Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in Scottish Football: A Marxist Analysis

Kieran James*, Mark Murdoch and Xin Guo

School of Business and Enterprise, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley campus, Scotland

Submission: January 27, 2018; Published: February 08, 2018

*Corresponding author: Kieran James, School of Business and Enterprise, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley campus, Scotland, Tel: +44 (0)141 848 3350; Email: kieran.James@uws.ac.uk

How to cite this article: Kieran James, Mark Murdoch, Xin Guo. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in Scottish Football: A Marxist Analysis. J Phy Fit Treatment & Sports. 2018; 2(1): 555569 DOI: 10.19080/JPFMTS.2018.02.555569

Abstract

This article aims to examine and reflect upon the reporting of CSR activities undertaken by the 12 football clubs competing in the Scottish Premiership 2016-17 season. CSR strategies reflect the clubs' unique historical and geographical contexts. For example, Ross County serves a small population base spread over a huge rural district, which makes its situation very different from Aberdeen and Celtic. Aberdeen FC, with the appointment of a specific director in 2013, shows a clear level of stakeholder engagement. The delays to the new stadium, due to a cautious council and a residents' protest group, have frustrated the club's efforts and led to supporter discontent. Rangers' CSR activity including support for military veterans and education programmes for school-children reflects the traditional self-conscious Britishness and Protestant conservatism of the club as well as the club's desire to rebuild slowly and quietly after its 2012 liquidation and subsequent forced exile to the lower divisions.

Keywords: Alienation; CSR; Deprived areas; Football industry; Marxism; Poverty; Scotland; Scottish football

Abbreviations: SFA: Scottish Football Association; SPFL: Scottish Professional Football League; SIMD: Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation; EPL: English Premier League; NSL: National Soccer League; FFA: Football Federation of Australia; NKS: No Kingsford Stadium; HELP: Health, Equality, Learning and Poverty; AFCCT: Aberdeen FC Charitable Trust

Introduction

The primary objective of a professional football club is to achieve success on the field [1], but most clubs also claim to recognize that they have obligations towards their fans and their local communities. While the focus on CSR has become more intense in the last few decades, the relationships between for- profit institutions and the broader society have been a matter of interest for over 150 years. This is evident particularly in Scotland, with the country's historical, cultural, and social foundations. When Welshman Robert Owen bought cotton mills in New Lanark, his philosophy for socialism and experiments in improving his workers' conditions were successful and resulted in increased profits for his business. The Cadbury brothers, and, more locally in Scotland, Andrew Carnegie, are also high-profile examples of organizational activities coalescing with social activities. Many socialist entrepreneurs in Scotland have focused on the distribution of parts of their organization's surplus- value to society and improving the lives of people in their local communities [2].

Speaking of English football, Cloake [3] states that football clubs are unique in that they "lie in the efforts of church and factory to create community." Many men living in largely populated areas looked at football as a better outlet for their energies rather than drinking and fighting with one another. He explains that football relied on its surrounding industries for its own development, referring to steel, railways, and manufacturing industries; and the success of early teams in areas such as Derby, Manchester, Sheffield, and Stoke. A key topic of debate relating to sport, and specifically football, is its connection to the strengthening and maintenance of local communities. This is especially the case in Scotland where every small town has a club in the Football League or, below that, the Highland or Lowland Leagues or lower-tier or junior football. Hamil and Morrow [2] point out that it has been rare for Scottish clubs to relocate to more industry-based areas for commercial reasons but in turn this fact has allowed them to gain legitimacy from their historical ties to their communities.

Although most successes for professional clubs are measured by league table positions, cup trophy wins, and financial standing, their social and community responsibilities are often portrayed as being more important today than ever before. In 2010, a report commissioned by Supporters Direct [4] put forward the proposition that football clubs could have a significant impact in their local communities. Titled The Social and Community Value of Football, the report insisted that the value created by clubs' community arms should be measurable and comparable to similar clubs and it identified innovative projects and practices for the future. A key idea in launching CSR initiatives is to allow for business grant funding which can be explicitly attached to attaining a substantial level of community engagement. We are certainly not claiming that self-interestedness is not a motivating factor behind clubs' CSR work. As Karl Marx wrote, back in the Victorian era (when many of the leading Scottish clubs were formed): "The driving motive and determining purpose of capitalist production is the self-valorisation of capital to the greatest possible extent, i.e. the greatest possible production of surplus-value, hence the greatest possible exploitation of labour-power by the capitalist" [5]. The Scottish Premiership and the biggest Championship (second-tier) clubs all operate on a fully capitalist basis with the capitalist mentality or spirit being predominant. They see CSR activity and disclosure in terms of helping the clubs achieve their self-interested strategic agendas.

Although journals such as Soccer & Society and various edited book collections explore in detail the sociological aspects of football (i.e. soccer) and football fandom there have been fewer articles on football from an accounting / accountability perspective published in accounting journals. Some exceptions to this statement would be published articles by Christine Cooper [6-8] and Kieran James [9].

According to Grant et al. [10], sporting clubs and their fan-bases are excellent examples of post-modern community. Professional clubs celebrate historical moments or great performances and also celebrate their fans with social interactions and special rituals and traditions. For this reason, clubs are almost brand communities of which fans may feel a part (or in some cases and situations feel alienated from especially at English Premier League level). Football fans in a sense do have this right as they are certainly co-producers of the club's "brand". Old-school football fandom had its moment in the sun recently when 47-year-old Millwall fan Roy Larner acknowledged his club with "F*** you, I’m Millwall" in the midst of the London Bridge 2017 terrorist attack. He was widely praised for taking on knife-wielding terrorists with his bare fists (ibid.). Larner's case was highlighted shortly after by the Millwall Football Club in its online Face book marketing efforts; and Larner was paraded on the field before Millwall's first 2017-18 home game. Millwall is often presented, due to its working-class south-east London location and hooligan supporter tradition, as being an outcast in the face of the relentless power and logic of modern capitalist football. The club, through its contemporary online marketing efforts, walks a fine line in trying to not deny the romance associated with its outsider status but, at the same time, toeing the politically correct line needed now so that sponsors are not unnerved nor regulators displeased. With the club being promoted to the English Championship this season these tensions and contradictions will play themselves out on a higher and more visible stage.

The aim of this article is to examine the CSR reporting undertaken by 2016-17 Scottish Premiership (top-tier) football clubs over the three-year period 2012-15. The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 provides background information about Scottish football; Section 3 presents the Theoretical Framework; there is a Literature Review in Section 4; Research Method is presented in Section 5; Section 6 presents results; and Section 7 provides a discussion and conclusion.

Background

In Scotland, football has the highest profile of any sport and the SFA (Scottish Football Association) and the SPFL (Scottish Professional Football League) support 42 senior clubs across four divisions (Premiership, Championship, League One, and League Two). In Scotland most clubs are over a hundred years old (e.g. Greenock Morton was formed in 1874 and St Mirren in 1877) and have long been ingrained in and representative of their communities. Most of the clubs are professional and full-time across the top two tiers. However, several current and former Championship clubs are smaller and operate as part-time clubs with part-time players (e.g. Brechin City and Dumbarton and former Championship clubs Alloa and Ayr United (both now in League One) [11-13]. Twelve (12) clubs participate in the top-tier, the Premiership, with relegation and promotion at the end of each season to and from the Championship. There is also promotion and relegation to and from each of the top four tiers. Furthermore, the winner of the play-off games between the top Highland League club and top Lowland League club plays against the last-place team in League Two for a League Two spot in the following season. Most of the clubs are structured as limited liability companies [7]. The three biggest clubs, Aberdeen, Celtic, and Rangers, are run as public limited companies.

