The Effect of Fatigue and Upper Extremity Constraint on Lower Extremity Kinematics in Lacrosse Players

Katherine Woolley BA1, Ryan A Smith BS1, Richard Feinn1 and Karen Myrick M1,2

1Frank Netter School of Medicine, Quinnipiac University

2University of Saint Joseph, Connecticut, School of Interdisciplinary Health and Sciences

Submission:November 11, 2020; Published:December 21, 2020

*Corresponding author:Ryan A Smith, Frank Netter School of Medicine, Quinnipiac University, 370 Bassett Rd, North Haven, CT 06473, USA

How to cite this article:Katherine W B, Ryan A S B, Richard F, Karen M M. The Effect of Fatigue and Upper Extremity Constraint on Lower Extremity Kinematics in Lacrosse Players. J Phy Fit Treatment & Sports. 2020; 8(4): 555745. DOI: 10.19080/JPFMTS.2020.07.555745

Abstract

Background: Male lacrosse players have more ACL injuries than soccer players with an incidence of 0.17 per exposure [1,2,3]. Non-contact ACL injuries occur more often when recovery time is decreased. Methods: Fifteen male D1 NCAA lacrosse players were recruited. The constrained conditions were randomly assigned. Subjects completed a modified T-Test consisting of 8 non-fatigue trials with a stick (NFS) or without a stick (NFNS). Subjects then repeated trials until reaching a 5% increase in time compared to baseline. The following trials were collected as fatigue trials, all athletes carried a stick (FS). Hip and knee joint kinematics were recorded using a 10-camera motion analysis system at 32ms post initial contact (IC). A linear mixed effects model was used to determine the effects of upper extremity constraint and fatigue on hip and knee kinematics at IC. Post hoc multiple comparisons were performed using linear contrasts. Results: In the sagittal plane, subjects in the FS condition demonstrated a decreased hip angle (NFNS p<0.01, NFS p=0.03) and knee angle (NFNS, NFS p<0.01). In the transverse plane, there was a decreased knee angle in the FS subjects (NFNS p<0.01, NFS p<0.01). Finally, in the frontal plane, the FS condition had greater knee angles (NFNS, NFS p<0.01).

Keywords: Lacrosse; Arm constraints; Kinematics; Biomechanics; ACL; fatigue

Introduction

Non-contact ACL injuries are extremely common in sports with 100,000 to 200,000 ACL tears occurring each year in the US [4]. Cutting maneuvers that quickly change directions increase the risk for ACL injury by introducing anterior tibial forces that may strain the ACL.15 Male lacrosse players have increased ACL injury rates than soccer players with an incidence of 0.17 per athlete exposure [1,2,3]. Lacrosse players carry sticks and therefore have constrained upper extremities. This constraint may lead to alterations in lower extremity biomechanics, increasing the risk for non-contact ACL injury. Additionally, fatigue has been shown to play a role in increasing risk for ACL injury. An analysis of ACL injury found that there was a greater incidence later in the season and after halftime, indicating that fatigue may be involved.1 Another study found that there was an increased rate of injury in the second game in a week, further implicating that fatigued athletes are at an increased risk for ACL injury [5].

Arm swing is an integral part of human gait, it has been theorized to be essential in stability and efficiency [6]. Carrying a piece of sporting equipment may affect biomechanics. Chaudhari et al. found that arm constraint lead to significantly increased valgus load at the knee in lacrosse players, possibly increasing risk for non-contact ACL injury. Another study found that athletes holding a field hockey stick demonstrated greater hip extension and angular velocity at initial contact than non-constrained subjects. [7] Unrestrained upper extremity movement has also been shown to increase neuromuscular activation of the lower extremity when stepping [8,9]. Constraining the upper extremities may change the neuromuscular activity of the lower extremity and therefore the resultant kinetics and joint load. Additionally, having to carry something may decrease the focus of the athlete and may compound the effects of unanticipated movements. [10] Restraining the upper body creates reliability on the lower extremity responses to unanticipated movements, increasing an athlete’s risk for ACL injury. Heavy repetition has been shown to produce microscopic damage in the collagen fibers of ACLs in cadaveric knees. Similar molecular damage was found in ACL fibers of surgical patients at the time of repair. This indicates that repetitive use and fatigue may accumulate damage to the ACL tissue, placing the ligament at increased risk for rupture.6 Fatigue may also precipitate risk factors for ACL injury on a macroscopic scale. Fatigued athletes demonstrate decreased peak eccentric hamstring strength [11]. The musculature about the knee acts to dissipate the ground reaction forces (GRF). Decreased strength increases ligamentous load on the joint. This is highlighted in another study that investigated lower extremity kinematics in athletes that played two soccer games with only 43 hours of recovery between the games. Following the second game, athletes had significantly higher peak GRF, anterior tibial shear force, and lateral tibial shear force. All these factors place increased tension on the ACL and thus increase risk for injury [12]. Further research into the implications of upper extremity constraint and fatigue on lower extremity biomechanics may provide insight into noncontact ACL injury mechanics.

