Background

The examination of family planning and reproductive policies within colonial governance structures reveals fundamental tensions between metropolitan control and local health autonomy. Puerto Rico’s experience from 1969 to 1980 provides a case study of how population control programs functioned as instruments of colonial management rather than responses to community-identified health needs. This analysis situates Puerto Rico’s family planning policies within the broader context of U.S. development agendas and demographic anxieties that characterized the post-1960s era.

Puerto Rico’s political status as an unincorporated territory of the United States, formalized through the establishment of the Estado Libre Asociado (Free Associated State) in 1952, created a unique framework for the implementation of federal health policies [1]. This ambiguous political relationship neither fully independent nor incorporated as a state established conditions where health policy decisions were initiated with metropolitan priorities in mind rather than local democratic processes. The island’s economy had undergone dramatic transformation under U.S. control, shifting from an agricultural base where large families constituted economic assets to an industrialized system where family size became increasingly viewed through the lens of economic burden [2].

The theoretical framework of dependency theory illuminates how economic and political subordination shaped health policy formation in Puerto Rico. The colonial relationship created structural conditions where the nation with economic and political power set the pace for social, economic, and political development of the dependent territory [3]. This pattern of dependency manifested clearly in health policy, where funding mechanisms, program priorities, and implementation strategies reflected U.S. concerns about overpopulation, migration to the mainland, and economic development rather than locally determined health needs.

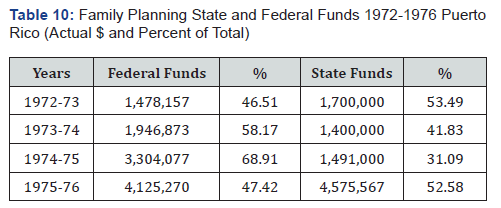

Historical institutionalism provides additional analytical leverage for understanding how colonial structures became embedded in health governance systems. The requirement for Puerto Rico to match federal funding at the highest possible rate despite having a per capita income less than half of Mississippi’s, the poorest U.S. state exemplified how institutional arrangements reinforced dependency while limiting local policy autonomy [4]. These matching requirements meant that by 1975-76, Puerto Rico committed 4.2% of its total health budget to family planning programs, constraining resources available for other health priorities.

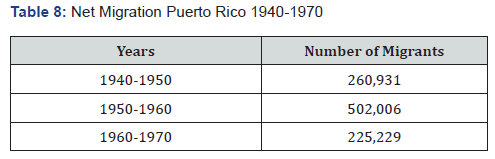

The emergence of U.S. population control concerns in the 1960s coincided with anxieties about Puerto Rican migration to the mainland. Federal policymakers increasingly viewed Puerto Rico’s population growth as a threat requiring intervention [5]. Between 1940 and 1970, net outmigration from Puerto Rico totaled nearly one million people, yet unemployment remained persistently high, reaching 12.0% in 1973 and 17.5% in 1980 [6]. This demographic context provided justification for aggressive family planning interventions that went beyond voluntary reproductive health services to encompass systematic population control measures.

The Family Planning Act of 1970 (Public Law 91-572) [7] emerged from this confluence of colonial governance structures and metropolitan demographic anxieties. The legislation’s stated purpose emphasized improving and expanding family planning services, yet its implementation in Puerto Rico revealed underlying objectives of demographic engineering. The Act authorized federal grants to state health authorities, with Puerto Rico included under the definition of “state” despite its territorial status, creating a framework where federal priorities dominated local health planning.

This study’s objective centers on analyzing population control policy in Puerto Rico during the 1969-1980 period. The analysis demonstrates how family planning programs functioned simultaneously as instruments of social welfare and mechanisms reinforcing political dependency, limiting Puerto Rico’s capacity for self-determined health policy.

The paper proceeds through a systematic examination of epidemiological and demographic patterns, policy origins, program implementation, and social consequences. The methodology section details the Historical Integrative Policy- Epidemiology Synthesis (HIPES) approach used to analyze these interconnected dimensions. Results present empirical evidence of policy impacts across demographic, economic, and social domains. The discussion situates findings within broader patterns of colonial health governance, while conclusions address implications for understanding population control in colonial and postcolonial contexts.

