Review of The Currently Available Evidence for The Management of Metastatic Spinal Cord Compression Secondary to Breast Carcinoma

Ahmed Aljawadi1*, Mohammed Elmajee2, Mohammad Badr Almoshantaf3, Imad Madhi1, Mohamad Alqubaisi1, Mazin Alsalihy1, Noman Niazi1, Sudheer Akkena1 and Anand Pillai1

1Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Wythenshawe Hospital, UK

2Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Birmingham Orthopaedics Training Program, UK

3 Damascus Universty, Syria

Submission: September 25, 2019; Published:November 04, 2019

*Corresponding author:Ahmed Aljawadi, MBChB, MRCSEd, MSc Trauma and Orthopaedics, Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester, M23 9LT, UK

How to cite this article:Ahmed Aljawadi, Mohammed Elmajee, Mohammad Badr Almoshantaf, Imad Madhi, Mohamad Alqubaisi, Mazin Alsalihy, Noman Niazi, Sudheer Akkena, Anand Pillai. Review of The Currently Available Evidence for The Management of Metastatic Spinal Cord Compression Secondary to Breast Carcinoma. J Phy Fit Treatment & Sports. 2019; 7(1): 555704. DOI: 10.19080/JPFMTS.2019.07.555704

Abstract

Background: Spine is a common site of metastasis of many primary tumors (such as, breast, prostate and lung cancer) with metastatic spinal cord compression being one of the most common sequels of this. Many management options that can be used to alleviate symptoms of spinal cord compression and/or achieve stability of the spinal cord. However, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the best treatment strategies. The purpose of this essay is to discuss the available evidence for management of metastatic spinal cord compression, including initial protection of spine stability, corticosteroids treatment, surgery and radiotherapy

Methods and Results: A comprehensive literature search conducted to retrieve the most relevant articles that were published between 1994 and 2019. The search involved multiple search engines including PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Cochrane library. There is some evidence supports the administration of corticosteroids to alleviate the symptoms of cord compression, however side effects had been reported as an important issue. Surgery was considered the first management options for metastatic spinal cord compression in the carefully selected patients and could result in better outcomes than the other management options. Radiotherapy was associated with positive results. However, the best results were recorded when applying radiotherapy as adjunct after surgery.

Conclusion: Many factors should be considered when dealing with metastatic spinal cord compression, including symptoms, spinal stability, comorbidities, and patients’ preference. There was an evidence to suggest that surgery, in a carefully selected patient, may provide a better outcome compared to conservative measures.

Keywords: Breast cancer; Cord; Compression; Spine; Metastasis; Management

Introduction

Spinal metastasis is a frequently reported complication of malignant diseases [1]. It is one of the most devastating complications of malignancy [2]. The majority of symptomatic spinal metastasis are caused by breast, prostate or lung cancer [1]. The most common source of spinal metastasis in women is breast cancer, which accounts for approximately 21% of all cases of spinal metastasis [3]. Simultaneously, up to 75% of patients with advanced Breast cancer may have skeletal metastasis [4]. Spinal metastasis may cause vertebral pathological fracture causing pain, instability or compress the spinal cord or its dura covers [5]. Pain is usually the initial presentation, which is persistent and does not respond to treatment. Pain may be accompanied by neurological symptoms, such as sensory or motor neurological deficit [3,6]. Nevertheless, studies have shown that the diagnosis of spinal cord compression frequently occurs late in the progress of spine metastasis since the initial presentations including pain may not be well recognized [7]. However, Currently, there is no superior method in predicting survival [8]. The aims of management of spinal metastasis is to control pain, maintain stability of the spine, and prevent the development of neurological deficit [9,10]. According to Levack et al., it may be important to realize that the patient’s functional state after treatment is directly related to their functional state before treatment, which means when the patients lose their ability to walk prior to treatment, they are unlikely to recover post treatment [11].

Optimal treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach by the general practitioner, internist/oncologist/haematologist, radiotherapist, radiologist, neurologist and the spinal surgeon [12]. It’s concluded by Yang et al. that a better overall survival outcome might be achieved by a series of comprehensive and individualized treatments and personalized treatment [13]. The objective of this essay is to critically discuss the relevant evidence for management of MSCC. Different management options will be discussed including initial protection of spine integrity, corticosteroids treatment, surgery and radiotherapy. The search for the relevant evidence included several databases, which are PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Cochrane library. Different keywords are used to find the relevant literature including breast cancer, spinal cord compression, spine metastasis, management, radiotherapy, surgery and corticosteroids.

