Abstract

Repetitive asymmetrical activity, heavy lifting, bending, and twisting movements occur when engaged in daily non-riding yards and stable duties and have been suggested to potentially cause pain. This research aimed to explore the impact of yard and stable duties on pain experienced by riders. An adapted short-form McGill pain questionnaire was used to measure the intensity and location of pain and time spent carrying out stable duties. Eighty-one percent of the 512 participants in an online questionnaire reported pain. Riders had an increased likelihood of having back and neck pain than no pain (17.9 OR, 95% CI 11.9-27.0). The majority (84%) of participants reported complete at least 1 hour of stable duties every day. As the daily hours spent in stable duties increased more participants reported experiencing pain, with carrying associated with the most severe pain. No significant differences were seen in pain levels between the recreational and the competitive amateur riders performing yard duties (Mann Whitney U Test, p values > 0.05; grooming p=0.816; carrying p=0.819; sweeping p=0.629; mucking out p=0.770). The high incidence of pain reported in competitive and recreational, amateur riders is concerning as pain negatively impacts wellbeing, enjoyment and quality of life. As such further research to develop interventions aimed at reducing chronic pain in this population is warranted.

Keywords: Equestrian; Injury; Asymmetry; Chronic pain; Repetitive strain

Introduction

Horses having traditionally been used for agriculture, transport, and military purposes, are now in developed countries owned primarily for leisure, companionship, and sport purposes. The estimated horse population in Great Britain is about 850,000 horses; 631,000 are privately owned; 95,000 are professionally owned (British Equestrian Trade Association, 2023) [1]. The majority of horse riders in the UK do not earn an income from riding and as such are classed as amateur riders. Riders that do not take part in competition are known as recreational riders, as opposed to competitive riders (Dumbell, 2022) [2]. Although horses are domesticated, they are inherent flight or flight animals who are often unpredictable in nature. Weighing approximately 500-800 kgs and capable of moving at 55 kmh-1, humans are at risk of being injured during the interaction with horses. Acute injuries such as fractures, confusions or concussions are recognised to frequently occur during riding and handling horses (Ball et al., 2007; Mayberry et al., 2007; Sorli, 2000) [3-5]. Research is increasingly recognising the prevalence of chronic injuries (lasting at least 12 weeks) in horse riders, with chronic injuries reported in 76-88% of riders (Lewis and Baldwin, 2018; Kraft, 2007) [6,7]. Whilst studies identify type and frequency of injury and pain, few studies explore the reasons why chronic pain in riders occurs so frequently (Lewis and Baldwin, 2018) [6]. Chronic pain in horse riders has been associated with discipline, equipment used, rider position and rider asymmetry (Lewis et al., 2023; Lewis and Kennerly, 2017) [8,9]. Thirty percent of event riders competing at FEI 2-4* attributed their pain to performing yard work and stable duties (Lewis et al., 2018) [10], yet the impact of these activities on recreational and competitive amateur riders is yet to be explored.

As riders and horse owners are responsible for the health and welfare of the horses they manage (Williams and Tabor, 2017) [11], one area worthy of exploration and often neglected when considering rider pain is stable management and yard work. The care and management of horses involves undertaking various yard work and stable duties on a daily basis. These activities associated with caring of horses, include but are not limited to mucking-out stables, sweeping, lifting and carrying hay and bedding, feeding and grooming the animal, and require physical effort for periods exceeding 15 minutes multiple times in a day (Löfqvist et al., 2007) [12]. These activities are also repetitive and often asymmetrical (Pugh and Bolin, 2004) [13] and have the potential to contribute to the high incidence of chronic pain recorded in riders. Despite their potential influential effect, the contribution of equine management tasks to pain in riders has not been evaluated to date. The aim of this descriptive study was to describe the impact of common stable and yard duties on self-reported pain in amateur riders, compare competitive and recreational riders’ experience of pain and identify strategies that riders use for reducing or managing pain associated with these activities.

Methods

Following institutional ethical approval (ETHICS2018-68) and informed consent, a six-part 34 question online survey (Surveymonkey™) was completed by riders aged over 18 years. The online questionnaire was accessible for a one-month period. The questionnaire was delivered online to access a geographically diverse population and allow them to respond at their convenience. Volunteer participants where recruited from personal contacts via email, and a number of specialist equestrian social media sites (such as the Horse & Hound forum) were a link to the questionnaire was posted. A snowball sampling technique was employed where those receiving an email regarding the questionnaire were asked to send the email to other horse riders that they knew. Due to the anonymity of the questionnaire, completion of the form was considered as consent to take part in the study (which was explained in the participant information sheet preceding the survey).

Participants

To be eligible to participate, riders had to meet defined inclusion criteria: be over 18 years old, not be paid to horse ride (i.e. be amateur horse riders (Dumbell, 2022)) [2] and either own or look after a horse daily, engaging in associated yard/stable duties.

