Introduction

Internal and external dynamics in this moment are converging, creating unprecedented pressures on health systems. Rapid technological innovation promises transformative treatments while straining already limited budgets. Political and economic volatility creates uncertainty in funding commitments and policy priorities. Demographic shifts increase demand for health services while workforce constraints remain one of the key factors limiting the expansion of health services. Against this backdrop, critical health system components-innovation pipelines, investment mechanisms, value assessment frameworks, financing structures, infrastructure information systems, accountability mechanisms, and implementation pathways-lack an integrated governance and continue to be operated largely independently, each for its own objectives with insufficient coordination.

This fragmentation creates inefficiencies and prevents the realization of system-wide synergies. The consequences manifest across health systems, where fragmentation leads to reduced access to services that are often poor in quality, the inefficient use of resources, an increase in production costs (what it costs to produce health outcomes and healthcare outputs), and low user satisfaction [1]. Innovations developed through substantial investment often fail to demonstrate value in ways that align with payer expectations and patient preferences, while interventions shown to be effective and economical frequently remain unfunded. Policies enacted at the national level fail to translate into patient access at the point of care. The result is suboptimal health outcomes, wasted resources, and frustrated stakeholders across the ecosystem [2,3].

Yet, comparatively limited attention has been given to recognition of policy as the fundamental architecture that determines how system components interact and function together. Fragmentation in health systems is an enduring challenge that persists despite numerous efforts to achieve better coordination, undermining the effectiveness of health programs and threatening the attainment of health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [4]. Policy is not simply a set of rules to navigate or barriers to overcome. Rather, policy constitutes the structural connective tissue that enables-or preventscoordination, alignment, and value creation across the health ecosystem.

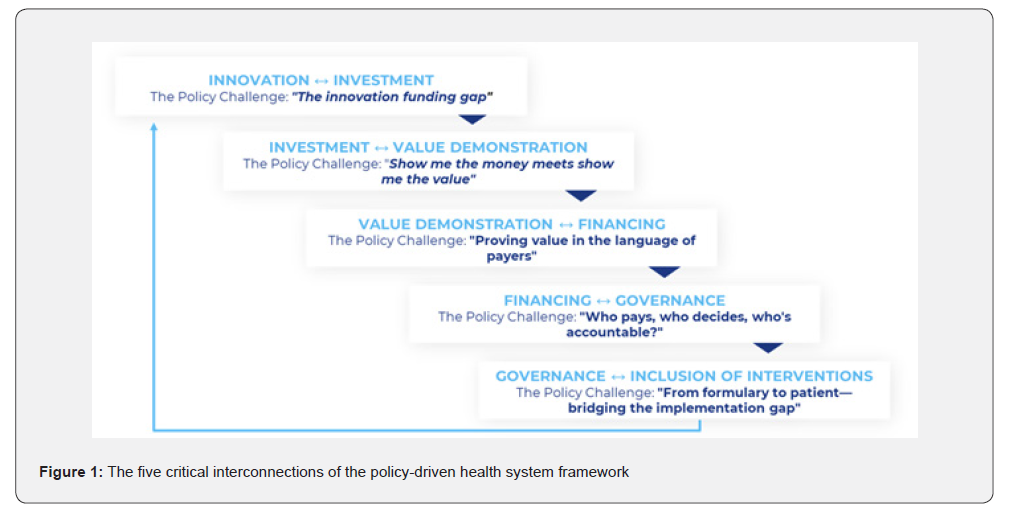

This paper introduces the Policy-Driven Health System framework, which systematically maps five critical interconnections where policy architecture is essential for system coherence. The framework builds on systems-thinking approaches to health systems strengthening [5,6] while extending beyond general governance and systems theory to provide specific, actionable guidance on policy architecture [7,8]. For each interconnection, this paper identifies the specific policy challenges, analyzes the policy levers to address it and how the components must integrate across boundaries. System coherence matters because failures at these interconnections translate into real-world consequences: delayed patient access, inefficient public spending, and missed opportunities to translate innovation into improved health outcomes at scale.

