Other inflammatory markers have been identified in the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia. A 2015 systemic review [21] found these other markers to be interleukin 1, 6, and 8 (IL-1, IL-6, Il-8, respectively) as well as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). Studies evaluating the effect of non-pharmacological treatment on these specific inflammatory markers have not been conducted, but similar non-specific studies have shown modest effects of whole grain diets on inflammatory markers and T-cell immune responses [23].

Animal protein and fat consumption also increases the permeability of the small intestine to bacterial translocation, leading to systemic immune complex development. Overall changes to gut microbiota are noted in western diets, as well. These bulky immune complexes can lodge in small capillaries, resulting in inflammation and accumulation damage over time. It is hypothesized that this is responsible for the exacerbation and proliferation of many autoimmune and chronic inflammatory diseases, such as arthritis conditions [24].

The WFPB diet offers several advantages that may facilitate compliance [25]. Because dairy, eggs, and meat are completely omitted, there is no need to measure portions, limit the size of meals, handle raw meat, or be concerned of raw meat and egg safety precautions. A WFPB diet also appears to be easier to follow than previously studied raw diets and fasting, as evidenced by the high level of compliance and reasonable dropout rate of our study. Moreover, this diet elicited beneficial clinical results in as little as two weeks, which in turn will facilitate continued compliance. A common misconception is that the use of a plant- based diet without animal products would lead to malnutrition. Except for a very small risk of B12 deficiency in those who commit 100% to the diet, a WFPB diet based on unrefined plant foods supplies the adequate amounts of calories, protein, fats, vitamins, and minerals including calcium, zinc, and iron [26]. Interestingly, although the plant-based dietary profile (low- fat, high fiber) can lead to a diet that is less energy dense and reduce caloric intake, the WFPB diet is associated with increased nutrient density as well as increased concentrations of several vitamins and trace minerals. Therefore, the WFPB diet group may have ingested fewer calories than the treated group, even though they were encouraged to eat without calorie counting.

Weight loss and blood pressure reductions have been previously documented with WFPB diets [27,28]. The intervention group of this study also experienced a statistically significant decrease in weight loss and BMI. For every pound of weight lost, there is a four-pound reduction in mechanical load exerted on the knee during daily activities [29]. Weight loss of 15 pounds has been shown to reduce knee pain by 50% in overweight individuals with arthritis [19]. Weight loss likely contributed to the improvement of symptoms in the treatment group by decreasing the mechanical load on affected arthritic joints. However, most of the benefits of weight loss were associated with knee arthritis, and the diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia requires pain in multiple joint sites. Weight loss in the control group minimally decreased from baseline by 0.3 pounds compared to the approximately six pounds lost in the intervention group. This weight loss between control and intervention groups is consistent with what has been seen in previous studies.

Lastly, the results are applicable beyond this research setting because participants were studied in real time. They were not provided food and prepared their own meals or ate at restaurants. The study initiation techniques are easily duplicated in office settings as the intake interview training lecture and materials are available online.

Study Limitations

Because the symptoms of fibromyalgia follow a spectrum of severity, a participant's choice and motivation to complete the study likely was impacted by their symptom severity. Furthermore, nutrition research participants tend to be more knowledgeable about nutrition prior to initiating studies. However, regardless of the level of prior knowledge, all participants were given the same level of support after the intake interview.

Participant adherence to the instructed diet was based on a self-reported weekly 24-hour food recall. Actual adherence to dietary recommendations may vary due to recall bias. Extensive efforts were made to avoid expectation bias by giving the participants in the separate diet groups identical introductory and follow-up programs, with exception of the one-hour lecture, which may have led to a placebo effect. However, follow-up calls made to both the control and intervention group were equally frequent and both groups were encouraged to ask questions and/ or voice concerns. The observed responses to the intervention may have been falsely lowered by the control group’s knowledge of the dietary modification intervention, which resulted in some control group participants to implement aspects of the diet despite the request to continue their original diet. The study design is another limitation; a crossover design would have allowed both groups to receive treatment at different times and could possibly reduce variations in participants' diets.

The short study period may also be a limitation, but does not diminish the importance of the findings. Previous nutrition studies have shown support for short-term interventions, suggesting that nutrition interventions do not require a long duration to show benefit. For example, in patients with active chronic kidney disease, a vegetarian diet with reliance on grains as the primary protein source resulted in decreased serum phosphate concentrations in one week [30]. When a woman begins a low-fat diet, serum estrogen concentrations decrease by 15-50% in 2-3 weeks [31,32]. Dietary modification has been shown to result in increased functional capacity, decreased systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and decreased cholesterol in twelve weeks [27,28]. Of patients with mild, functionally limiting angina, 74% were pain- free after twelve weeks of dietary change [33,34].

