Exploring the Role of Indigenous Knowledge

in Alleviating the Financial Challenges Facing

African Indigenous Churches in Zimbabwe: A

Case Study of Harare Metropolitan

Gerald Munyoro1*, Wiseman Mulauzi2 and Moses Cyrial Ngawaite Chihobvu3

1ZOU Graduate School of Business, Faculty of Commerce, Zimbabwe Open University, Harare, Zimbabwe.

2UZ Business School, Faculty of Business Management Sciences & Economics, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe.

3CUT Graduate Business School, School of Entrepreneurship & Business Sciences, Chinhoyi University of Technology, Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe

Submission: November 13, 2025;Published: December 09, 2025

*Corresponding author: Gerald Munyoro, ZOU Graduate School of Business, Faculty of Commerce, Zimbabwe Open University, Harare, Zimbabwe.

How to cite this article: Gerald M,Wiseman M, Moses Cyrial Ngawaite C. Exploring the Role of Indigenous Knowledge in Alleviating the Financial Challenges Facing African Indigenous Churches in Zimbabwe: A Case Study of Harare Metropolitan. Juniper Online Journal of Public Health, 10(3). 555788.DOI: 10.19080/JOJPH.2025.10.555788.

Abstract

This study investigates the potential of Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) as a strategic resource for enhancing the financial sustainability of African Indigenous Churches (AICs) in Zimbabwe. Employing a qualitative research design, the study draws on in-depth interviews with church leaders, congregants, and community-based knowledge holders, complemented by document analysis. The research identifies the key financial challenges confronting AICs and critically examines how indigenous economic practices can provide culturally grounded, sustainable alternatives to conventional funding models. The findings indicate that several indigenous economic mechanisms such as communal labour systems (nhimbe), local savings and credit schemes (rounds), traditional fundraising through culturally significant events, and the utilisation of indigenous resources including herbal medicine, crafts, and land-based knowledge which remain largely underutilised within AICs. These practices, deeply embedded in principles of reciprocity, collective responsibility, and community solidarity, offer substantial opportunities to strengthen the financial capacity and resilience of churches. However, the study also reveals multiple barriers that limit the effective integration of IKS into church financial strategies. These include institutional inertia, theological reservations, restrictive regulatory frameworks, and evolving social dynamics that challenge the relevance and application of indigenous practices in contemporary church contexts. Such constraints have contributed to the marginalisation of IKS despite their proven economic and social value within local communities. The study concludes by offering practical recommendations for church leadership and policymakers aimed at bridging these gaps. It advocates for the deliberate and strategic incorporation of Indigenous Knowledge Systems into church financial planning and governance structures. By doing so, AICs can foster long-term financial sustainability, enhance institutional resilience, and reaffirm their cultural and social relevance within their communities.

Keywords:Indigenous Knowledge Systems; African Indigenous Churches; Financial Sustainability; Harare Metropolitan; Communal Reciprocity; Local Economy, Church Economics

Abbreviations: IKS: Indigenous Knowledge Systems; AICs: African Indigenous Churches; TEK: Traditional Ecological Knowledge; FGDs: Focus Group Discussions; NGOs: Non-Governmental Organizations

Introduction

Zimbabwe continues to grapple with persistent economic challenges, including high inflation, currency devaluation, widespread unemployment, and inconsistent availability of foreign currency. These issues permeate all sectors of society, including religious institutions. African Indigenous Churches (AICs), in particular, are significantly affected due to their heavy reliance on members’ contributions through offerings, donations during special events, and, at times, support from external sources [1,2]. As a result, many of these churches face severe operational difficulties [2,3].

Historically, numerous churches in developing countries like Zimbabwe have maintained relationships with Western counterparts and in the process receiving financial and material support through sister churches and faith-based non-governmental organizations [4,5]. However, this traditional funding from Western donors has been steadily declining, further weakening church operations. This funding gap has widened at a time when members’ incomes are increasingly insufficient to meet their own needs and let alone support the church [2,6,7].