This architectural perspective is particularly urgent in the current period of health system transformation. The year spanning 2025-2026 has been characterized by heightened governance volatility, accelerating adoption of artificial intelligence and data-driven technologies, and sustained fiscal pressure across health systems, all of which amplify the consequences of policy misalignment across domains. Existing approaches-whether systems-thinking, governance reform, or domain-specific policy instruments-tend to focus on individual system components or institutional functions, but rarely specify the policy mechanisms required to connect them. As a result, health systems often lack explicit “interconnection policies” capable of translating innovation, investment, and value assessment into coherent financing, governance, and implementation outcomes.

The Central Problem: Fragmentation in a Complex System

Contemporary health systems exhibit a paradox: increasing sophistication in individual components coupled with decreasing coherence at the system level. For instance, innovation in medical technologies proceeds at an unprecedented pace, generating new diagnostic tools, therapeutic interventions, and delivery mechanisms. Investment in health research and development reaches record levels, both from public and private sources. Value assessment methodologies grow more sophisticated, incorporating cost-effectiveness analysis, multi-criteria decision analysis, and real-world evidence. Despite, or perhaps because of, this increasing complexity, the system fragments.

A critical but often overlooked driver of healthcare failings is fragmentation: interventions target individual parts without adequately appreciating their relationship with each other and their impact on the broader evolving system [9]. Underlying current healthcare failings is a critical yet underappreciated problem: fragmentation-focusing and acting on individual components without adequately appreciating their relationships with each other and with the evolving system as a whole [9]. Each component develops its own logic, metrics, institutional structures, stakeholders, and optimization strategies with limited regard for system-level implications. These locally rational optimization strategies, while sensible from each actor’s perspective, result in collective irrationality at the system level. This occurs because different actors operate with fundamentally different objectives: researchers optimize for scientific advancement, investors optimize for financial returns, value assessors optimize for methodological rigor, payers optimize for budget constraints, and governance bodies optimize for political acceptability.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed how fragmented governance, policies, and investments in health hamper effective crisis response. Similar patterns of fragmentation are evident beyond emergencies, including clinical innovations that fail to reach all patients who could benefit, continued neglect or deprioritization of diseases with high socioeconomic and quality-oflife burdens, unequal access to essential services within countries, and inconsistent implementation of evidence-based guidelines across regions. Although these outcomes reflect rational decisionmaking within individual domains, together they result in collective irrationality at the system level. These failures are not merely operational inefficiencies that can be resolved through improved project management or clearer communication; rather, they reflect fundamental architectural flaws in how health systems are conceptualized, designed, and governed.

The central insight of the Policy-Driven Health System framework is that these boundaries require policy bridges. Systems-thinking has increasingly become a common language in publications concerned with identifying solutions to improve population health more efficiently and equitably [5,6]. However, moving from theoretical appreciation of system complexity to practical application requires explicit policy architecture spanning these boundaries. Health policy-defined as the rules, norms, and institutions that govern health system operation - provides the primary mechanism capable of coordinating the key components and functions across these domains.

A useful comparator is the World Health Organization’s Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach, defined as

“An approach to public policies across sectors that systematically takes into account the health implications of decisions, seeks synergies and avoids harmful health impacts in order to improve population health and health equity.” [9] -Helsinki Statement on Health in All Policies 2013; WHO (WHA67.12) 2014.

HiAP has been particularly influential in strengthening wholeof- government attention to health, equity, and accountability across non-health sectors and levels of government [10]. However, HiAP is primarily designed to ensure that health and equity considerations are integrated into policy-making across sectors; it does not typically provide a detailed operational map of the internal interfaces through which core health system functions (innovation, investment, value assessment, financing, governance, and implementation) must be linked to ensure efficiency, reduce fragmentation and translate decisions into consistent access [11].

The Policy-Driven Health System framework builds on this governance foundation by specifying a set of “interconnection policies”: the concrete policy mechanisms at critical system boundaries that enable coordination between these functions and reduce the gaps that persist despite advances within individual domains.

The Five Critical Interconnections

The Policy-Driven Health System framework identifies five critical interconnections where policy architecture is essential for system coherence, as seen in Figure 1 below. Each interconnection represents a boundary between major health system functions where fragmentation commonly occurs, and where policy provides the necessary connective tissue. For each interconnection, this paper identifies the core policy challenge and presents the critical policy components required to address it.