Conservative Management

Initial management maintain stability of the spine

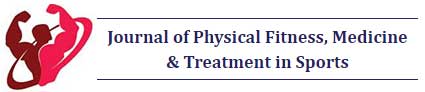

According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NICE (2008) [14], it may be important to protect the spine and spinal cord stability when managing a patient with Metastatic Spinal Cord Compression (MSCC). Consequently, any patient presented with a history of malignancy and new symptoms suggestive of MSCC including severe unremitting back pain should be managed initially by bed rest including lying flat till spinal integrity is ensured. Nevertheless, as the prolonged bed rest may be associated with increased risk of complications such as thrombotic events and chest infection, a Care Pathway was introduced by Pease et al. to facilitate management of patients with MSCC [15]. The aim of the application of care pathway is to allow early mobilization of patients with MSCC, it can help to improve early survival rate and preserve patient’s mobility [15]. However, the long-term survival time (after 78 weeks) reported by Pease et al. to be approximately the same (Figure 1) [15]. Even though [15] included a significant number of patients (148), which could increase the study reliability, however, the author reported that his study mainly involved comparison between two previous audits, which mainly involved retrospective analysis of patients’ data, thus providing a low level of evidence. In these patients, the spinal stability may need to be protected, and proper relevant history should be obtained to exclude any mechanical pain or neurological symptoms. Also, spine stability needs to be assessed by performing some relevant investigations such as x-ray or computed tomography (CT), as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) alone could not be enough to assess spinal stability [14].

Corticosteroids

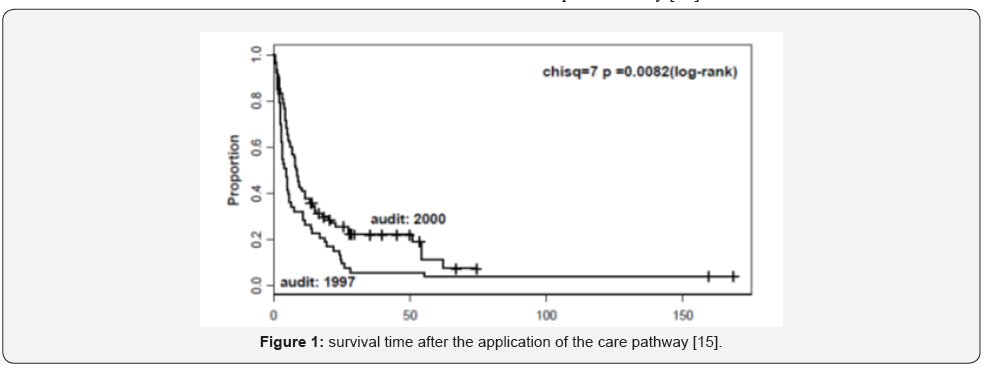

Corticosteroids is one of the options used for the management of MSCC. Corticosteroids can minimise the oedema around metastasis, reduce pressure on the spinal cord and it may help to relieve pain [16]. The effectiveness of high dose dexamethasone (96mg) as an adjunct to radiotherapy in the management of the patients with MSCC was evaluated in a randomised single-blinded trial conducted by [17]. In their study, the patients were randomised into dexamethasone plus radiotherapy (27 patients), and radiotherapy-only groups (30 patients). Improvement in ambulatory ability was observed in 81% of patients in the dexamethasone plus radiotherapy group, compared to 63% of patients in the radiotherapy-only group (Figure 2). Importantly, in this study, breast cancer was the primary source of tumors in 34 out of 57 patients, and thoracic spine were involved in around 58% of patients. However, the small sample size may decrease the study’s external validity. Finally, while this study is considered relatively outdated, it was included as there was a limited body of evidence assessing the role of corticosteroids in the management of MSCC. Likewise, Klimo et al. [18] performed a systemic review of the literature to review the efficacy of the different management options of MSCC [18]. The result stated that there was good evidence to support the use of corticosteroids in the management of MSCC patients. However, the study did not address clear inclusion and exclusion criteria regarding the patients’ initial presentation or previous history. Also, no information was available regarding steroids dose, duration or side effects, thus, the accuracy of the results might be affected. In a more recent evidence, a randomised trial performed by Graham et al. [19] compared high dose of dexamethasone (96mg) and radiotherapy versus low dose (16mg) with radiotherapy for the management of patients with MSCC [19]. However, the study was ended early due to inadequate recruitment of patients (only 20 participants were eligible for inclusion). The result showed that there was no significant difference in both outcomes and side effects, and their study could not yield statistically significant data.