Survey design

The survey was adapted from the pain survey used by Lewis et al. (2018) [6], using principles created by Diem (2002) [14]. The survey comprised 34 questions, including a mixture of closed – response (e.g. Yes / No and ordinal scale responses) and openresponse questions. It was designed to take no longer than 15 minutes to complete. Questions focused on rider demographics, riding profile, yard work, physical activity, inactivity, pain, pain management and effect of pain on lifestyle. To accurately evaluate rider pain questions relating to type, feeling and intensity of pain, questions were adapted from validated questions from the short form McGill pain questionnaire (Melzack, 2001) [15]. The final section was modified for equestrian athletes from the Oswestry pain questionnaire (Fairbank and Pyncent, 2000) [16] to assess the impact of pain on lifestyle. Previous research (Lewis et al., 2023; Lewis et al., 2018) [8,6] reported the validity of this approach for clarity of wording; use of standard English and spelling; reliance of items; absence of biased words and phrases; formatting of items and clarity of instructions.

Data analysis

Data from the Surveymonkey® package were downloaded into a Microsoft Excel (2010) [] spreadsheet. Only questionnaires completed in full were taken forward for analysis. Descriptive statistics reported the frequencies and percentages of respondent self-reported pain. Odds Ratios (OR) were utilized to assess prevalence of pain experienced by riders, and the 95% confidence interval limits (CI) were calculated following the method described by Bland and Altman (2000) [17]. Data met nonparametric assumptions therefore a series of Mann Whitney U analyses identified if differences occur between recreational and amateur competitive riders. Significance was set at p<0.05 throughout unless otherwise stated. Data were analysed using SPSS for Windows version 24.

Results

Respondent Demographics

Of the 512 complete questionnaires analysed 98% of respondents were female (n=501) and the remaining 2% (n=10) were male. Fifty-two percent (n=266) of respondents were recreational riders and 48% (n=246) amateur competitive riders.

Reported pain and location of pain of recreational and amateur competitive riders during yard duties

The majority, 89.1% (n=456) of the riders, reported pain while carrying out stable duties and 10.9% (n=56) reported that they did not experience pain whilst carrying out stable duties (OR: 8.1, 95% CI 6.2 to 10.7). The majority of the riders in pain (53.4%; n=244) reported the presence of chronic pain, with 46.8% (n=222) acute pain. Recreational and amateur competitive riders reported they were slightly more likely to experience chronic pain than acute pain (1.2 OR, 95% confidence interval (CI)1.0 to 1.4). Over 40% of those in chronic pain reported suffering pain for over 6 years (n=100 from 244) Of the riders reporting pain (n=456), the majority, (94%, n=430) reported experiencing back or neck pain than not experiencing pain in that area (17.9 OR, 95% CI 11.9 to 27.0). Three hundred and eighty seven participants (75.6%; n=456) reported pain in other areas (Table 1), including 22 (5.7%) who reported pain in only one other area, whilst the majority (94.3%; n=430) reported pain in multiple other areas.