Materials & Methods

Subjects

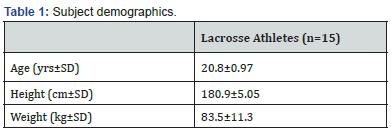

A convenience sample of 15 Division I collegiate lacrosse players between 18 and 22 years of age were recruited for participation in this study from June 2015 to June 2016 (Table 1). Eligible subjects were members of their Division I men’s varsity lacrosse team, free of injury at the time of enrollment, had no previous ACL injury, and were able to complete the agility test. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Procedures

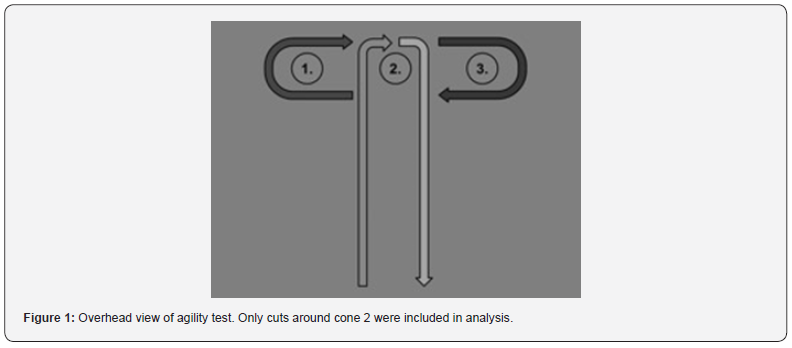

After establishing informed consent, subject demographics (age, height, and weight) were recorded (Table 1) and a past medical history obtained. Subjects warmed up on a treadmill for 5 minutes at a self-selected pace. Next, subjects completed 4 familiarization trials of the modified T-Test (Figure 1). Subjects performed two trials (one for each side) at maximum speed. Retroreflective markers were placed over specific boney landmarks on the subjects’ trunk, pelvis, and upper and lower extremities bilaterally using double sided adhesive tape (Figure 2). The subjects then commenced the agility testing protocol while kinematic data at 240Hz were collected.

Agility Testing Protocol

The subjects completed the modified T-Test in one of two conditions: non-fatigued carrying a stick (NFS), non-fatigued not carrying a stick (NFNS), these conditions were randomly assigned. All subjects then completed the course fatigued while carrying a stick (FS). The time to complete the course was recorded using a timing device.

Each subject completed 8 non-fatigue trials with or without a stick, alternating between performing a right and left turn (Figure 1). Subjects were afforded a 60 second rest period between trials to allow for full recovery. The average time plus 2 standard deviations to complete non-fatigue trials was determined and used as the fatigue criterion. The subjects then continued to perform the modified T-Test while carrying a stick with a 30 second rest interval in between runs until the subject failed to have two consecutive runs below the fatigue criterion. At this time the subject completed 4 additional runs (fatigue trails).

Data Analysis

The coordinate displacement histories of the retro reflective markers were obtained and filtered using a zero lag, 4th order, low pass Butterworth Filter with a 10Hz cutoff using a commercially available software package (Cortex, Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Barbara, CA). The leg making the cut and the type of cut were identified and recorded for each trial using the video data. The trunk and upper and lower extremities were modeled as an eleven-segment rigid body system with 10, six degree-of-freedom joints interspersed between the segments. A commercially available software package (KinTools, Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Barbara, CA) was employed to obtain the three-dimensional angular displacement histories for the hip and knee joints bilaterally using a Euler decomposition method (Z, Y, X). The stance phase of the extremity making the cut was extracted and the angular position of the hip and knee joints at 32ms post initial contact (IC) was determined. The time point 32ms post IC was chosen for analysis because previous evidence suggests that ACL injuries occur between 20 and 40ms post IC [13].

Statistical Analysis

A multi-level linear mixed model was used to compare the effects of stick carriage and fatigue on hip and knee kinematics at 32ms post IC. The trial condition with three levels (NFNS, NFS, FS) was a fixed effect and the intercept at the subject level and trial within subject were random effects. A significant effect for condition was followed by post-hoc paired comparisons to identify which conditions differed from the other conditions. Statistical significance was set at an alpha level of .05 and analyses were conducted in SPSS v.

