Exploring Issues Faced by the Scottish Snowsports Industry: Interview Evidence

Kieran James1*, Toni Hanlon2, Xin Guo2 and Abeer Hassan2

1University of the West of Scotland, Scotland and University of Fiji, Fiji Islands

2University of the West of Scotland, Scotland

Submission: January 14, 2019; Published: January 29, 2019

*Corresponding author: Kieran James, University of the West of Scotland, Scotland and University of Fiji, Fiji Islands

How to cite this article: Kieran James, University of the West of Scotland, Scotland and University of Fiji, Fiji Islands 10.19080/JPFMTS.2018.05.555677

Abstract

This article aims to provide an insight into issues faced by the snow sports industry in Scotland including lack of snow caused by climate change and the difficulties associated with marketing to subcultures. Eight interviews with industry experts and enthusiasts were conducted, with seven key themes identified. Recommendations are made about how to improve marketing to the target markets given the unique importance of both transgressive and mundane subcultural capital in subcultures such as the ‘park rat’ snowboarders (a subculture which has traditionally been viewed negatively by the more middle-class skier segment within snow sports).

Keywords: Climate change; Global warming; Scotland; Scotland tourism; Snowsports; Snowboarding; Subculture; Subcultural capital

Introduction

General Introduction

The snow sports industry is of importance to the Scottish rural economy: the 2015-16 snow sports season saw 23,000 people hitting the slopes and brought in £21 million for Scotland’s rural economy Merritt [1]. The snow sports industry relies on snowfall, low winds, and dry conditions to create the perfect situation on the ground as sought after by skiers and snowboarders alike. However, the industry is threatened by global warming, with the Met Office’s prediction that the industry could disappear in Scotland in the next 50 years Cramb [2]. Snow days have fallen to as low as 15 days in recent years due to unfavorable weather conditions. Additionally, four of the five mountain snow centers in Scotland suffer from a lack of accommodation in the area, which results in a greater number of day visitors to the mountains in contrast to overnight visitors (Highlands and Islands Enterprise / Scottish Enterprise [3]. It is reported that, furthermore, “there are fewer younger people taking up the sport, fewer schools involved in skiing as an activity, due to costs, risk assessments and lack of staff volunteers” (Highlands and Islands Enterprise / Scottish Enterprise [3]. A declining level of interest in any activity by young people is worrying, as interest from this demographic is needed to secure the future of the activity.

The vulnerability of the winter season in Scotland has led to some of the resorts working on ways to attract visitors in the summer months. A strategic review carried out by Highland and Islands Enterprise / Scottish Enterprise [3] shows that mountain bikers spend roughly the same amount on the mountain as skiers and snowboarders do, a result making the development of this activity financially beneficial. The Cairngorms, one of the five resorts in Scotland, for example, has encouraged summer tourism through the addition of downhill mountain bike trails and the implementation of the U.K.’s only funicular railway. Previous studies in the area of geography highlight the risks that global warming has on winter tourism destinations. In the tourism field, prior research has analyzed statistics such as visitor days over the years and provided information on current and future market trends within winter tourism. A business approach to identifying issues and solutions could bring a new perspective, as little effort has ever been made to examine the Scottish resorts. Eight interviews were conducted in total with the eight respondents including six instructors; one marketing manager; and one customer care advisor. All interviewees worked in the snow sports industry in Scotland as at the dates of the interviews. In particular, the instructors provide valuable insights, as they work in the industry, they are passionate about the sport, and they know the sport. Working on the front-line, they create hype and push people to learn new things.

General Background

Scotland is home to five ski centers: The Cairngorms; The Lecht; Nevis Range; Glencoe; and Glenshee. The Cairngorms; The Lecht; Nevis Range; and Glencoe fall in the Highlands and Islands district, whilst Glenshee falls under Scottish Enterprise. Skiing was introduced into Scotland in 1956, when the first commercial ski lift was built at Glenshee. The industry has since developed into one of the biggest tourism sectors in rural Scotland, with approximately 70 chair lifts and tow lifts built across the five resorts. The first ever downhill ski race event in Scotland was held in 1936 on Beinn Ghlas Cox [4]. In the sixties, skiing was an activity only for the wealthy as it was an expensive activity; however, in the seventies, the boom in resort construction, infrastructure, and package ski holidays lowered the price for the activity, making it accessible to mainstream society (The Independent [5]. The graph below shows the number of ski days at each of the five Scottish resorts from 1986-2010 (source: Highlands and Islands Enterprise / Scottish Enterprise [3] (Figure 1).

Background to Snowboarding

In the early days of snow sports, only skiers were allowed to use the lifts as snowboarders were banned on most mountains. In 1985, only approximately 7% of resorts across Europe allowed snowboarders to use the resorts. By the nineties, most resorts had separate mountain areas for skiers and snowboarders. Currently, around 97% of the world’s mountains allow skiers and snowboarders on the same mountain. The reasons given for the original ban were beliefs that snowboarders would push snow off the mountain and that they were dangerous due to a blind spot Bulgariaski.com [6]. Snowboarders are known as the rebels; the outcasts; the undesirables. The banning of snowboarders amplifies the rebellious nature of snowboarders and creates the stereotypes and opinions of snowboarders. The negativity directed towards snowboarders has helped create and preserve a unique subculture within snow sports. The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a theoretical framework (subcultural capital); Section 3 reviews the extant literature; Section 4 describes the methods used in the study; Section 5 presents research findings; while Section 6 concludes the article and provides recommendations.

Theoretical Framework - Subcultures and subcultural capital

The Oxford Dictionary defines subcultures as “a cultural group within a larger culture, often having beliefs or interests at variance with those of the larger culture”. Subcultures are individual cultures within a parent culture. They are minority groups with a common culture (e.g. race, religion, political, a love for an activity, or an art form such as skateboarding or music) De Burgh‐Woodman and Brace‐Govan [7]. Some commentators, such as Keith Kahn- Harris [8,9] who has written and published extensively on the Extreme Metal Music scene, prefer the term ‘scene’ to ‘subculture’. However, Kahn-Harris still uses the term ‘subcultural capital’ (which he divides into two categories: the ‘transgressive’ and the ‘mundane’) because it draws upon Pierre Bourdieu’s [10,11] preexisting concept of ‘cultural capital’ and was used earlier by Sarah Thornton [12] in her study of youth cultures that revolve around dance clubs and raves in Great Britain and the U.S.A. According to Kahn-Harris [8,9,13] to gain respect within a subculture, and to receive maximum enjoyment from one’s participation in the subculture, a person must accumulate sufficient transgressive and sufficient mundane subcultural capital. The ‘transgressive’ Coggins [14] is obvious (church-burnings by satanic Black Metal bands in Norway over the 1992-1994 period is a classic example) but the ‘mundane’, equally as important, accumulates for people who are honest and transparent in business dealings within the subculture and maintain the existential sincerity of sticking to one belief system, worldview or way of presenting oneself. (An example would be a band with Death Metal sound and aesthetics sticking to them consistently over the years rather than following trends).