Stable duties and respondents’ experience of pain

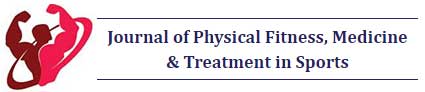

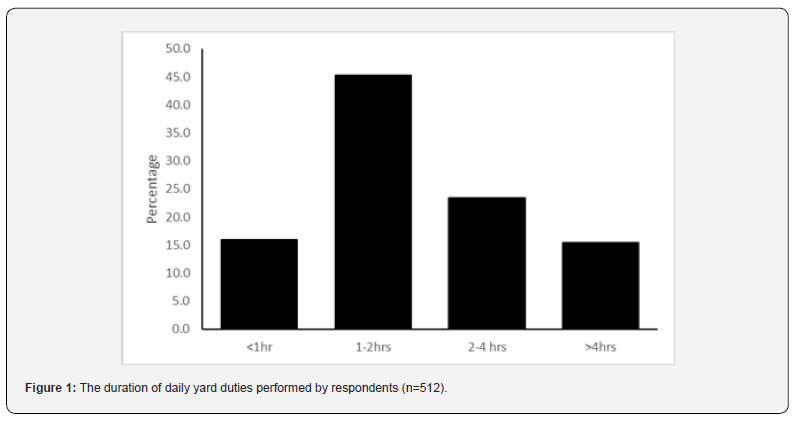

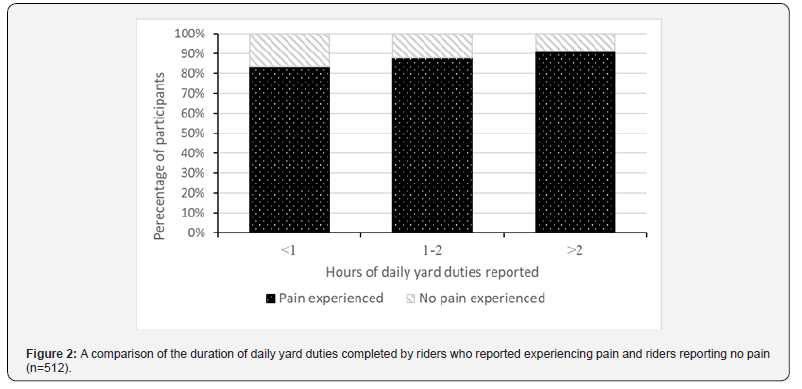

The majority (84%; n=430) of respondents reported completing at least 1 hour of stable duties every day (as shown in Figure 1). The most common duration of stable duties was between 1 and 2 hours daily (45.2%; n=231). The likelihood of respondents experiencing pain increased as the hours of daily yard duties completed increased (Figure 2). Riders who completed more than 2 hours of yard duties were more likely to experience pain than those who reported completing less than 1 hour of yard duties a day (OR: 1.6, 95% CI 0.9 to 2.9). When respondents experiencing pain were asked what severity of pain (on a five point scale from mild, through discomfortable, distressing (moderate pain) to horrible and excruciating (severe pain) was experienced during different yard duties it could be seen that grooming horses caused the least pain (mild pain), whereas sweeping, mucking out and carrying water buckets and haynets caused more pain (moderatepain) (Figure 3). Carrying water buckets or haynets caused the most severe pain with 32.6% of participants experiencing pain, experiencing distressing pain to excruciating pain during this activity. Fifty percent (50% of n=387) of respondents experiencing pain in areas other than the back and neck reported that daily yard duties made that pain worse. When the levels of pain were compared between competitive riders and recreational riders, no significant differences were found between the different yard duties (grooming p=0.82; carrying p=0.82; sweeping p=0.63; mucking out p=0.77).

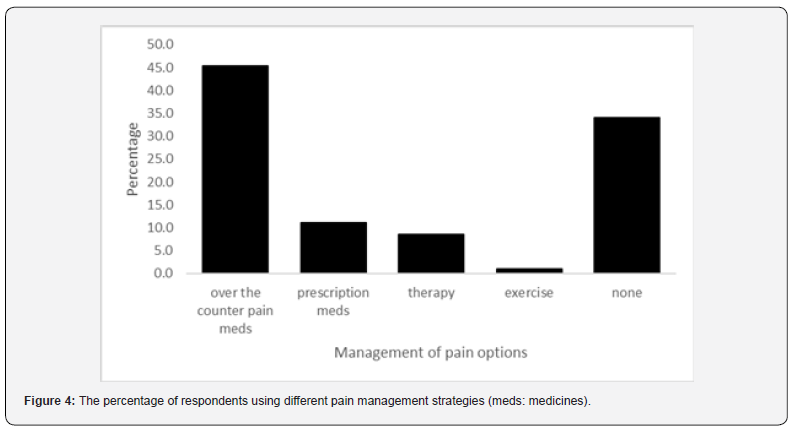

Pain management strategies

The majority of respondents who reported experiencing pain used strategies to manage their pain (66%; n=321) (Figure 4). Fifty-six percent (n=272) used medication as their preferred strategy and 9% (n=44) preferred therapy or exercise. Across the cohort, individuals were more likely to take medication than not take medication to manage their pain (OR: 1.2, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.5). Eighty percent (n=218) of respondents who took medication to manage their pain used over the counter drugs (NSAIDs), 20% (n=54) used prescription drugs. Respondents were more likely to use over the counter than prescription drugs (OR: 4.1, 95% CI 2.5 to 6.6).

Discussion

Location of pain

Pain was experienced during yard duty activities by 89% of the recreational and amateur competitive respondents in this study. The intensity of the pain experienced ranged from mild to severe, with some respondents reporting excruciating pain. These results correspond to the levels of pain previously reported whilst riding in elite dressage riders (74%) (Lewis and Kennerly, 2017) and event riders (96%) (Lewis and Baldwin, 2018). Davies et al. (2022) reported that 52% of horseracing staff took pain medication at least once per week to manage daily tasks at work, many of which would involve yard duty activities. It is therefore likely that more than 52% of horseracing staff were experiencing pain. Chronic pain was reported by 54% of respondents in this study. Chronic back pain is common, with 15% of the adult population estimated to be in pain at any one time (Krismer and Van Tulder, 2007) [18] and a common occurrence within people engaging in sporting activities including riding (Cook et al., 2006; Kettunen et al., 2002). This study found that 94% of recreational and amateur competition riders experienced back and neck pain, at a much higher than level than recorded in the general population and higher then reported in other equestrian populations: elite dressage riders 88% (Kraft et al., 2009) [7], 76% (Lewis and Kennerly, 2017) [9]; showjump riders 62% (Lewis et al., 2018) [10]; eventing riders 52% (Lewis and Baldwin, 2018) [6], and horseracing staff 23% (Davies et al., 2022) [19]. Back pain is a multifactorial disorder; with individuals’ occupation, psychosocial factors, posture, demographics and medical history all contributing to chronic pain and it is therefore difficult to define the exact causal factor for the level of chronic back and neck pain recorded in the recreational and amateur competitive riders surveyed. Manchikanti (2009) [20] found labourers, cleaners and nurses, all occupations with heavy physical strain, frequent lifting and postural stress were likely to experience back pain. An increase in days of absence from work due to back pain has been strongly associated with heavy physical work in studies (for example: Balagué et al., 2012; Anderson et al., 1993) [21,22]. Completing yard duties often includes heavy physical strain when lifting heavy objects such as: buckets of water, bedding, bales of hay and feed bags, therefore it is likely these activities contribute to the self-reported chronic pain here.