Methodology

This study employs a Historical Integrative Policy- Epidemiology Synthesis (HIPES) approach to analyze the relationship between family planning health policies and health outcomes including fertility-related outcomes in Puerto Rico from 1969 to 1980. HIPES combines three interlinked strands of analysis, each examining the when, what, and why of policy development and implementation within colonial governance structures based on the documentation contained in the source material-a dissertation entitled ‘Health and Development:

the United States/Puerto Rican Case’. It is a comprehensive, chronologically organized integrated analysis of U.S.-Puerto Rico health policy interaction drawn from a doctoral dissertation. This material includes legislative documents, health department reports, demographic statistics, and program evaluations spanning the study period. The analysis incorporates data from multiple tables documenting demographic transitions, funding patterns, and health outcomes, enabling triangulation across different data sources to validate findings [8].

The historical strand reconstructs the chronology of family planning policy formulation and implementation using legislative acts, administrative reports, and program. These policies are situated within the broader socio-political and economic context of U.S. governance, including shifts in political status and development priorities. This strand traces the evolution from early ambivalence toward birth control in the 1930s and 1940s, through the tacit acceptance of sterilization practices in the 1950s and 1960s, to the formal adoption of comprehensive family planning policies in 1970 [9]. The historical analysis examines how external pressures, including fears of Puerto Rican migration to the mainland and concerns about economic burden, shaped policy formation independently of local health needs assessment.

The epidemiological strand examines quantitative indicators fertility and birth rates, life expectancy, average family size, and maternal and infant health measures to track changes in population structure and size. This analysis utilizes comprehensive demographic data spanning from 1898 to 1980, enabling identification of long-term trends and policy impacts. The policy strand evaluates the intent, funding mechanisms, and administrative structures of major family planning programs. This analysis assesses the alignment between program objectives and local health needs, examining the adequacy of interventions and the extent to which policy design reflected external political and economic priorities. The examination includes detailed analysis of funding patterns, for example, federal contributions of $4,125,270 were matched by local funds of $4,575,567 in 1975-76.

The integrative synthesis merges historical narrative, epidemiological trends, and policy analysis. The framework draws on dependency theory to interpret how colonial relationships structured health policy formation, with metropolitan concerns about overpopulation and migration superseding local reproductive health needs [10-13].

Historical institutionalism within the HIPES framework illuminates how colonial governance structures became embedded in health systems, creating path dependencies that constrained future policy options. The analysis examines how federal funding mechanisms, administrative requirements, and program priorities reflected and reinforced colonial power relationships. These institutional arrangements meant that Puerto Rico’s health planning necessarily responded to federal categorical programs rather than developing comprehensive, locally determined health strategies [14-16].

The HIPES methodology enables examination of complex interactions between colonial governance, demographic change, and health policy, revealing how family planning programs in Puerto Rico served multiple and often contradictory objectives.

Results

Demographic and Policy Background

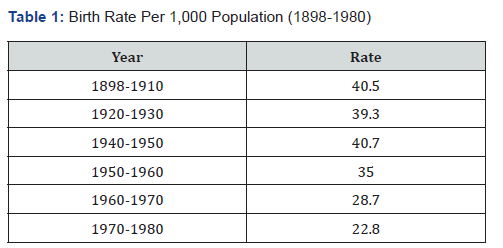

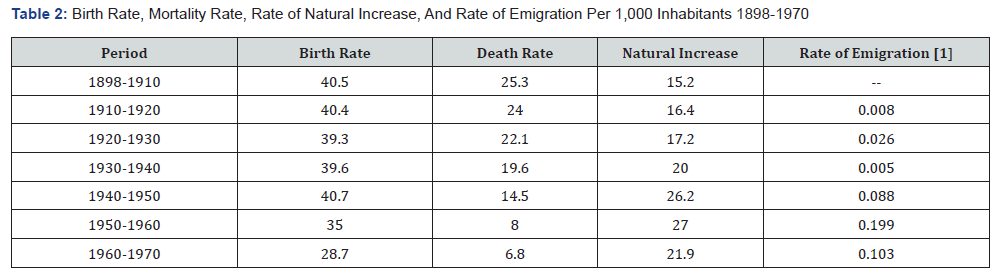

The demographic transformation of Puerto Rico from 1898 to 1980 reveals dramatic changes in population dynamics that provided the context for family planning interventions. The birth rate declined substantially from 40.5 per 1,000 population in the period 1898-1910 to 22.8 per 1,000 in 1970-1980, representing a reduction of nearly 50% over eight decades. (Table 1) This decline occurred alongside even more dramatic reductions in mortality, with the general mortality rate falling from 35.7 per 1,000 population in 1898 to 6.4 per 1,000 in 1980, a decrease of 82%. The differential between declining mortality and more gradually declining fertility created conditions of rapid natural population increase that peaked in the 1940-1950 period at 26.2 per 1,000 inhabitants (Table 1, Table 2) [17].