Regrettably, there is a noticeable lack of scholarly inquiry into whether entrepreneurship could provide a viable solution to the financial constraints faced by churches in Zimbabwe and beyond. Few researchers have ventured into the relatively unexplored domain of entrepreneurship within religious institutions [7] with the notable exception of a study by Munyoro and Ncube (2020). This lack of attention is surprising, considering that religion and particularly Christianity plays a central role in the daily lives of many people worldwide, offering moral and ethical frameworks that guide behaviour [2,7,8].

Furthermore, church gatherings provide fertile ground for networking among congregants. Therefore, these interactions, which occur after services or during significant social events like funerals and weddings, often extend beyond spiritual concerns to include discussions on business and economic matters [7,9]. In addition, many churchgoers also seek divine intervention for economic breakthrough and prosperity. Despite this, entrepreneurship particularly, forms rooted in Indigenous Knowledge Systems, remains largely absent from church discourse [2,7,8,10].

Therefore, it is against this backdrop, this study seeks to explore the potential role of Indigenous Knowledge in addressing the financial challenges confronting African Indigenous Churches in Zimbabwe. Thus, by integrating traditional wisdom and entrepreneurial practices, AICs may uncover sustainable solutions to their financial woes while remaining true to their spiritual and cultural foundations.

Problem Statement

Zimbabwe’s persistent economic instability which is characterised by high inflation, currency devaluation, unemployment, and limited access to foreign currency has deeply impacted all sectors of society, including religious institutions such as African Indigenous Churches (AICs), [1,2]. which largely depend on member contributions and dwindling external support to sustain their operations [2,3]. This financial vulnerability has intensified as traditional funding avenues [11,5], especially from Western donors and sister churches, continue to decline, leaving AICs struggling to meet operational demands amidst widespread poverty among congregants [2,6,7].

Despite the critical role churches play in Zimbabwean society, both spiritually and socially unfortunately, there remains a significant gap in scholarly inquiry into alternative, sustainable financial strategies, particularly the potential of entrepreneurship rooted in Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) [7]. While congregational gatherings often foster discussions beyond spiritual matters, including economic aspirations and business networking, the formal incorporation of entrepreneurship within church structures remains largely unexplored [2,12]. This study therefore seeks to address this oversight by investigating how Indigenous Knowledge can inform entrepreneurial initiatives within AICs, offering contextually grounded, sustainable solutions to their financial challenges while preserving their spiritual and cultural identity. In addition, the study will aim to explore how Indigenous Knowledge (IK) might offer alternative or supplementary economic practices for AICs in Zimbabwe focusing on Harare as well as what forms these take in practice, and what impediments exist.

Literature Review

The Origins and Growth of Christianity

Christianity originated in the first century CE as a sect within Second Temple Judaism in Roman-ruled Judea [2,13,14]. Its rapid expansion was propelled by the apostles of Jesus, who despite facing persecution, spread the message throughout Syria, Europe, Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Transcaucasia, Egypt, and Ethiopia [14]. As increasing numbers of gentiles converted, Christianity began to diverge from Jewish customs [13]. The destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70 marked a significant turning point: Judaism became more decentralized, while Christianity gained traction as a distinct religion [2,13,14].

In Africa, Christianity was established as early as the second century in Alexandria, Egypt. However, much of the early North African Church was later diminished by Islamic conquests [15-17]. In contrast, Christianity in Southern Africa expanded alongside colonialism and is now the continent’s fastest-growing religion by numbers [18,19]. It is particularly flourishing in East and Southern African nations such as Uganda, Kenya, Zambia, and Zimbabwe [2]. This growth is largely attributed to the moral authority of faith leaders and the strong ethical foundations of religious institutions particularly in Zimbabwe [19,20].

What is Christianity?

Christianity is a monotheistic, Abrahamic religion cantered on the life, teachings, and miracles of Jesus of Nazareth, who is regarded as the Son of God [14,21,22]. According to Christian belief, Jesus was crucified and resurrected for the salvation of humankind [14,21,22]. Globally, Christianity has over 2.4 billion adherents, making it the largest religion in the world [Woodhead 2004, 2]. In this study, the terms Christianity and the Church are used interchangeably to refer either to the collective body of believers or to the physical spaces where worship occurs [Roberts 2011, Mark 2021]. Paradoxically, Christianity promotes humility while simultaneously shaping social justice movements and wielding influence through worldly power even revering a crucified Messiah while participating in global institutions of authority [Woodhead 2004, 2].