Scottish football is well known for the diversity in club size wixth two huge clubs (Celtic and Rangers); three medium-sized clubs (Aberdeen, Hearts, and Hibernian); and a host of smaller clubs often based in various satellite towns of Glasgow (Hamilton, Motherwell, and St Mirren) or in small regional towns. League one and League Two clubs had an average attendance in the 2015-16 seasons of 975 and 555 respectively. Hamil, Morrow [2] explains that, during the years 2006-11, several clubs saw substantial losses and many clubs filed for administration (but few actually went out of business). A look at Scottish clubs' annual reports for financial years 2012-13, 2013-14, and 201415 makes clear the financial strength of both Aberdeen and Celtic. They had a combined profit of £22.3m over these three years. Rangers' results provide another picture with the club set on rebuilding quickly to compete again in the top-quarter of the Premiership.

A key question raised in several articles relating to CSR in sport is how the thing that makes football so commercially valuable can be prevented from being destroyed, i.e. the passion generated by sport is threatened by its commodification. This aspect of our discussion is facilitated by our use of a Marxist theoretical framework. Table 1 shows the clubs’ stadiums' geographic locations and the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) (2016) numbers for those districts. A key to understanding the table is that, with ranking between 1-10, lower numbers represent most deprived areas (1, 2, 3 etc.) and higher numbers represent the least deprived. From the table, it is obvious that most of the clubs are based in some of the most seriously deprived areas of Scotland. Only Motherwell and St Johnstone’s locations scored 5 or above for overall SIMD ranking. This is interesting in that such profitable companies are based in deprived areas, in which they are so closely connected.

Theoretical Framework-Commodification and Alienation

Over the past two decades, football at the highest level around the world has changed dramatically in terms of finance. The “big bucks" media deals from BT and Sky have left clubs in smaller countries, such as Holland, Portugal, Romania, and Scotland, behind clubs they previously competed with effectively in European competitions, typically hailing from the “big five" leagues in Europe (England, Spain, Germany, Italy, and France [6] . An example of a club struggling in the new global reality is Steaua Bucharest (Romania) which won European tournaments in the eighties (UEFA Champions’ League / European Cup 1985-86 and runners-up 1988-89; UEFA Super Cup / European Super Cup 1986) but is now ranked club number 60 in UEFA (European confederation). Iconic traditional clubs from poorer countries, such as Olympiakos of Greece and Russia’s PFC CSKA Moscow, languish presently at the bottom or second-bottom of their Champions’ League group tables. Effectively these clubs and their fans, from poorer nations, are alienated, in the Marxist sense, from higher honours and prize-money (and the satisfaction which comes from these) as compared to the more financially strong clubs from the more lucrative leagues.

According to the young Karl Marx of the 1844 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, the capitalist mode of production (when compared to feudalism) alienates the worker from (a) the products produced; (b) the act of producing; (c) her / his species-being or true nature; and (d) other workers [14-19]. It is correct and acceptable theoretically to extend Marx’s theory to the alienation experienced by these clubs and their fans because the separation is a consequence of European football, at the top level, moving to higher and higher stages of capitalism (to use a term of Lenin) which excludes many from being able to effectively compete. The new football pitch is the boardroom and the bankers’ offices [6]; and games are determined before the teams walk on to the actual football fields (and we are not referring here to match-fixing as conventionally defined).

The explosion of the Asian market, with its insatiable interest only in the very top clubs and leagues, has helped the game attain a higher level of capitalism (to use Lenin’s term again) but alienated people in the process. For example, there is a popular television programme in Singapore which discusses English Premier League (EPL) games in depth but completely ignores the sport even at Championship level, which is silly from the pure footballing viewpoint as the top of the Championship and the bottom of the Premiership are not too different in most respects (in Scotland as well as in England). Furthermore, the promotion race in the Championship determines the next year’s EPL composition. This is an example of the process of commodification within late-stage capitalism in the globalized football industry where supporters are repositioned ideologically as consumers. Supporters from around the world care or pretend to care about famous clubs based in cities they have never been to and probably never will go to. Back in Europe, the grounds are designed with individual consumption of product in mind rather than the expression of community. High ticket prices (to be discussed shortly) and the concept of season tickets mean that stadiums at big clubs may be effectively sold out to middle-class consumers 10 months in advance. All-seater stadiums (mandatory in the top four tiers of English football as a result of the Hillsborough tragedy of April 1989) mean that you cannot sit near friends who buy tickets separately from you and the community atmosphere is less obvious than in the old days of concrete terracing. When Sheffield United's Blades hooligan firm members started watching games at pubs in 1997 in protest against rising ticket prices Armstrong [20] even describes this as "post-fan" behaviour.

In his discussion of commodity-fetishism in Chapter 1 of Volume 1 of Capital, Marx [21] gives the example of the carpenter's table (as commodity) taking on mystical qualities and rising up to haunt its creator, standing up on its own hind legs as "Capital". The theory of commodity fetishism is a direct extension of the young Marx's theory of alienation in the 1844 Manuscripts where the worker is alienated from the product produced, which stands up in opposition to her / him to oppose her / him [18].

The young Marx describes the hostile form of the commodity which stands up to oppose the alienated worker as follows: "... the more the worker exerts himself in his work, the more powerful the alien, objective world becomes which he brings into being over against himself, the poorer he and his inner world become, and the less they belong to him. It is the same in religion. The more a man puts into God, the less they belong to him. The worker places his life in the object; but now it no longer belongs to him, but to the object. The greater his activity, therefore, the fewer objects the worker possesses. What the product of his labour is, he is not. Therefore, the greater this product, the less is he himself. The externalization [alienation] of the worker in his product means not only that his labour becomes an object, an external existence, but that it exists outside him, independently of him and alien to him, and begins to confront him as an autonomous power; that the life which he has bestowed on the object confronts him as hostile and alien" [22].

Marx [23] defines capital as money "invested in order to produce a profit". Therefore, it is capital (rather than money or individual businesspeople) which is the contradiction of living labour and it is capital which stands up in opposition to the worker to oppose her / him. If money is not invested in order to make a profit (e.g. in the feudal mode of production), then we have only use-values and the carpenter's table is not able to haunt its creator; it remains simply a table. However, once it is produced by a capitalist and sold on the market, the table takes on mystical qualities and enters into mystical relations not only with its creator but also with other tables. In Marx’s [21] words: "A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.

So far as it is a use-value, there is nothing mysterious about it, whether we consider it from the point of view that by its properties it satisfies human needs, or that it first takes on these properties as the product of human labour. It is absolutely clear that, by his activity, man changes the forms of the materials of nature in such a way as to make them useful to him. The form of wood, for instance, is altered if a table is made out of it. Nevertheless the table continues to be wood, an ordinary, sensuous thing. But as soon as it emerges as a commodity, it changes into a thing which transcends sensuousness. It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than if it were to begin dancing of its own free will"

In Marx [22], the commodity stands up and dances in front of only the worker whereas in Marx [21] the commodity stands up and dances in front of other commodities as well as consumers. A commodity recognizes something of itself in all other commodities. Commodity A knows that it is a commodity only because Commodity B (to which it is related through the exchange relation) serves as a mirror in which its own true nature can be observed. Hence, we have tables dancing together in apparent relationship and intimate association. To explain this, Marx notes that Peter can know his true nature as a man after he observes another man, Paul, in whom his own nature is reflected.

