Reliability of Parameters from Sport-Specific Method for Evaluating Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Performance

Rafael Penteado1*, Jason Gills1 and Fabrizio Caputo2

1 Center for Health and Sport Science, Santa Catarina State University, Brazil

2 Department of Sport and Movement Sciences, Salem State University, USA

Submission: January 30, 2020; Published:February 11, 2020

*Corresponding author:Rafael Penteado, Santa Catarina State University, Human Performance Research Group, Center for Health and Sport Science, Brazil

How to cite this article:Rafael P, Fabrizio C, Jason G. Reliability of Parameters from Sport-Specific Method for Evaluating Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Performance. 002 J Phy Fit Treatment & Sports. 2020; 7(4): 555719.DOI : 10.19080/JPFMTS.2020.07.555719

Keywords:Wrestling; Typical fight, High-intensity; Sex; Weight; Age; Technical level; Physical fitness; Short-range; Physiological; Jiu-Jitsu anaerobic; Butterfly sweep; Santa catarina; Gripping; Executant; Fitness

Introduction

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) is a martial art of ancient origin that has recently experienced a growth in popularity owing to its application in the sport of mixed martial arts, but also as a competitive sport. Jiu-Jitsu is a short-range, ground-based combat sport whereby the main objective is to control the body position of the opponent, like Olympic sports such as Judo and Wrestling. A typical fight can last up to 10 minutes for the elite division (i.e. adult black belt) and is characterized by intermittent high-intensity efforts intercalated by rest or lower intensity efforts periods. Tournaments are organized according to sex, weight, age, technical level (white to black belt), it is not uncommon that to be a tournament champion, the athlete must overcome a sequence of 3 to 5 fights during the day of the competition [1,2]. Despite the rapid growth and popularization of BJJ, the physical fitness of the practitioners is often assessed using non-sport specific tests including maximal isokinetic [3,4] running treadmill or cycle ergometer exercises to access VO2 [2]. Due to the short-range nature of this contact sport, the direct evaluation of physical demand by real-time monitoring is dangerous, even in controlled conditions (simulated fight), because even smaller wearable devices for measuring physiological responses might inadvertently cause injury. Considering the above factors, [5] developed a specific test for BJJ named the Jiu-Jitsu Anaerobic Performance Test (JJAPT). This test was aimed to assess the physical demand associated with Jiu-Jitsu performance by using the execution of a common technique known as “butterfly sweep”. The test protocol requires participants to perform a standard warm-up procedure followed by five consecutive all-out bouts of 1-minute duration, interspersed by 45-s passive rest. The authors identified an association between blood lactate concentration [LAC], obtained in JJAPT compared with a simulated Jiu-Jitsu fight. Based on these results, the author concluded that JJAPT could be an effective sport-specific test for BJJ practitioners. Nevertheless, reproducibility and measurement errors associated with this test remain unknown. The reliability of JJAPT is an important factor to confirm its sensitivity in accurately discriminating between BJJ athletes’ profiles such as, competitive and noncompetitive or beginners and advanced ones. In this way, JJAPT should be tested to identify measurement error related to the techniques itself, and variations associated with human-applied testing protocols. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to assess the reliability of the parameters of the JJAPT.

Methods

Design

A within-subject test-retest study design was utilized whereby the JJAPT was performed on three separate days (with 24-48 hours between trials). All testing were conducted at the athlete’s gym during their normal training sessions. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Santa Catarina University State Ethics Committee under protocol number 68041517.4.0000.0118.

Participants

In the present study 16 Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu practitioners were evaluated (8 Purple belts, 5 Brown belts, 3 Black belts, 23±19 yrs., 82.9±10.9kg, 1,75±0,15m). Participants had 8.0±5.0 years of training experience. During the season which the tests take place the athletes have weakly training 6.0±4.5h spread in 4.0±1.0 sessions per week.

