Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess the practices and challenges of elementary school students’ with disabilities in physical Education. The major findings were large number of students with orthopedic, visual, and hearing impairments lacks access to practical exercises in the school. Though physical education was much favored by students with orthopedic, visual, and hearing impairments, it was noted that, these students were excluded from the practical activities, curriculum materials were found to be irrelevant. Lack of information on the status of students with disabilities is also found to be a challenging factor for effective inclusive education.

Keywords: Challenge; Disable; Elementary school; Participation; Physical education

Introduction

The right to live with self-respect as a human being leads to a continuous analysis of policies and services aimed at marginalized sections. In line with this, the convention on the right of the child demands that “all children have access to and an education of good quality”. Different initiatives by governments, NGOs, UN agencies, and others have addressed the special education needs of children with disabilities (Sakız, H., & Woods, C. (2015) [1]. It is possible to imagine that the combination of poverty, unawareness, war, drought with inadequate preventive and rehabilitation services could generate high prevalence of disabilities in Ethiopia. The nation in the developing countries lacks information and knowledge about persons with disabilities of the total population. There is scarcity of precise information about the magnitude and types of disabilities as well as their causes and outcomes (Ministry of Education, 2014) [2]. The problems of children with disabilities are diversified and complex; they are facing a variety of life challenges because of the complex socio-economic factors, which have an implication on the proper functioning and adjustment of children with disabilities. If the social setting is a rejection, insensitive, hostile, and destructive, these would not only make the adjustment of these people difficult but also affects their development and confidence. This is usually characterized by lack of trust, confidence in one-self, and the surrounding and feeling of hopelessness (Metts, R. L. 2000) [3]. Among many different factors, the central one is the educational participation of students with disabilities into regular educational settings. International education reform, in recent times, has paid attention on education for all and inclusive education. Hence, inclusive education for students with disabilities seems to be an international trend regardless of the existence of controversies over it. As indicated by various educators, one of the reasons for inclusion of students with disabilities into the regular classroom was to facilitate positive relationships, among both with disabled and with non-disabled students, (Horne, 1985) [4]. As to Mittler (2012) [5], in its broadest sense, inclusive education refers to the process of reforming and restructuring of a school with the aim of ensuring that every one of students can have access to the whole range of educational and social opportunities offered by the school. It is a process of including students with diverse needs into regular schools and classrooms instead of placing them in special institutions. Particularly, inclusion is the instructional and social integration of children with disabilities in a regular classroom,(Grotsky JN 1976) Schiemer M (2017) [6,7] strengthened the above ideas that inclusion is a shift towards schools that are structured around students’ diversity and can accommodate many ways of organizing pupils for learning to attain excellence in diversity.

The main purpose of any educational system of a country is to cultivate the individual’s capacity for problem-solving and adaptability to the environment by developing the necessary knowledge, ability, skill, and outlook. It may be difficult to attain this general objective of education in the presence of discrimination of some beneficiary groups based on race, color, religion, sex, physical conditions, political, or other opinions from specific practices of the school. To this end, different streams of education are used as tools to reach this educational goal. And physical education is one of the parts of general education which is developing rapidly in a wide range because of the more attention given to it at the center of its different benefits for every person including students with disabilities. Physical education is part of general education that contributes to the mental, physical, psychological, social, and spiritual growth and development of the child mainly through selected movement experiences and physical activities, (Pangrazi RP & Beighle A 2019) [8]. As it is indicated by Kraut, J. A. (1989) [9], a sound physical education program for students with disabilities can develop physical fitness and motor skills crucial for activities of daily living and orientation and mobility, a more positive self-concept and sense of personal worth and sport skills. Moreover, scholars today believe that a typical child can best learn to live a normal life if he/she participates as fully as possible in school life as other children. In fact, students with permanent handicap need assistance in making better adjustment to their disabilities and in discovering ways to balance for them, Johnson (1969) [10]. Therefore, school is the responsible organization to provide all aspects of physical education to the diverse group of personalities equally irrespective of any physical, mental, cultural, and other characteristics with the help of appropriate instructional strategies that can deal with the diverse needs of these students.