Conclusion

Based on this data and other studies that have shown benefit of WFPB diets in chronic pain conditions, we hope to encourage an increased appreciation and clinical evaluation of dietary variables. Clinicians should understand the importance of discussing dietary modifications with patients suffering from chronic conditions such as fibromyalgia, in order to provide lasting benefit to this population. WFPB diet therapies can be recommended as a safe adjunct to the standard medical management of fibromyalgia.

Acknowledgment

This research was financially supported by a grant from Blue Cross Blue Shield foundation of Michigan. The study was designed and conducted under the supervision of Mary Clifton in cooperation with BCBS and the Institutional Review Board at Munson Medical Center. The paper was prepared with editorial assistance of Mary Clifton. The following investigators participated in the study: Chelsea Clinton, MD, Anna Clifton and Billy Zhang. Colleen M. Renier, BS prepared portions of the statistical analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

Mary Clifton has previously worked as a Speaker Bureau Consultant for Eli Lilly, Amgen, Medtronic Spine and Biologic and Forest pharmaceuticals. Mary Clifton has served as a consultant for Amgen Pharmaceuticals, Forest Laboratories, Eli Lilly, and Medtronic Spine and Biologic.

References

- Bellato E, Marini E, Castoldi F, Barbasetti N, Mattei L, et al. (2012) Fibromyalgia syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Pain Res Treat 2012: 426130.

- Ruiz-Cabello P, Soriano-Maldonado A, Delgado-Fernandez M, Alva- rez-Gallardo IC, Segura-Jimenez V, et al. (2016) Association of Dietary Habits with Psychosocial Outcomes in Women with Fibromyalgia: The al-Andalus Project. J Acad Nutr Diet 117(3): 422-432.

- Craig WJ, Mangels AR, American Dietetic Association (2009) Position of the American Dietetic Association: vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc 109(7): 1266-1282.

- Hänninen, Kaartinen K, Rauma AL, Nenonen M, Torronen RA, et al. (2000) Antioxidants in Vegan Diet and Rheumatic Disorders. Toxicology 155(1-3): 45-53.

- Adam O, Beringer C, Kless T, Lemmen C, Adam A, et al. (2003) Anti-inflammatory Effects of a Low Arachidonic Acid Diet and Fish Oil in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatol Int 23(1): 27-36.

- Nenonen MT, Helve TA, Rauma AL, Hanninen OO (1998) Uncooked, Lactobacilli-Rich, Vegan Food and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 37(3):274-281.

- Kjeldsen-Kragh J (1999) Rheumatoid Arthritis Treated with Vegetarian Diets. Am J Clin Nutri 70(Suppl 3): 594S-600S.

- Hafstrom I, Ringertz B, Spangberg A, von Zweigbergk L, Brannemark, et al. (2001) A Vegan Diet Free of Gluten Improves the Signs and Symptoms of Rheumatoid Arthritis: The Effects on Arthritis Correlate with a reduction in Antibodies to Food Antigens. Rheumatology (Oxford) 40(10): 1175-1179.

- McDougall J, Bruce B, Spiller G, Westerdahl J, McDougall M (2002) Effects of a Very Low-Fat, Vegan Diet in Subjects with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Altern Complement Med 8(1): 71-75.

- Kaartinen K, Lammi K, Hypen M, Nenonen M, Hanninen (2000) Vegan Diet Alleviates Fibromyalgia Symptoms. Scand J Rheumatology 29(5): 308-313.

- Donaldson MS, Speight N, Loomis S (2001) Fibromyalgia Syndrome Improved Using a Mostly Raw Vegetarian Diet: An Observational Study. BMC Complement Altern Med 1:7.

- Hafstrom I, Ringertz B, Spangberg A, von Zweigbergk L, Brannemark S (2001) A Vegan Diet Free of Gluten Improves the Sings and Symptoms of Rheumatoid Arthritis: The Effects on Arthritis Correlate with a Reduction in Antibodies to Food Antigens. Rheumatology (Oxford) 40(10): 1175-1179.

- Holst-Jensen SE, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, Monsrud M, Tarp U, Buus A (1998) Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis with a Peptide Diet. Scand J Rheumatol 27(5): 329-336.