Procedures

The JJAPT was performed following [5], being required for the participant perform the highest number of butterfly lift during five bouts of 1-min intercepted by 45-s passive resting. The athlete performing the butterfly lifts technique (executant) lays supine on the ground with his legs (knee at ~45º angle related to the floor) scooped between the legs of the second athlete (partner). The partner remains seated over executant’s legs, keeping their vertebral column straight. The movement sequence starts with the executant performing hip and knee flexion moving to a seated position, whilst wrapping his arms and gripping behind partner’s back (close to axilla’s region). The executant hands were clasped using a ‘gable grip’ with one hand in a pronated position and the other one in supinated position, whilst the executant’s thorax touched the partner’s thorax. In this exact moment, the executant returned to the lying supine position with knees flexed performing a kicking up motion (knee extension) reaching a ~90º angle related to the floor to project the partner over himself. Following this the executant flexed his knees and simultaneously brought his partner back to original position. Finally, the executant returned to his initial position (lying supine) with shoulders hyper-flexed to repeat the same movement cycle. Completion of the movement as previously described was considered as one completed cycle. To standardize the trials, participants performed a specific warmup that was composed of 30 jumping jacks; 15 squats; 15 hip escape motions (a BJJ specific technique); and 10 push-ups, and the same partner was keeping during all trials to minimize the load variation, on this study the variation on body mass of the partner was less than 0.5 kilograms (0.6% from average body mass participants). After five minutes rest from warmup, all participants performed the specific butterfly lift five times with a partner. On the first day of testing, the participants performed the JAPPT as a familiarization, on the next two days participants performed the test and retest respectively. From the JJAPT the following parameters were measured: Peak Score (PNBL) (i.e. the Peak number of butterfly lift repetitions); Lowest score (LNBL) (i.e. the minimal number of butterfly lift repetitions); Mean repetition score (MNBL) (i.e. the mean repetition of butterfly lift repetitions).

Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD) with 95% confidence intervals were used to represent centrality and spread of data. The variables were compared using paired two-tailed Student’s t test, which was used in the systematic error analysis. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the association between technical level (i.e. Belt graduation) and training background (i.e., training years and weekly training volume) and the parameters from JJAPT. The magnitude of difference between consecutive trials was also expressed as standardized mean differences (Cohen effect sizes [ES]). Effect sizes with values of <0.2, 0.2-0.6, 0.6-1.2, 1.2-2.0, 2.0-4.0 and >4.0, were considered to represent trivial, small, moderate, large, very large and extremely large differences, respectively. Appropriate performance usefulness indicators in accordance to the noise of the test result and measurement uncertainty was assessed via the magnitude of the SWC. Reliability of the change in the mean score between trials was determined using an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and typical error (TE), with typical error expressed as coefficient of variation (CV%). The ICC values of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9, and 1.0 were classified as low, moderate, high, very high, nearly perfect, and perfect, respectively. The following criteria was used to declare good reliability: CV<5% and ICC>0.69, according to (Hopkins, 2000). In order to determine any association between technical level (i.e. belt degree) and parameters, was used the Chisquared test, and the Spearman’s correlation was applied to check association between training session and training experience with parameters from JJAPT.

Results

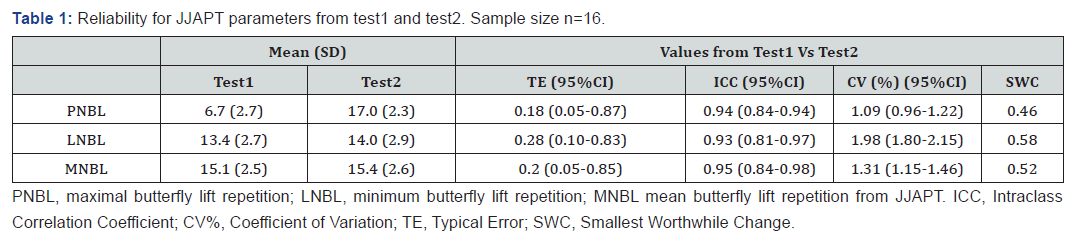

A pairwise comparisons results indicates no differences on PNBL, LNBL and MNBL (p= 0.312, 0.132 and 0.230, r= 0.894, 0.877 and 0.897) respectively. Further, the magnitude of difference for the outcomes between familiarization, test 1 and test 2 showed a trivial to small effect size calculated for PNBL, LNBL, MNBL (ES: 0.04, 0.07, and 0.05) respectively. No associations were found between parameters and technical level (Belt degree) under Chisquared test (p-value = 0.374). No correlation was found between the practice experience, number of training sessions per week and the JJAPT performance. Related to practice experience the Pearson’s correlation test revealed r and p values about (PNBL: -0.032, 0.907; MNBL: 0.124, 0.659 and LNBL: -0.355, 0.495). The same comparison between test performance and training sessions per week showed (PNBL: -0.229, 0.407; MNBL: 0.400, 0.138 and LNBL: -0.449, 0.903) r and p values respectively. The reliability values of the parameters from the JJAPT measured from trial 1 and trial 2 are displayed on Table 1.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the repeatability for specific parameters from JJAPT (i.e PNBL, MNBL and LNBL). The main findings from this study were that: The ICC above 0.93 and the TE less than one repetition for all the specific parameters, indicates that the JJAPT has “Good” reliability. In addition, the lack of differences between trials indicated the absence of a learning effect. Further analysis of the TE expressed as CV% data suggests that PNBL, LNBL and MNBL were highly robust measure, with all parameters having less than 2% of variation. The reliability and usefulness of each fitness test is a critical issue. There are two key criteria in establishing the usefulness of a test: the TE (the noise or error in the test) and the smallest worthwhile change in performance terms. If the TE is less than the smallest worthwhile change, then the test is rated as “Good”. If the TE is much greater than the smallest worthwhile change, then the test is rated as “Marginal”. If the typical error is about the same as the smallest worthwhile change then the test may be useful i.e. ‘OK’, particularly if repeated measurements (e.g. over a season) are averaged or inspected for trends over time. For the JJAPT and based on the sample size and characteristics from the present study all the parameters presented a “Good” level of usefulness. However, the smallest worthwhile change is about half motion cycle at which was impossible to be computed due to the motion execution criteria (i.e., knee extension reaching at least 90º angle related to the floor, during kicking phase). On that way the apparently reliability from the JJAPT parameters can resides on this very low resolution in terms of repetition accountability, therefore the realistic application of JJAPT could be questionable.