Solomon N (2010) [11], states that school children with disabilities are some of the school diversities and are the composition and characteristics of the so-called regular classes of physical education. Those who are responsible must be aware of these types of learners to be able to make an adequate teachinglearning environment possible, where in the target children could be successfully participated especially in the practical session of the subject so that they can be self- supportive and self-reliant. The purpose of this paper is, therefore, to examine the level of participation of children with disabilities such as orthopedic, visual, and hearing impairments in physical education practical activities and identify the major educational problems that may hamper them from participating. Disability can be easily perceived or identified relatively; hence, physical education teachers can support and encourage these school children in physical education practical classes according to their observable disabilities to advance their involvement. If not, there may be academic and other problems to successfully accommodate children with disabilities in all aspects of elementary school physical education. Thus, it may be central issue to reach the problems with this regard to building participatory Physical Education practical classes in which all children could participate and be beneficial.

All children are unique, differing from others in their intellectual, physical, social, spiritual, and emotional development. Nearly every one of the children is taught in regular classes, without the need for services, and the classroom teacher feels skilled at meeting their instructional needs. As a result, children with orthopedic, visual, and hearing impairments are some of these deviated groups from the normal limit that require special consideration from the teacher and others during physical education practical activities and in other subjects in general. Bucher CA (1975) [12], states that physical education is an integral part of the general educational process which promotes and integrates the physical, social, and psychological aspects of an individual’s life through direct physical activity. Therefore, it is only through the least restrictive environment and direct participation that children with disabilities could better attain such benefits from physical education or any other components of the general education. To this end, the educational movements undertaken with the aim of including children with disabilities into the mainstream classroom are firmly established in different nations. Different research recommend that among the various modes of educational deliveries for persons with disabilities, inclusive education is found to be ethically acceptable, pedagogically sound, psychologically commendable, and cost effective compared with special school provisions, UNESCO (1994) [13]. Therefore, the approach helps educational structures, systems, and methodologies to meet the needs of all children in the school.

As it has seen from the general trend, although most educators think inclusive education to be sound for learners with disabilities as well as for those with orthopedic, visual, and hearing impairments, a number of determinant factors interfered with its effective completion. This is also true for the successful accommodation of these students in physical education practical activities. For example, a study done by Solomon, N. (2010) magnified the following problems to participate students with disabilities in physical education practical classes. Teachers often perceived only the difference or impairment of the students rather than students’ ability, they show reluctance to include student with disabilities, they also found it difficult to assess these students in the practical activities of physical education, scarcity of materials especially designed to meet the needs of students with disabilities and lack of relevant training of physical education teachers. Thus, these and other factors could affect considerable involvement of students with disabilities in physical education practical activities.

Physical education and students with disabilities

Among the many definitions given by scholars, Freeman (1992) [14] defines physical education as “it is the sum of man’s physical activities selected as to kind and conducted as to outcomes”. Freeman’s definition sets on concern of the basic question whether educating only the physical aspect of the body is adequate to define the field. In view of the primary concept which puts body and mind to be two sides of a coin, physical education for the physical well-being of the human organism as the unification of mind and body, where a healthy physical status is closely linked to bright mind setting. As a result, physical education aims at developing the human person with a combination of a healthy mind and body as an indivisible whole during physical activities. With this notion, physical education has concern for and with emotional responses, personal relationships, group behaviors, mental learning, and other intellectual, social, emotional, and artistic outcomes. Physical education, gymnastics for example, was first used as a means of therapy for persons with disabilities. After that sport for people with disabilities has blossomed to include more international games, including three Olympic level competitive games targeting athletes with disabilities such as the Deaf Olympics (for those with hearing impairments), the Paralympics (for those with all other forms of physical disabilities such as limb loss and blindness), and the special Olympics (for those with intellectual disabilities). The expansion of physical education for persons with disabilities is reflected in the scholastic periodicals and journals that focus on adaptive physical education and recreation. And countless newsletters published by disability sports organizations worldwide.

Schiemer M (2017) [7]. strengthened the above idea that physical education works to develop the inclusion and well-being of people with disabilities in two ways. First, by changing what communities feel about persons with disabilities and second, by changing what people with disabilities think and feel about them. The first is basic to reduce the stigma and discrimination associated with disability. The second empowers a person with disabilities so that he/she may be aware of his/her own potential and advocates for changes in society to allow them to fully realize it. The community and individual impact of sport assists in reducing the isolation of people with disabilities and integrates them more fully into community life. Sport changes community perceptions about people with disabilities by consideration of their abilities and moving their disability into the background. Through sport, people without disability encounter them in a positive context and see them accomplish things they had formerly thought impossible. The assumptions about what people with disabilities can and cannot do are strongly challenged and reshaped by this experience. Sports change the person with a disability in an evenly profound way. It marks their first experience of human organization; that is, it helps them to make choices and take risks on their own. The gradual attainment of skills and accomplishments builds self-confidence needed to take on other life challenges such as pursuing education or employment. Sports also provide opportunities for people with disabilities to develop social skills, build friendships outside their families, exercise responsibly, and take on leadership roles. Through sports, people with disabilities learn greater social interaction skills, develop autonomy, and become empowered to lead and make change happen.