Results

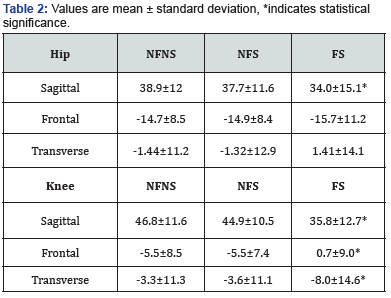

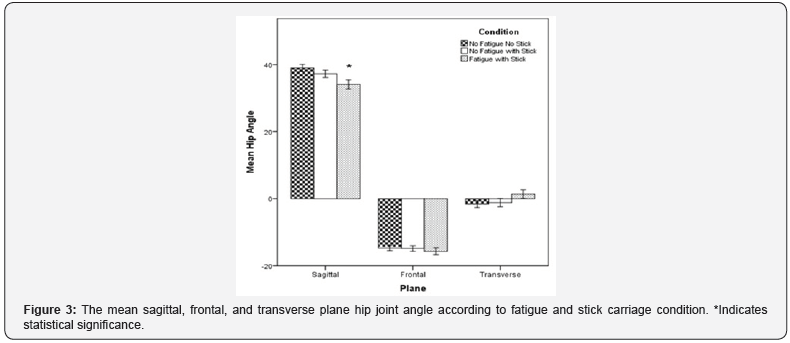

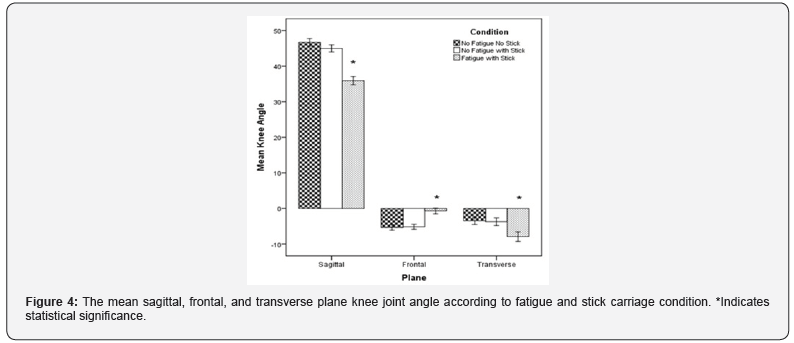

Table 2 shows the comparison of hip and knee kinematics in the NFNS, NFS, and FS states. There was a significant difference between the conditions at the hip in the sagittal plane (p=0.011) (Figure 3). Athletes in the FS condition demonstrated a significantly decreased hip angle in the sagittal plane as compared to the NFNS and NFS conditions (p=0.004, p=0.034). There was not a significant difference between the NFNS and NFS conditions (p=0.455). There was not a significant difference between conditions in the frontal plane (p=.736) or the transverse plane (p=.176). There was a significant difference at the knee between conditions in the sagittal plane (p<.001) (Figure 4). Athletes in the FS condition demonstrated significantly decreased knee angles as compared to the NFNS and NFS conditions (p<0.001, p<0.001). The NFNS did not differ from the NFS condition (p=0.224). There was also a significant difference between conditions in the frontal plane (p<0.001). The athletes in the FS condition experienced a significantly increased knee angle than the NFNS and NFS conditions (p<0.001, p<0.001). The NFNS did not differ from the NFS condition (p=0.963). Additionally, there was a significant difference in the transverse plane (p=.003). The FS condition had a decreased angle than the NFNS and NFS conditions (p=.004, p<.001). The NFNS did not differ from the NFS condition (p=.879).

