How the Gender of the Riders Affects in the Relationship with their Horses

Alba Barros Guerrero*

Department of Sports, Univerdidad de Vigo, Spain

Submission: March 19, 2018; Published: April 02, 2018

*Corresponding author: Alba Barros Guerrero, Department of Sports, Univerdidad de Vigo, Spain, Email: alba.barros.g@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Alba B G. How the Gender of the Riders Affects in the Relationship with their Horses. J Phy Fit Treatment & Sports. 2018; 2(4): 555595. DOI: 10.19080/JPFMTS.2018.02.555595

Abstract

In equestrian sports it is very important that the riders establish a relationship with their horses. For this relationship to be good and stable, the riders must master certain psychological variables. Since in equestrian sports men and women compete together, we have decided to study what gender differences exist in the establishment of such a relationship. Although no statistically significant differences were found. The results show that women establish a better relationship than men with their horses, but it must be added, that the vast majority of riders of the disciplines studied, establish positive relationships with their horses.

Keywords: Psychological; Equestrian sports; Psychological variables; Gender

Introduction

The binomial is defined as the set of two personalities that play a important role in sports, artistic life, etc. On the other hand Hinde [1] defined a "relationship" as the bond that emerges from a series of interactions, in which peers have certain expectations of response about the other individual based on past experiences. Some studies help to explain the human attraction for equines [2,3] and, although scientific interest in human-horse interactions is becoming increasingly popular [4], the data that are available in this area they are still very limited. In equestrian sports, riders form close relationships with horses and it has been said that, in order to work optimally, rider and horse have to operate "as one" [5,6].

It is highly probable that the way in which the owners or caretakers see their horses has an important influence on the way they handle them, as has been shown for other domestic animals [7]. So if an animal experiences negative or positive experiences with a certain person, it is likely to show specific reactions towards that person [8,9]. Following Wang [10], relationship factors such as compatibility, mutual respect, close communication and trust are important. The rider must therefore master these factors to create a good relationship with his horse, thus improving the performance of both, because as mentioned by Hausberger et al. [11] a performance above the average depends on the effective cooperation between the rider and the horse.

We must mention that equestrian sports are the only ones in which two living beings of different species compete together to achieve a common goal. In addition, it is the only Olympic sport in which men and women compete together, in all its modalities and categories. For this reason, the objective of this paper is to study what differences exist between men and women in the domain of certain psychological variables that influence the relationship between rider and horse.

Materials and Methods

The sample to which the first version of the questionnaire was applied is composed of 102 riders in the disciplines of show jumping, dressage, horseball and pony, 40.2% of the sample are men and the 59.8% are women. The ages of the athletes are included between 7 years and 10 years, with the average age of 21.84 years and a standard deviation of 10,93.

The instrument used was the Questionnaire of the Relationship between the Rider and the Horse, in its Spanish version "Cuestionario sobre la Relacion entre Jinete y Caballo (CRJC)" [12]. This instrument is composed of 30 items that evaluate psychological variables and that are distributed in four factors: communication and empathy (8 items), bond (8 items), care and training (7 items) and emotional management (7 items).

The answers to these questions are graded on a scale of type Likert of 6 points, and ranging from 1: completely disagree ("It never happens to me"); up to 6: completely agree ("It always happens to me"). The completion time is approximately 30 minutes. Can be administered individually or collectively. The reliability of the questionnaire is high, with a Crombach alpha value of 0.81, form that is an appropriate instrument for the evaluation of psychological variables involved in the relationship of equestrian athletes with their horses.

Procedure

The data collection procedure for this study is carried out in two different ways, depending on whether it is applied in a club or if it is applied in a competition.

In the case of the clubs, the coach or director is contacted via telephone, agreeing on a date in which the application of the questionnaire will be carried out. Athletes are informed about the objective of the study, the mechanism of answer of the instrument, as well as the anonymity of the data obtained. In the case of the competition, we have addressed directly to the riders while they were observing the competition, avoiding to interview them in moments prior to the competition to not interfere with their concentration. These athletes were also informed about the objective of the study, the answer mechanism and the anonymity of the data After collection, data was analyzed through SPSS 21.0 software for Mac.

Results

Results Factor 1: Communication and Empathy

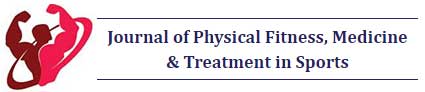

This factor evaluates how the riders communicate with their horses, both in the care and during the training, and if they empathize with them. To create a good relationship, the rider must know how to communicate properly with the horse, but also to interpret his body language. In this factor there are no statiscally significant differences in the scores between men and women (F = 1.86, p> 0.05), however, Table 1 shows the results in which women obtain higher scores than men.