All of our eight interviewees possess significant subcultural capital within the snow sports industry or scene. We retain the use of the familiar term ‘subculture’ here whilst acknowledging the worth and importance of Kahn-Harris’ [8,9] contributions to the literature. Subcultures are perceived as a deviation from normalcy. They operate beneath the surface of mainstream society and are often perceived negatively as rebellious or of the lower-class (although these attitudes are changing to a certain extent at least with respect to non-violent subcultures). Many subcultures have spread throughout the world, even to the most unlikely and remote places, as authors such as Baulch [15,16], James and Walsh [17], forthcoming); and Wallach [18,19] have demonstrated with respect to the Indonesian Extreme Metal Music scenes. De Burgh‐Woodman and Brace‐Govan [7] suggest that a good understanding of subculture participants and their consumption habits is required to market to them successfully.

Literature Review

Winter Tourism

Prior research focuses on climate change as the main area of concern, rather than ski resort users’ attitudes towards the changing environment. Many studies were conducted in countries in the Alpine region, which is highly dependent on snow sports to bring in millions to their tourism industries. However, these mainland or continental European countries have seen a decline in ski days in recent years because of poor weather conditions Gössling [20]. As the Scottish snow sports industry faces the same climate change concerns, the extant literature concerning snow sports in mainland European destinations is relevant to this article. Austria, for example, experienced a weak season in 2006-07 due to poor weather conditions, with profits reducing by €12.1 million. Studying six ski resorts in Austria, Unbehaun [21] identified three strategies implemented at all the resorts: (a) adapting measures to secure snow-based winter sports tourism (e.g. artificial snow-making, extensions in higher altitudes, and expansion in glacier areas); (b) compensating clients in situations with insufficient snow (e.g. additional winter activities) to maintain visitors’ loyalty; and (c) developing alternative tourism strategies (e.g. investment in four-season-tourism especially strengthening the summer season).

Scottish resorts also make use of snow cannons. During the summer season of our interviews (2016/2017), Scotland had 15 ski days at some of the lower resorts compared with 60 ski days during the same time interval the previous year Merritt [22,23]. The cannons are now vital pieces of equipment to ensure the opening of the mountain resorts. For the snow sports industry, other weather conditions including high winds and rain, also cause concern for the snow sports industry. High winds cause concern about the safe running of chair lifts; while rain affects the amount and quality of snow on the mountains Merritt [22,23]. Seasonal tourism can struggle to generate sufficient cash flow throughout the year, as most of the income is generated in just one-quarter of the year. Ensuring income throughout the year will boost the Scottish rural economy and balance out bad winter seasons. The Cairngorms, for example, has made such efforts with the addition of downhill mountain biking tracks. Highlands and Islands Enterprise / Scottish Enterprise (2011) reports that the average daily spend of a downhill mountain biker was £21.50, compared with £22.85 for a skier or a snowboarder (which is essentially the same daily spend).

Winter Tourist Motivations

Prebensen & Lee [24] suggest that tourist motivations be better understood to ensure successful marketing campaigns. Different from other tourists, winter tourists have to consider the impact of climate change, which can change their perceptions of the attractiveness of winter sports destinations (e.g. snow quality).

Push and pull factors

The past literature suggests that push factors are the internal motives of individuals to meet their needs; whereas pull factors are generated through the attractiveness of a destination. Push factors are useful in identifying the desire to travel; whilst pull factors help with understanding why tourists choose a particular destination. Crompton [25] argues that the motives for pleasure tourism fit into the idea of ‘a break from routine’, with a high importance placed on the social aspects of travelling. Crompton (1979) further identifies seven socio-psychological motives for pleasure tourism: (a) escape from a perceived mundane environment; (b) exploration and evaluation of self; (c) relaxation; (d) prestige; (e) regression; (f) enhancement of kinship relationships; and (g) facilitation of social interaction. Events including festivals often act as a pull factor in winter tourism, for example, ‘Groove’ at the Cairngorms, the first resort-based snow sports festival held in the U.K. in 2016. The event acts as a pull factor, as multiple activities can be enjoyed at the event by young people looking for new and exciting experiences.

Marketing Strategy

The Chartered Institute of Marketing (CIM) [26] defines marketing as “the management process responsible for identifying, anticipating, and satisfying customer requirements profitability”. Furthermore, Holloway [27] suggests that “marketing is about anticipating demand, recognizing it, simulating it and finally satisfying it; in short, understanding consumers’ wants and needs, as to what can be sold, to whom, when, where and in what quantities”. Most of the ski resorts in Scotland are operated by small and medium enterprises (SMEs), one exception being the Cairngorms, which is owned by ‘National Retreats’, a global tourism company. Robinson [28] suggest that “a compilation of data surrounding market trends, visitor profiles and industrial impacts, combined with a strategic overview of the market, will provide businesses with the tools needed to develop a competitive advantage.” One method of gaining a strategic overview is to complete a SWOT analysis, a strategic planning method used in marketing to identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT). For this article, a SWOT analysis was conducted for the snow sports industry in Scotland see Table 1.

Marketing to Subcultures

Subcultures are perceived as a deviation from normalcy. They operate beneath the surface of mainstream society and are often perceived negatively as rebellious or of the lower-class (although these attitudes are changing to a certain extent at least with respect to non-violent subcultures). De Burgh‐Woodman and Brace‐Govan [7] suggest that a good understanding of subculture participants and their consumption habits is required to market to them successfully. Known as ‘Park Rats’, Freestyle and slopestyle riders are not seen as attractive to market and are not perceived to be the big spenders on the mountains [29]. However, there is a large community of loyal riders when given a park to play on. This view resembles the perception that subcultures are viewed as lower classes. This article holds that the ‘Freestyle Subculture’ is a missed opportunity for marketers in the industry, with further research required to understand the consumption habits of this group to be able to market to them effectively.