Recreational and amateur competitive riders in this study also reported pain in the shoulder (45%), knee (42%) and hip (40%). Pain during riding has been previously reported in FEI 2-4*event riders, where 48% experienced shoulder pain and 25% hip pain (Lewis and Baldwin, 2018) [6]. In contrast, only 5% of dressage riders (Lewis and Kennerly, 2017) [9] reported experiencing pain during riding in the shoulder complex, 8% in the hips, 8% in the ankle, and 3% in the legs. People engaged in equestrian activities (whether yard duties or riding) appear to report frequently experiencing pain, in a range of body regions The potential for injury from repetitive movements, such as lifting, and an onset of musculoskeletal disorders such as osteoarthritis (Burbank et al., 2008; Cutlip et al., 2009; Van Tulder et al., 2007; Arden and Nevitt, 2006; Barbe and Barr, 2006) [23,24,25,26] highlights the importance for riders to take adequate rest time to avoid repetitive movements; to receive training on lifting and yard work movements to reduce the likelihood of injury; and to avoid excessive loading. The association between bending, lifting, twisting and back pain prevalence has been established in prior studies (Majid and Tuumees, 2008; Hsiang et al., 1997) [27,28], and has been identified as a causal factor for dropout in sporting and leisure activities such as golf (Gosheger et al., 2003) [29]. It appears likely that pain will also impact riders’ participation in sport, their riding career longevity (Lewis and Kennerly, 2017) [9], and their enjoyment of owning and caring for their horse. Research suggests that owning a horse is ‘a way of life’ (Dashper et al., 2017) [30] and this may influence rider decision making (Williams and Tabor, 2017) [11]. Research in horseracing reports a culture of presenteeism (McConn-Palfreyman et al., 2019; Davies et al., 2024) [31] where stable staff will work regardless of being in pain or discomfort. This may be due to their feelings of obligation and commitment to caring for the horses and putting the horses’ wellbeing before their own.

Pain and stable and yard work

The majority of respondents completed yard work for 1-2 hours per day. Taking care of horses and completing yard duties daily can be hard work and requires riders to have a baseline of physical fitness (Douglas et al., 2012) [32]. Riders in general have shown scores in Functional Movement Screening™ (FMS) tests of 14 or below (Decker et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2019) [33,34]. The low scores and asymmetric movement patterns reported suggest riders are predisposed to increased risk of pain and injury as a result of flawed movement patterns (Cook et al., 2006) []. The repetitive asymmetrical movement patterns when carrying out stable duties (along with other daily tasks) could be a causal factor for pain (Löfqvist and Pinzke, 2011) [12]. Interestingly 50 % of riders who reported pain in areas other than the back or neck in this study felt having to complete daily yard duties made their pain worse, a phenomenon also reported by 35% of elite event riders (Lewis and Baldwin, 2018) [6]. Participants in this study that completed an hour or more of yard duties daily were three times more likely to report pain than participants completing less than an hour of yard duties daily.

Riders, including those in this study, commonly report that chronic pain negatively affects their quality of life and riding performance. Existing literature highlights how chronic pain hampers functional capabilities such as mobility and engagement in everyday activities (Burbridge et al., 2020; Linton et al., 2000) [35]. Burbridge and colleagues (2020) specifically identify the adverse effects of chronic pain on mobility (e.g., walking, sitting/ standing, bending, lifting), daily activities (e.g., housework, driving, employment), and broader life functions (e.g., mood, sleep, socializing, appetite). Further research is required to examine the impact of chronic pain on other life domains for riders, including sleep disturbances. Recent studies suggest that pain might contribute to sleep disruption, which in turn affects overall quality of life (Davies et al., 2024) []. Chronic pain can also impact on broader aspects of life including leading to decreased job market participation and household income (McNamee and Mendolia (2014) [36]. This financial strain could be particularly significant for the 331,000 horse-owning households in the UK, already concerned about the rising costs of horse care (NEWC, 2023) [37]. Davies et al. (2023) [] highlighted that chronic pain is negatively correlated with reduced job security in racing yard staff, emphasizing the influence pain can have on economic impact within the equestrian sector. Chronic pain is a major factor in sports retirement and dropout rates (Molenaar et al., 2021; Trompeter, Fett, and Platen, 2017; Crane and Temple, 2015; Maffulli et al., 2010) [38,39,40]. Longitudinal studies are necessary to determine whether chronic pain contributes to participation and dropout rates in equestrian activities. Pain’s multifaceted nature includes physical, cognitive, and behavioural components (Verhaak et al., 2007) [41]. Long-term chronic pain is linked to depression, diminished mental health, and lower life satisfaction (McNamee and Mendolia, 2014; Breivik et al., 2006) [36,42]. While this study did not focus on the emotional aspects of pain in riders, this is a critical area for future research, as noted by Linton (2000) [35], who associates chronic pain with emotional distress, mental fatigue, and anxiety.