Innovation-Investment: Bridging the Innovation Funding Gap

The innovation-investment interconnection addresses how research and development (R&D) activities secure financial resources in ways that align with health system priorities. The policy challenge is the innovation-funding gap-the disconnect between scientific opportunities and available capital, exacerbated by both trial outcome uncertainty and policy uncertainty that makes return on investment unpredictable. Despite significant increases in support for global health and innovation over the previous decade, growing pressure on traditional funding channels has driven attention toward innovative financing mechanisms (e.g. risk sharing agreements and public-private partnerships) to supplement conventional funding [12].

Critical Interconnection Policy Components

R&D incentive frameworks establish financial architecture supporting innovation. Tax credits for research expenditure reduce the cost of innovating. Patent extensions provide extended market exclusivity for innovations addressing unmet needs. Orphan drug designations offer regulatory and market advantages for rare disease treatments. Priority review vouchers create tradeable benefits for innovations in neglected areas. These incentives do not simply subsidize research; they shape investment decisions by altering the risk-return calculus in specific therapeutic areas.

Regulatory pathways determine the evidence requirements and timelines for innovation approval, directly affecting investment risk. Adaptive licensing allows conditional approval based on preliminary evidence with post-market confirmation, reducing upfront evidence costs while maintaining safety oversight. Accelerated approval mechanisms provide faster market access for innovations addressing serious conditions, shortening time to revenue.

Public-private partnership models pool risks and resources across sectors. Pre-competitive collaboration frameworks enable the sharing of foundational research, tools, and methodologies without compromising competitive positioning. Translational research funding supports the high-risk transition from basic science to clinical application where private capital is reluctant to invest. When these policy mechanisms are misaligned or absent, scientific opportunity fails to translate into sustained investment, leaving promising innovations underdeveloped despite clear health system need.

Investment-Value Demonstration: Show Me the Money Meets Show Me the Value

The investment-value demonstration interconnection addresses how research investments generate evidence that demonstrates value to health systems. Health technology assessment has become increasingly important as a bridge between research evidence and health policy, providing policymakers with evidence to inform decision-making and develop guidance on reimbursement and administration of new health technologies [13]. The policy challenge is ensuring that investments in innovation include investments in value generation, with evidence produced in forms and within timeframes that align with health system decision-making requirements.

Critical Interconnection Policy Components

Value-based resource allocation mechanisms link investment decisions to anticipated value creation. Budget allocation formulas incorporating cost-effectiveness thresholds ensure resources flow preferentially to interventions expected to deliver health system value. Investment prioritization based on comparative effectiveness evidence directs limited resources to innovations with demonstrated superiority over existing options. This also embeds at its core considerations related to key outcomes, ensuring the optimal resource allocation based on the available technologies

Building on adaptive regulatory approaches such as adaptive licensing and conditional approval, evidence-conditioned funding creates dynamic feedback between investment and value generation. Phased investment contingent on interim value demonstration reduces risk by gating continued funding on emerging evidence. Coverage with evidence development policies provides provisional reimbursement while additional evidence is generated, aligning market access with evidence maturation.

Managed Entry Agreements (MEAs) formalize risksharing during evidence development. MEAs are arrangements between firms and healthcare payers that allow for coverage of new medicines while managing uncertainty around their financial impact or performance [14]. Performance-based risksharing arrangements tie reimbursement levels or volumes to demonstrated outcomes, aligning manufacturer and payer incentives [15]. Outcomes-based contracts link payment directly to measured value delivery, transferring performance risk from payers to manufacturers.

Effective policy architecture at this interconnection is therefore essential to ensure that investment decisions generate evidence capable of informing subsequent financing and reimbursement choices.

Value Demonstration-Financing: Proving Value in the Language of Payers

The value demonstration-financing interconnection addresses how evidence of intervention value translates into reimbursement decisions and pricing. The policy challenge is ensuring value assessments produce outputs that directly inform financing decisions, acknowledging that different payers define and measure value differently based on their specific constraints and objectives. Innovation in pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, and med-tech (hereafter referred to as health technology companies) is commonly rewarded by payers agreeing to a premium price for a new health technology, widely seen as stimulating innovation while at the same time delivering value for money [16].

Critical Interconnection Policy Components

Payer-aligned value frameworks ensure value assessments use metrics and thresholds relevant to actual financing decisions. Cost-effectiveness thresholds reflecting actual fiscal constraints provide realistic benchmarks rather than theoretical ideals. Budget impact assessment using payer-specific cost structures accounts for actual prices paid, patient volumes, and displacement effects rather than theoretical models.