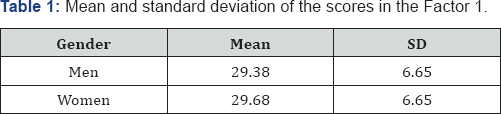

Factor 2: Bond

In team sports it is important that there is a bond or cohesion between the teammates to compete synchronized. This factor evaluates how is the bond between the rider and the horse. Statistically significant (F=4.82, p<0.05) we observed that women score higher on this factor (Table 2).

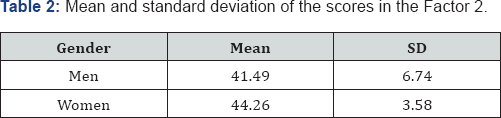

Factor 3: Care and Training

This factor assesses the responsibility and involvement of the rider in the care and training of the horse. It is common for the rider to be the one who trains the horse. On the other hand, as far as care is concerned, it is usually the case that on many occasions the stable boys spend more time with the horses than the riders themselves, since the stable boys are mainly responsible for all their care. So if the riders are involved and are motivated in these tasks, the binomial will be stronger. We can observe in Table 3, although without statistically significant differences (F = 0.06; p> 0.05), that women are more involved in the care and training of their horses than men.

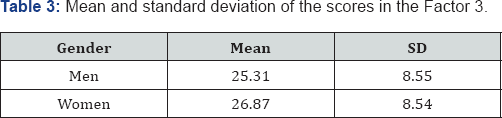

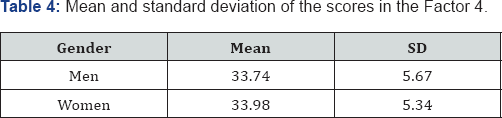

Factor 4: Emotional Management

This factor evaluates the the riders' abilities to recognize and manage their own emotions, as they will have a positive or negative impact on their relationship with the horse. Anew, although without significant differences, (F = 0.43; p> 0.05) are women who get a higher score (Table 4).

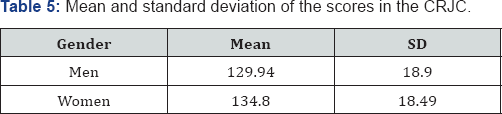

Total Score in the CRJC

We have established a cut-off at 90 points. There will be a tendency for a negative relationship with the horse when the riders score less than 90 points, while there will be a positive trend when the total score in the CRJC surpass 90 points. From a sample of 102 riders, there is only 1 case in which the score is lower than 90. Even though women score higher these results show that the vast majority of riders establish positive relationships with their horses (Table 5).

Discussion

In the revised literature, research was found on how psychological factors affect sport, taking into consideration the gender variable such as the study of Reche [13], but we have not found a study about equestrian sports.

The results obtained in Factor 1 agree with the results of other studies that show us that women communicate better with their horses and empathize more than men. Hall [14] argued that women observe others more frequently than men, which allows them to collect more non-verbal information and have apparent advantages in decoding the information of the facial expressions of others. Similarly, the review by Ickes [15] noted that in empathetic accuracy exercises that tested nonverbal sensitivity, women outperformed men in the experiments that made them conscious and more motivated for good execution.

Regarding the bond (Factor 2), the differences were statistically significant, resembling our results to those found in the study by Gonzalez-Ponze [16], in which the female soccer teams obtained greater social cohesion in front of the masculine teams. Previously, Reis [17] had already shown higher scores of women in interpersonal relationships with teammates than men. With regard to care and training, women also score higher in our study. Jones [18], found in his study that girls cared more about their horses than boys. Birke [19] also state that young girls tend to spend more time looking after horses.

In terms of emotional management and according to the scientific literature, women show a greater ability to perceive facial expressions of emotion than men [20-22], and in addition, they use more coping strategies focused on emotion than men [23]. In the study by Serrato [24], men are less sensitive to the adverse circumstances of competition, with women showing higher scores in emotional sensitivity. To find out that women have a greater ability to perceive emotions can, to some extent, be made to understand the existence of other gender differences, such as greater empathy on the part of women, greater expressiveness, more practice, greater tendency to adapt to others or a greater extent to use emotional information [25,26].

Finally, with regard to the total scores, and according to previous studies, in which women obtained a better command of psychological skills [13], in our study women have higher scores than men, which means that they have greater mastery in the psychological variables evaluated, obtaining a better relationship with their horse.