Nixon (1993) [43] identified a “culture of risk” among athletes, where pain is often rationalized for the sake of sporting success. This culture, which normalizes pain and even glorifies competing despite it, may explain the high levels of chronic pain reported among riders. The equestrian community’s attitudes towards toughness and the necessity of enduring pain (e.g., “you are not a rider until you have fallen off 10 times” (Young, 2004)) [44], may further entrench these norms. Similar attitudes have been observed in other sports, such as rhythmic gymnastics, where pain is often perceived as a weakness (Cavallerio, Wadey, and Wagstaff, 2016) [45]. In horse racing, cultural acceptance of pain and injury is prevalent, with jockeys often continuing to ride despite pain due to industry expectations (Davies et al., 2021; McConn-Palfreyman et al., 2019) [46]. Yard staff also consider pain and injuries as an inherent part of working with horses (Davies et al., 2022) [19]. The extensive commitment and responsibility involved in horse care contribute to this tolerance of chronic pain (McConn-Palfreyman et al., 2019; Dashper, 2017) [46,30]. Similar attitudes towards pain and toughness are seen in agriculture and the military (Volkmer and Lucas Molitor, 2019; Hauret et al., 2010) [47,48], indicating a need for strategies to change these deeply ingrained cultural norms in the equestrian world. Jones McVey (2021) [49] highlighted that equestrians perceive injury as unavoidable, it should not delay or prevent equestrian activities, including daily care, yard work and ridden exercise. These findings, reveal that horse owners recognize the impact of pain on their mobility and daily activities, which are integral to horse care and riding (Lewis et al., 2023; Davies et al., 2022) []. Moral or ethical obligations to animal welfare are often cited as reasons for continuing daily care, with owners and carers often concerned that the level of care provided is reduced in their absence, a phenomenon observed in other animal care sectors (Figley and Roop, 2006) [50]. This suggests a wider cultural connotation between human attitudes towards pain and its influence on their behaviour which is linked to the responsibility of caring for horses.

While this study did not explore riders’ perceptions of the impact of chronic pain, further qualitative research is recommended to understand how riders view their pain and why they continue to ride despite chronic pain. The normalization of pain in sport may lead athletes to develop coping strategies to ignore pain, a phenomenon observed in riders and suggested by Thompson, Kibarska, and Jague (2011) [51]. Current sport psychology literature focuses predominantly on acute pain, underscoring the need to investigate chronic pain experiences in equestrians further. Few studies have evaluated the mechanical properties of performing yard work. Whilst there have been many technical developments in equipment and tack related to riding horses, the equipment and process of common yard duties such as mucking out, preparing the horse’s stable and sweeping have not evolved or improved. These tasks involve over 60 % of work postures where the individual’s back was bent, twisted, or both, and Löfqvist and Pinzke (2011)[12] concluded that to protect riders from repetitive strain injuries which could contribute to the development of chronic pain, it is important to find preventative measures to reduce workload or to determine favourable ergonomic designs and processes to limit the impact of necessary yard activities. It is therefore important to provide ways of reducing workloads and minimizing pain and injury, which this study suggests are prevalent concerns within the recreational and amateur competitive rider population. To investigate pain management strategies in riders was a key objective of this study as previous findings suggest that riders do not seek help when required (Lewis and Baldwin, 2018) [6]. Sixty six percent of respondents in this study had not had a medical diagnosis for their pain and many had been suffering with their pain for six years or longer. This highlights the importance of education on optimal treatments for pain and seeking medical support to diagnose and manage pain. Similar to results seen in competition riders, 88 % of respondents used only over the counter pain medication and relatively few sought help with pain management. The side-effects to the gastrointestinal tract, liver and kidneys of taking readily available over the counter non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), particularly over a period of time has been well documented (Wadman, 2006; Riordan et al., 2002) [52,53]. As such riders should seek more holistic approaches to managing their pain.