In many health systems, the translation of value into financing is further complicated by limited price transparency, as confidential discounts, rebates, and managed entry agreements mean that published list prices often diverge substantially from the net prices paid by public payers, constraining comparability and external assessment of value for money.

Multi-dimensional reimbursement criteria acknowledge that financing decisions consider factors beyond cost-effectiveness. Multi-criteria decision analysis frameworks explicitly balance clinical effectiveness, economic impact, ethical considerations, and organizational factors. Explicit weighting of value elements makes transparent how different value dimensions trade off against each other in financing decisions [17].

Dynamic pricing mechanisms recognize that value and price can vary across uses and over time. Indication-based pricing reflects that the same product delivers different value in different patient populations. Volume-based discounting manages budget impact by reducing per-unit prices as utilization increases. Outcomes-based rebates make final prices contingent on demonstrated real-world value delivery.

When value demonstration is not aligned with payer decision rules, price signals, and real-world constraints, financing decisions risk prioritizing affordability over value or value over affordability, undermining both efficient resource allocation and equitable access.

Financing-Governance: Who Pays, Who Decides, Who’s Accountable

The financing-governance interconnection addresses how financing mechanisms relate to decision-making authority and accountability structures. The policy challenge is ensuring that those who pay, those who decide how resources are used, and those accountable for outcomes operate within coherent frameworks that balance multiple legitimate interests (patients, payers, providers, and industry, among others) while maintaining system integrity.

Critical Interconnection Policy Components

Decision-making authorities establish a clear relationship between financing and governance. Legal frameworks defining financing versus governance roles prevent authority ambiguity and associated conflicts. Separation of payer and regulatory functions avoids conflicts of interest where the same entity both pays for interventions and determines their safety and efficacy.

Participatory governance in financing ensures decisions reflect diverse stakeholder perspectives. Multi-stakeholder representation on reimbursement committees includes patients, providers, payers, industry, and civil society alongside technical experts. Patient and provider input mechanisms enable those affected by financing decisions to contribute to deliberations. Accountability and transparency mandates ensure financinggovernance interfaces operate with public oversight. Public disclosure of coverage decision rationales enables scrutiny of how evidence and values combine to reach reimbursement decisions. Appeals processes for financing decisions provide recourse when stakeholders believe errors occurred. Absent coherent policy architecture between financing and governance weakens accountability and compromises the legitimacy, sustainability, and consistency of health system decisions.

Governance-Inclusion of Interventions: From Formulary to Patient

The governance-inclusion interconnection examines how national-level decisions on intervention inclusion translate into patient-level access. The central policy challenge is the implementation gap: the often-substantial distance between formal adoption at the national level and the timely, appropriate availability of interventions at the point of care. The policy objective is to design governance mechanisms that reflect systemspecific organizational realities, recognizing that integration processes are inherently complex, resource-intensive, and longterm [1].

Critical Interconnection Policy Components

Cascading implementation mandates the creation of automatic mechanisms, translating national decisions into subnational action. Automatic triggers linking national formulary inclusion to subnational implementation requirements eliminate implementation delays caused by passive diffusion. Timelines for reimbursement decisions following guideline updates prevent indefinite gaps between clinical recommendations and financing availability.

Multi-level governance coordination ensures vertical integration from the national to the facility level. Vertical integration mechanisms create information flows and coordination processes spanning governance tiers. Inter-governmental agreements on implementation responsibilities clarify which governance levels handle different implementation tasks.

Implementation capacity policies ensure necessary prerequisites exist before interventions are added to formularies. Infrastructure readiness assessments before formulary inclusion prevent adoption of interventions that cannot be delivered. Conditional listing mechanisms allow interventions to be introduced in phases as implementation capacity develops, avoiding situations in which formal access exists on paper but cannot be realized in practice.

When governance and implementation are not explicitly connected through these mechanisms, inclusion decisions fail to translate into effective access, leaving approved interventions unavailable to patients despite formal coverage.

The Value of Policy Architecture: A Multi-Stakeholder Perspective

Systematic engagement with policy architecture offers significant value across the health system by reducing inefficiencies, improving coordination, and enabling more effective translation of innovation into patient benefit. The difference between fragmented and integrated approaches to policy interconnections manifests in concrete outcomes that affect all health system stakeholders.