Defining the Church

The term Church refers to the global Christian community or to specific congregations of believers [23]. It derives from the Greek word ekklesia, originally meaning “assembly,” which in the New Testament evolves to describe both local gatherings and the universal body of Christians [24-26].

The Role of Christianity in Africa

Christianity has played a transformative role in Africa’s development. It introduced systems of education and healthcare, contributed to peacebuilding, promoted food security, combated HIV/AIDS, and empowered civil society [27,28, Hays et al. 2020]. Its message of hope and compassion has had significant spiritual, social, and physical impacts on African communities [2,29].

Challenges Facing Christianity Today

Despite its positive contributions, Christianity faces a range of internal and external challenges and these include intra-church conflicts driven by politics, ethnicity, and leadership disputes as well as Christian-Muslim tensions related to doctrine and conversion, public health crises such as malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis, socio-political instability, poverty and limited access to education [20,30]. Additionally, controversial issues such as the ordination of gay clergy, abortion, women’s leadership, and evolving worship styles continue to spark debate. Financially, many churches face hardship as Western donor support declines [6]. As traditional denominations struggle, Pentecostal and evangelical movements attract large followings with dynamic worship and direct messaging [10,31]. African Indigenous Churches (AICs) in particular face acute financial challenges, prompting increasing interest in leveraging Indigenous Knowledge (IK) for sustainable development.

Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge (IK/TK)

Traditional Knowledge (TK) refers to long-established, culturally embedded knowledge systems developed by indigenous communities through sustained interaction with the natural environment. It encompasses diverse domains such as agriculture, medicine, navigation, climate interpretation, spiritual practices, and resource management [32,33]. Unlike Western science, which is empirical, analytical, and compartmentalized, TK is holistic, spiritual, and typically transmitted orally [34]. It enables communities to adapt to environmental changes, maintain biodiversity, manage natural resources sustainably, interpret climatic conditions, treat illnesses, and pass down moral values, taboos, and conservation ethics. Therefore, TK represents more than knowledge as it constitutes identity, survival, and cultural heritage.

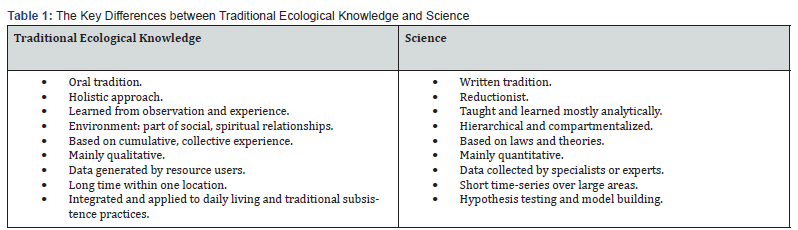

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is a subset of Indigenous Knowledge that focuses specifically on the relationship between living beings and their environments. It evolves through experiential learning, storytelling, and ritual practices [35]. Pioneers such as Harold Conklin revealed the ecological sophistication of indigenous communities, particularly in resource management [36,37]. By the mid-1980s, TEK gained global recognition for its relevance to sustainable development. The 1987 Brundtland Report underscored its importance in ecosystem management and in addressing contemporary environmental challenges [38]. Table 1

Source: Mazzocchi (2006) and Houde (2007)

Aspects of Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Houde (2007) identifies six core dimensions of TEK and that is Empirical Knowledge-Observation and is based on understanding of species, behaviours, and ecosystems, whilst, Resource Management-Ethical is a sustainable use of nature through indigenous practices and Historical Use-Oral is histories of land use, sacred sites, and settlement, whereas Ethics & Values-Spiritual and moral codes do guide human-environment interaction and Culture & Identity-Language, stories, and traditions shape the community and place whereas, Cosmology-Worldviews explain how nature and humans are interconnected.