As a summary of the main findings of the three studies mentioned above, it can be suggested that corticosteroids could be used for symptomatic relief in the management of MSCC. However, with the absence of high-level evidence studies, steroids side effects including gastrointestinal symptoms could be one of the limitations of corticosteroid treatment, although prophylactic measures such as proton pump inhibitors can be considered in conjunction with corticosteroids to protect gastric mucosa [19].

Scoring system – patients’ classification

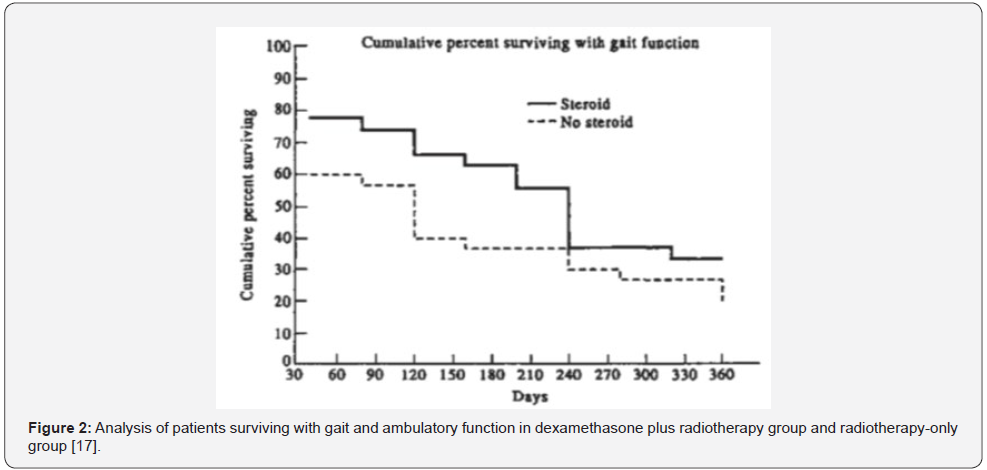

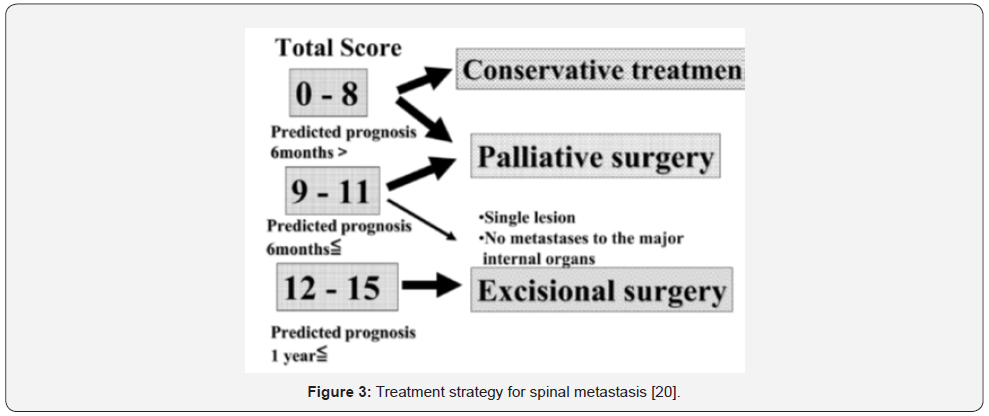

Before proceeding to discuss the role of surgery and radiotherapy in the management of MSCC, it would be necessary to examine the scoring systems, which help to choose the best management options. According to Levack et al. [11] severe back pain, with or without a characteristics of nerve root compression could be present for approximately 90 days before the diagnosis of cord compression in patients with MSCC [11]. As a result, any patient with a history of malignancy who develop spinal nerve root pain or severe back pain should be assessed urgently, as signs of metastasis may only occur in late stages of disease. Many scoring systems had developed to help predict the prognosis of spinal tumours and the appropriateness of the available management strategies. The Revised Tokuhashi Scoring System (RTSS) is one of the most commonly used for this objective. Tokuhashi et al. [20] performed a semi-prospective clinical study on 246 patients to assess the reliability of their revised scoring system in predicting prognosis of patients with MSCC [20]. The RTSS composed of six criteria with a total score of 15, (Table 1 & Figure 3). The rate of consistency between predicted prognostic and the survival rate after treatment was reported to be high (82.5%).

However, the main weakness of Tokuhashi et al. [20] study 20 is that asymptomatic patients were excluded from the study, which may cause a selection bias. Nevertheless, subsequent studies showed that the RTSS was useful to predict the patients’ prognosis and risks. For instance, two studies performed by [21,22] stated that the RTSS could have a significant high predictive value in predicting the prognosis of patients with MSCC. In their retrospective study, Ulmar et al. [21] found that there is a significant high predictive value in predicting the prognosis of 55 patients with breast cancer and spinal metastasis (p<0.0001) [21]. The use of a retrospective design could be considered