Discussion

In this study, athletes displayed significantly extended hip and knee positions when fatigued and carrying a stick. Arm constraint made no significant difference in the non-fatigued state. A more extended hip and knee may place athletes at an increased risk for ACL injury. The extended knee increases shear force on the ACL. During isokinetic knee extension, the highest shear force at the ACL is experienced when the knee was extended past 60 degrees [14]. When the knee is extended, the quadriceps pull anteriorly on the tibia, increasing the tensile force on the ACL, and even increasing the length of the ACL itself [15]. Conversely, isometric hamstring and quadriceps contraction when the knee is flexed at 60 and 90 degrees does not increase ligament strain [16]. When athletes are running and cutting, the quadriceps are eccentrically activated. Electromyographic studies have found that this activation is twice more than maximum voluntary contraction [17]. Therefore, athletes that suddenly decelerate, and change direction with an extended position have increased shear stress on the ACL and may have an increased risk for injury. The FS trials displayed both extended hip and knee positions, indicating that fatigue and stick carriage may increase risk for ACL injury. The significant differences in lower extremity kinematics found in this study highlight the need for sport-specific arm constraints in ACL prevention or rehabilitation programs. Rehabilitation protocols tend to lack the inclusion of stick carriage, which does not allow the athlete to adopt protective kinematics and may not diminish risk of ACL injury [7]. Other studies have found that arm constraint leads to increased valgus load at the knee and increased hip extension [7,18]. Arm constraint has implications for single arm-constrained sports as well. Badminton players have increased rates of ACL injury in the knee opposite the racket-hand. Knee valgus moment at initial contact on a single-leg landing was significantly greater in the knee opposite the rackethand following an overhead stroke. Furthermore, it has been shown that moving the center of mass in the direction of cutting is protective of ACL strain and adverse joint loading. [19] Athletes may use their arms and trunks to manipulate the position of their center of mass in a cutting maneuver to alleviate ligamentous load. Athletes with constrained arms are not able to utilize this protective strategy and may experience the extended positioning seen in this study.

Another study investigating the effects of repetition and fatigue on lower extremity biomechanics found similar kinematic changes. Following a repeated 180 degree turn shuttle protocol, the subjects experienced a significant decrease in hip and knee flexion, like this study. Additionally, an increase in hip adduction and internal rotation was found.28 There have been similar results in fatigued stop-jump maneuvers. Fatigue was found to increase anterior shear force, valgus, and produce a more extended position at the knee [20]. These factors all increase the risk for ACL injury. The findings in this study are further supported by a systematic review with meta-analysis by Benjamin’s. This review found that the sagittal plane was the most effected by fatigue, leading to significantly extended hips and knees [21]. The extended knee positioning can be further explained by Whyte et al. who found that unanticipated cuts resulted in greater knee extensor activity. [22] Landing in an extended position means that less of the force is dissipated by the muscles of the lower extremity, increasing the impact on the ligaments. Another study found that fatigued subjects reached peak GRF significantly faster, possibly increasing the risk for ACL injury [23]. Additionally, fatigued athletes experienced increased GRFs and increased anterior tibial shear [12]. The extended positioning found in this study with fatigued athletes with arm constraints is supported by the literature and shown to potentially increase risk factors for ACL injury. This study adds to the body of literature by utilizing a dynamic cutting paradigm as opposed to a single leg land, and by constraining both arms with a lacrosse stick. This study may resemble gameplay more closely and may allow for further insight into how lower extremity kinematics in the fatigued and arm constrained state lead to increased risk for ACL injury.

One limitation of this study is the lack of electromyographic (EMG) analysis. EMG analysis of the lower extremity musculature may help determine a neuromuscular contribution to the observed differences in kinematics. Additionally, collecting data on fatigued athletes without upper extremity constraint may help differentiate the observed kinematic differences [24-28].

Conclusion

Fatigued athletes with arm constraints appear to cut with a more extended hip and knee position as compared to the nonfatigued state. Stick carriage did not make a significant difference in the non-fatigued state. This may place more load on the ACL and may contribute to the risk of non-contact ACL injuries in lacrosse players. Carrying a stick in combination with fatigue appears to place lacrosse players in a more extended hip and knee position that may place them at increased risk for sustaining non-contact ACL injuries.

References

- Mihata LC, Beutler AI, Boden BP (2006) Comparing the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injury in collegiate lacrosse, soccer, and basketball players: implications for anterior cruciate ligament mechanism and prevention. Am J Sports Med34(6):899-904.

- Gornitzky AL, Lott A, Yellin JL, Fabricant PD, Lawrence JT, et al. (2016) Sport-specific yearly risk and incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears in high school athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med44(10):2716-2723.

- Stanley LE, Kerr ZY, Dompier TP, Padua DA (2016) Sex Differences in the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament, medial collateral ligament, and meniscal injuries in collegiate and high school sports: 2009-2010 through 2013-2014. Am J Sports Med44(6):1565-1572.

- Gordon MD, Steiner ME (2004) Anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Orthopaedic knowledge update sports medicine III. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.3(1):169-181.

- Dupont G, Nedelec M, McCall A, McCormack D, Berthoin S, et al. (2010) Effect of 2 soccer matches in a week on physical performance and injury rate. Am J Sports Med38(9):1752-1758.

- Meyns P, Bruijn S, Duysens J (2013) The how and why of arm swing during human walking. Gait and Posture38(4):555-562.