Conception and growth of adapted physical education/physical education for students with disabilities

Adapted physical education has grown from the premature corrective classes that were established specifically for people with disabilities. Because of the 1st and the 2nd world war, there were medical and surgical advances that improved the survival rate of many individuals. Many of those who survived were left with physical disabilities. Currently physical activity, including sports, has become a key technique to help in physical and psychological rehabilitation. About the same time, corrective physical education classes were started in different schools to improve postural deviations. The popularity of corrective physical education classes diminished during the late 1940s, and these began to be replaced by adapted physical education classes, where the heart was on games and sports to meet the needs of students with disability.

On the other hand, adapted physical activity does not categorize people with/without disabilities, as do eligibility procedures for special education placement. Instead, it analyzes individual differences related with problems in the psychomotor domain (Sherrill, 2009) [15]. Adapted physical education varies from regular physical education in its multi-disciplinary approach to individual program planning. It covers an age range from early childhood to adulthood. And it has educational accountability through the individualized educational planning and emphasizes supportive service among the school community, and the home to improve handicapped person’s capabilities (Reynolds & Mann, 2004) [16]. The objectives of adapted physical education programs differ from program to program depending on population characteristics, institutional expertise, and facilities. As Sherrill (1993) [17] stated, among the commonly accepted objectives of most programs are to grant students with opportunities to learn about and participate in a number of appropriate recreational and leisure time activities. An additional important characteristic of adapted physical education is it’s emphasized which is placed on engaging in physical activity rather than involving in a sedentary alternative to physical activity. The curricula of adapted for physical education are like that of regular physical education, but the procedures and methods for delivery of instruction are changed to meet the needs of students with disabilities.

Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to assess the

pedagogical practices and challenges in inclusion of elementary

school children with disabilities in practical classes found at

the study area. To this end, the study attempted to answer the

following research questions.

1. Do children with disabilities participate in the practical

classes of physical education?

2. What are the major factors that hinder the participation of

children with disabilities in physical education practical activities?

3. Are there strategies that are used to significantly

accommodate children with disabilities in physical education

practical classes?

Objective of the Study

The general objective of this study is to investigate the

existing participation of children with orthopedic, visual, and

hearing impairments in physical education practical classes and

to identify opportunities provided and determinant factors in

elementary schools. Therefore, the study consists of the following

specific objectives

• To see the extent to which children with disabilities are

participating in physical education practical classes.

• To identify the major factors that hinder the participation

of children with disabilities in physical education practical classes,

and

• To find out different strategies applied by physical

education teachers, school principals and district education

experts to create effective inclusive physical education practical

classes in the schools.

Materials and methods

Research Design

The purpose of this study was to assess the existing practices and challenges of elementary school children with disabilities in physical education practical classes. To meet this purpose, descriptive research methods were employed. The research was conducted through in- depth analysis of the condition of students with orthopedic, visual, and hearing impairments in upper elementary schools (grade 7&8). The target populations of the study were students who experienced orthopedic, visual and hearing impairments and attending their education in these regular schools in 2018/2019 academic year. Physical education teachers, school principals, and district educational experts were also included in the study. The primary consideration in sample selection for the study was to include an adequate number of respondents to perform meaningful data analysis. An attempt was made to include as many respondents as possible with an assumption that subjects would provide better information for the study. All students with orthopedic, visual, and hearing impairments from grades 7th and 8th elementary schools were identified. Because they were very few, comprehensive sampling techniques were employed in selecting physical education teachers, schools’ principals from the selected schools and district educational expert. Thus, 68 students with disability, 12 physical education teachers, 6 school principals, and 1 district educational expert were selected. Therefore, a total of 87 subjects were taken as respondents for the study.

Data Collection Instruments

To obtain pertinent information for the study, the researcher basically believes that it is important to use various data gathering tools which are relevant to generating data to the questions raised. Accordingly, questionnaire and interview were employed in this study. The questionnaire comprised issues related to the basic research questions. Therefore, a total of 17 questionnaires, both close ended and open ended i.e. for students with disability which contain 17 close-ended and open-ended, for orthopedic and hearing impairment as well as 12 physical education teachers filled in the questionnaire prepared for each. Students in this study were speakers of Amharic language so that the questionnaire was originally designed in English and latter translated into Amharic for them. The translation and editing were made by an English language expert who also knows Amharic. The questionnaire was then piloted for a group of ten disabled students.