From Reactive Adaptation to Anticipatory Coordination

When stakeholders operate without understanding policy interconnections, the system responds reactively to policy changes. Regulatory shifts, reimbursement decisions, or governance reforms generate cascading adjustments across multiple actors, creating inefficiency and uncertainty. Each stakeholder develops contingency strategies independently, duplicating analytical efforts and often working at cross-purposes.

Systematic understanding of policy architecture enables anticipatory coordination. When multiple stakeholders understand how policy components interconnect, they can engage constructively in policy development processes, reducing implementation friction and improving policy effectiveness. This produces more stable policy environments and reduces the transaction costs of policy change for all system participants.

From Evidence Misalignment to Evidence Integration

A common system inefficiency emerges from disconnected evidence generation. Clinical trials designed for regulatory approval often fail to generate evidence needed for reimbursement decisions, requiring additional studies that delay patient access and consume research resources. Value assessors require economic evidence, budget impact analyses, real-world effectiveness data, and patient-relevant outcomes frequently absent from regulatory trials.

Understanding the value of demonstration-financing interconnections enables evidence integration. When evidencegenerators, regulators, and payers coordinate evidence requirements early in development, single research programs can serve multiple policy functions. This reduces redundancy, duplication of effort, accelerates patient access, and improves the efficiency of research investment across the system.

From Isolated Decision-Making to Portfolio-Level Policy Risk Management

Without the strategic and systemic policy foresight described in the Policy-driven Health System Framework, decisions about research priorities, development investments, and resource allocation occur in isolation from policy evolution. Pricing reforms, value assessment methodology shifts, or implementation barriers can systematically affect multiple programs simultaneously, creating concentrated policy risk that affects not only commercial actors but also public research institutions, healthcare providers, and ultimately patient access.

Policy architecture understanding enables more sophisticated priority-setting that considers policy dynamics. By analyzing how different therapeutic areas, patient populations, and intervention characteristics interact with policy interconnections, diverse stakeholders - from research funders to procurement agencies - can make more informed decisions that balance scientific opportunity with policy feasibility. This produces more resilient innovation ecosystems with higher probability of translating scientific advances into population health benefit.

Strategic Implications and Implementation Pathways

The Policy-Driven Health System Framework has significant implications for diverse stakeholders. Health technology companies must evolve from viewing policy as an external constraint to recognizing it as foundational architecture requiring strategic engagement. Health systems must move from fragmented policy development within silos to integrated policy architecture spanning interconnections. Policymakers must do more to anticipate the unintended consequences of their isolated policy changes, so that changes in one domain do not create negative ripple effects requiring coordinated policy evolution.

Implications for Health Technology Companies

For health technology companies, the framework highlights the need to move beyond treating policy as an external constraint and instead engage with it as a strategic determinant of access and value realization. This requires investment in policy intelligence capabilities comparable to market research and competitive intelligence functions.

Key capabilities include systematic monitoring of policy evolution across markets, analysis of policy interconnections affecting portfolio value, structured stakeholder mapping, and scenario planning under conditions of policy uncertainty. Engagement strategies should be tailored to how evidence, financing, governance, and implementation decisions interact within specific system contexts.

Evidence generation strategies must also evolve. Clinical development and real-world evidence plans should be explicitly aligned with the value demonstration–financing interconnection, ensuring that trials and post-market studies generate evidence that is relevant not only for regulatory approval, but for reimbursement, budgeting, and implementation decisions that ultimately determine uptake.

Implications for Health Systems and Policymakers

For health systems and policymakers, the framework emphasizes the limitations of siloed policy development and the need to institutionalize policy architecture thinking within planning and reform processes. This requires durable coordination mechanisms across traditionally separate domains, including research and innovation policy, regulatory policy, financing and reimbursement policy, and implementation and delivery policy.

Policy reforms should be assessed for their implications across all five interconnections prior to implementation, rather than evaluated solely within the domain they directly target. Strengthening ex ante impact assessment, cross-ministerial coordination, and adaptive policy adjustment mechanisms is critical to anticipating system-wide effects and avoiding unintended consequences that undermine access or create implementation gaps.

Implications for Multilateral Organizations

For multilateral organizations, the findings suggest a need to reorient country support toward policy architecture assessment and strengthening, rather than focusing primarily on isolated technical interventions. Technical assistance should prioritize interconnection policies where gaps span multiple domains and where misalignment is most likely to constrain system performance.