as the main limitation of this study, consequently, the internal validity of the study could be reduced. On the other hand, Yamashita et al. performed a prospective observational cohort study (85 patients). Their study showed that the RTSS could be useful to predict survival of patients with spinal metastasis [22]. Nonetheless, to be able to apply the RTSS for patients with MSCC and back pain, other investigations may be requested to assess the presence or absence of extra-spinal bone metastasis and internal organ metastasis. However, depending on the RTSS and the evidence related to it, the surgical management may be considered first to relieve back pain of MSCC. The management option, however, should also consider the patient’s preference and surgeon opinion.

Surgery

A prospective study by Bouthors et al. [23] concluded that Surgical treatments helped to maintain reasonable condition for patients with spinal metastases and intervention should be offered before patients’ condition worsen to ensure better outcomes [23]. Additionally, a study conducted by Christoph et al. [24] discussed that surgery for spinal metastases (laminectomy, tumour removal, and mass reduction) significantly reduced pain as well as sensory and motor deficits [24]. So, for the management of MSCC, surgical option might be the best option that leads to actual relief of spinal cord compression and provides straightforward mechanical stabilisation of the affected part of the spine [25]. The indication for surgery in the management of MSCC is considered when there is a mechanical instability in the form of mechanical pain, impending or actual spinal cord compression in the form of relevant neurological symptoms, and if the pain fails to respond to conservative management [26].

Based on the results reported by a prospective cohort study performed by Mannion et al. careful selection of patients with MSCC for surgical management can achieve good quality of life and long-term survival [27]. The study assessed 62 patients with actual or imminent MSCC or cauda equina compression caused by different primary malignancies. The mean age of the participants was 62 years old and the thoracic spine was affected in 58% of patients. Median survival rate was around 13 months, ambulatory rate was increased from 68% before surgery to 80% after surgery, and patients’ quality of life was improved significantly. In fact, the different sources of primary metastasis could be the main issue with this study, because patients’ outcomes could be affected by the type of the primary disease.