Research Methodology

This study adopted a qualitative case study design, which was appropriate for exploring complex phenomena within their reallife context [39,40]. In fact, the focus was on African Indigenous Churches (AICs) in Harare Metropolitan and the study was examining how AICs can navigate financial stress through the use of Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS). Thus, a case study approach allowed for an in-depth, holistic investigation of the socio-cultural, spiritual, and economic dimensions influencing AICs [39,41].

Consequently, qualitative methods enabled the researchers to interpret the meanings participants assign to their experiences, behaviours, and worldviews [21,42]. In this study, the research encompassing both urban and peri-urban communities and these suburbs presented a diverse context where various socioeconomic dynamics intersect with traditional religious practices. Thus, it hosts a significant representation of AICs, including well-established denominations as well as smaller and emerging congregations. Accordingly, the dual urban–peri-urban focus allows for an examination of how spatial location influences both financial resilience and the utilisation of IKS in church settings [43].

The study employed purposeful sampling to select information-rich cases relevant to the research questions [39,44]. Consequently, the participant group included Church leaders like bishops, pastors, elders and custodians of spiritual and administrative matters within the church. In addition, there were congregants such as lay members who actively participate in church life, traditional knowledge-holders like individuals within or associated with the church who maintain cultural and indigenous economic practices as well as community economists and resource users such as members involved in livelihood activities influenced by indigenous or faith-based economic practices such as communal savings, barter trade and informal economies. Thus, inclusion of diverse perspectives ensured a holistic understanding of how AICs respond to financial stress and engage with IKS [21,39].

In this study, a multi-method data collection strategy will be employed, consistent with qualitative case study protocols [45]. Thus, in-depth interviews were conducted with church leaders, congregants, and traditional knowledge-holders as noted above. This method allowed flexibility in probing participants’ experiences, while maintaining a focus on key thematic areas such as financial stressors, coping strategies, and indigenous economic practices [45,46]. Additionally, Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), with congregants and community members was employed to gather collective views and explore shared practices around economic resilience because FGDs are exclusively useful in growing communal values and uncovering group-based IKS mechanisms [47]. Furthermore, observations were carried out during church gatherings, prayer meetings, and other relevant events where indigenous practices are enacted such as traditional healing and communal resource sharing. In this case, the researcher adopted an overt participant observer role in order to ensure ethical transparency [46,47]. For the areas which were accessible, the study examined church financial records, policy documents, minutes of meetings, and pastoral communications in order to triangulate interview and observation data. Thus, these documents provided insights into the administrative and economic frameworks operating within the churches [47,48].

In this study, data was analysed using thematic analysis, which is suitable for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within qualitative data [46,47,49]. Thus, the process involved transcribing interviews and FGD recordings, initial coding of textual data, grouping codes into broader themes such as financial stressors, indigenous coping mechanisms, barriers or enablers to financial sustainability, and policy/practice recommendations as well as cross-verification of themes through comparison with observation notes and document analysis [46,47,50]. In addition, NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software was used in order to assist in data management and coding [21,46,47].

In this study, ethical clearance was sought from recognised and relevant authorities and the study adhered to the following ethical principles such as informed consent which encourages researchers to inform participants about the study’s purpose, procedures, and their rights and including the right to withdraw at any time before participation and for the researchers to inform the participants about confidentiality and anonymity, in which pseudonyms are used in reporting, and any identifiable information in order to ensure that names are securely stored and protected [21,46,51]. It is also important for the researchers to be aware of the cultural and religious sensitivity when conducting data and hence, particular care should be taken to respect indigenous spiritual practices and beliefs. Thus, in this study, the researchers’ positionality was reflexively considered in order to minimise imposition of external worldviews [21,51,52].