Commodity production under capitalism is described as "magic and necromancy" since it obscures a social relation among human beings. This is what the "magic" of the EPL has become rather than any other type of magic. What appears as a material relation between things hides the social relation between human beings that comes into being at the moment of commodity exchange. The commodities are injected with life. Marx [21] writes that: "Despite its buttoned-up appearance, the linen [Commodity A] recognizes in it [the coat, i.e., Commodity B] a splendid kindred soul, the soul of value". Each commodity is a "citizen of that world", i.e., "the whole world of commodities" As Trotsky [24] makes clear, a true Marxist critique must aim to reveal the social relations hidden and obscured by market (economic) relations. Only a "Marxist criticism ... calls things by their real names". Therefore, it is a "part of our liberation" [25].

The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) (2016) shows that 13 professional clubs are located in the most deprived areas of Scotland, including Glasgow and Dundee. However, despite this, Glasgow-based Celtic, a club founded with a Roman Catholic charity ethos to help unemployed and poor Irish immigrants, has been recently charging around £15 for a child's ticket at Celtic Park. Further to this, Gannon [26] states that children (under-13) season-ticket holders at Celtic Park are being asked to pay £81 for the three home Champions' League games of the 2017-18 season (£27 per game) or forfeit their seats to adults paying the one-off price of £50 per game. (The adult season-ticket holders are being charged £114 for the same three-game package.) The St Mirren club, playing in Scotland’s Championship (second-tier) and based adjacent to Ferguslie Park, Paisley (Scotland’s most deprived area), charges as much as £20 for an adult's ticket while 13-year-olds and above have to pay the adult price.

Many Scottish fans are disillusioned and feel that they are not getting value for money. They rejoice in reading about exManchester United and England champion Wayne Rooney's afterhours exploits involving country pubs, women, and breathalyser tests in the Daily Mail because they cannot reach him in any other way as he lives behind mansion walls and tight security. By contrast, former Fiji national team players such as Henry Dyer and former national league coaches such as Roblin freely talk to fans in pubs and at grounds in Fiji where players have never had much remuneration beyond free alcohol and FJD50 a game (source: third-mentioned author’s conversations with Henry Dyer, Nadi, Fiji Islands, 2014-17; the same author's conversations with current Lautoka national-league players at South Seas Club, Lautoka, Fiji Islands, 2015). These high ticket prices have raised the question in communities as to whether the bigger football clubs in Scotland show any social responsibility towards them when they are run like other commercial businesses.

Literature Review

Cooper, Johnston [6] uses Bourdieu and Lacan’s theories to analyse the takeover of Manchester United Football Club (EPL) by the American Glazer family in 2005. They also discuss the Vulgatization of the term “accountability" in modern times (say, post-1989) where it hides more than it reveals because the thought behind it is incomplete (p. 611). In fact a word becomes "vulgate", for Cooper and Johnston [6], when “it appears to be progressive but in practice has taken on multiple meanings such that it lacks political force". Accountability can refer to either a psychoanalytic concept or the concept used in business circles today where accountability of a division or government department is expressed in terms of ability to control and then punish those who cannot generate a high enough rate of return (or meet other KPIs). Use of performance measures (neo-liberal KPIs) in this way creates delusions of power and grandeur on the one hand and stress and anxiety on the other (p. 603) as well as undesired outcomes relative to corporate strategy. Despite the accountability rhetoric, citizens in the present era have no actual power to remove (for example) the heads of privatized utilities (p. 605).

The authors demonstrate that, despite endless talk of accountability plus the publication of annual financial statements and adherence by the Glazers to laws and listing rules, the final outcome was only an appearance of accountability since the fans had no power at all to block the takeover (pp. 622-3). The Lacanian insight is that individuals suffer anxiety because they require and desire the recognition and approval of others as part of the self-understanding and self-evaluation process. This leads to efforts to appease others (and / or to condemn and belittle others so as to retain a self-image of perfection) although the need to appease may not extend to those with lower symbolic reputational capital (pp. 608-9). As the authors write: “The interesting question here is whether or not all actors ... depend on recognition from all others regardless of whether this is the recognition from a person of superior or inferior status" Therefore, as the authors convincingly conclude, the Glazers were not much concerned about the hostile and negative opinions of ordinary fans. Indeed they were much more interested in the approval of bankers and financial community heavyweights since that was the community which they had chosen to inhabit and to identify with.

Cooper and Joyce [7] (later updated as Cooper and Joyce [8]) use the concept of “private ordering" and aspects of Bourdieu's work to analyse as a case study the administration and insolvency of Gretna FC shortly after its surprise promotion to the Scottish Premiership (as it is now called) in 2007-08. The final liquidation of the club occurred on 8 August 2008 after the conclusion of the Premiership season. “Private ordering" refers to the situation where a private body fills the gap perhaps once filled by government and sets rules which impact upon individuals who have no input into the rule-making process. A contemporary British example would be private car-park operators with the various fees and fines which they charge. Cooper and Joyce [7] argue that the Scottish Premier League Limited (hereafter SPL), a private limited company, practiced private ordering and enforced this on Gretna FC (and its supporters) which had no ability, whilst under administration, to contest the policies and decisions of either the SPL or the insolvency specialist.

The super-creditor rule existing in England means that “football debt" (payments owed to “football people" such as other football clubs and the regulatory bodies as well as players and managers) are paid before non-football debt (including payments owed to cleaners, shop staff, and stewards). This English rule, supported by the English court decision in Inland Revenue Commissioners vs. The Wimbledon Football Club Ltd, imposes marginalization and discrimination upon the nonfootball staff that are in many cases amongst the poorest paid people at a football club. In Scotland, “football debt" is defined as: “unpaid ticket revenue, unpaid transfer revenue and unpaid elements of player contracts" [8]. However, the super-creditor rule is selectively enforced in Scotland, unlike in England, and it is not part of the official rules of any Scottish regulatory body. In the Motherwell and Gretna insolvencies, footballers were lumped in among regular creditors and received no special treatment. By contrast, amounts owed to other football clubs were paid first. This state of affairs rests uneasily with the cited statement by the SPL’s (Operations Director / Company Secretary) Iain Blair in the article (p. 124) that clubs break SPL rules if an administrator breaches player contracts such as cutting wages or making players redundant (as happened at Gretna). Cooper and Joyce [8] conclude that: “the SPL allowed Motherwell to breach its [SPL’s] own albeit unwritten rules".

The losers of the Gretna FC saga are all those who bemoan the disappearance of Gretna FC, many of whom did not necessarily want the club playing in the Premiership in the first place. The insolvency firm allegedly charged £253,000 in the first five weeks of administration and, aided by the fact that the club went into administration rather than liquidation, unsecured creditors stood to receive less at the end of the process (after fees paid to the insolvency specialist). On 26 March 2008, 28 staff members (including 22 players) were made redundant. The club's land at Raydale Park was sold for £300,251.