Another detail from this study is the fact of taking different skill level for the participants (i.e. belt level between purple to black and weight differences). Although this result could help to extend for a variety of Jiu-Jitsu practitioner, caution is still needed to talk about generalizations mainly for beginners. In the original paper [5] used only black belt competitors which probably contributed to the small standard deviation in the NBL scores (SD= 1.3 in each bout), compared to the present experiment. Thus, the higher standard deviations (~2.3 in each bout) observed in the present study suggest that technical level or physical fitness could affect the performance of JJAPT. While the performance parameters derived from JJAPT reported by Villar et al. [5] were also slightly higher compared to the present study corroborating with the previous assumption, no significant correlations were observed between technical level (i.e. belt graduation), practice experience (i.e. years of training), and number of training session per week with the JJAPT parameters in our more heterogeneous sample. The that lack of correlation between the variables may mean due the fact of the test be not sensitive to the different athlete’s profiles, indicating that JJAPT was not able to discriminate these characteristics.

However, this possible inability to screen fitness may be offset by the homogeneity in the physical fitness of Jiu-Jitsu practitioners. [1] have reported that aerobic power and capacity apparently are not influenced by athlete level (i.e., competitive or non-competitive athletes). Moreover, in the present study, it was not possible to properly discriminate the physical conditioning among the participants due to the lack of specific tests for that. To stratify the sample based on experience in years of training and on weekly frequency, it may be ineffective as a criterion for ascertaining associations with test performance [6,7].

Conclusion

Under the conditions of the present experiment it can be concluded that the JJAPT produces reliable measures of PNBL, LNBL, MNBL as evidenced by TE, ICC. Furthermore, to clarify the possible applications of JJAPT, the parameters need to be compared to other gold standard physiological measures, in order to determine the validity and sensitivity of the test as a performance predictor and/or to monitor training evolution.

References

- Andreato LV, Santos JF, Esteves JV, Panissa VL, Julio UF, et al. (2016) Physiological, Nutritional and Performance Profiles of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Athletes. Journal of Human Kinetics 53(1): 261-271.

- Leonardo Vidal Andreato, Francisco Javier Díaz Lara, Alexandro Andrade, Braulio Henrique Magnani Branco (2017) Physical and Physiological Profiles of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Athletes: A Systematic Review. Sports Med Open 3(1): 9.

- Follmer B, Franchini E, Diefenthaeler F, Dellagrana RA, Franchini E, et al. (2015) Relationship of kimono grip strength tests with isokinetic parameters in jiu-jitsu athletes. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria e Desempenho Humano 17(5): 575-582.

- Ferreira Marinho B, Vidal Andreato L, Follmer B, Franchini E (2016) Comparison of body composition and physical fitness in elite and non-elite Brazilian jiu-jitsu athletes. Science and Sports 31(3): 129-134.

- Villar R, Gillis J, Santana G, Pinheiro DS, Almeida ALRA (2018) Association Between Anaerobic Metabolic Demands During Simulated Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Combat and Specific Jiu-Jitsu Anaerobic Performance Test. Journal of strength and conditioning research 32(2): 432-440.

- Hopkins WG (2000) Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Medicine 30(1): 1-15.

- Vidal Andreato L, Javier F, Lara D, Andrade A, Henrique B, et al. (2017) Physical and Physiological Profiles of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Athletes: A Systematic Review Key Points. Sports Medicine 3(1): 9.