Ball et al. (2009) [54] suggests that whilst many riders continue to ride with pain, it may have performance limiting effects (Munz et al., 2014; Wipper et al., 2000) [55,56]. Douglas et al. (2012) [32] also suggested that often the rider does not consider themselves to be an athlete and that rest and rehabilitation seen in other sports, may not be present as much in equestrianism. Competitive athletes, including horse-riders, are often of an extrovert personality and are risk-takers (Watson and Pulford, 2004) [57]. Often riders know the risks involved around horses (Tompson et al., 2015; Wolframm et al., 2015) [58,59] and assume they are likely to get injured at some point due to the nature of the sport (Jones McVey, 2021) [49]. This may make riders resilient but may be a contributing factor resulting in acceptance of high levels of pain (Galli and Vealey, 2008) [60]. Riding with pain has been suggested to limit performance, uneven rider weight pressure on the horse’s back and asymmetric movement patterns is likely to be detrimental to equine welfare (Lewis et al., 2023; Lewis and Baldwin, 2018; Lewis et al., 2018; Lewis and Kennerley, 2017) [6,8,9,10]. The Ten Principles (International Society for Equitation Science, 2024) [61] for training horses states that one aid or cue must be applied at a time and that the time of the pressure release of the aid is important to prevent confusion in the horse and a stress response. The rider will find this difficult to do if they are not in optimum physical condition, therefore, for equality as well as performance, it is essential that riders address any pain, postural or movement asymmetry and general functional movement deficits.

Limitations

This study used a self-completed questionnaire and there is no way of identifying, understanding, and describing the population that could have accessed and responded to the survey, and to whom the results of the survey can be generalized (Andrade, 2020) []. Thus, people with bias may be overrepresented in online survey samples, however, every effort was made to use appropriate, targeted equestrian social media groups and targeted wording in the recruitment requests. The survey findings may be skewed, because there is no way of knowing the motives of those who responded. There is no way of understanding the extent of bias in online surveys, but it is likely that those riders who suffer from chronic pain will be more motivated to respond to the survey and thus possibly over-represented. Responses may also be affected by social conformity. Whilst this study reports individual perception of pain and pain management, it is individual perception that is likely to determine the impact of the pain on that individual. This self-reported perception of pain limits the reliability of the results. A review of equitation research acknowledges research in this field is often hindered by small sample sizes due to access to participants (Pierard et al., 2015) [62]. The margin of error for this survey is 4.33% at 95% confidence level (using the number of horse-owning households in the UK). This suggests that the level of pain within the recreational and amateur competitive horse rider population is high (even at the lower limit of the confidence intervals, which are sometimes large). The findings within this study may have valid claims and be applicable to industry however future research should re-visit individual themes with larger sample sizes. This would reduce the risk of false positive assumptions common in small scale studies which lead to inaccurate associations being found or conversely, true associations not being reported.

Conclusion

As a result of performing yard duties’ this study shows an association with h recreational and amateur competitive rider populations reporting of high levels of pain. An hour or more of yard duties puts the participant three times higher risk of experiencing pain. This is of concern given how long a rider can participate in the activity of owning and riding horses, which can span several decades. This study highlights riders’ pain management strategies focus on self-medicating, potentially placing them at an increased risk of long-term health issues. it is essential that riders address any pain, postural or movement asymmetry and general functional movement deficits through exercises off the horse. Further research is needed to establish improvements in ergonomic tools for yard duties, training for correct lifting techniques and appropriate pain management strategies.

References

- British Equestrian Trade Association (BETA), 2023. BETA Equestrian Survey 2023.

- Dumbell L (2022) Profiles of British Equestrian Olympians: Evaluating historical, socio-cultural and sporting influences and how they could inform equestrianism in the future. (Doctoral dissertation, UWE Bristol).

- Ball CG, Ball JE, Kirkpatrick AW, Mulloy RH (2007) Equestrian injuries: incidence, injury patterns, and risk factors for 10 years of major traumatic injuries. The American Journal of Surgery 193(5): 636-640.

- Mayberry JC, Pearson TE, Wiger KJ, Diggs BS, Mullins RJ (2007) Equestrian injury prevention efforts need more attention to novice riders. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 62(3): 735-739.

- Sorli JM (2000) Equestrian injuries: a five-year review of hospital admissions in British Columbia, Canada. Injury Prevention 6(1): 59-61.

- Lewis V, Baldwin K (2018) A preliminary study to investigate the prevalence of pain in international event riders during competition, in the United Kingdom. Comparative Exercise Physiology 14(3): 173-181.

- Kraft CN, Urban N, Ilg A, Wallny T, Scharfstädt A, et al. (2007) Influence of the riding discipline and riding intensity on the incidence of back pain in competitive horseback riders. Sportverletzung Sportschaden: Organ der Gesellschaft fur Orthopadisch-Traumatologische Sportmedizin 21(1): 29-33.