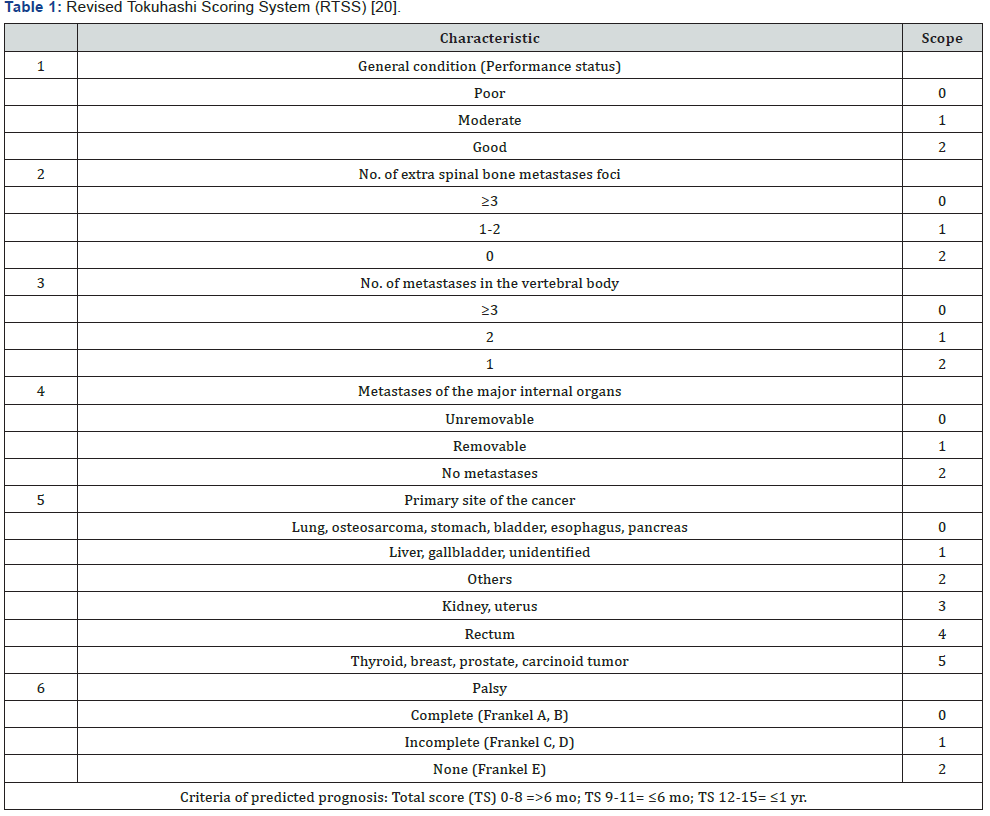

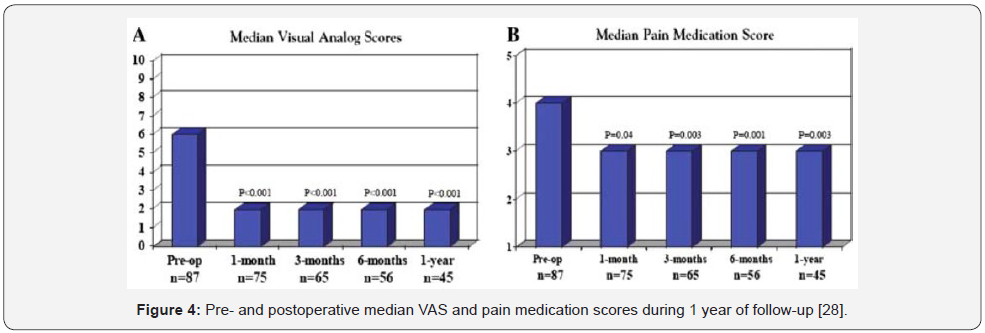

The effectiveness of surgery in the management of MSCC secondary to breast cancer was assessed by two studies: Shehadi et al. [28] conducted a retrospective study (87 patients) to evaluate the clinical outcomes after spinal surgery for patients with spinal metastasis secondary to breast cancer [28]. The median Visual Analogue Score (VAS) improved from 6 pre-operatively, to around 2 post-operatively with P value of less than 0.001, and the pre-operative median pain medication score was declined from 4 to 3 postoperatively (Figure 4). In approximately 50% of the patients, thoracic spine was the affected part by metastasis, and patients’ median age was around 53 years. Similar retrospective study assessing patients’ outcome after surgery for spinal metastasis from breast cancer was performed by [29]. In two-thirds of patients, the thoracic spine was the main affected part. The median survival rate was 1025 days, with best results recorded for patients who were able to mobilise early and who have not any complications postoperatively. Importantly, the small number of patients and the retrospective design of the study could be the main limitations of this study.