In April 2008 the administrators published a list of 139 creditors owed £3,734,812. Football debt (owing to clubs) was £81,488. The total fee paid to the insolvency specialist was £482,851 but only £715.65 was ultimately available to pay unsecured creditors, including players. The SPL did not require that the insolvency specialist treat amounts owed to redundant players as priority creditors. Unsecured creditors' total loss was almost £4 million while the state (HMRC) lost £576,055. The 10-point deduction due to entering insolvency, a SPL policy, made relegation of the club at the end of the season more probable and so contributed to the club's demise. The SPL, as a private limited company, maintained its symbolic reputational capital by funding Gretna FC on a temporary basis so that it could play out its final games until the end of the season. Meanwhile, other low-placed Premiership teams rejoiced at the 10-point deduction because it assisted them to retain their Premiership spots.

Fortunately, time has shown that new club Gretna 2008 has stabilized its position in the Lowland League (ninth place out of 16 in 2016-17) and the new club has secured permission to play at Gretna FC's Raydale Park. There were legal ownership issues arising out of the original transfer of this stadium to Gretna FC but the supporters' group did not have the £50,000 needed to challenge this in court during the insolvency process. This was a further barrier facing supporters who might have hoped to be able to impact this process which was run and controlled by the insolvency specialist (who had the necessary cultural, economic, social, and symbolic capital). These authors explore a similar theme as in Cooper and Johnston [6] (although this may not be immediately obvious) and reach an identical conclusion as in Cooper and Johnston [6]. In both articles accountability is allegedly present, and rules are adhered to, but the disenfranchised are powerless to influence decisions which affect them. Private ordering is now widely perceived as being legitimate although it lacks many of the traditional procedural safeguards of governmental law-making.

James et al. [9] studied the cancellation of Australia's National Soccer League (NSL) and its replacement with the corporatist A-League in 2004-05. They point out that the NSL was mostly made up of traditional clubs based around one particular European ethnic community (e.g. Melbourne Croatia, Preston Makedonia, South Melbourne Hellas, Sydney Croatia). No member of the NSL was guaranteed an A-League spot. Businesspersons were invited to set up consortiums in each major city; the clubs were to be funded using private-equity capital; and the league was based around the North American concept of one-team-one-city. The A-League was a classic corporate league as it involved new franchises with no traditions, history, stadiums, social clubs or junior networks. It was clear to everyone that one reason why the A-League was created was to relegate the ethnic clubs from the national stage (to compete in the second-tier in the various state-based premier leagues). The authors argue that the Football Federation of Australia (FFA) used budgeted accounting numbers to exclude the ethnic clubs from the A-League since the ethnic NSL clubs were unable to operate at anywhere near the budgeted numbers being put forward. The "scorched-earth" and "ground-zero" ideology in the air around 2003-05 was pushed ideologically by the FFA (and the conservative Howard government had made government funding conditional upon a major restructuring of the national league) and was used to justify the Brave New World, which was marketed as Modern Football to implicitly contrast it with Old Soccer. Old Soccer was of course unspoken code for the ethnic clubs and their identities based on political rivalries from the other side of the world (most notably Croatia versus Serbia and Greek Macedonia versus FYROM Macedonia).

Projected minimum annual budgets for all A-League aspirants were mandated by the FFA in addition to an imposed minimum AUD1 million of start-up capital [27]. These budgets were: AUD3.5 million to AUD4.5 million per year for the first year, rising to AUD5.5 million a year for the fifth year. Two of the biggest ethnic clubs, South Melbourne and Melbourne Knights (formerly and still informally known as Croatia) had annual revenues of AUD1.8 million and AUD1.2-1.3 million, respectively, in the NSL years, which were good but not good enough to compete.

The authors include some comments from the president and hard-core supporters (ultras) of Melbourne Knights attained through personal and group interviews. A follow-up article by James, Walsh [17] updates the situation and praises the new FFA Cup (modelled on England’s FA Cup), which provides a chance for ethnic ex-NSL clubs to play against A-League clubs, but the authors continue to push for promotion and relegation to and from the A-League. In this new article they use Marx's theory of alienation to contextualize and explain how the ethnic clubs and their supporters are alienated from the A-League. The goodwill of the former NSL and of the clubs has been stolen by the A-League and the ethnic clubs’ invested capital may have begun to devalue and waste as new opportunities for growth have closed themselves off. Melbourne Knights has suffered a four-fold or five-fold drop in revenues to around AUD250,000 a year since the end of the NSL era. Its freehold land in western Melbourne has a high re-sale value but, if the land is not sold, it generates far lower revenues than it did in the NSL years.

One weakness of the study is that it obtains primary data from only one ex-NSL club as no other club responded to the authors’ request for interviews. A second weakness is that the authors are unable to prove that the high budgeting accounting numbers were instituted by the FFA for the purpose of instituting exclusion upon ethnic clubs. A third weakness might be that it is very obvious “which side" the authors take in the Modern Football versus Old Soccer debate.

Research Method

Introduction

This article aims to examine the reporting of CSR activities undertaken by the 12 football clubs competing in the 2016-17 Scottish Premiership. The research employs content analysis.