Research Method

This article aims to provide an insight into issues faced by the snow sports industry (defined as skiing plus snowboarding) in Scotland, with semi-structured interviews being conducted.

Interviewees

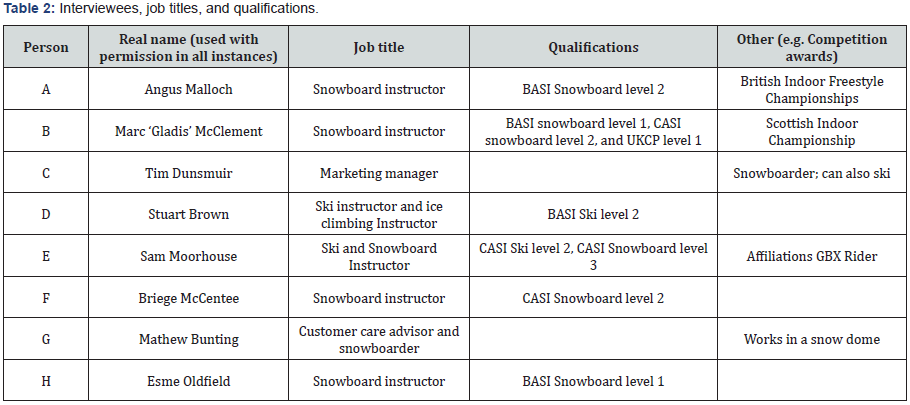

Eight interviewees were chosen as they were highly knowledgeable about the snow sports industry in Scotland. The interviewees’ job titles and qualifications are provided in Table 2. (To provide an informed response, it was important to ensure that the interviewees could ski or snowboard and had a passion for the industry).

Notes:

BASI: British Association of Snowboard Instructors.

CASI: Canadian Association of Snowboard Instructors.

UKCP: U.K. Coaching Pathway.

Conduct of Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted. The interviewees were informed of the research objectives. The interviews were audio-recorded upon permission. All the interviewees were assured of confidentiality and anonymity. The interviewees were informed that the research is industry-wide, to refrain from negativity toward individual businesses. Interviews questions were designed to keep the interviewees focusing on the whole industry rather than upon their workplaces.

Data Analysis

The interviews were transcribed and analyzed, with seven themes (i.e. issues) identified. Research findings are reported in the next section.

Findings

Through data analysis we were able to identify seven key themes:

i. Background and influences

ii. Weather

iii. Subculture

iv. Tourism motivations

v. Marketing

vi. Employment (job opportunities and security)

vii. Young people

Background and Influences

Most of the interviewees had been involved in snow sports since an early age. Many were encouraged into snow sports by their parents who were keen skiers.

“I started when I was three in skiing up at Glenshee where my dad worked, so it was nice and easy. I continued through started racing and then went to Sölden. When I was around seven, I wanted to try snowboarding, saw it always up at Glenshee always wanted to try it even though my dad was always like ‘no you cannot try it; that is the devil!’ you know…gave it a shot fell in love and just kept going; continued skiing until I was 12 but like on and off skiing to snowboarding, …never got taught, taught myself, never got trained, trained myself when I was 12; just continued snowboarding; never set onto a pair of skis after that…learned about freestyle through White lines magazine; it was the ones where you got like the DVD with the magazine” (Interviewee A).

The White lines magazine was mentioned by Interviewee A and all other interviewees. It is interesting to note that one physical-copy magazine had such a strong influence. When asked what motivated him to choose snowboarding, Interviewee B stated:

“It was more the freestyle side of things like it was just the… because I BMX’ed and skateboarded when I was younger; just having that and doing tricks and going to a skate park. It just felt better. It felt more fun. It felt more exhilarating. It felt more interesting” (Interviewee B).

Interviewee D skied, as his parents wanted him to do, but it quickly became about his competitive nature even as a child for him, an attribute often associated with ski racers. It was noted that he was driven by competition, with his passion being not as evident as other interviewees. This could be due to the nature of skiing: skiing and specifically ski racing are known to be more regimented than snowboarding, causing the drive to win but a lack of enthusiasm for the sport, as it becomes more about training than having fun:

“Been skiing since I was three; kinda had no choice my dad was a fairly keen skier, he started self-teaching us up to a point... Then went to Bella Houston where we done [sic] further lessons so I would say I was about six or seven when we started going there and it got to the point he [the interviewee’s father] became an instructor because we were catching up with him. He went through his instructor qualifications…he saw fit for me to start doing the qualifications, kind of as a backup that, if I was ever struggling for work, I would have something to fall back on. So, I have been a qualified instructor since 16; started teaching here in 2010 so coming up for seven years now [of] teaching experience…” (Interviewee D).

When asked about his background, Interviewee G was the only interviewee to learn snowboarding at school:

“I snowboard and kind of ski, I started snowboarding lessons about 12 years ago when I was 12 back in school because Sam told me to start snowboarding. I had done ski lessons before that through school. I gave that up and changed to snowboarding” (Interviewee G).

Most of our interviewees had similar attitudes when describing why they snowboarded, as they labelled themselves ‘adrenaline junkies’, who spent all their free time doing an extreme sport; they wanted to try something new, and then craved it like an addiction. Sponsorship is often achieved at an early age when a young rider shows potential: this development can be life-changing for that individual. The sponsorship provides funding, equipment, and promotion for the rider. The sponsorship usually comes from snow sports clothing and equipment brands and is particularly significant on the freestyle side of snowboarding. Prior research has suggested that it becomes harder to involve young people into the sport. When asked what could be done to encourage young people into snow sports in Scotland, Interviewee B pointed out:

“I have always thought that, for instance, Snow Factor could go to schools, speak about it, try and get [them] interested. Stuart Brown [Interviewee D]’s dad has a portable ski slope that goes in the back of his trailer, folds out, goes around schools to get them to try skiing, would be pretty expensive to do. Getting people into it, there needs to be more community outreach as well. One of the coolest things that I ever saw that kind of helped spark me into snowboarding, I saw a street rail setup in town where they setup rails from Snooze back in the day, they setup rails in town and like had a drop in and everything, it was so cool, I was 11 or 12” (Interviewee B).