Excisional surgery

Excisional surgeries, including Debulking Vertebrectomy (DV) and En-block Vertebrectomy (EV), are among the surgical option used for the management of MSCC. The outcomes after excisional surgery for spinal metastasis were appraised by Li et al. [30] where 131 patients with spinal metastasis were grouped into 2 groups (32 patients were treated with EV and 99 patients were treated with DV) [30]. With a follow-up of at least 6 months impending, the patients’ survival period after EV was slightly higher than their survival period after DV. Although the study included a significantly large number of patients, the retrospective study design may limit the study internal validity. Additionally, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were not stated clearly. For instance, it was not clear whether patients with previous management were included or excluded, which could also affect the accuracy of the results. Finally, regarding the timing of surgery, it had been reported by Fürstenberg et al. [31] that the outcomes could be better if surgery was conducted within 48 hours of symptoms development [31].

To conclude, it can be assumed from the studies above that, it may be useful to perform the surgery when possible for carefully selected patients to manage MSCC before the development of any neurological signs, as once it develops, it may be difficult (if not unlikely) to repair. However, most of the studies above are retrospective studies with low evidence level, but there were only a few prospective studies assessing the surgical management for MSCC.

Radiotherapy

For patients with painful bone metastases, radiotherapy is an effective treatment, with a pain response rate of more than 60% [32]. Radiotherapy could be one of the treatment choices when the diagnosis of MSCC is made [33]. A meta-analysis by Klimo et al. [34] reported that ambulatory status was more improved after surgical management of spine metastasis than after radiotherapy (RT) [34]. However, Klimo`s analysis results could be of low level of evidence, as it depends mainly on a prospective or retrospective cohort studies. Moreover, in a randomised controlled trial by Patchell et al. [35] to determine the efficacy of surgery followed by RT versus RT alone for the patients with MSCC was conducted [35]. Participants were grouped into surgery followed by RT (group 1 of 50 patients), and RT alone (group 2 of 51 patients). It was reported that 84% of patients in group 1 were able to walk compared to 57% of patients in group 2 (P value of 0·01). Additionally, group 1 patients retained walking ability longer and consumed less analgesics than group 2 patients. Importantly, the main weakness of Patchell’s paper might be that the patients’ recruitment was highly selective. For instance, only patients with good prognosis and patients with a single area of spine metastasis were chosen, and this could be significantly different from patients who presented daily to spine clinics, which may affect the study reliability. In the same context, Kim et al. conducted a systemic review comparing the results of surgery with and without radiotherapy [36]. 64% of patients in the surgery group recover their ambulatory status compared to 29% in RT alone group, (p<0.001). Moreover, pain alleviation was more in patients received combined therapy than RT-only group (88% compared to 74%, respectively, p< 0.001). In fact, this systemic review assessed 34 studies with total number of patients equal to (2495), which is a significant number, but the main limitation could be that it included only 1 randomised controlled trial (RCT), while the others were case series, which might affect its evidence level. The summary of the main findings from the three studies mentioned above can suggest that RT may have a role in the management of MSCC. However, its effectiveness may be better noticed if it was given as adjunct with other management modalities (such as surgery), rather than given as a standalone option.

Regarding the effectiveness of RT doses and schedules, it was reported by Maranzano et al. [33] in their randomised multicentre trial, that there was no significant difference in response, the survival rate or the side effects between shortcourse RT (8 GY X 2) and long course RT (5 GY X 3; 3GY X 5) [33]. In another randomised, multicentre trial conducted by Maranzano et al. [37] it was reported that there was no significant difference between short-course RT (8 GY X 2), and single-dose radiotherapy (8GY) in terms of survival or radiotherapy side effects [37]. Based on the finding of these studies, it could be suggested that single-dose radiotherapy may be as effective as short course or long course RT for management of MSCC. However, Maranzano and his colleagues in both of their studies have included only patients with poor prognosis in their studies, which could affect the reliability of the study. Radiotherapy has remained the primary treatment modality for the management of metastatic spinal disease for the past three decades. Given its non-invasive nature, growing precision with advanced technology, and relatively rare adverse effects, radiotherapy will continue to play a large role for the foreseeable future [38].