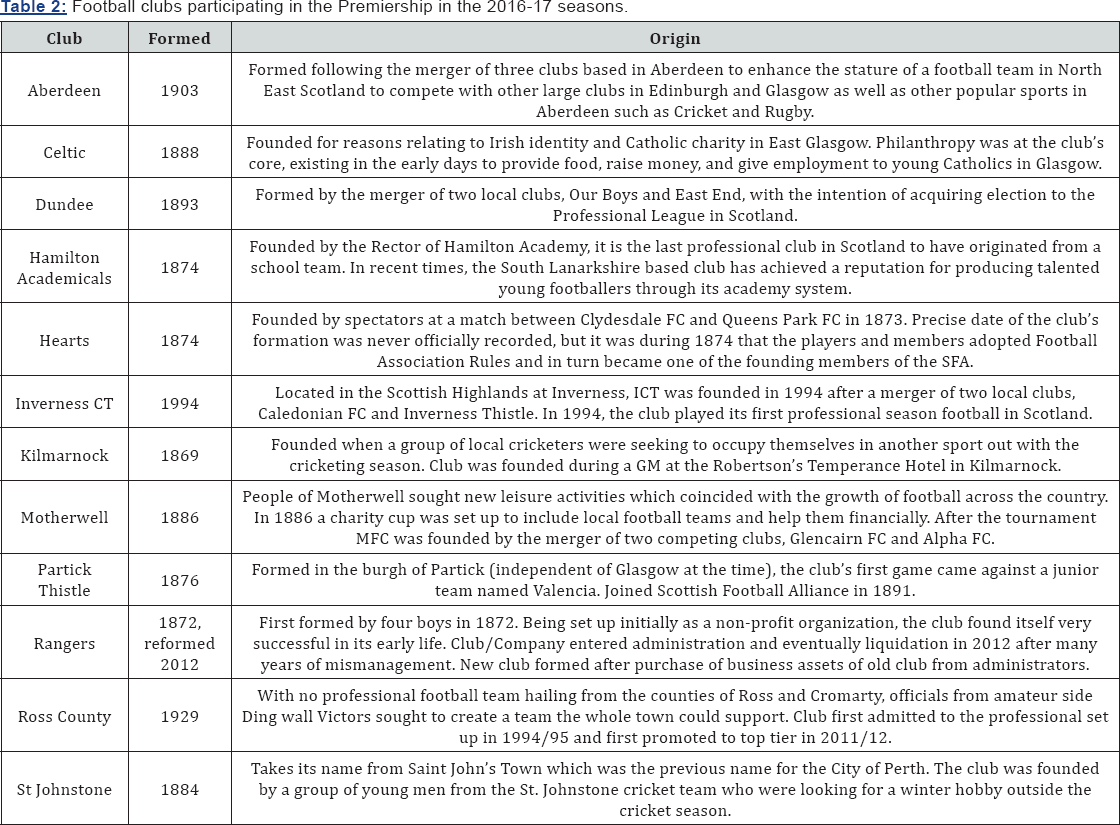

Sample clubs

The study focuses on the 12 clubs participating in the Scottish Premiership in the 2016-17 seasons. This topic takes on added interest because most clubs are socially recognized as having their own distinct characteristics, despite being geographically close to one another. It also seemed like a good season to choose, given that Rangers had been newly promoted to the top-tier. The number of clubs assessed also allows us to obtain a better understanding of the social influences of each football club in its own community across a large geographical area. Table 2 contains background information about the clubs.

Scope of CSR disclosures analysed

Four sources of information were examined: (a) annual reports; (b) official websites; (c) community arms' disclosure; and (d) the SPFL Trust. The selected clubs’ annual accounts were reviewed over the three-year period of 2012-15. The goal of the annual accounts review was to recognize any disclosure of CSR- related activities within each year's annual report. We looked for disclosures of both strategic and descriptive information relating to CSR. Annual Reports for the year 2016 were not included as most clubs had not produced 2016 reports at the time of our fieldwork. An analysis of the clubs’ official websites was also conducted for disclosure of CSR activities using an internet archive tool. A review of information available on the clubs’ community arms’ websites was also undertaken to extract information relating to their CSR activities and potential motivations. The internet archive tool was used to view and browse the community arms’ websites from previous time periods to collect information on their past and continued CSR activities.

Sources: Club official website and community arm websites.

Information from the SPFL Trust was also used to collect information on the clubs' CSR work. Due to the small size of some clubs it is likely that they cannot afford to fund community programmes and disclose them individually. The Trust was set up to help increase clubs' abilities to deliver community engagement programmes.

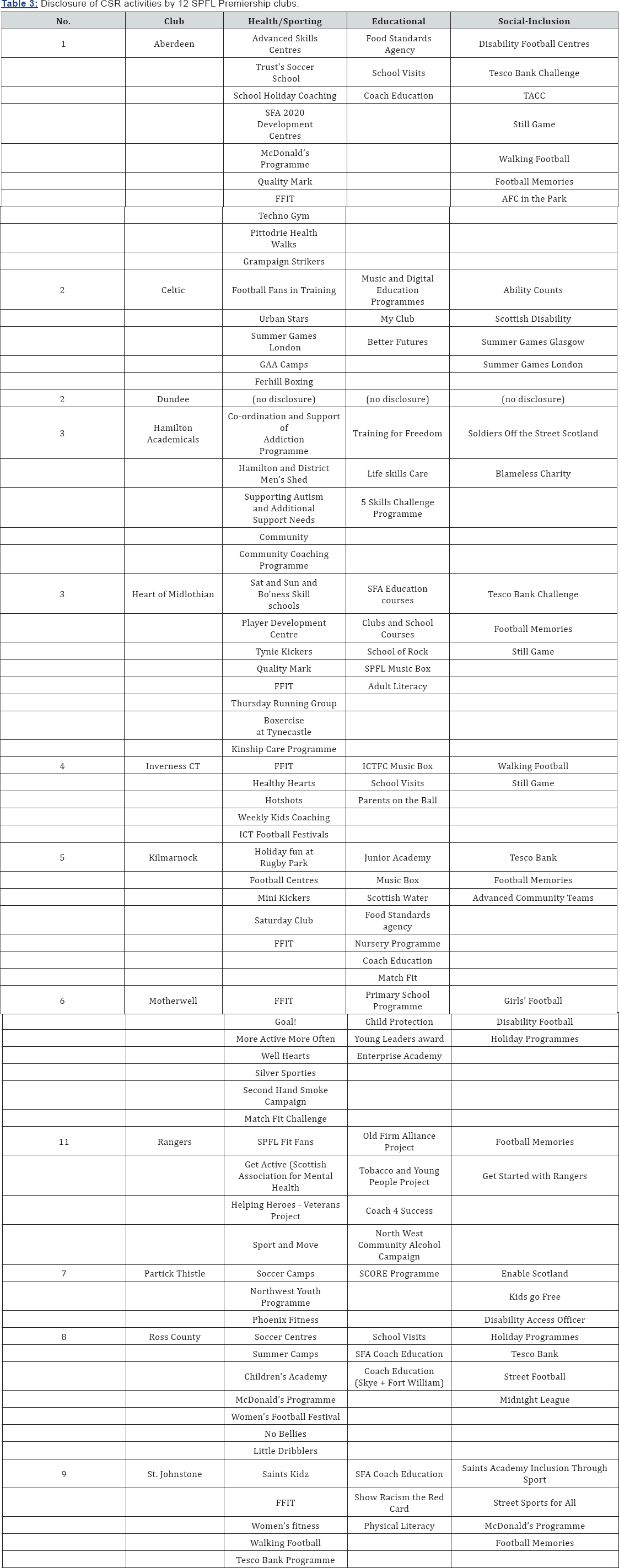

Content analysis

The objective of the content analysis was to categorize disclosure of CSR activities into the following three categories: (a) Health/sporting; (b) Educational; and (c) Social-inclusion. The reasoning for this categorization was to analyse community involvement categorized according to type-of-CSR and to help analyse motivations for engaging in CSR activities. Using GRI standards to analyse the club's activities and disclosures was considered but they are commonly used for larger organizations, using a wider scope than what is expected of Scottish football clubs. It might be argued that our categories are vague but they did help us to distinguish and include most programmes by clubs. The findings are reported in the next section.

Results - CSR Disclosure

Introduction

This section summarizes and analyses the CSR disclosures undertaken by the 12 SPFL Premiership clubs. The complete results are reported in Table 3. Analysis of clubs' annual reports over time showed that most of the top-tier teams did not disclose any CSR-related activities via this format. This is probably due to most clubs filing abbreviated accounts in which they are only obligated to submit due to the sizes of their companies. Another reason may point towards the birth of the SPFL Trust which aims to highlight each SPFL team's community activities separately. Most community trusts associated with Scottish clubs are independent organizations / charities with their boards of directors which may also provide a reason for clubs choosing not to disclose CSR related activities. However, three of the biggest clubs in the Premiership, Aberdeen, Celtic, and Rangers, did provide some level of disclosure in their annual reports from 2012 to 2015.