- Wdowski MM, Gittoes MJ (2013) Kinematic adaptations in sprint acceleration performances without and with the constraint of holding a field hockey stick. Sports Biomech12(2):143-153.

- Ferris D, Huang H, Kao P (2006) Moving the arms to activate the legs. Exercise and Sport Science Reviews34(3):113-120.

- Huang H, Ferris D (2004) Neural coupling between upper and lower limbs during recumbent stepping. Journal of Applied Physiology97(4):1299-12308.

- Lorenz DS, Reiman MP, Lehecka BJ, Naylor A (2013) What performance characteristics determine elite versus nonelite athletes in the same sport? Sports Health5(6):542-547.

- Greig M (2019) Concurrent changes in eccentric hamstring strength and knee joint kinematics induced by soccer-specific fatigue. Phys Ther Sport37:21-26.

- Snyder BJ, Hutchison RE, Mills CJ, Parsons SJ (2019) Effects of two competitive soccer matches on landing biomechanics in female division I soccer players. Sports (Basel)7(11):237.

- Koga H, Nakamae A, Shima Y (2010) Mechanisms for noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: Knee joint kinematics in 10 injury situations from female team handball and basketball. Am J Sports Med38(11):2218-2225.

- Nisell R (1985) Mechanics of the knee, a study of joint and muscle load with clinical applications. Acta OrthopaedicaScandinavica56(216):1-42.

- Defrate LE, Nha KW, Papannagari R, Moses JM, Gill TJ (2007) The biomechanical function of the patellar tendon during in‐vivo weight‐bearing flexion.J Biomech40(8):1716-1722.

- Beynnon BD, Fleming BC, Johnson RJ, Nichols CE, Renstrom PA (2000) Anterior cruciate ligament

- Chaudhari AM, Hearn BK, Adnriacchi TP (2005) Sport-dependent variations in arm position during single-limb landing influence knee loading: implications for anterior cruciate ligament injury. Am J Sports Med33(6):824-830.

- Noyes F, Barber-Westin S (2018) ACL Injuries in the Female Athlete Causes, Impacts, and Conditioning Programs: Causes, Impacts, and Conditioning Programs (2nd) Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg: Springer189-190.

- Chappell JD, Herman DC, Knight BS, Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE, et al. (2005) Effect of fatigue on knee kinetics and kinematics in stop-jump tasks. Am J Sports Med33(7):1022-1029.

- Benjaminse A, Webster KE, Kimp A, Meijer M, Gokeler A (2019) Revised approach to the role of fatigue in anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Sports Med49(4):565-586.

- Whyte EF, Richter C, OʼConnor S, Moran KA (2018) Investigation of the effects of high-intensity, intermittent exercise and unanticipation on trunk and lower limb biomechanics during a side-cutting maneuver using statistical parametric mapping. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research32(6):1583-1593.

- Wwatanbe S, Aizawa J, Shimoda M, Enomoto M, Nakamura T, et al. (2016) Effects of short-term fatigue, induced by high-intensity exercise, on the profile of the ground reaction force during single-leg anterior drop-jumps. Journal of Physical Therapy Science28(12):3371-3375.

- Anderson T, Wasserman EB, Shultz SJ (2019) Anterior cruciate ligament injury risk by season period and competition segment: an analysis of national collegiate athletic association injury surveillance data. Journal of Athletic Training54(7):787-795.

- Chappell JD, Herman DC, Knight BS, Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE, et al. (2005) Effect of fatigue on knee kinetics and kinematics in stop-jump tasks. Am J Sports Med33(7):1022-1029.

- Chen J, Kim J, Shao W, Schlecht SH, Baek, SY, et al. (2019) An anterior cruciate ligament failure mechanism. Am J Sports Med47(9):2067-2076.

- Kiapour AM, Quatman CE, Goel VK, Wordeman SC, Hewett TE, et al. (2014) Timing sequence of multi-planar knee kinematics revealed by physiologic cadaveric simulation of landing: Implications for ACL injury mechanism. Clin Biomech29(1):75-82.

- Kimura Y, Ishibashi Y, Tsuda E, Yamamoto Y, Hayashi Y, et al. (2012) Increased knee valgus alignment and moment during single leg landing after overhead stroke as a potential risk factor of anterior cruciate ligament injury in badminton. British Journal of Sports Medicine46(3):207-213.

- Zago M, Esposito F, Bertozzi F, Tritto B, Rampichini S, et al. (2019) Kinematic effects of repeated turns while running. European Journal of Sport Science19(8):1072-1081.