Findings

Financial Challenges Facing AICs in Harare

The study reveals that African Indigenous Churches (AICs) in Zimbabwe tend to rely heavily on tithes and offerings, which are inherently unpredictable and especially during times of economic crisis. In addition, inflation continues to erode the value of both savings and offerings, further exacerbating financial instability. Furthermore, accessing foreign currency has also become increasingly difficult, limiting the ability to import essential items such as building materials and equipment like public address systems. Moreover, the prevailing economic conditions have significantly delayed church projects due to rising operational costs, including utilities, transport, and maintenance. The study also highlights that AICs are suffering from a lack of financial reserves and diversified income streams and this has led to pastors and church workers being frequently underpaid or not paid at all and ultimately compromising their welfare and resulting in churches struggling to achieve their development goals [53-58].

Existence & Value of Indigenous Knowledge

The study shows that indigenous knowledge is deeply ingrained in the daily lives of Zimbabweans and, by extension, in AICs. Far from being purely cultural, this knowledge encompasses economic survival strategies, indigenous entrepreneurship models, and communal resource management. However, some congregants perceive entrepreneurial initiatives based on indigenous knowledge as low-status activities, resulting in diminished participation and support congregants.

Indigenous Economic Practices / Indigenous Knowledge with Potential

The research also reveals a decline in communal labour and mutual support. Traditionally, congregants voluntarily contributed materials and labour for church construction and maintenance and an aspect that has significantly dwindled in recent times. AICs have historically relied on local savings and rotating credit systems similar to stokvels or mukweretesi, were members pool resources and rotate fund distributions. However, these practices are becoming increasingly difficult to sustain due to the challenging economic environment. In addition, AICs utilize traditional crafts, herbal resources, and land-based enterprises as alternative support systems. These include where doctrinally acceptable, small-scale herbal medicine, the production of handmade crafts, weaving, and pottery. If land is available, churches often apply indigenous agricultural methods to grow food for internal use or for sale. Cultural events such as traditional festivals, thanksgiving ceremonies, and harvest celebrations are also used as platforms for fundraising and community engagement. The study also notes the role of traditional norms of reciprocity, where members share resources and provide support in times of need, thereby fostering communal trust and long-term sustainability [59-63].

Barriers to Leveraging IKS in Church Finance

The study identifies several barriers to fully integrating IKS into church financial systems such as theological resistance and in this case some church leaders view indigenous practices as incompatible with Christian doctrine, raising concerns over syncretism; regulatory and legal constraints and these include permits, taxation, licensing of enterprises, and regulations on health, safety, and land use, factors that hinder entrepreneurial activities; skills and capacity gaps because many church leaders lack essential skills such as financial management, marketing, documentation, and general business acumen which are essential in managing entrepreneurial projects; perception and prestige, which include activities like craft-making or farming and are often viewed as low-status and discourages involvement from congregants; economic instability and which focuses on high inflation and currency volatility and these normally pose serious risks to long-term financial planning and the success of entrepreneurial projects and limited access to capital and most AICs lack tangible assets or acceptable collateral in order to secure loans. Even when credit is available, members are often reluctant to use church property as security due to a cultural disconnect from entrepreneurial thinking [64-67].

Underutilization of Indigenous Knowledge

It is worth noting that despite the richness of indigenous knowledge systems, many AICs continue to depend on foreign donations from Western countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States. This dependency has led to the marginalisation of local knowledge, which is often dismissed as unscientific, superstitious, or primitive. This perspective persists largely due to the lingering influence of colonial and missionary ideologies.

Association between IK, Religion & Entrepreneurship

The study establishes a strong link that exists between religion in AICs, indigenous knowledge, and entrepreneurship. In fact, indigenous knowledge holds great potential for initiating sustainable income-generating projects, including agriculture, herbal medicine, craft production, and cooperative businesses. Thus, when properly harnessed, this knowledge can offer churches viable paths toward financial independence and community empowerment.

Discussion

It is worth noting that indigenous knowledge practices offer contextual resilience to AICs because they are locally embedded, culturally accepted, rely less on external capital but more on both human and social capital. In addition, there is synergy between IKS and church mission around diakonia and community service. For example, land‐based agricultural schemes both provide income and food for vulnerable members. Furthermore, the case of churches expanding into business or income generating projects like those documented in studies of classical Pentecostal churches suggests a model which might be adapted in AICs using IKS. Likewise, the risk is that if indigenous knowledge is commodified badly or without community input, it loses its meaning or is resisted.