- Kavanaghi R, Workman E, Nash P, Smith M, Hazleman BL (1995) The Effects of Elemental Diet and Subsequent Food Reintroduction on Rheumatoid Arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 34: 270-273.

- Hagfors L, Leanderson P, Sköldstam L, Andersson J, Johansson G (2003) Antioxidant Intake, Plasma Antioxidants and Oxidative Stress in a Randomized Controlled, Parallel, Mediterranean Dietary Intervention Study on Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nutr J 2: 5.

- Darlington LG, Ramsey NW, Mansfield JR (1986) Placebo-Controlled, Blind Study of Dietary Manipulation Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Lancet 1(8475) :236-238.

- Van de Laar MA, Van der Korst JK (1992) A Double Blind, Controlled Trial of the Clinical Effects of Elimination of Milk Allergens and Azo Dyes. Ann Rheum Dis 51(3): 298-302.

- Haugen MA, Kjeldsen-Kragh J, F 0 rre O (1994) A Pilot Study of the Effect of an Elemental Diet in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 12(3): 275-279.

- SJ Bartlett, S Haaz, P Wrobleski (2004) Small weight losses can yield significant improvements in knee OA symptoms. Arthritis and Rheumatism 50(9): S658.

- Beezhold BL1, Johnston CS, Daigle DR (2010) Vegetarian diets are associated with healthy mood states: a cross-sectional study in seventh day Adventist adults. Nutr J 9:26.

- Barnard RJ, Gonzalez JH, Liva ME, Ngo TH (2006) Effects of a low-fat, high fiber diet and exercise program on breast cancer risk factors in vivo and tumor cell growth and apoptosis in vitro. Nutr Cancer 55(1): 28-34.

- Rossi A, Di Lollo AC, Guzzo MP, Giacomelli C, Atzeni F, et al. (2015) Fibromyalgia and nutrition: what news?. Clin Exp Rheumatol 33(1 Suppl 88): S117-125.

- Vanegas, Meydani M, Barnett JB, Goldin B, Kane A, et al. (2017) Substituting whole grains for refined grains in a 6-wk randomized trial has a modest effect on gut microbiota and immune and inflammatory markers of healthy adults. Am J Clin Nutr 105(3): 635-650.

- Moreira AP, Texeira TF, Ferreira AB, Peluzio Mdo C, Alfenas Rde C (2012) Influence of a high-fat diet on gut microbiota, intestinal permeability and metabolic endotoxaemia. Br J Nutr 108(5): 801-809.

- Barnard ND, Scialli AR, Bertron P, Hurlock D, Edmonds K, et al. (2000) "Effectiveness of a low-fat vegetarian diet in altering serum lipids in healthy premenopausal women. American Am J Cardiol 85(8): 969972.

- Craig WJ, Mangels AR, American Dietetic Association (2010) Position of the American dietetic association: vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc 109(7): 1266-1282.

- Silberman A, Banthia R, Estay IS, Kemp C, Studley J, et al. (2010) The effectiveness and efficacy of an intensive cardiac rehabilitation program in 24 sites. Am J Health Promot 24(4): 260-266.

- Ornish D, Magbanua MJ, Weidner G, Weinberg V, Kemp C, et al. (2008) Changes in prostate gene expression in men undergoing an intensive nutrition and lifestyle intervention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105(24): 8369-8374.

- Messier SP, Gutekunst DJ, Davis C, DeVita P (2005) Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 52(7): 2026-2032.

- Beezhold BL, Johnston CS (2012) Restriction of meat, fish, and poultry in omnivores improves mood: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Nutr J 11: 9.

- Moe SM, Zidehsarai MP, Chambers MA, Jackman LA, Radcliffe JS, et al. (2011) Vegetarian compared with meat dietary protein source and phosphorus homeostasis in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6(2): 257-264.

- R Prentice, D Thompson, C Clifford, S Gorbach, B Goldin, et al. (1990) Dietary fat reduction and plasma estradiol concentration in healthy postmenopausal women. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 82(2): 129-134.

- Heber D, Ashley JM, Leaf DA, Barnard RJ (1991) Reduction of serum estradiol in postmenopausal women given free access to low-fat high-carbohydrate diet. Nutrition 7(2): 137-139.

- Frattaroli J, Weidner G, Merritt-Worden TA, Frenda S, Ornish D (2008) Angina pectoris and atherosclerotic risk factors in the multisite cardiac lifestyle intervention program. Am J Cardiol 101(7): 911-918.