Financing mechanisms can play a catalytic role by incentivizing integrated reform packages that address governance, financing, and implementation interfaces simultaneously. By supporting coherent policy architecture rather than discrete policy components, multilateral actors can enhance the sustainability and impact of country-level investments.

Conclusion: Policy as Health System Architecture

The Policy-Driven Health System Framework fundamentally reframes policy’s role in health systems. Policy is not merely a set of rules to navigate or barriers to overcome - it is the architecture determining how health system components interact, coordinate, and create value. Just as building architecture shapes how people move through physical spaces, policy architecture determines how innovation connects to investment, value demonstration informs financing, financing relates to governance, and governance translates into patient access.

Policy cannot be treated as an afterthought in innovation strategy, investment decisions, value assessment, financing reform, or implementation planning. Health systems are complex and adaptive, and this framework extends that insight by identifying the specific policy mechanisms required at five critical interconnections. These interconnections represent where policy architecture is most essential and where its absence is most damaging.

For health technology companies, policy architecture understanding creates competitive advantage through proactive positioning, evidence alignment, and portfolio optimization. For health systems and policymakers facing technological acceleration, demographic transitions, and fiscal constraints, policy architecture provides a mechanism capable of aligning diverse actors toward coherent objectives. Health systems with strong policy architecture are more likely to demonstrate superior performance, greater resilience, and more equitable outcomes.

The transition from fragmented policies to integrated policy architecture requires deliberate work: analyzing current interconnections, identifying gaps, designing bridging policies, implementing reforms, and maintaining architecture as contexts evolve. This framework provides a structured approach, enabling stakeholders to shift from reactive policy navigation to proactive engagement with policy architecture. Health system performance ultimately depends not on sophistication of individual components but on quality of integration across them. That integration requires considered policy architecture.

References

- Montenegro H, Holder R, Ramagem C, Urrutia S, Fabrega R, et al. (2011) Combating health care fragmentation through integrated health service delivery networks in the Americas: lessons learned. Journal of Integrated Care 19(5): 5-16.

- Kern LM, Bynum JPW, Pincus HA (2024) Care Fragmentation, Care Continuity, and Care Coordination How They Differ and Why It Matters. JAMA Internal Medicine 184(3): 236-237.

- Lal A, Erondu NA, Heymann DL, Gitahi G, Yates R (2021) Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. The Lancet 397(10268): 61-67.

- Spicer N, Agyepong I, Ottersen T, Jahn A, Ooms G (2020) ‘It’s far too complicated’: why fragmentation persists in global health. Globalization and Health 16(1): 1-13.

- WHO (2009) Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening Pp: 4-112.

- Adam T, De Savigny D (2012) Systems thinking for strengthening health systems in LMICs: need for a paradigm shift. Health Policy and Planning 27(suppl_4): 1-3.

- Saltman RB, Ferroussier Davis O (2000) The concept of stewardship in health policy. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78(6): 732-739.

- Greer SL, Wismar M, Figueras J (2016) Strengthening health system governance. Better policies, stronger performance. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Series 1: 1-290.

- Health in all policies: Helsinki statement, framework for country action (2014).

- What you need to know about Health in All Policies Pp: 1-4.

- WHO (2014). Health in All Policies (HiAP) Framework for Country Action Pp: 1-17.

- Atun R, Knaul FM, Akachi Y, Frenk J (2012) Innovative financing for health: What is truly innovative? The Lancet 380(9858): 2044-2049.

- Joore M, Grimm S, Boonen A, De Wit M, Guillemin F, et al. (2020) Health technology assessment: a framework. RMD Open 6(3): 1-3.

- Wenzl M, Chapman S (2019) Performance-based managed entry agreements for new medicines in OECD countries and EU member states: How they work and possible improvements going forward. OECD Health Working Papers 115(115): 1-98.

- Gamba S, Pertile P, Vogler S (2020) The impact of managed entry agreements on pharmaceutical prices. Health Economics 29(S1): 47-62.

- Mundy L, Forrest B, Huang LY, Maddern G (2024) Health technology assessment and innovation: here to help or hinder? International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 40(1): 1-7.

- Thokala P, Duenas A (2012) Multiple criteria decision analysis for health technology assessment. Value in Health 15(8): 1172-1181.