Theoretical Implications

This study challenges the dominance of Western-centric development models in Zimbabwe’s religious and economic spheres. It advocates for the decolonization of theology and economics by promoting local solutions and homegrown innovation. The findings suggest that, when properly empowered, faith-based institutions can serve as key economic drivers through the use of indigenous models.

Recommendations

The study highlights the need for African Indigenous Churches (AICs) to adopt comprehensive strategic development frameworks that explicitly incorporate indigenous economic practices. Thus, these frameworks should be integrated into the churches’ strategic planning processes, including budget forecasting and income diversification strategies. Furthermore, the study emphasises the importance of training and capacity building and this can be achieved by equipping church leaders and congregants with essential business skills such as financial management and entrepreneurship. Such efforts therefore, may be supported through partnerships with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and government institutions. In addition, there is a need for policy and regulatory support tailored to the context of AICs. Therefore, government, in collaboration with church denominations, should implement tax regulations that provide incentives for small enterprises operating within AICs. These incentives could include tax exemptions or reductions for ventures in crafts, agriculture, and herbal medicine especially during their formative stages in order to reduce financial burdens and encourage growth. The study also calls for theological reflection among church leaders, facilitated through dialogue, to discern which indigenous practices are theologically appropriate and culturally acceptable.

As vital actors in community development, AICs must involve congregants in identifying relevant and feasible indigenous knowledge practices. This participatory approach ensures community ownership and enhances the legitimacy of development initiatives. Thus, given that entrepreneurial ideas have life cycles, the study recommends initiating small-scale pilot projects and these pilots, based on Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS), could include herbal gardens, craft workshops, and communal agriculture. Consequently, profits generated from such enterprises should support church welfare and infrastructure development. It is worth noting that strategic partnerships are also vital. Accordingly, AICs are encouraged to collaborate with academic institutions such as the University of Zimbabwe, NGOs, and government agencies in order to access funding, technical expertise, and market opportunities for indigenous products, including crafts and herbal remedies.

Moreover, the government should allocate land to AICs for agricultural and entrepreneurial projects rooted in indigenous knowledge and therefore, support should also be extended to educational reforms aimed at improving the financial literacy and formal education of church leaders, including pastors and archbishops, in order to prevent mismanagement of funds of entrepreneurial projects that they would have embarked on. To align with Zimbabwe’s Vision 2030 and the Education 5.0 model, the government should support the establishment of church-led innovation initiatives such as Innovation Hubs. Thus, Indigenous Knowledge (IK) and AICs should be mainstreamed into national economic planning, particularly in roles that contribute to spiritual and moral nation-building.

Conclusion

The financial challenges facing African Indigenous Churches AICs in Zimbabwe are intense and multi‐dimensional. However, indigenous knowledge systems present an underutilised yet valuable resource for building resilience and promoting sustainability. Thus, by harnessing communal reciprocity, local resources, traditional fundraising methods, and culturally embedded practices, AICs have the potential to develop more predictable and diversified income streams. Accordingly, the path to success for AICs lies in addressing and overcoming institutional, theological, and regulatory barriers. Therefore, by adopting a strategy that integrates faith, culture, and the local economy, AICs can transition toward more sustainable models of mission and service and particularly important in Zimbabwe’s volatile economic environment. It is then worth noting that both Christianity and indigenous knowledge systems have played a foundational role in shaping African society. AICs, therefore, are not only spiritually and socially significant but also hold economic potential as agents of economic development.

Therefore, to unlock this potential, AICs should begin to integrate the practical sustainability offered by indigenous knowledge into their structures and operations. This approach fosters a collaborative relationship between faith and traditional wisdom, enabling the creation of resilient and self-sustaining communities that contribute to lasting socio-economic stability in Zimbabwe. In conclusion, this study argues for the urgent need for African Indigenous Churches to reclaim indigenous knowledge as a viable pathway to financial sustainability. Thus, this involves shifting away from dependence on Western aid and embracing a development model that is culturally resonant, economically sound, and spiritually aligned with the values of the communities it seeks to serve.