Interview

Semi-structured interview guides were prepared for school principals and district education experts. Similarly, unstructured interviews were prepared and administered for students with visual impairments. The purpose of these interviews was triangulating the data that were found through questionnaires.

Data Gathering Procedures

The main data gathering tools for this study were questionnaires, and interview which were developed by the researcher based on related literature and research questions. The researcher distributed a total of 17 questionnaires for students with orthopedic, hearing impairment and for physical education teachers, and all were filled in and collected properly. Six students did not return the questionnaire. Similarly, an interview was conducted with 15 students with visual impairment, 6 school principals and 1 district educational expert with the help of unstructured and semi-structured interview guides prepared respectively.

Data Analysis

Both quantitative and qualitative research approaches were employed. Therefore, the data obtained through the set of questionnaires were analyzed quantitatively such as frequency distribution, percentage, and mean. Reliability of the questionnaire was calculated and found to be strong and consistent for the two categories: One for the practices/challenges and the other for students’ opinions. Thus, the Cronbach alpha reliability test was computed to both sections. Accordingly, the reliability test for the first category, i.e. practices was found to be 0.87, and for the opinions section was 0.91, in both cases, it was seen that the questionnaire was generally reliable so that it was employed for the main study.

Results and quantitative discussion of the study

Practice in physical education practical classes as perceived by students with disabilities

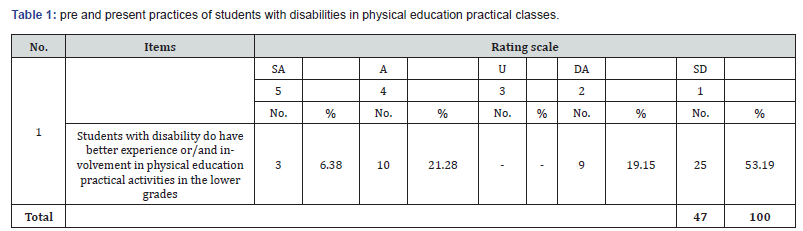

As was seen in the above item of Table 1, 25 (53.19%) of students with disabilities showed their strong disagreement concerning their previous experience in physical education practical exercise in their first cycle school, and only 10 (21.28%) of them had better participation previously. This indicates that the practices of these students in practical activity are negligible. Due to this, these students come to the next level of education with poor experience and awareness about physical education and in turn, it has an impact on their further education. In addition to this, when students with visual impairment respond for interviews, they replied that during physical education practical classes they never go to the sports field, and they stayed in their class and did their own work or sit idly somewhere in the school. And sometimes they go to sport field and watch materials of participant students under shadow until the class ends. In line with this idea, Bishop (1994) [18] states that, the pre-school and primary school is the time when many children attempt and develop fundamental motor patterns. However, in cases of the study group, this crucial period of introducing physical education to children with disabilities seems to be forgotten in the sample schools.

Practices and challenges of inclusive physical education practical classes as perceived by students with disabilities