Most interviewees recalled the first time they saw someone on a snowboard doing tricks, which sparked a deep desire to snowboard themselves. Young people appear to respond to things that are exciting, fun, and cool. Street set-ups were ideal for getting the required attention as promoters were getting it to young people in a physical form.

Weather

All of the interviewees identified that the snow in Scotland is nowhere near the standards of snow in international resorts, for example, in mainland Europe or Canada. Some interviewees identified the frustration they faced this year (2016-17 season): they were not able to get up to the mountains this year as much as they used to because of the weather. This affected job security in the snow sports industry in Scotland.

“Snow! Snow is the number one aspect. Like right now we are in January [2017], we have no snow…It is only arriving this week where[as], before last year, we [often] had snow in November. It went away then came back in December. So, it is the snow that dictates if you have employment or not; it is not to do with companies; it is not to do with the resorts or the mountains or anything like that” (Interviewee A).

“The whole industry; it is weather dependent; that is just a fact and it’s particular conditions [which are] needed to create good snow and lots of it. What screws Scotland the most is wind because we are an island; it just blows all the snow off and that is something that we cannot do anything about” (Interviewee B).

There was a concern that there would be a decline in the number of regular customers who are vital assets to the industry. These customers provide consistent and reliable cash flows into the businesses; discuss the businesses with other snow sports participants; and promote the businesses in the most sincere and authentic fashion. The interviewees also identified a decline in customer numbers in the indoor slope in Glasgow in the summer (2016-17), even though the facility was not affected by weather at all. One explanation could be that, in the summer, people have a different frame of mind in that they want to do something in the heat, especially Scottish people. Snow, furthermore, is not the only issue. It is common for resorts to have adequate snow, but winds are too strong to operate the lifts safely. As weather can hardly be controlled, resorts and businesses in the snow sports industry should consider what activities they offer and how quickly the activities can be arranged.

“I think the most important issue just now is the unreliability of it [snow and otherwise good conditions] in Scotland; it is really kind of unpredictable, for the resorts a bad season like this could spell the end for a resort like Glencoe if they did not have anything to see them through. If they did not have the summer mountain biking it would be really difficult” (Interviewee D).

Subcultures

When asked about working experience in the snow sports industry, Interviewee A stated:

“You know seeing progression, (in Britain anyway) it is changed dramatically; it is gone from like, back when I first started, snowboarding was still like the rebel thing; no one wanted to know you, no one; thought you were a hooligan; didn’t want to have you on their slope and anything like that so, and that was the kind of thrill as well, people kind of saw you as an outlaw; it was the cool thing but it did not matter; I just wanted to snowboard; I did not give a f*** to be honest. Through, not generations but through the years, it…slowly came off of that and actually became something [more acceptable]” (Interviewee A).

Interviewee A talked about being labelled a ‘hooligan’ and a ‘rebel’ because of snowboarding. The literature review identified subcultures as ‘undesirables’, ‘outsiders’ and ‘trouble-makers’ in many people’s perceptions. Interviewee A was not the only interviewee to talk about how snowboarding had been viewed by society. In the past ski-only resorts were more commonplace; however now very few resorts are currently ski-only resorts with Alta being the most notorious regarding the issue.

When asked to describe typical snowboarders and typical skiers, Interviewee D commented as follows:

“Snowboarders: A lot more laid-back with baggy clothes, dreads, calling everyone dude. A bit less technical, more about having fun, more about enjoying the sport and doing the sport because it is fun; not doing the sport because it is a job and a whole lot more laid-back atmosphere during lessons; and when you are snowboarding in general it is all about enjoyment” (Interviewee D).

All interviewees gave very similar replies to this question about ‘typical’ skiers and snowboarders, with the attitude difference identified between skiers and snowboarders. Snowboarding stuck out more as the subculture within snow sports when considering this. The literature review has suggested that subculture participants often wear identifiable clothing so that they can be recognized as a subculture; although there are also similar descriptions for skiers, respondents tended to identify skiing with a ‘ski racer’, known as ‘strict’, ‘competitive’ and ‘regimented’, but also known to be way more mainstream which can be seen in her/his purchasing habits and skiing’s status as an ‘Olympic sport’. Interviewee D identified that “the stereotypical skier stands out a mile because it is all the flash gear and the expensive Spyder [brand] stuff that cost them £400 but is not actually a good jacket”. These types of skiers were stereotypically seen as middle-aged with disposable income; skiing was seen as a holiday once or twice a year in big resorts and less a lifestyle or passion.

However, when the discussions delved deeper into the distinctive styles of skiing and snowboarding, the picture changed. ‘Freestyle skiers identified more with freestyle snowboarders than with any other style. Most interviewees agreed that there was not much of a difference between freestyle skiing and snowboarding; Interviewee A stated that freestyle skiers were often perceived to be more extreme in their clothing.

“You go into the skiing side, and then you get like freestyle skiers and jibbers and they are even worse than snowboarders. They are like mad tees that go down to their ankles with their trousers down at their ankles with braces holding them up over their shoulders” (Interviewee A).

The interviewees’ attitudes towards brands differed depending on the style of snowboarding and skiing that she/he does, but the attitude of a freestyle rider towards brands identifies more closely with the characteristics of a subculture than any other style of skiing or snowboarding, often displaying strong brand loyalty to the brands that ‘speak’ to them (usually on an ethical level):

“...not a lot of people know about them they are called Dinosaurs Will Die, named after the [Southern Californian skate-punk band] NOFX[‘s] song ‘Dinosaurs will die’. They are my favorite brand because of their ethics towards snowboarding; they are a very underground brand; they are getting bigger and bigger through popularity because of their…ethics towards snowboarding in a way; the guy who owns the company is known as like one of the nicest guys in the industry. Their slogan is ‘by riders, for riders’, you know the people who make their boards and design their boards are the people who ride for the company and film for the same video parts” (Interviewee E).

Interviewee B, furthermore, highlighted the importance of marketers within the industry who have a genuine passion for snow sports themselves:

“Well, if you live and breathe something, it is so easy to sell it because you do not have to make up a passion; you already know what to say and how it should be portrayed. Because it is a definite style within snow sports that is a bit different and it is different within the snow sports industry itself; because there is like racers, your casual everyday skier, your ‘jerry’ beginner who [has] never done it before, your park rats, people who just want pow, and there is all kind of separate demographics within themselves, they can be made up of 25- to 50-year-olds; it does not have to be a specific age group…thing; it is just random” (Interviewee B).