Annual Reports

Aberdeen: The only club to submit a direct CSR statement within its annual report was Aberdeen FC in 2013. In this statement, Aberdeen disclosed that its community trust was in the process of being formed "to lead and oversee the club's engagement with and delivery of support and opportunity to various local community groups". The CSR Statement stated that: "AFC is committed to working with others to provide support and opportunity and to inspire local communities...In addition to being a participative and identifiable role model, AFC will work to improve health and wellbeing, education and equality and to enhance social inclusion and cohesion". Aberdeen focused on changing lifestyle choices in disclosing that their Trust's vision is: "[t]o provide support and opportunity to change lives for the better" including their trust’s six key purposes: (a) Sports participation; (b) Provision of recreational facilities; (c) Health; (d) Community Development; (e) Equality and Diversity; and (f) Education. Activities in these areas would be identified under the following pillars: Positive Activity; Health and Wellbeing; Equality and Inclusion; Good Citizenship; and Learning Initiatives. Aberdeen in 2015 reported on its CSR activities by stating that the Trust had been a "remarkable success story" and, in just two years of activity, is "making a real impact in so many diverse areas within Aberdeen and the [Aberdeenshire] Shire". Aberdeen did not disclose details of its CSR programmes directly in its annual report.

George Yule, now Vice Chairman at Aberdeen, was appointed as an executive director. He had and has a key responsibility of preparing the club for its relocation to a new football stadium and training complex. Yule is the non-executive Chairman of the Aberdeen Sport Village and he is also involved in local charities in Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire. Yule appears to have been the key in driving the introduction of the Aberdeen FC Community Trust and his remit extends to most parts of the club's activities including the football and commercial sides as well as building and sustaining positive stakeholder relations. In Aberdeen’s 2013 report, Yule stated that the trust: "will continually seek to raise the profile of the North East of Scotland and make use of its key relationships with Aberdeen City and Shire and AFC, while never losing sight of its primary purpose which is to improve the lives of those living and working in the North East of Scotland, and elsewhere" [emphasis added].

In 2014, Aberdeen reiterated that it had continued to make progress with engaging with council authorities in pursuit of building a new stadium and professional training facilities. The £50 million new stadium and training facility was and is planned for Kingsford, close to the Aberdeen bypass, near Westhill, which is well outside the current boundaries of the Aberdeen suburbs as the map of Aberdeen demonstrates. The club management has expressed frustration at the endless delays in the building and moving in to the new stadium although the delays appear to be more due to protest groups and the Aberdeenshire Council rather than the club. Being in a one-team-city the club is like a goldfish in a small bowl and the expectations and pressures are monotonous and severe.

A key stakeholder is the No Kingsford Stadium (NKS) protest group. Traffic and parking issues have been the main areas of concern for protestors and a decision was to have been made by councillors in October 2017 after a pre-determination hearing which was to have taken place on 13 September. However, the council meeting was then postponed until Monday 29 January 2018. The main concerns about the proposed development have been the destruction of greenbelt on the city's fringe; traffic and parking issues on match-days; and the loss felt by long-term supporters in being forced into a move away from the club’s traditional inner-city home ground of Pittodrie [28]. The club believes that new playing and training facilities will help to attract new quality players and higher average home attendances. Football is becoming just another industry and the norms of behaviour and ways of relating from the mainstream business sector have colonized football. At the same time, the fans, although paying much more in cash, have fewer rights and power than ever before.

Another point we should make is that most UK football stadiums were built in old inner-city areas and residents either saw them built in quieter days when modern-style protest groups had not emerged or, in the case of stadiums which were there before residents arrived, the newcomers probably felt they had no moral basis to complain since they had chosen to move into accommodation close to a stadium. The stadium issue has created image management and stakeholder management issues beyond what the Aberdeen-based club probably envisaged during its early planning.

Celtic FC: “Charity lies at the very heart of Celtic; it is part of our DNA". In Glasgow-based Celtic's annual reports of 2013 and 2014, a section headed “Social Responsibility" is provided within the Director's Statement. The short statement informs that the club is “proud of its charitable origins and operates policies designed to encourage social inclusion". Celtic’s annual report in 2013 stated that two of its community arm’s associations, Celtic Charity Fund and the Celtic Foundation, would join forces to create the Celtic FC Foundation. In the 2014 report, Celtic Chairman Ian Bankier stated that the Celtic FC Foundation’s priority is to aid individuals who face daily challenges within the key priority areas of Health, Equality, Learning and Poverty (HELP) as well as supporting external charities which offer value in the community and whose principles fit within the key areas of HELP.

Being financially the strongest club in the country and located in the East End of Glasgow (in the suburb of Parkhead, 4.8 kilometres east of the city-centre), Celtic does not need to look too far to find motivating factors to undertake CSR activities. The club's 2013 annual report states that it “was built on charitable foundations" and that it “continue[s] to recognise the importance of that ethos and the Club’s role in society." The report also, when outlining its social aims, claims that the Celtic Charity Fund, formed in 1995, was founded to support causes based on (Roman Catholic) Brother Walfrid's founding principles. Celtic's [29] report on the Foundation states that the club had “made great progress in securing longer term funding" for its current projects and that it had several long-term applications about to be submitted. The club said this would ensure sustainability of its work and longer term support for the communities which it is serving. The year 2014 provided Celtic with an opportunity to showcase to the world through hosting the opening ceremony of the Commonwealth Games [30-32]. In a bid to improve the area of the Games, Glasgow City Council and other authorities helped Celtic transform the areas around Celtic Park. It could be argued that Celtic’s CSR work in the community since 1995 allowed it to host the ceremony as well as win favours from local government authorities for other ventures.

Celtic’s Ability Counts CSR programme aims at educating, developing, and engaging with people with Down's syndrome. The club now employs several individuals, who were first involved with the club through this programme, as Celtic Park tour guides [33,34].

Rangers: In 2013, whilst Rangers was playing in League One (third-tier), it still recognized its impact on the community by disclosing some of its CSR work within its annual report. (Rangers are based at Ibrox, 4.0 kilometres west of the Glasgow city-centre.) The club admitted in its 2013 annual report that “there is a social responsibility side" to Rangers even though its primary aim is to provide a standard of player able to compete for trophies and medals. In 2013 Rangers stated that it had 20 ongoing community projects, which mostly require funding, but that a club the size of Rangers should not forget that it has a responsibility to “change lives for the better". In 2014 and 2015 Rangers quantified some of the social activities it participated in. Both years saw the club visit over 60 schools throughout Glasgow and the West of Scotland educating children on antisocial behaviour. In both years Rangers said that it engaged with more than 450 primary-school children in educational projects surrounding drugs and adolescence; and in 2015 disclosed that it benefitted 600 young people through courses organized by the Rangers Study Centre.

In 2015, after changes in the boardroom, Rangers said that while it “must always recognise community responsibilities" the focus must be on the football department which the club said “will be judged most, so everything that can be done to make Rangers successful must be done". However, it recognized that its intention is to be successful “with style as well as the levels of pride and dignity which should always be part of Rangers ['] ethos." This seems to mark a slight de-emphasis on and retreat from CSR perhaps because, being then part of the second-tier Championship and near the Premiership, it had begun to feel the pressures arising from its absence at the higher levels and had wanted to lower and manage expectations. Without strong on-field performance the energy around the club would become negative and CSR redundant and a case of spreading resources around in too many diverse places.