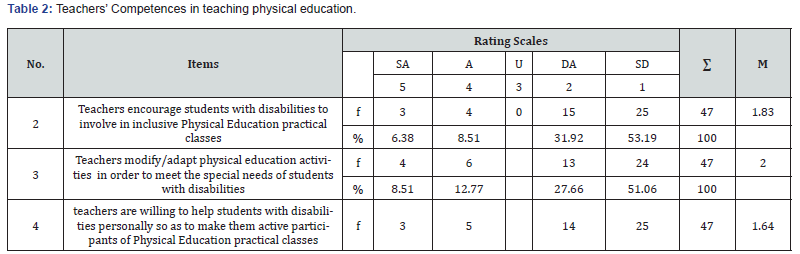

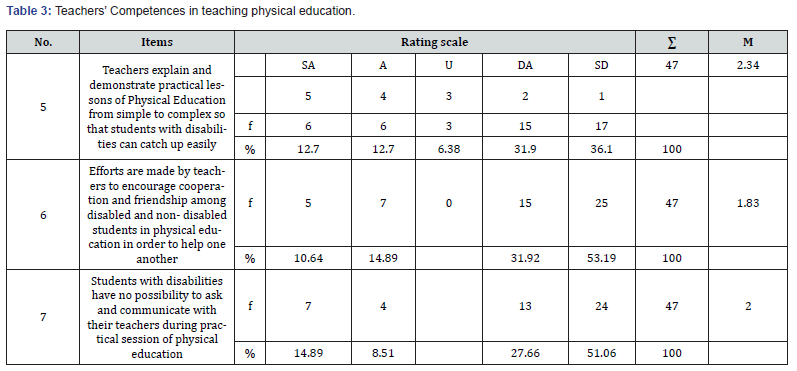

As one can understand from item 2 of Table 2, teachers’ competence in inclusive physical education is very low. For example, 25 (53.19%) of students with disabilities responded that teachers do not support and encourage these students to participate in practical physical education activities. However, giving special support and/or encouragement helps students with disabilities as well as those without disabilities to feel that they are an important part of the whole group. Moreover, interviewed students with visual impairment reflected that there is too little help and encouragement to make them participant. According to these respondents, physical education practical time is the time when they feel great depression. Because physical education practical time is the time when their peers are playing and enjoy while they are sit carelessly due to their impairment. Item 3 of the same table, the large number of these students, i.e. 24 (51.06%) reported that teachers did not try to modify/ adapt physical education activities so as to facilitate conducive inclusive environment. While Salend (1994) [19] states that there are various techniques for adapting the learning environment to promote maximum performance of mainstreamed students; the selection of an appropriate adaptation will depend on many factors, including the students’ readiness to learn and the teachers’ instructional approach. Regarding items 4 and 5 of Table 2, which are about the willingness and methodology of teachers, most students, i.e. 25 (53.19%) and 17 (36.17%) respectively expressed their strong disagreement and disagreement. This indicates that teachers had never shown interest in teaching students with disabilities and were not try to implement inclusive education effectively. Moreover, the teaching methods which are chosen by teachers were not convenient.

As indicated above in explaining lessons from simple to complex techniques in obtaining participation of the learners in teaching-learning process, the majority 32 (68.8) of students in the sample schools perceived the teachers’ ability to apply this style as discouraging. In regard to efforts made by teachers to encourage cooperation and friendship between disabled and non- disabled students in physical education practical classes, majority of 40 (85.11%) of the subjects replied they strongly disagree, and for item 7, 37 (78.72%) of respondents indicated that there is ineffective communication between teachers and students with disabilities in physical education practical classes. Classroom observation conducted at sample schools during physical education practical session also informed the same result. Similar findings and literature showed that teacher as the main barriers for inclusive education. Salend (1994) [9] advocates the need of communication in inclusive education as “successful main-streaming depends on an ongoing process of good communication and cooperation.” Therefore, from this table, one can judge that teachers’ competence to help students with disabilities is low in the sample schools because in all of the cases it is below average. Therefore, changing the attitudes of teachers, who are major parts of the process, is crucial to improve the participation rate of students with disabilities in practical classes of physical education.