References

- Okwueze D, Ononogbu P (2010) Understanding and managing public organizations (4th) San Francisco, CA.

- Munyoro G, Ncube P (2020) The role of entrepreneurship in sustaining churches’ operations in Zimbabwe: A case study of Bulawayo Metropolitan’. Journal of Business Administration and Management Sciences Research 8(1): 1-25.

- Desmond H (2016) Reflections on a missional ecclesiology for Africa’s expressions of Christianity through the Tswana lens: Verbum et Ecclesia 37: 1-8.

- Musoni (2013) Studies on AICs and socio-economic dynamics.

- Mahiya IT, Murisi R (2021) Reconfiguration and adaptation of a church in times of Covid-19 pandemic: A focus on selected churches in Harare and Marondera, Zimbabwe. Cogent Arts & Humanities 9(1): 1-16.

- Watkins SC, Swidler A (2013) Working misunderstandings: Donors, brokers, and villagers in Africa’s AIDS industry. Population and Development Review 39(3): 495-515.

- Tengeh RK (2016) Entrepreneurial resilience: the case of Somali grocery shop owners in a South African township.

- Geertz C (1993) The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. Basic Books New York.

- Munyoro G, Dewhurst JHL (2010) The significance of identifying industrial clusters: the case of Scotland.

- Togarasei L (2016) Historicising Penteoostal Christianity in Zimbabwe. Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 42(1): 1-13.

- Musoni P (2013) African Pentecostalism and sustainable development: A study on the Zimbabwe assemblies of God Africa, forward in faith church. International Journal of Humanities and social science invention 2(10): 75-82.

- Munyoro G, Chikombingo M, Nyandoro Z (2016) 'The Motives of Zimbabwean Entrepreneurs: A Case Study of Harare.' Africa Development and Resources Research Institute Journal, Ghana 25 7(3).

- Kammer FSJ (2004) An Introduction to Catholic Social Thought, published by Paulist Press.

- Kimbrough N (2005) A macroeconomic policy framework for economic stabilization in Zimbabwe. In: Hany Besida, ed. Zimbabwe: picking up the pieces. New York: Palgrave Macmillan Pp: 83-105.

- Hugh BA (2004) Traditional leadership in South Africa: a critical evaluation of the constitutional recognition of customary law and traditional leadership (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Western Cape).

- Bunson R (2015) How entrepreneurial firms can benefit from alliances with large partners. Academy of Management Executive 15(1): 139-148.

- Agbaw Ebai MA, Levering M (2021) Joseph Ratzinger and the Future of African Theology. Wipf and Stock Publishers.

- Heimlich P (2010) The synergistic effect of market orientation and learning orientation on organizational performance. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science 27(4): 411-427.

- Mauro JC (2018) Decoding the glass genome. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science 22(2): 58-64.

- Corman P (2015) How to measure an organization’s learning ability: The facilitating factors-Part II. Journal of Workplace Learning 10(1) Ardichvili.

- Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhill A (2019) Research methods for business students (8th ed). Pearson Education.

- Jaroslav M (2022) The Impact of Working Capital Management on Corporate Performance in Small-Medium Enterprises in the Visegrad Group: MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

- Diaz Pabon V (2018) Mixed Methods Sampling: A Typology with Examples, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, SAGE.

- Matthew 16:18; “And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock, I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it.”

- Acts 5:11; "Great fear seized the whole church and all who heard about these events."

- Romans 16:5 "Greet also the church that meets at their house."

- Mbiti J (1978) The future of Christianity in Africa. Cross Currents 28(4): 387-394.

- Akinleye SO, Awoniyi SM, Fapojuwo OE (2005) Evaluation of the National Fadama Development Project Approach to Rural Development: Lessons for Local Government Councils in Nigeria. Farm Management Association of Nigeria (FAMAN) Conference.

- Chidarikire P (2012) The sustainability of the entrepreneurial orientation-performance relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 24(1): 37-48.

- Nelson JL (2021) Imagined audiences: How journalists perceive and pursue the public. Journalism and Pol Commun Unbo.