Conclusion

The management options for MSCC depend on many factors, including spinal stability, presence of other morbidities, Clinical symptoms, and patient’s preference. Initial management can consider bed rest and corticosteroids. Many studies assessed the role of corticosteroids as a palliative management in patients with MSCC, and there was some evidence suggest its use in patients with spinal metastasis, but corticosteroids side effect should be considered as an important issue, especially with the absence of high-level evidence studies evaluating its role. On the other hand, with respect to the scoring systems, surgery could be considered as the first management option, as there was some evidence, although of low level, to suggest that surgical management for MSCC in carefully selected patients could be associated with better results. Furthermore, evidence showed that RT was associated with positive results for the management of spinal metastasis, however, the best results were recorded when RT was given as adjunct after surgery

References

- Bollen L, Jacobs W, Van der Linden Y, Van der Hel O, Taal W, et al. (2018) A systematic review of prognostic factors predicting survival in patients with spinal bone metastases. European Spine Journal 27(4): 799-805.

- Loblaw D, Laperriere N, Mackillop W (2003) A population-based study of malignant spinal cord compression in Ontario. Clinical Oncology 15(4): 211-217.

- McGovern SC, Fong W, Wang JC (2012) Metastatic spine tumors. Spine Secrets Plus: Elsevier, pp. 443-449.

- Lüftner D, Lorusso V, Duran I (2014) Health resource utilization associated with skeletal-related events in patients with advanced breast cancer: results from a prospective, multinational observational study. Springer Plus 3(1): 328.

- Clemons M, Gelmon K, Pritchard K, Paterson A (2012) Bone-targeted agents and skeletal-related events in breast cancer patients with bone metastases: the state of the art. Current Oncology 19(5): 259.

- Furlan JC, Chan KK-W, Sandoval GA (2012) The combined use of surgery and radiotherapy to treat patients with epidural cord compression due to metastatic disease: a cost-utility analysis. Neuro-oncology 14(5): 631-640.

- Witham TF, Khavkin YA, Gallia GL, Wolinsky JP, Gokaslan ZL (2006) Surgery insight: current management of epidural spinal cord compression from metastatic spine disease. Nature Reviews Neurology 2(2): 87-94.

- Kwan KYH, Lam TC, Choi HCW, Koh HY, Cheung KMC (2018) Prediction of survival in patients with symptomatic spinal metastases: Comparison between the Tokuhashi score and expert oncologists. Surgical oncology 27(1): 7-10.

- Abel R, Keil M, Schläger E, Akbar M (2008) Posterior decompression and stabilization for metastatic compression of the thoracic spinal cord: is this procedure still state of the art? Spinal Cord 46(9): 595-602.

- Sciubba D, Gokaslan ZL (2012) Surgery for Metastatic Spine Disease. Schmidek and Sweet Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results: Sixth Edition: Elsevier Inc: 2193-2199.

- Levack P, Graham J, Collie D (2002) Don't wait for a sensory level–listen to the symptoms: a prospective audit of the delays in diagnosis of malignant cord compression. Clinical Oncology 14(6):472-480.

- Baumfalk A, Verlaan J, Kasperts N, Amelink G, Minnema M, et al. (2019) Spinal metastases: early recognition and a multidisciplinary approach. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde 163.

- Yang SZ, Tang Y, Zhang Y, Chen WG, Sun J, et al. (2017) Prognostic Factors and Comparison of Conservative Treatment, Percutaneous Vertebroplasty, and Open Surgery in the Treatment of Spinal Metastases from Lung Cancer. World neurosurgery 108:163-175.

- National Institute for health and care excellence NICE (2008). Metastatic spinal cord compression: diagnosis and management of adults at risk of and with metastatic spinal cord compression.

- Pease N, Harris R, Finlay I (2004) Development and audit of a care pathway for the management of patients with suspected malignant spinal cord compression. Physiotherapy 90(1): 27-34.

- Cole JS, Patchell RA (2008) Metastatic epidural spinal cord compression. The Lancet Neurology 7(5): 459-466.

- Sørensen P, Helweg-Larsen S, Mouridsen H, Hansen H (1994) Effect of high-dose dexamethasone in carcinomatous metastatic spinal cord compression treated with radiotherapy: a randomised trial. European Journal of Cancer 30(1): 22-27.

- Klimo P, Kestle JR, Schmidt MH (2003) Treatment of metastatic spinal epidural disease: a review of the literature. Neurosurgical focus 15(5): 1-9.

- Graham P, Capp A, Delaney G, Goozee G, Hickey B, et al. (2006) A pilot randomised comparison of dexamethasone 96 mg vs 16 mg per day for malignant spinal-cord compression treated by radiotherapy: TROG 01.05 Superdex study. Clinical oncology 18(1): 70-76.

- Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Oda H, Oshima M, Ryu J (2005) A revised scoring system for preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine 30(19): 2186-2191.

- Ulmar B, Richter M, Cakir B, Muche R, Puhl W, et al. (2005) The Tokuhashi score: significant predictive value for the life expectancy of patients with breast cancer with spinal metastases. Spine 30(19): 2222-2226.

- Yamashita T, Siemionow KB, Mroz TE, Podichetty V, Lieberman IH (2011) A prospective analysis of prognostic factors in patients with spinal metastases: use of the revised Tokuhashi score. Spine 36(11): 910-917.

- Bouthors C, Prost S, Blondel B, Charles YP, Fuentes S, et al. (2019) Outcomes of surgical treatments of spinal metastases: a prospective study. Supportive Care in Cancer: 1-9.

- Hohenberger C, Schmidt C, Höhne J, Brawanski A, Zeman F, et al. (2018) Effect of surgical decompression of spinal metastases in acute treatment–Predictors of neurological outcome. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 52: 74-79.

- Prasad D, Schiff D (2005) Malignant spinal-cord compression. The lancet oncology 6(1): 15-24.

- Siddique I, Stirling A (2010) The surgical management of metastatic spinal cord compression. J Bone Joint Surg 92(8): 1054-1060.

- Mannion R, Wilby M, Godward S, Lyratzopoulos G, Laing R (2007) The surgical management of metastatic spinal disease: prospective assessment and long-term follow-up. British journal of neurosurgery 21(6): 593-598.

- Shehadi JA, Sciubba DM, Suk I, Suki D, Maldaun MV, et al. (2007) Surgical treatment strategies and outcome in patients with breast cancer metastatic to the spine: a review of 87 patients. European Spine Journal 16(8): 1179-1192.

- Walcott BP, Cvetanovich GL, Barnard ZR, Nahed BV, Kahle KT, et al. (2011) Surgical treatment and outcomes of metastatic breast cancer to the spine. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 18(10): 1336-1339.

- Li H, Gasbarrini A, Cappuccio M, Terzi S, Paderni S, et al. (2009) Outcome of excisional surgeries for the patients with spinal metastases. European Spine Journal 18(10): 1423-1430.

- Fürstenberg C, Wiedenhöfer B, Gerner H, Putz C (2009) The effect of early surgical treatment on recovery in patients with metastatic compression of the spinal cord. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume 91(2): 240-244.

- Westhoff PG, de Graeff A, Monninkhof EM, de Pree I, van Vulpen M, et al. (2018) Effectiveness and toxicity of conventional radiotherapy treatment for painful spinal metastases: a detailed course of side effects after opposing fields versus a single posterior field technique. Journal of radiation oncology 7(1): 17-26.

- Maranzano E, Bellavita R, Rossi R, De Angelis V, Frattegiani A, et al. (2005) Short-course versus split-course radiotherapy in metastatic spinal cord compression: results of a phase III, randomized, multicenter trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 23(15): 3358-3365.

- Klimo P, Thompson CJ, Kestle JR, Schmidt MH (2005) A meta-analysis of surgery versus conventional radiotherapy for the treatment of metastatic spinal epidural disease. Neuro-oncology 7(1): 64-76.

- Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, Payne R, Saris S, et al. (2005) Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomised trial. The Lancet 366(9486): 643-648.

- Kim JM, Losina E, Bono CM, Schoenfeld AJ, Collins JE, et al. (2012) Clinical outcome of metastatic spinal cord compression treated with surgical excision±radiation versus radiation therapy alone: a systematic review of literature. Spine 37(1): 78-84.

- Maranzano E, Trippa F, Casale M, Costantini S, Lupattelli M, et al. (2009) Gy single-dose radiotherapy is effective in metastatic spinal cord compression: results of a phase III randomized multicentre Italian trial. Radiotherapy and oncology 93(2): 174-179.

- Le R, Tran JD, Lizaso M, Beheshti R, Moats A (2018) Surgical Intervention vs. Radiation Therapy: The Shifting Paradigm in Treating Metastatic Spinal Disease Cureus 10(10): e3406.