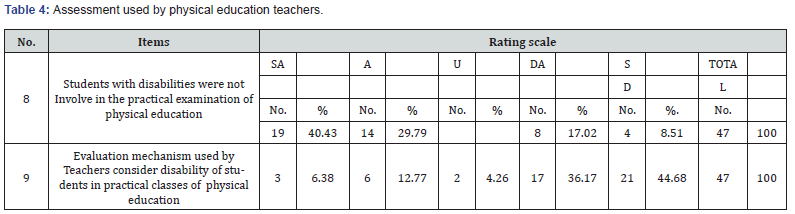

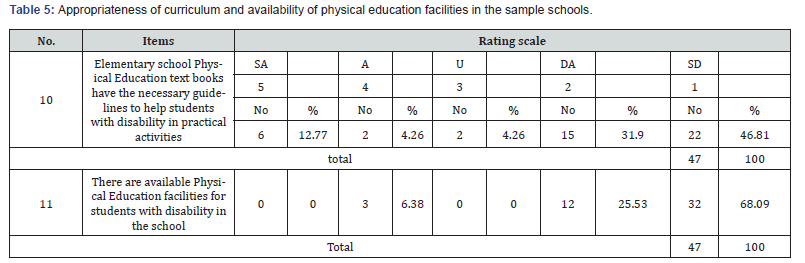

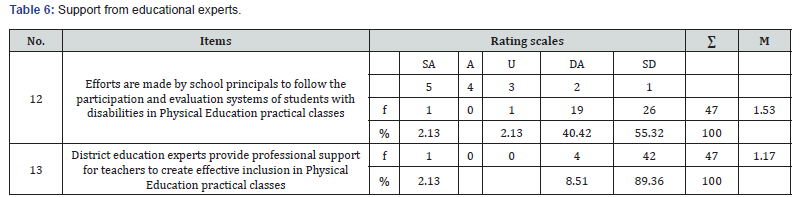

In item 8 of the above table, 19 (40.43%) and 14 (29.79%) of these students reported strongly agree and agree respectively concerning their rejection from the practical tests of physical education. As shown in item 9 of the above table, 21 (44.68%) of the respondents reported that an assessment system used by physical education teachers did not consider the special needs of students with disabilities. With regard to the above i.e. table 4, (Sherrill, 1993) [17], state that, assessment is an inseparable part of the students’ ongoing educational process, and particularly, it is critical for students with disabilities. Hence, they underlined that the teacher in the inclusive classes should know the purposes of assessment and types of assessment match the objectives. The issue of assessment and evaluation was raised for students with visual impairments. And they confirmed that they participated merely in the classroom theoretical tests. Therefore, their physical education result is very low since they are not participated in continuous practical assessment equal to other students. In Item 10 and 11 of Table 5, the respondent 22 (46.81%) and 32 (68.09) respectively reported strongly disagree about the appropriateness of elementary schools’ physical education textbooks and the availability of required facilities. However, it is easy to say that, adequacy of curriculum materials and availability of required facilities promotes the students’ achievement and at the same time contributes to effective inclusive education. Strengthening this view, Ministry of education (1994) [20] confirmed that “inadequate facilities, inadequate training of teachers, large class size, shortage of books, and other teaching materials all indicate the low quality of education provided.” The school administrators must be progressive sort of people. According to Van Gyn GH, Higgins JW, Gaul CA, Gibbons S (2000) [21], the principals must be an all-rounded person in looking for the problems and divers needs of children. This indicates that, if an integration school program for children with disabilities is to be successful, the principals should have a positive attitude towards inclusive education. But the data for item 12 above indicates that 26 (55.32%) of the students strongly disagreed with the efforts done by principals for the effective participation of students with disabilities in physical education practical activities in the sample schools. The mean value (1.53) of this item which is far from the average (3) also tells us that the negligible attention given for the unique need of students with disabilities in inclusive settings by the school principals. As indicated in item 13 of the same table, almost all 42 (89.36%) of the students showed their strong disagreement about the professional support given for teachers, principals, and students with disabilities in order to create conducive learning environment for inclusion in physical education classes. The mean value of this item (1.17) is also below the average, thus the school society particularly, teachers and principals didn’t have sufficient professional support from the experts who might be better skills and knowledge than them. Kassaw A, Abir T, Egigu A, Mesfin A (2017) [22], further states that absence of professional supports given in different form may affect teachers’ competence in teaching assessing students with disabilities, which could be crucial for quality education.

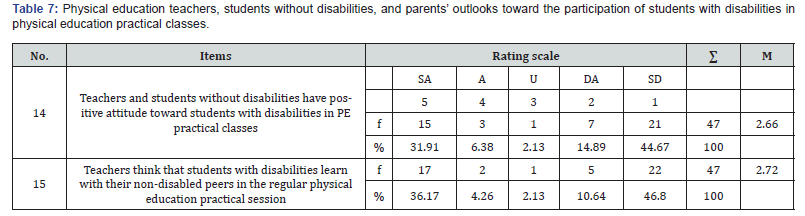

Positive perceptions of those who have close relations toward students with disabilities and their learning conditions play significant role in the multi-dimensional development of those who seek continuous assistance. Teachers, students without disabilities and parents are therefore, should have close contact to these students than any other body. With regard to this, item 14 of Table 7, 21 (44.67%) and 7 (14.89%) totally 28(59.57%) of respondents reflected their disagreement with the content that magnified the positive perceptions of teachers and students without disabilities to students with disabilities in physical education practical classes. Moreover, 15 (31.91%) and 3 (6.38%), in total 18 (38.30%) of these students agreed with the absence of the problem. In a similar way, for item 15 of the same table, 22 (46.80%) and 5 (10.64%) in total 27 (57.46%) disagreed with the idea provided. While 17 (36.17%) and 2 (4.26%), totally 19 (40.43%) of them agreed on the positive thinking that teachers might reflect to the participation of these students in the regular physical education practical classes.