- Powlison D (2017) How Does Sanctification Work? Crossway Books.

- Berkes F (1988) Subsistence fishing in Canada: a note on terminology. Arctic 41(4): 319-320.

- Houde N (2007) The six faces of traditional ecological knowledge: challenges and opportunities for Canadian co-management arrangements. Ecology and Society 12(2).

- Mazzocchi F (2006) Western science and traditional knowledge: Despite their variations, different forms of knowledge can learn from each other. EMBO reports 7(5): 463-466.

- Berkes F (1993) Traditional ecological knowledge in perspective. Traditional ecological knowledge: Concepts and cases 1: 1-9.

- Freeman LC (1992) The sociological concept of" group": An empirical test of two models. American journal of sociology 98(1): 152-166.

- Becker CD, Ghimire K (2003) Synergy between traditional ecological knowledge and conservation science supports forest preservation in Ecuador. Conservation Ecology 8(1): 1

- World Commission on Environment and Development (1987) Brundtland Report which underscored the importance of environment in its ecosystem management and in addressing contemporary environmental challenges.

- Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2018) Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Yin RK (2018) Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage.

- Stake RE (1995) The art of case study research. Sage.

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (2023) The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (6th ed.). SAGE.

- Chitando E (2020) African Initiated Churches and the quest for community development in Zimbabwe. Harare: University of Zimbabwe Publications.

- Patton MQ (2015) Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). Sage.

- Creswell JW, Poth CN (2023) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (5th ed.). SAGE.

- Munyoro G (2014) Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Handouts in Enhancing Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Africa Development and Resources Research Institute 6(2): 95-107.

- Krueger RA, Casey MA (2021) Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research (6th ed.). SAGE.

- Bourdillon MFC (1982) The Shona peoples: An ethnography of the contemporary Shona, with special reference to their religion. Mambo Press. Bowen GA (2009) Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal 9(2): 27-40.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77-101.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2021) Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. SAGE.

- Taherdoost H, Madanchian M (2025) The impact of survey response rates on research validity and reliability. In Design and Validation of Research Tools and Methodologies. IGI Global.

- Smith LT (2021) Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (3rd ed.). Zed Books.

- Bekithemba D, Mufanechiya A, Mufanechiya T (2015) Religious Studies and Indigenous Knowledge in Secondary Schools in Zimbabwe: Bubi District Case Study. The Journal of Pan African Studies 8(8).

- Chandy L, Kharas H (2014) What do new price data mean for the goal of ending extreme poverty? Brookings Institution.

- Chitando E, Tarusarira J (2021) Religions in Africa in the 21st Century. Routledge.

- Hulme D (2015) Global poverty: Global governance and poor people in the post-2015 era. Routledge.

- Humbe BP (2022) African Initiated Churches providing prophetic direction for women savings clubs: The case of Masvingo, Zimbabwe. HTS Teologiese Studies

- Mbiti JS (1991) Introduction to African Religion, 2nd. Nairobi: EAEP.

- Munyoro G, Gumisiro C (2017) The Significance of Entrepreneurial Culture in the Security Sector: A Case Study of Zimbabwe Prisons and Correctional Service: IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Business Management 5(5): 15-28.

- Ncube, Chigwada, Ngulube, Maluleka (2025) Government support for indigenous knowledge for sustainability in Southern Africa: SA J Info Management 27(1).

- Pedzisai C (2020) An analysis of indigenous agricultural knowledge systems in the Zimbabwe secondary school agriculture curriculum: prospects and opportunities. (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of South Africa.

- Shumba T (2014) Donor funding not sustainable. The Herald.

- Smith LT (2012) Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

- Tagwirei K (2022) “Beyond tithes and offerings: Revolutionising the economics of Pentecostal churches in Zimbabwe.” HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 78(4).

- Tagwirei K, Masango M (2023) Rethinking the identity and economic sustainability of the church: Case of AOG BTG in Zimbabwe. HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 79(2).

- Stake RE (2005) Qualitative Case Studies. In Denzin & Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. SAGE.

- World Bank (2023) Poverty overview. World Bank.