In its 2015 Supporters Charter, Rangers highlighted that, through its Foundation, it aims to improve the “wellbeing and lifestyle choices of [military] veterans struggling with mental health issues, addictions or social isolation" as well as donating sums to other army related charities. Some of Rangers’ CSR activity, such as support for military veterans and education programmes for school-children about drugs and bullying, is consistent with the traditional self-conscious Britishness and Protestant work-ethic of the club. The charter also provides detailed information about Rangers' community partnerships with children's hospitals and Alzheimer's Scotland. Rangers [35] liquidation (and rebirth via new company Sevco Scotland Limited) harmed its public image in the eyes of not only the football community but also governmental and council authorities. In its 2015 Business Review Rangers laid out that it intends to re-engage with its supporters, football authorities, and government. Overall Rangers appears to be more pragmatic and circumspect about its CSR activities as compared to Celtic which is now a club imbued with optimism and energy due to its long unbeaten record in Scottish domestic matches (as at 31 October 2017) and the influxes of Champions' League cash it has been receiving. In contrast to the high-flying and exuberant Celtic, Rangers has just emerged from liquidation and then the lower-tiers of Scottish football (the punishment imposed upon it for its liquidation) and wants to rebuild quietly on and off the field without attracting undue attention. The internationalist left-wing radicalism of part of Celtic's hard-core supporter base (as evident in the Palestinian flags seen at matches) is not to be found at Rangers.

External disclosure

a) Community arm disclosure

The community arms of some of the clubs can be recognized as important divisions of their CSR programmes. However, Panton [36] suggests that football clubs cannot outsource all of their CSR responsibilities and must have regard to their own companies' impacts on communities. Most of the separate community schemes are run as charitable organizations and are sustainable even when independent of the actual football clubs. Most of the arms, such as the Celtic FC Foundation and the Aberdeen FC Charitable Trust (AFCCT), have, since becoming independent, increased in size over the years to generate more revenue and they have increased the number of projects that they provide. A resolution passed at Aberdeen's [37] AGM saw the AFCCT receive a 9% shareholding in the club "by way of gift" and thus it became a stakeholder of the club itself (and viceversa).

SPFL Trust: In 2009 the SPL (Scottish Premier League Trust) was launched to source funding to co-ordinate community initiatives across the 12 Premiership clubs. After league reconstruction, the SPFL Trust was created in 2013. It is an independent registered charity and works in partnership with all 42 clubs competing across all four divisions of the SPFL. The Trust’s work extends into 22 local authority areas and reaches communities making up almost 85% of Scotland's population (SPFL, 2013). For this research only data from the 12 2016-17 Premiership clubs was collected.

a) SPFL Trust Legacy 2014 Report

In 2016 the SPFL produced a 2014 legacy report, following the Commonwealth Games, on its activities since having received funding from the Scottish Government. The community programme was the biggest in Scottish football history and revealed that over 30,000 people were engaged at a cost of £500,000 [38]. In all, 40 of the 42 clubs took part in the programme including all subject clubs included in this research. Each club or its community arm was invited to apply for a grant of £11,000 to deliver a programme of activity with engaged people in need or those in often hard places to reach. The report recorded the number of people engaged by each club over 2013 and 2014 as well as how many programmes were delivered and a summary of their programmes’ achievements.

Disclosure of CSR activities

Introduction

It is important to note that Dundee FC did not provide any disclosure of CSR activities from 2013-16. This is somewhat surprising because, although Dundee is a smaller club than Aberdeen, Celtic, Hearts, Hibernian, and Rangers (as measured by average home attendances), it is larger than some clubs who did disclose their CSR activities such as Hamilton, Inverness, Kilmarnock, Motherwell, Partick Thistle, and Ross County. Furthermore, Dundee FC is based in a deprived area (Table 1) and so arguably has more ethical obligations to undertake and disclose CSR activities.

Ross County FC

Ross County is a Highlands club, based in Dingwall (population 5,491), 291 kilometres north of Glasgow and 9.65 kilometres north-west of Inverness. It was a Highland League club up to 1993-94 but secured rapid promotion through the tiers to the Premiership in 2012-13 and has remained there ever since. Its biggest honour in Scottish foot ball has been winning the 2015-16 League Cup (The Wee Red Book 2017-2018 Football Annual, p. 78). It has been bankrolled by businessman chairman Roy Mac Gregor. The club still serves a small population base and it attracts very few fans from outside its large catchment area. Ross and Cromarty is 8,019 km2 in area, the third out of 34 Scottish regions in size, and Dingwall is the traditional county town for what was formerly Ross-shire (1890-1975). Scotland as a whole only covers 77,933 km2, meaning Ross and Cromarty covers 10.29% of the total land area. In 2016-17 Inverness Caledonian Thistle, based only 9.65 kilometres away, was also in the Premiership but it has since been relegated to the Championship.

Due to the rivalry between these two Highland clubs, Ross County is unlikely to be able to attract many new sponsors or supporters from Inverness or from Inverness-supporting districts. This puts a limit on any expansion hopes it might hold and forces it to serve diligently its local district both in pure footballing terms and in terms of CSR activities. Ross County FC is an interesting mini-case study due to the small (in population) and rural nature of its local heartland constituency which contrasts starkly with the city clubs located in Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, and Glasgow. In 2013 Ross County stated that being part of the Highland Community is something the club takes very seriously and that its community department is important in introducing the club's values and principles to children, parents, and other stakeholders in the Northern region. The club described its activity programmes’ prime objectives as focusing on fun for the participants and helping them develop important skills. It also puts emphasis on other important social aspects such as health, respect, education, and safety. Ross County commented that its commitment to covering a large geographical area (8,019 km2) requires that its community team travel to obscure places and help those in need.

Discussion

This article has examined the reporting of CSR activities undertaken by the 12 football clubs competing in the 201617 Scottish Premiership. The data on the clubs' CSR activities was explained based upon contextual factors such as historical and cultural foundations; economic factors; and geographical locations. Aberdeen FC, with the appointment of a specific director in 2013, shows a clear level of stakeholder engagement and this director has, without doubt, influenced the implementation of CSR-related activities. Aberdeen’s focus of appointing a director and awarding free shares to its Community Trust also highlights the push to be seen as a legitimate and sustainable business as it tries to expand the club with new facilities. The delays to the new stadium, due to a cautious council and a residents’ protest group, has frustrated the club’s efforts to get the new stadium and training facility up and running. The strongest club in the country at present, Celtic, bases its CSR policies and activities on its Irish-Catholic founding ethos (which arguably has now morphed into more generalized left-wing radicalism as evidenced by Palestinian flags being waved by supporters at matches) and its founding principle of charity. The size of the club, both in terms of finance and support, has also allowed extensive work to be carried out by its Foundation.

Everything Celtic does at the present time is imbued with optimism and pride due to its long unbeaten record in Scottish domestic matches and the influxes of Champions’ League cash it has been receiving. It is subject to jealousy from fans of rival clubs and perhaps the club itself is riding on a wave of euphoria which might have been diluted and muffled by the presence of strong opposition in earlier times. In late September 2017 it received approval for its new visionary £18 million hotel and museum development (which will allegedly create 120 new jobs). Glasgow City Council approved the new development planned adjacent to Celtic Park which puts Celtic’s smooth ride in sharp contrast to the difficulties and setbacks experienced by Aberdeen in the north-east of the country. Overall Rangers appears to be more pragmatic and circumspect about its CSR activities as compared to Celtic. Rangers has just emerged from liquidation and then the lower-tiers of Scottish football (the punishment imposed upon it for its liquidation) and wants to rebuild quietly on and off the field without attracting undue attention. Rangers are lagging behind Celtic on all counts including on the football field and in terms of CSR activities and disclosure.