The Interviewee B quote (above) highlights the importance of using the correct terminology when marketing within the industry (and this is where the ‘business-school relevance’ of this article is perhaps most apparent). A recommendation would be to hire ‘insiders’ who already use the terminology as this can communicate that the business in question is sincerely trying to be part of the culture. Incorrect terminology and irrelevant content were the two main dislikes cited by the interviewees. When these two factors are present, they will have an adverse impact on the number of views each marketing post receives. Many instructors are sponsored riders that already had a network set up for support promoting their sponsor. Since sponsorship is awarded at an early age, they have networks built up over the years. They also knew the most effective way of interacting with their target markets on social media. Interviewee B talked about being part of a brand Facebook group set up for marketing purposes:

“I have been part of hundreds of private groups, not hundreds maybe like 10 or 15, different ones over time that have been for specific brands to help their marketing to…give them the content and it is closed private groups where they can get the content and then put it wherever they want” (Interviewee B).

Anyone actively taking part in promotion activities from an early age quickly develops (sub)culturally-appropriate communication, networking, and promotion skills, making the person ideal for a marketing role within the industry.

When commenting on other platforms used by marketers in the industry, Interviewee B responded as follows:

“Well, they should use Instagram more and not just to advertise events or products but just for the sake of posting stuff that’s going on that is interesting; otherwise people do not follow you and that is the point. If you only post about your products constantly people get a bit saturated and bored of it, that is why I would say it is so important that marketers themselves have or at least someone on the marketing team should have a vested interest in snow sports. Having a YouTube where you take the mick half the time and the rest of the time you promote your product is perfect; or on Instagram you get a minute video; on Instagram it is perfect” (Interviewee B).

Most interviewees spoke about the need for ‘fun’ content along with promotional content to ensure followers view their content. Facebook became mainstream for this market, Instagram is very much where it is at for this market; however, if the user does not like or interact with any of the page posts, then the posts are increasingly less likely to appear on the user’s feed. Including fun content encourages interaction but also leads to the user visiting the page to watch the videos for enjoyment. In the current digital world, where people now only see what is in their ‘bubble’, the best way to get into that bubble and stay there is to create content which people return to see. Businesses should ask themselves how they can make their material stand out from the pack so that the target market comes to them. It is not difficult to make this sort of material within the snow sports industry; filming park runs, and tricks is already a commonplace and accepted thing in the culture, meaning there is a likelihood that employees and customers already have a trove of videos that can be used (with their permission) thus making the complete process more costeffective.

Tourism Motivations, Domestic and Abroad

When asked to compare skiing in Scotland and other countries, Interviewee D stated:

“Scotland is just as good for that one or two days of the season when you get perfect conditions and the weather’s good and it has snowed the night before. I think the downside to Scotland is the unpredictability of it. You can go up for a week and, in that week, you have one cracking day or two cracking days and then three days of slush and sleet and wind. I think probably it is the one thing that puts me off” (Interviewee D).

When discussing festivals, some interviewees identified people who were not into snow sports attending snow sports festivals for music and fun. It was important to note that they did not participate in snow sports; there is the potential to pull in a large number of ‘new’ people that can become a target market for the snow sports industry both domestically and internationally. Interviewees were asked whether they visited the mountains during the summer and what encouraged them to visit in the off-season. Most stated that they wish they got up more in the summer months because the mountains were beautiful in the summer; motivations included participation in other extreme sports and activities with the most popular being mountain biking. “Yeah, more mountain bike trails and also just more adventure like activities outdoors like even just simple parks built into the woods” (Interviewee H).

When asked what would encourage him to go on trips more often to the mountain during the off-season, Interviewee C stated:

“Something that really caught my fancy, but it would have to be something such as lessons on a sport I find interesting; you know, an activity and not just sightseeing. I think the best way to do it is if I went with a group…for the social side of things” (Interviewee C).

People who looked for thrills in the summer would likely be just as inclined to do a similarly or equally thrilling activity during the winter. Climbing lessons might be popular as many climbers do their climbing indoors but desire to take it further and climb real walls. Climbing lessons might attract a new market but also keep businesses afloat outside the winter season as people continue to find new and exciting thrills.

When asked whether and how summer tourism could be boosted, Interviewee B stated:

“Yes definitely. I heard that Glencoe is building a road from their mid station to the bottom and leave the lift open during the summer so people could longboard and stuff; I think ideas like that would definitely make it better and that is a brilliant idea; they already have a chairlift!” (Interviewee B).

The connection between snowboarding and skateboarding subcultures was often cited by the interviewees. Many snowboarders would switch to a skate or longboard during the summer as the activities are similar in form and culture. Skating on roads is a smart way to keep customers in the off-season. To summarize, although the main motivation for snow sports tourism depends heavily on weather, other influences including attending events, festivals, and competitions were discussed. Interviewees stated that fun activities were their biggest motivator when considering visiting the mountains during the winter; specific activities identified as being interesting and attractive were downhill mountain biking; climbing; and longboarding. Collectively, the results suggest that market research is required so that resorts can understand their target market(s) better.

Marketing

When asked whether marketing snowboarding to other subcultures (i.e. extreme sports) would lead to more people getting into snow sports, Interviewee A stated:

“If you advertise to other extreme sports yeah, [people]… will definitely give it a shot, and they probably already have it in mind to give it a shot, it just might give them that push but they are going to try it either way. You know like I have friends in the professional BMX committee; I have friends in the professional skate community; and both are the same, and like complete opposite sides you know of like speed climbing. I have friends in that, that want to try snowboarding, it is just because their speed climbing takes over. That is where they are getting that thrill from right now” (Interviewee A).

Although initially agreeing that it would be beneficial to advertise to this thrill-seeking market, Interviewee A made a compelling case for advertising outside of this market, as the people who are ‘hooked’ into the thrill market already have their preferred thrill and do not have the time to commit to another activity or hobby.

Interviewee C’s response differed from other interviewees on this point as follows:

“Yeah, I think there are certain sports [which can be marketed to by the snow sports industry]; skateboarding is a good example, as there are less [sic] barriers to get into it, as you do not need snow, you can do it all year round, and I think that the [skateboarding] customer base do their sport for a lot of the same reasons and drives, and I think that makes them an attractive market for the industry as they already have a good level of fitness that they can bring to the sport plus, if they are doing a lot of outdoor stuff already, then they are probably already quite self-motivated which I think is really important” (Interviewee C).