- Lewis V, Nicol Z, Dumbell L, Cameron L (2023) A Study Investigating Prevalence of Pain in Horse Riders over Thirty-Five Years Old: Pain in UK Riders Over 35 Years Old. International Journal of Equine Science 2(2): 9-18.

- Lewis V, Kennerley R (2017) A preliminary study to investigate the prevalence of pain in elite dressage riders during competition in the United Kingdom. Comparative Exercise Physiology 13(4): 259-263.

- Lewis V, Dumbell L, Magnoni F (2018) A preliminary study to investigate the prevalence of pain in competitive showjumping equestrian athletes. Journal of physical fitness, medicine and treatment in sport 4(3): 555637.

- Williams J, Tabor G (2017) Rider impact on equitation. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 190: 28-42.

- Löfqvist L, Pinzke S (2011) Working with horses: An OWAS work task analysis. Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health 17(1): 3-14.

- Pugh TJ, Bolin D (2004) Overuse injuries in equestrian athletes. Current sports medicine reports 3(6): 297-303.

- Diem KG (2002) A step-by-step guide to developing effective questionnaires and survey procedures for program evaluation and research. Rutgers-Cook College Resource centre.

- Melzack R, Katz J (2001) The McGill Pain Questionnaire: Appraisal and current status. In D. C. Turk and R. Melzack (Eds.), Handbook of pain assessment The Guildford Press 7(3): 35-52.

- Fairbank JC, Pynsent P (2000) The Oswestry Disability Index. SPINE 25(22): 2940-2953.

- Bland JM, Altman DG (2000) The odds ratio. The British Medical Journal 320(7247): 1468.

- Krismer M, Van Tulder M (2007) Low back pain (non-specific). Best practice & research clinical rheumatology 21(1): 77-91.

- Davies E, McConn-Palfreyman W, Parker JK, Cameron LJ, Williams JM (2022) Is injury an occupational hazard for horseracing staff? International journal of environmental research and public health 19(4): 2054.

- Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Singh V, Benyamin RM, Fellows B, et al. (2009) Comprehensive Review of Epidemiology, Scope, and Impact of Spinal Pain. Pain Physician 12(4): 699-802.

- Balagué F, Mannion AF, Pellisé F, Cedraschi C (2012) Non-specific low back pain. The Lancet 379(9814): 482-491.

- Andersson HI, Ejlertsson G, Leden I, Rosenberg C (1993) Chronic pain in a geographically defined general population: studies of differences in age, gender, social class, and pain localization. The Clinical journal of pain 9(3): 174-182.

- Burbank KM, Stevenson JH, Czarnecki GR, Dorfman J (2008) Chronic Shoulder Pain: Part I. Evaluation and Diagnosis Am Fam Physician 77(4): 453-460.

- Cutlip RG, Baker BA, Hollander M, Ensey J (2009) Injury and adaptive mechanisms in skeletal muscle. Journal of electromyography and kinesiology 19(3): 358-372.

- Van Tulder M, Malmivaara A, Koes B (2007) Repetitive strain injury. The Lancet 369(9575): 1815-1822.

- Barbe MF, Barr AE (2006) Inflammation and the pathophysiology of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Brain, behavior, and immunity 20(5): 423-429.

- Majid M, Truumees E (2008) Epidemiology and natural history of low back pain. Seminars on Spinal Surgery 20(2): 87-92.

- Hsiang SM, Brogmus GE, Courtney TK (1997) Low back pain and lifting – A review.International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 19: 59-74.

- Gosheger G, Liem D, Ludwig K, Greshake O, Winkelmann W (2003) Injuries and overuse syndromes in golf American Journal of Surgery 31(3): 438-443.

- Dashper K (2014) Tools of the Trade or Part of the Family? Horses in Competitive Equestrian Sport. Society & Animals 22 (4): 352-371.

- McConn-Palfreyman W, Littlewood M, Nesti M (2019) A Lifestyle Rather Than a Job’: A Review and Recommendations on Mental health. Racing Foundation Report. A-lifestyle-rather-than-a-job.pdf (racingfoundation.co.uk).

- Douglas JL (2017) Physiological Demands of Eventing and Performance Related Fitness in Female Horse Riders (Doctoral dissertation, University of Worcester).

- Deckers I, De Bruyne C, Roussel N, Truijen S, Lewis V, et al. (2020) Assessing the functional characteristics of back pain in the equestrian. Comparative Exercise Physiology 17(1): 7-15.

- Lewis V, Douglas J, Edwards T, Dumbell L (2019) A Preliminary Study Investigating Functional Movement Screen (FMS) Test Scores in Female Collegiate Age Horse-riders Comparative Exercise Physiology 15(2): 105-112.

- Linton SJ (2000) A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine 25(9): 1148-1156.