Source: Puerto Rico Department of Health, Annual Health Reports, years 1898 to 1980. The infant mortality rate has gone down by 92% between 1898 and 1980 (see Table 4). In the same period

Source: José L Vázquez Calzada, Puerto Rico, Department of Health, Vital Statistics, 1971.

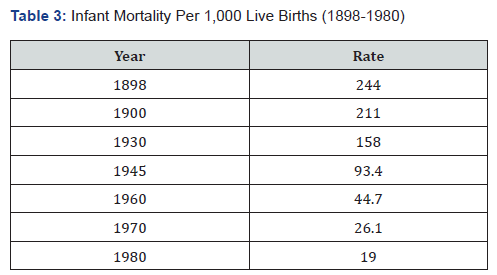

Infant mortality demonstrated particularly striking improvements, declining from 244.0 per 1,000 live births in 1898 to 19.0 per 1,000 in 1980, a reduction of 92%. (Table 3) This dramatic improvement in infant survival contributed significantly to population growth pressures that became central to U.S. policy concerns. Maternal mortality similarly declined from 64.6 per 10,000 live births in 1930 to 0.82 per 10,000 in 1980, representing a 98.73% reduction that reflected broader improvements in health infrastructure and medical care access [17].

As a result of the above, life expectancy at birth more than doubled during the period under examination, increasing from 30.36 years in 1898 to 73.11 years in 1980. By 1974, life expectancy reached 72.28 years, exceeding the U.S. average of 71.6 years and far surpassing the combined Latin American average of 63.6 years [17,18]. This demographic transition created an aging population structure, shifting from a pyramidal age distribution characteristic of high fertility and mortality societies to a more rectangular distribution associated with developed nations. (Table 3)

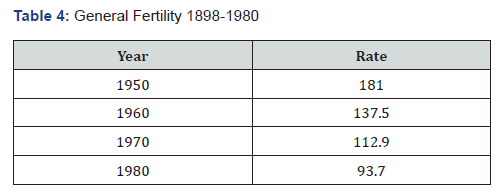

General fertility rates showed substantial decline from 181.0 births per 1,000 women ages 15-49 in 1950 to 93.7 in 1980 (Table 4) [17]. This fertility decline occurred across all socioeconomic groups but manifested differently based on class position. Poor women, facing economic pressures from low wages and increasing consumerism, initially embraced family planning as a strategy to reduce economic burdens. Middle and upper-class women, less economically constrained, initially maintained higher fertility due to religious beliefs opposing “unnatural” contraception [19]. (Table 4)

Source: Puerto Rico Department of Health, Annual Health Reports, years 1898 to 1980.

Source: Puerto Rico Department of Health, Annual Health Reports, year 1980.

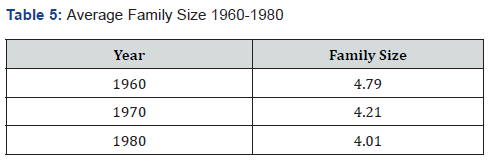

Average family size decreased from 4.79 in 1960 to 4.01 in 1980 (Table 5) [17], though this remained substantially higher than mainland U.S. averages. The persistence of relatively large family sizes despite decades of family planning efforts suggested complex relationships between policy interventions and reproductive behaviors. Cultural values, economic considerations, and religious beliefs mediated the impact of family planning programs on actual fertility outcomes.