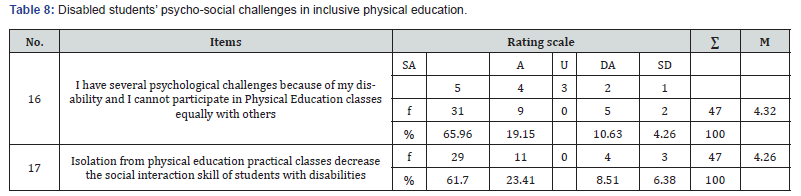

As the information obtained in table 8 above, the respondents notice that their exclusion from physical education practical classes affect their psycho-social aspects of life. For example, for item 16 which states the psychological problems faced by the students with disabilities due to their incapability to be participated in physical education class, therefore, majority of respondents 31(65.96%) and 9 (19.15%) which means the total of 40 (85.11%) respondents showed their agreement in different degree (strongly agree and agree respectively). In a similar way, for item 17 of the same table which is about the poor social interaction skill of students with disabilities because of their isolation from physical education practical classes, totally 40 (85.11%) of students reflected their agreement. When we observe the mean values of these items, i.e. 4.32 and 4.26, it is possible to conclude that the problems are very strong. Finally, interviewed students with visual, and orthopedic and hearing impairments in the open ended questionnaire were asked to identify major challenges that hamper their participation in physical education practical classes and potential strategies to overcome the problems.

Results and qualitative discussion of the study

Interview report obtained from school principals and district education expert

This semi-structured interview discussion conducted in faceto-

face manner with school principals and district education

expert in different time and place in order to find additional

information about the existing practice and challenges of

students with disabilities on physical education practical classes.

As a result, the responses from the school principals and district

education expert are summarized and presented as follows:

• Every one of the interviewees approved the presence

of students with disabilities such as orthopedic, visual, and

hearing impairments in the six sample elementary schools in

different distribution. Concerning their understanding about the

present state of inclusion in physical education practical classes,

nearly every one of the school principals believed that they know

physical education is given as a subject properly in the schools;

on the other hand, they do not have related information about

the participation of students with orthopedic, visual, and hearing

impairment in physical education practical classes. The rest

principals informed that students with orthopedic, visual, and

hearing impairments are accommodated in the school and attend

all subjects of general education together with students without

disabilities in the system which is inclusive education.

• They generalize their reply as their awareness regarding

the implementation of specific subjects like physical education is

low:

• For similar interview question, the district educational

expert replied to the same thing with that of the principals.

However, the district education expert underlines that, helping

students with disabilities in any inclusive setting is more of the

duty of the teacher since he/she has closer relation to the students

with disabilities than any other body. He further replied that, it

does not mean that excluding school principals from the system of

inclusive education, because they are responsible to promote the

ongoing process.

• Principals and educational expert respondents

also asked their credence about whether physical education

contributes for students with disabilities or not. Every one of

the respondents approved that, with no reservation, all subjects

do have equivalent contribution for all students either they are

disabled or non-disabled.

• About the support given from principals to teachers as

well as from educational experts to principals to build inclusive

physical education classes effective, most principals

• responded that support is given from the school to

the departments, however, their support is not adequate and

exclusively addressed inclusive physical education practical

classes.

• District education experts has also the same thought

regarding this question. He confirmed that his professional

support and encouragement is not particularly paying attention

on physical education, but also inclusive practical classes.

• For that reason, all the respondents agreed on the

common point that there is no special support and encouragement

from any of the two to advance the participation of students with

disabilities in physical education practical activities.

• Out look toward the participation of students with

disabilities in physical education or not, most principals replied

that, teachers have positive outlook to their students and their

subject.

• Concerning the sufficiency of the teachers’ training,

both groups replied that, regular schoolteachers are educated

effectively and qualified to each specific subject under different

programs, such as short term and long-term programs are

facilitated to upgrade their level of competency.

• About the evaluation mechanisms used by teachers in

practical activities of physical education, a few of the principals

informed that, they do not observe assessment of physical

education separately from other subjects. Conversely, some

of them reflected the idea that students with disabilities are

evaluated only in the theoretical class tests not in the practical

tests because of their disability. This implied that lack of universal

understanding among the sample school principals about

inclusive physical education resulted from low level of awareness.

• When asked about the accessibility and adequacy of the

essential equipment for physical education to make possible, all

the respondents indicated that physical education equipment

are not accessible in all most all the sample schools, this is due to

scarcity of budget.