- McNamee P, Mendolia S (2014) The effect of chronic pain on life satisfaction: Evidence from Australian data. Social science & medicine 121: 65-73.

- NEWC (2023) National Equine Welfare Council: Results of equine cost of living survey. Results of survey into impact of cost-of-living crisis revealed - National Equine Welfare Council (newc.co.uk)

- Molenaar B, Willems C, Verbunt J, Goossens M (2021) Achievement goals, fear of failure and self-handicapping in young elite athletes with and without chronic pain. Children 8(7): 591.

- Crane J, Temple V (2015) A systematic review of dropouts from organized sport among children and youth. European physical education review 21(1): 114-131.

- Maffulli N, Longo UG, Gougoulias N, Loppini M, Denaro V (2010) Long-term health outcomes of youth sports injuries. British journal of sports medicine 44(1): 21-25.

- Verhaak PFM, Kerssens JJ, Bensing JM, Sorbi MJ, Peters ML, et al. (2007) Medical help-seeking by different types of chronic pain patients. Psychology and Health 15(6): 771-786.

- Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D (2006) Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. European journal of pain 10(4): 287-333.

- Nixon HL (1993) Accepting the risks of pain and injury in sports: Mediated cultural influences on playing hurt. Sociology of Sport Journal 10: 183-196.

- Young K (2004) Sporting bodies, damaged selves: Sociological studies of sports-related injury. London: Elsevier.

- Cavallerio F, Wadey R, Wagstaff CRD (2015) Understanding overuse injuries in rhythmic gymnastics: A 12 month ethnographic study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 25: 100-109.

- Davies E, McConn-Palfreyman W, Williams JM, Lovell GP (2021) A narrative review of the risk factors and psychological consequences of injury in horseracing stable staff. Comparative Exercise Physiology, 17(4): 303-317.

- Volkmer K, Lucas Molitor W (2019) Interventions addressing injury among agricultural workers: a systematic review. Journal of agromedicine 24(1): 26-34.

- Hauret KG, Jones BH, Bullock SH, Canham-Chervak M, Canada S (2010) Musculoskeletal injuries: description of an under-recognized injury problem among military personnel. American journal of preventive medicine 38(1 Suppl): S61-S70.

- Jones McVey R (2021) An Ethnographic Account of the British Equestrian Virtue of Bravery, and Its Implications for Equine Welfare. Animals 11(1): 188.

- Figley CR, Roop RG (2006) Compassion fatigue in the animal-care community. Humane Society Press.

- Thomson P, Kibarska LA, Jaque SV (2011) Comparison of dissociative experiences between rhythmic gymnasts and female dancers. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 9: 238-250.

- Wadman M (2006) How does a painkiller harm the heart? Nature 441(7091): 262

- Riordan M, Rylance G, Berry K (2002) Poisoning in children 2: Painkillers. Archives of disease in childhood 87(5): 397-399.

- Ball CG, Ball JE, Kirkpatrick AW, Mulloy RH (2007) Equestrian injuries: incidence, injury patterns, and risk factors for 10 years of major traumatic injuries. The American Journal of Surgery 193(5): 636-640.

- Münz A, Eckardt F, Witte K (2014) Horse–rider interaction in dressage riding. Human movement science 33: 227-237.

- Wipper A (2000) The partnership: the horse-rider relation in eventing. Symbolic Interaction 23(1): 40-70.

- Watson AE, Pulford BD (2004) Personality differences in high-risk sports amateurs and instructors. Perceptual and motor skills 99(1): 83-94.

- Thompson K, McGreevy P, McManus P (2015) A critical review of horse-related risk: A research agenda for safer mounts, riders and equestrian cultures. Animals 5(3): 561-575.

- Wolframm IA, Williams J, Marlin D (2015) The role of personality in equestrian sports: an investigation. Comparative Exercise Physiology 11(3): 133-144.

- Galli N, Vealey RS (2008) “Bouncing back” from adversity: Athletes’ experiences of resilience. The sport psychologist 22(3): 316-335.

- International Society for Equitation Science (2024) 10 ISES Training Principles. ISES Training Principles (equitationscience.com). ISES Training Principles (equitationscience.com)

- Pierard M, Hall C, von Borstel UK, Averis A, Hawson L (2015) Evolving protocols for research in equitation science. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 10(3): 255-266.

- Baker BA (2017) An old problem: aging and skeletal-muscle-strain injury. Journal of sport rehabilitation 26(2): 180-188.

- Crook J, Rideout E, Browne G (1984) The prevalence of pain complaints in a general population. Pain 18(3): 299-314.

- Kettunen JA, Kvist M, Alanen E, Kujala UM (2002) Long-term prognosis for jumpers’s knee in male athletes American Journal of Sports Medicine 30(5): 689-692.

- Oakford G (2019) Yes Equestrians are Athletes! Yes, Equestrians are Athletes! | US Equestrian (usef.org). Accessed 23 March 2024.