Interviewee C pointed out that individuals within the ‘thrill market’ are more likely to engage in snow sports and are expected to pass lessons quicker than someone outside of this market or demographic, which makes them a ‘desirable’ market. Realistically, marketing within the thrill market can be done by simply asking for a poster to be put up; for example, a poster offering discounted lessons at a climbing center would reach this market. Once these thrill-seekers are in, they become easy marketing targets. However, it should be noted that, just because something is easy, it does not mean that it is by far the preferred or best option. Marketing outside of the thrill market would encourage people into the market. If introduced to the market via snow sports, snow sports would become their first thrill which would hook them into snow sports. They might well then keep their focus on and loyalty towards snow sports because they are yet to find other thrills.

When asked whether he thought snowboarders and skiers fit into one easily marketable category, Interviewee C stated:

“Snowboarding has a lot of segments even down to the board they buy, whereas skiing is a lot more homogenous and the language you use would be different if directed at say a park rat; I would not use the same language if I was marketing to an allmountain boarder or a boarder-cross person because they have different needs and different wants with the exception of the common theme that everyone wants… snow!” (Interviewee C).

Interestingly, Interviewee C’s answer differs from other interviewees: he made a persuasive argument for separation of skiers and snowboarders into two separate categories for marketing purposes based on the implied argument that they are distinct but connected subcultures.

When asked whether separating snowboarders and skiers would be a more beneficial way to advertise, Interviewee A stated:

“Nowadays: no. Nowadays it should be seen as under the same roof. Skiers and snowboarders should be under snow sports. Separating helps spread discrimination and hate” (Interviewee A).

Most interviewees acknowledged the divide between skiers and snowboarders and agreed that they should be marketed to together. There was a clear desire to get away from past discriminations against snowboarders, although marketing brands to both skiers and snowboarders separately makes logical sense as usually equipment and clothing is purpose-made for a specific style. However, marketing of events should be aimed at skiers and snowboarders as a combined group. A poster for a freestyle night, for example, should include both a snowboarder and a skier on the poster, encouraging both sides to try different styles and to socialize at events which will help towards achieving the goal of getting away from past discriminations. To summarize, the interview results suggest that, although customers can be brought in from the ‘thrill market’, there can be more benefits to be found outside this demographic. Snowsports bring people into the market, and, if it is their first ‘thrill’ activity, they are less likely to have other passions and hobbies which take up their spare time. When marketing to skiers and snowboarders, consideration should be given to past discriminations and how the marketing material provided helps to eliminate discrimination and bring people together. When advertising events or festivals both skiers and snowboarders should be featured in advertising material so as to aid the elimination of discrimination in the industry. However, equipment and clothing advertising can be reasonably segregated due to different purposes and styles.

Employment, Job Opportunities, and Security

When asked to comment on the most critical issue facing snow sports in Scotland, Interviewee B stated:

“I think in terms of the whole U.K. what [we]… have got to worry about is filling in the gap between recreational skiers and getting them to a high standard; that kind of ties in with Scotland as well as we have the same problem. When speaking to foreign instructors they always say that the British guys, the BASI coaches, are brilliant at getting people from complete novice to recreational standard but let themselves down going from recreational standard to Olympic [standard]; there’s not really that high-end coaching so I think on a national/ U.K. level that’s one of [our] big problems” (Interviewee B).

A lack of opportunity for progression training in the U.K. (which includes Scotland) has led to U.K. instructors not meeting up to the standards of instructors in other countries, specifically when teaching people to refine their skills to reach Olympic standards. This problem limits employment opportunities for BASI instructors internationally and lowers the reputation of the qualification. The U.K. should do more to support career progression for instructors. The lack of skills also leads to a disadvantage when competing in the Olympics. Although there are skilled and qualified instructors in the U.K., the lower concentration of skills may impact on the number of young people pushing to compete, as instructors often spot and encourage new talent.

When asked what threatens job security in the snow sports industry in Scotland, Interviewee D stated:

“To be honest I am not really worried about it, it is more about making the hours up because I was never on a long permanent contract. It was just zero hours at one point which was good while I was going through university, but now and again I did go ‘hold on, what about the summer?’ I [hope that I] am going to get the hours when I am not in university” (Interviewee D).

Interviewee D’s reply showed that the style of working tends to suit students, although they are still worried about making up hours in the summer. This was more of concern for indoor and dry slopes that have permanent staffing throughout the year. To summarize, employment opportunities and job security can have a impact on the snow sports industry in that a lack of opportunity has led to a skills shortage in the U.K. and a lack of training available for talented young people. Some of these people could have competed in the Olympics or other competitions, which would have helped to create a more positive image of the industry in the U.K. Employers should do more to support employee progression, so as to ensure opportunities in other countries during the U.K. summer. Passion and enthusiasm are required of instructors during lessons to ensure the customer is engaging but also most importantly enjoying herself or himself. Low job security and lack of progression opportunities lead to lower job satisfaction, affecting the quality of the lessons given. It is recommended that businesses support progression and have regular contacts with staff to discuss the business position and keep them informed of the financial performance of the business.

Young People

When asked the most critical issue facing the whole snow sports industry in Scotland, Interviewee A stated:

“Unfortunately, people still think that skiing is better and more than what snowboarding has become, even though a Brit took a bronze [medal] for snow for the first time in the history of Britain and there still kind of like ‘ah yeah well uh … Yeah... snowboarding…yeah’ and that is it you know, they overlook it when there’s so much talent within Britain, Scotland, England, Wales, and [Northern] Ireland. It does not matter that there is so much talent on the snowboarding side, whether it be freestyle, boarder cross, half pipe did not matter there was so much talent, but it got over looked” (Interviewee A).

Interviewee A expressed his frustration at snowboarding not being identified as a ‘proper sport’ in the way that skiing is viewed. He stated that the history of discrimination toward snowboarding still exists when it comes to the Olympics, even though the first Brit to take a snow medal in the Olympics was a snowboarder.