• When asked about the subjects whether exclusion of

students with disabilities from the practical activities of physical

education influence them or not, all the subjects said that, inclusive

education has the concept that is providing equal opportunities to

all of the students without discrimination,

Conclusion and implications

Majority of the educators think about inclusive education to be ethically, morally, and pedagogically sound for students with disabilities; a number of barriers have interfered with its extensive completion. Consequently, considerable numbers of students with disabilities were inaccessible to participate in physical education practical activities in the school. Therefore, based on the findings of the study it can be concluded that low level of awareness of teachers about the right of students with disabilities, poor knowledge and skills of physical education teachers, scarcity of facilities and equipment, absence of support and encouragement from principals and educational experts, and psych-social challenges hindered students with disabilities to be participant in physical education practical classes. As a result, to create inclusive physical education in the sample schools of the study area, changing the prevailing conditions is indispensable. Various factors influence and regulate the development of inclusion, some of the determinant factors are the attitudes of the community towards children with impairments and inclusion, narrow understanding of the concept of impairment and a hardened resistance to change. Teachers’ perceptions are seen as the key factors for effective inclusion. Inclusion has been based on the assumption that teachers are willing to acknowledge students with disabilities in regular class and be responsible to meet their needs (Teferra 1999) [], Schiemer M(2017) [23,24] stated that it is common knowledge that there are a significant number of persons with disabilities in Ethiopia, though; the exact number of persons with disabilities is not known. Apart from what cultural and traditional attitudes societies may have disabilities and bodily impairments as naturally a part of human life at birth and death. Disabled children have existed at all times and in all cultures throughout the world (Seymour H, Reid G, & Bloom GA 2009) [21].

References

- Sakız H, Woods C (2015) Achieving inclusion of students with disabilities in Turkey: Current challenges and future prospects. International Journal of Inclusive Education 19(1): 21-35.

- Ministry of education (2014) Transitional Government of Ethiopia education and training policy. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Metts RL (2000) Disability issues, trends, and recommendations for the World Bank (full text and annexes). Washington, World Bank.

- Horne MD (1985) Attitudes toward handicapped students: Professional, peer, and parent reactions. Psychology Press.

- Mittler P (2012) Working towards inclusive education: Social contexts. Routledge.

- Grotsky JN (1976) The Concept of Mainstreaming: A Resource Guide for Regular Classroom Teachers.

- Schiemer,M (2017) Education for children with disabilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: developing a sense of belonging Springer Nature p: 200.

- Pangrazi RP, Beighle A (2019) Dynamic physical education for elementary school children. Human Kinetics Publishers p: 741.

- Kraut JA (1989) Foundations of Education for Blind and Visually Handicapped Children and Youth: Theory and Practice. Archives of Ophthalmology 107(8): 1126-1127.

- Johnson PR (1969) Physical education for blind children in public elementary schools. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 63(9): 264-271.

- Solomon N (2010) Educational challenges of the hearing-impaired children: The case of two selected special schools.

- Bucher CA (1975) Foundations of physical education. Mosby.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (1990) World declaration on education for all.

- Freeman WH (1992) Physical education and sport in a changing society (No. Ed. 4). MacMillian Publishing Company.

- Sherrill C (1998) Adapted physical activity, recreation and sport: Crossdisciplinary and lifespan. WCB/McGraw Hill, 2460 Kerper Blvd., Dubuque, IA 52001.

- Reynolds CR, Fletcher-Janzen E (Eds.) (2004) Concise encyclopedia of special education: a reference for the education of the handicapped and other exceptional children and adults. John Wiley & Sons.

- Sherrill C (1993) Adapted physical education, recreation and sport: Cross disciplinary and lifespan approach. Madison, Wisconsin: Brown & Benchmark.

- Bishop P (1994) Adapted Physical Education: A Comprehensive Resource Manual of Definition, Assessment, Programming and Future Predictions. Educational Systems Associates, Incorporated.

- Salend SJ (1994) Effective mainstreaming: Creating inclusive classrooms. Macmillan College.

- Ministry of education (1994) Transitional Government of Ethiopia education and training policy. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Seymour H, Reid G, Bloom GA (2009). Friendship in inclusive physical education. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 26(3): 201-219.

- Kassaw A, Abir T, Ejigu A, Mesfin A (2017) Challenges and opportunities in inclusion of students with physical disabilities in physical education practical classes in North Shewa zone, Ethiopia. American Journal of Sports Science 5(2): 7-13.

- Teferra T (1999) Inclusion of Children with Disabilities in Regular SC, hools: Challenges and Opportunities. The Ethiopian Journal of Education 19(1): 29-64.

- Van Gyn GH, Higgins JW, Gaul CA, Gibbons S (2000) Reversing the trend: Girls' participation in physical education. Physical & Health Education Journal 66(1): 26.