Conclusion

The main objective of this study was to find out what differences exist between men and women in the domain of certain psychological variables that are involved in the relationship between the rider and their horse. Although no statistically significant differences were found in the total score of the questionnaire, the results show that women obtain higher scores than men, as well as in the four factors, finding statistically significant differences in Factor 2. However, results show that the vast majority of riders of the disciplines studied, establish positive relationships with their horses.

References

- Hinde R (1979) Towards Understanding Relationships. Academic Press, Lodon, UK.

- Budiansky S (1997) The nature of horses: Exploring equine evolution, intelligence, and behavior. The Free Press, New York, USA.

- Grandin T (2005) Animals in translation: Using the mysteries of autism to decode animal behavior. Scribner, New York, USA.

- Robinson IH (1999) The human horse relationship: How much do we know? Equine Veterinary Journal 28: 42-45.

- Brandt K (2004) A language of their own: An interactionist approach to rider-horse communication. Society & Animals 12(4): 299-316.

- Meyers M, Bourgeois A, Le Unes A, Murray N (1999) Mood and psychological skills of elite and sub-elite equestrian athletes. Journal of Sport Behavoir 22(3): 399-409.

- Lensink J, Fernandez X, Cossi G, Florand L, Veissier I (2001) The influence of farmers' behaviour on calves reactions to transport and quality of veal meat. Journal of Animal Science 79(3): 642-652.

- Henry S, Richard Yris MA, Hausberger M (2006) Influence of various early human-foal interferences on subsequent human-foal relationship. Developmental Psychobiology 48(8): 712-718.

- Tanida H, Nagano Y (1996) The ability of miniature pigs to distinguish between people based on previous handling. In 30th International Congress of the International Society for Applied Ethology.

- Wang M (1988) The human and the horse. A pedagogic study of the horse as a teacher and as means of therapy. The Norwegian Postgraduate College of Special Education, Oslo, Noruega, Europe.

- Hausberger M, Roche H, Henry S, Visser EK (2008) A review of the human-horse relationship. Applied Animal behaviour Science 114(4): 521-533.

- Barros Guerrero A, Dosil J (2016) Construccion del cuestionario sobre la relacion entre el jinete y el caballo. Cuadernos de Psicologi'a del Deporte 16(2): 21-28.

- Reche C, Rojas F, Cepero M (2012) Perfil psicologico en esgrimistas de alto rendimiento. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte 7(19): 35-44.

- Hall JA (1984) Nonverbal sex differences: Communication accuracy and expressive style. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

- Ickes W, Gesn PR, Graham T (2000) Gender differences in emphatic accuracy: Differential ability or differential motivation? Personal Relationships 7(1): 95-109.

- Gonzalez Ponce I, Leo FM, Sanchez Oliva D, Amado D, Garci'a Calvo T (2013) Analisis de los procesos grupales en funcion del genero en un contexto deportivo semiprofesional. Cuadernos de Psicologi'a del Deporte 13(2): 45-52

- Reis H, Jelsma B (1980) A social psychology of sex differences in sport. In WF Straub (Eds.), Sport psychology Ithaca, Movement Publications, New York, USA, pp. 276-286.

- Jones B (1983) Just crazy about horses: the fact behind the fiction. In AH Katcher, AM Beck (Eds.), New Perspectives on Our Lives with Companion Animals, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, USA, pp. 87-110.

- Birke L, Brandt K (2009) Mutual corporeality: Gender and human/ horse relationships. Women's Studies International Forum 32(3): 189197.

- Babchuk WA, Hames RB, Thompson RA (1985) Sex differences in the recognition of infant facial expressions of emotion: The primary caretaker hypothesis. Ethology and Sociobiology 6(2): 89-101.

- Kirouac G, Dore FY (1985) Accuracy of the judgment of facial expression of emotions as afunction of sex and level of education. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 9(1): 3-7.

- Rotter NG, Rotter GS (1988) Sex differences in the encoding and decoding of negative facial emotion. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 12(2): 139-148.

- Yoo J (2001) Coping profile of Korean competitive athletes. International Journal of Sport Psychology 32(3): 290-303.

- Serrato LH (2006) Revision and estandarizacion de la prueba elaborada para evaluar rasgos psicologicos en deportistas (PAR-P1) en un grupo de deportistas de rendimiento en Colombia. Cuadernos de Psicologi'a del Deporte 6(2): 67-84.

- Hall JA (1979) Gender, gender roles, and nonverbal communication skills. In R Rosenthal (Eds.), Skill in nonverbal communication, Gunn & Hain, Cambridge, USA, p. 31-67.

- Noller P (1986) Sex differences in nonverbal communication: Advantage lost or supremacy regained? Australian Journal of Psychology 38(1): 23-32.