“You know like I did get offered it years ago to get training for the G.B.; maybe ten years ago now but like the skiing. The athletes got their training paid for from the country; you know it was a part of the Olympic council or community. They had their trip paid for them but no for snowboarding, no, each athlete had to pay for themselves. I do not know what it is like now but back then they had to pay for themselves; and for a season for training and trips away it was like five grands [£5,000], and you are asking you know 16-year-olds just finishing high-school that [have] likely not got a job yet…” (Interviewee A).

Interviewee A talked about missing out on opportunities himself due to discrimination between skiers and snowboarders in the past. It is unlikely that no-one else experienced similar problems. It is easy to see how a family could struggle to commit that amount of money for a ‘chance’ at success. It is a massive risk which could end up completely backfiring, such as falling and causing injury which takes the rider out of the game. Had there been more support for snowboarders in the past, it is possible that Britain could have significantly increased its chances of winning a medal on snow before 2014. As shown in the ‘Jenny Jones effect’, snowboarding boomed after Jenny Jones won at the Olympics. The biggest winner was Mendip Snowsport Centre in Churchill, Somerset, England where Jenny learned to snowboard. Identifying a business with the success of an Olympian would attract business, especially from young people who have the desire to compete themselves. It was recommended that indoor and dry slopes encourage talent as success was good for both the customer and the business.

When making suggestions about getting more young people involved in snow sports, Interviewee A pointed out:

“Just put it across as an experience, they try and put it across… like ‘it would change your life or your future’, that does not work for kids, because you want to try and put it out there, so it relates to them. It is cool, they like cool so make it as flamboyant as you can. You know just to try and make it look cool to try and make it ‘aww! That looks amazing! I would love to do that!’…” (Interviewee A).

All interviewees talked about showing young people how ‘cool’ snow sports were through online media or in physical form. Most interviewees stated that they did not believe the issue is about young people wanting to participate, but barriers created (e.g. funding). To summarize, the results show the need to create opportunities for young people which can benefit both the young and the businesses. It is recommended that organizations within the industry do what they can to support and promote talent. The ability to associate an elite athlete with a business helps to motivate others to learn at that facility, as they associate the facility with high performance.

Conclusion

Thematic Analysis

This article aims to provide an insight into issues faced by the snow sports industry in Scotland based on data collected during the 2016-2017 winter season.

Theme 1 - Backgrounds and Influences

Backgrounds and influences are considered relevant to all replies as an individual forms thoughts and judgments based on her/his previous experiences. Backgrounds and influences of the interviewees can provide insights into some of the other issues identified. Considering young people, one of the issues looked at is how to encourage young people into snow sports. Therefore, finding out how the interviewees were introduced to snow sports could give insight into how to get more young people involved; that could be from a marketing point of view, finding out the best way to reach younger people, to understand the benefits for businesses and non-profits linking up to promote snow sports to young people. To summarize, the insights into what got the interviewees into snow sports help us to identify potential solutions to some of the issues identified, mostly the issue of encouraging young people into the sport. Marketing techniques that have been successful in the past can be identified and analyzed to find out if those techniques are still relevant, still in use and should be still in use; how older techniques compare with techniques used now will be explored further in Theme 5 - Marketing.

Theme 2 -Weather

Weather is an issue linked to most of the other themes (e.g. Theme 4 - Tourism motivations and Theme 6 - Employment, job opportunities, and security). Because the industry is heavily weather-dependent, unfavorable weather influences tourists’ motivations, which in turn leads to fewer customers at resorts leaving instructors with empty lessons and less chance of getting the working hours they need. Themes 4 and 6 explore some of these issues further. As snow sports are highly dependent on weather, unpredictable weather has led to issues in many parts of the industry. The results show that weather is a major issue for the industry. A lack of suitable conditions can affect resorts in the mountains. The effects can be severe, resulting in resort closure or affect tourist motivations when considering trips. Weather can also impact job security within the industry, resulting in low levels of staff satisfaction and customer experience. Although weather is out of the control of the industry, it is recommended that resorts push summer activities to spread the costs and ensure steady cash flow throughout the year. Resorts are recommended to build up reserves to deal with bad seasons.

Theme 3 - Subcultures

Theme 3 explored the idea of a subculture within snow sports. Many characteristics of a subculture can be identified in both freestyle snowboarders and skiers. When identifying a subculture within snow sports, snowboarding can easily be identified as a subculture just by looking at the history of snowboarding; however, it was interesting to identify that the subculture now is more about freestyle rather than just snowboarders. The analysis showed that language and terminology played a significant role in successfully marketing to this group. It has been suggested that recruitment in marketing should take interest into account (e.g. sponsored riders could become strong marketers within the industry). Interviewees have expressed the need for ‘fun’ content to keep the market’s attention. This is partly due to the current nature of social media where users only see content from pages and people with which they regularly interact.

Theme 4 - Tourism motivations

Tourism motivations are the reasons why people travel. With no surprise, the weather was cited by many of the interviewees as a key influence when considering a snow sports trip. This article explicitly stresses the need for resorts to pull in customers outside the winter season to ensure steady cashflow throughout the year and to create enough reserves to ensure the resorts can make it through any future bad seasons. Interviewees were asked about motivations during the summer months to identify activities that do and would encourage them to visit the mountains during the summer. Weather unpredictability in Scotland can be just as much of an issue in the summer for the mountain resorts as it is in the winter.

Theme 5 – Thrill Market

The idea of a ‘thrill market’ was raised by a few of the interviewees. Would it be beneficial to focus advertising for snow sports within or outside the ‘thrill market’? The assumption initially was that it would be more beneficial to advertise within this market, as you are advertising to people with interest in thrill activities. However, our interview findings suggest that it might be more beneficial to advertise outside of the ‘thrill market’. Interviewees were also asked about their opinions regarding marketing to skiers and snowboarders as two distinct markets or should they be marketed to as a combined group. Although most interviewees agree that marketing should be directed at a combined group, not all agree with this and some strongly believe they should be marketed to separately.

Theme 6 - Job Security

Most interviewees cite weather as the key worry regarding job security in the industry. This includes jobs in indoor slopes that are not physically affected by the weather. Job opportunities arise the more involved a rider gets in the subculture. Some of the interviewees spoke about job opportunities that they had taken which were sourced through someone in the subculture. Clearly, to use the term of Kahn-Harris [9, 10] and Thornton [13], those individuals with higher subcultural capital will receive more and better job offers than others. Interviewee D spoke about using instructing as a fallback job while he tried to find a way towards his desired career.