We should note that some of Rangers’ CSR activities, such as its work with military veterans and educational programmes for school-children about drug-abuse, fit in well with the club’s traditional Britishness and Protestant work ethic and conservatism. The internationalist left-wing radicalism of part of Celtic's supporter base is not to be found at Rangers.

Medium-sized club Hearts, as well as smaller clubs Kilmarnock, Ross County, and St. Johnstone, have demonstrated an understanding of their stakeholders’ pressures. The commitment to engage with the interests of these specific stakeholders can be a vital feature of a club’s marketing and corporate philosophy. Lau et al. [39] write about the increasing number of factors that are leading football clubs to implement CSR activities and side-arm organizations. It is evident that this has been the case with our sample clubs. Within the last five years, Aberdeen, Kilmarnock, Motherwell, and St Johnstone, in particular, have focused on implementing new programmes and expanding their community and charity work in their partner organizations or within their internal community departments (Table 3) [40-45].

Conclusion

This research study shows that although Premiership clubs can expect to receive a variety of benefits for engaging in beneficial social programmes including government grants, supporter goodwill, and a projection of being a legitimate business, other factors come into play when understanding the motivations for each club. Some clubs' founding principles and general size almost obligate them to partake in CSR. For example Celtic, being by far the wealthiest club in the country, and with the most media coverage, takes part in a variety of CSR programmes at home and abroad. This differs from small and remote rural clubs such as Ross County, which like Celtic partake in many activities, but their motivations focus on developing the business going forward rather than obvious pressures from outside the organization. Every club has specific reasoning for their implementation choices. Furthermore, Marxism helps us to understand the context and process factors better as football at the top level moves further and further away from its community (feudal / neighbouring town-versus-neighbouring town) roots towards higher and higher stages of capitalism [46-52].

Dedication

This paper is dedicated to the late Pastor Alexander Reid (1936-2016) of New Life Church, Paisley, and Renfrewshire, Scotland who was widely respected in the local community for his faith, compassion, and good cheer.

References

- James K (2017) Symbols, heroes, rituals, and values at East Perth Football Club, 1956-61 (with special thanks to Sister Kate’s Home). Unpublished working paper, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, Scotland.

- Hamil S, Morrow S (2011) Corporate Social Responsibility in the Scottish Premier League: Context and motivation. European Sport Management Quarterly 11(2): 143-170.

- Cloake M (2014) Community is the core of football and with it notions of identity and place. SportingIntelligence.

- Supporters Direct (2010) The Social and Community Value of Football.

- Marx KH (1976) Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume I: The Process of Capitalist Production [1867].

- Cooper C, Johnston J (2012) Vulgate accountability: insights from the field of football. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 25(4): 602-634.

- Cooper C, Joyce Y (2009) The marriage of Bourdieu and private ordering on Gretna's football field. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Accounting Conference.

- Cooper C, Joyce Y (2013) Insolvency practice in the field of football. Accounting, Organizations and Society 38(2): 108-129.

- James K, Tolliday C, Walsh R (2011) Where to now, Melbourne Croatia? Football Federation Australia's use of accounting numbers to institute exclusion upon ethnic clubs. Asian Review of Accounting, 19(2): 112124.

- Grant N, Heere B, Dickson G (2011) New sport teams and the development of brand community. European Sport Management Quarterly 11(1): 35-54.

- Crawford K (2016) Dumbarton: part-time sons still surviving in Scotland's second tier. BBC Sport.

- Grahame E (2012) Ayr United's Brian Reid looks to play bigger part. The Telegraph, UK.

- Waddell G (2015) Brechin City boss Ray McKinnon has no time for whingeing full-time clubs as his squad makes do on the football breadline. Daily Record Online, UK.

- Ferrante J (2013) Sociology: A Global Perspective. p. 1-432.

- Fischer E (1973) Marx in His Own Words.

- Israel J (1971) Alienation: From Marx to Modern Sociology: A macrosociological analysis.

- James K, Walsh R (2017) The expropriation of goodwill and migrant labour in the transition to Australian football's A-League. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing.

- Marx KH (1994) Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts. Indianapolis p. 54-97.

- Ollman B (1976) Alienation: Marx's Conception of Man in Capitalist Society. Cambridge University Press, USA.

- Armstrong G (1999) Football Hooligans: Knowing the Score. Social Anthropology 7(3): 335-349.

- Marx KH (1975) Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts. pp. 279400.

- Marx KH (1981) Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume III: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole.

- Trotsky L (2004) The Revolution Betrayed: What is the Soviet Union and where is it going?. Dover Publications, New York, USA.

- Eagleton T (2002) Marxism and Literary Criticism. London.

- Gannon M (2017) Hoops pricing kids out of the biggest games. p. 65.

- Solly R (2004) Shoot Out: The Passion and Politics of Soccer's Fight for Survival in Australia, John Wiley & Sons, Milton, Brisbane, Australia.

- Mc Gowan S (2018) New stadium is utopia we crave at Dons. Scottish Daily Mail p. 80.

- Celtic (2014) Celtic Football Club Plc. Annual Report.

- Aberdeen (2013) Aberdeen Football Club Plc. Annual report.

- Aberdeen (2015) Aberdeen Football Club Plc. Annual report.

- Celtic (2013) Celtic Football Club Plc. Annual Report.

- Celtic (2015) Celtic Football Club Plc. Annual Report.

- Celtic (2016) Celtic Football Club Plc. Half-year (Jun-Dec) interim report.

- Rangers Charity Foundation (2012) In the Community.

- Panton M (2012) Football and Corporate Social Responsibility. Birkbeck Sport Business Centre Research Paper Series 5(2).

- Aberdeen (2014) Aberdeen Football Club Plc. Annual report.

- SPFL (2016) SPFL Trust Legacy Report.

- Lau N, Makhanya K, Trengrouse P (2004) The Corporate Social Responsibility of Sports Organizations: The Case of FIFA. International Centre for Sports Studies, Switzerland.

- Rangers (2013) The Rangers International Football Club Plc, Annual Report.

- Rangers (2014) The Rangers International Football Club Plc, Annual Report.

- Rangers (2015) The Rangers International Football Club Plc, Annual Report.

- Rangers (2016) The Rangers International Football Club Plc, Half-year (Jun-Dec) interim report.

- Scottish Index for Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) (2016) Scottish Index for Multiple Deprivation.

- SPFL (2013) Funders.

- Bryer RA (1995) A political economy of SSAP22: Accounting for goodwill. British Accounting Review 27(4): 283-310.

- Bryer RA (1999) A Marxist critique of the FASB's conceptual framework. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 10(5): 551-589.

- Bryer RA (2006) Accounting and control of the labour process. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 17(5): 551-598.

- James K, Tolliday C (2009) Structural change in the music industry: a Marxist critique of public statements made by members of Metallica during the lawsuit against Napster. International Journal of Critical Accounting 1(1-2): 144-176.

- James K, Tolliday C (2017) Metallica, Kieran James, Renfrewshire, Scotland.

- Marx KH, Engels F (1992) The Communist Manifesto, Random House, New York, USA.

- Mihret DG, James K, Mula JM (2010) Antecedents and organizational performance implications of internal audit effectiveness: some propositions and research agenda. Pacific Accounting Review 22(3): 224-252.

- Tinker T (1999) Mickey Marxism rides again!. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 10(5): 643-670.