Theme 7 - Young People

The literature review suggests that there has been a decrease in young people getting involved in snow sports. When discussing young people, most of the interviewees agree that more community outreach and school participation is required to help bring more young people into the sport. One concern is that it is too expensive to get into if you do not come from a welloff background: this is where community outreach and school participation could be beneficial. Lack of opportunity for young people to progress within snow sports holds back the rider and the businesses. This can be shown when considering the ‘Jenny Jones effect’ at the Mendip Snowsport Centre - the facility Jenny Jones learned to snowboard. Each theme identified correlates with one of the other themes in that if there is an issue identified within one theme this issue will also affect one or more of the other themes. This was noticeable when considering Theme 3 (subcultures); Theme 5 (marketing); Theme 6 (employment); and Theme 7 (young people).

Policy Recommendations

An issue identified is the inability of resort and business marketing teams to reach a sizable proportion of their target market. It has been identified as an issue surrounding subcultures and their distaste for the mainstream world. Due to this, subcultures are notoriously difficult to market to and are often seen as ‘undesirables’. Someone with high subcultural capital Kahn-Harris [9, 10] and Thornton [13] within the subculture may have very low cultural capital outside of it and vice-versa. To make it more confusing to outsiders, Kahn-Harris [9] argues that subcultural capital is of two types - the mundane and the transgressive which might appear to be in contradiction to each other. These two types of subcultural capital were explained in our Theory Framework section. It is recommended that businesses conduct market research into subcultures to better understand each subcultural market. Subcultures become relevant for many themes, even having an influence on opportunities for young people due to a history of discrimination between skiers and snowboarders. Many resorts have made efforts to negate some of the issues identified in this article (e.g. weather). Some resorts provide other fun activities (e.g. downhill mountain biking) to keep customers visiting. It can be recommended that further market research into the ‘thrill market’ should be conducted to find out what percentage of advertising is aimed at this market currently. It is suggested that advertising outside of this market would be most beneficial as outsiders have yet to experience a thrill. Therefore, they are more likely to get hooked on snow sports.

Aside from filling up mountains with snow cannons, there really is not much else that can be done about the weather. However, the resorts do have control over equipment and other activities which can be provided as an alternative. What can be controlled are the opportunities for young people. The 2014 Olympic win for snowboarding created a boom within snowboarding, when Jenny Jones took the first ever medal for a snow event for Britain. The training facility where Jenny learned saw a significant boom, which shows the power of having an Olympic medal winner associated with a facility. It is recommended that training facilities (e.g. dry and indoor slopes) encourage and support young talents, increasing their chances of establishing an association when and if the rider is successful.

References

- Merritt M (2017a) No Snow, but no panic at Scottish ski centres, The Courier & Advertiser.

- Cramb A (2009) Scottish ski industry could disappear due to global warming, warns Met Office, The Telegraph.

- Highlands and Islands Enterprise / Scottish Enterprise (2011), Scottish Snowsports Strategic Review [online] (Glasgow: Tourism Resources Company).

- Cox R (2013) Beinn Ghlas: the birthplace of competitive Scottish skiing, The Guardian.

- The Independent (2017) Fifty years of skiing history, The Independent.

- com (2017) History of snowboarding / snowboard.

- De Burgh‐Woodman H, Brace‐Govan J (2007) We do not live to buy, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 27(5-6): 193-207.

- Kahn-Harris K (2004) The ‘failure’ of youth culture: Reflexivity, music and politics in the black metal scene, European Journal of Cultural Studies 7(1): 95-111.

- Kahn-Harris K (2007) Extreme Metal: Music and Culture on the Edge (London and New York, NY: Berg).

- Kahn-Harris K (2004) The ‘failure’ of youth culture: Reflexivity, music and politics in the black metal scene, European Journal of Cultural Studies 7(1): 95-111.

- Bourdieu P (1979) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (London: Routledge).

- Bourdieu P (1993) The Field of Cultural Production (Oxford: Polity Press).

- Thornton S (1995) Club Cultures: Music, Media and Sub-cultural Capital (Cambridge: Polity Press).

- Coggins O (2018) Mysticism, Ritual and Religion in Drone Metal (London and New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic).

- Baulch E (2003) Gesturing elsewhere? The identity politics of the Balinese death/thrash metal scene, Popular Music 22(2): 195-215.

- Baulch E (2007) Making Scenes: Reggae, Punk, and Death Metal in 1990s Bali (Durham, NC: Duke University Press).

- James K, Walsh R (forthcoming), Islamic Religion and Death Metal Music: Part 1, Journal of Popular Music Studies.

- Wallach J (2008) Modern Noise, Fluid Genres: Popular Music in Indonesia, 1997-2001 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press) 21(3): 396-377.

- Wallach J (2011) Unleashed in the east: Metal music, masculinity, and ‘Malayness’ in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, in J Wallach, HM Berger and PD Greene (Eds.), Metal Rules the Globe: Heavy Metal Music around the World (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press) 4: 86-105.

- Gössling S (2007) Tourism and Global Environmental Change, 1st (London: Routledge).

- Unbehaun W, Pröbstl U, Haider W (2008) Trends in winter sport tourism: challenges for the future, Tourism Review 63(1): 36-47.

- Merritt M (2017b) Poor snow hits ski centre jobs, The Courier and Advertiser (Fife edition).

- Merritt M (2017c) Ski sites feel the heat as too little snow falls, The Herald.

- Prebensen N, Lee Y (2013) Why visit an eco-friendly destination? Perspectives of four European nationalities, Journal of Vacation Marketing 19(2): 105-116.

- Crompton J (1979) Motivations for pleasure vacation, Annals of Tourism Research 6(4): 408-424.

- Chartered Institute of Marketers (CIM) (2015) A Brief Summary of Marketing and how it works, 1st [ebook] (Berkshire: Chartered Institute of Marketers).

- Holloway J (2009) Marketing for Tourism, 1st (edn) (Harlow, Essex: Prentice Hall).

- Robinson P, Heitmann S, Dieke P (2011) Research Themes for Tourism, 1st [ebook] (Oxfordshire: CAB International).

- James K, Walsh R (2015) Bandung Rocks, Cibinong Shakes: Economics and applied ethics within the Indonesian death-metal community, Musicology Australia 37(1): 27-46.