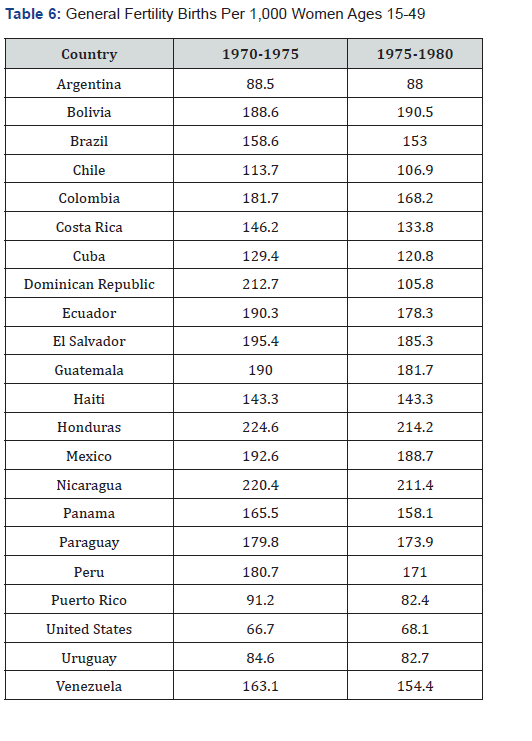

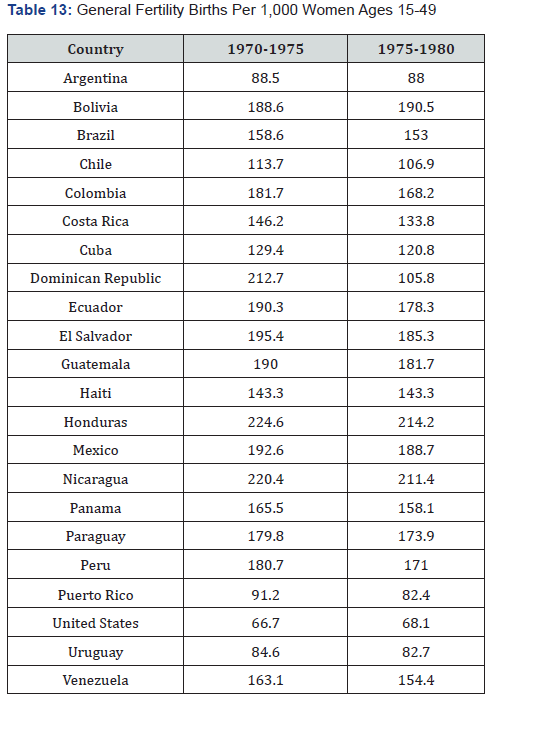

Comparative analysis with other Latin American and Caribbean nations revealed Puerto Rico’s distinctive demographic position. By 1970-1975, Puerto Rico’s general fertility rate of 91.2 births per 1,000 women ages 15-49 approached developed nation levels, substantially below regional comparators such as Honduras (224.6), Nicaragua (220.4), and Guatemala (190.0), and even below Argentina (88.5) and Uruguay (84.6). Only the United States, at 66.7, showed lower fertility among the compared nations (Table 5&6) [20].

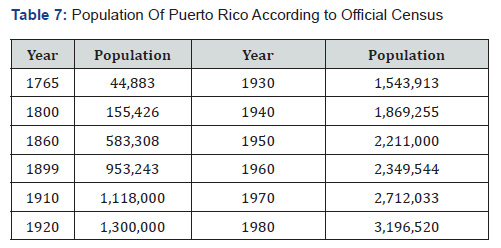

Origins of the Family Planning Agenda

The emergence of organized family planning in Puerto Rico reflected complex interactions between U.S. population policy goals, local economic pressures, and colonial governance structures. Analysis of population data reveals steady growth from 953,243 in 1899 to 3,196,520 in 1980, with particularly rapid increases during the mid-twentieth century (Table 7) [21]. This population growth, occurring in a territory of only 3,435 square miles, created a population density of 813 per square mile by 1974, among the highest globally [22]. (Table 7)

Source: Puerto Rico Department of Health, Annual Health Reports, years 1960 to 1980.

Source: “Selected World Demographic Indicators by Country,” Population Division, United Nations, 1980.

Source: Census of Puerto Rico, 1980.

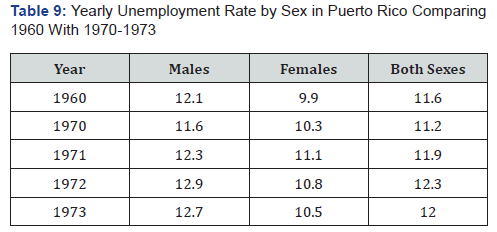

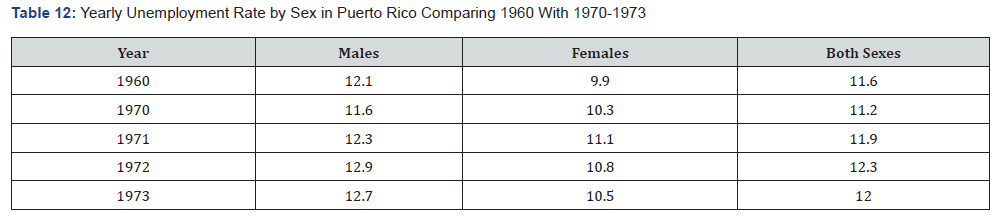

U.S. federal concerns about Puerto Rican population growth intensified during the 1960s, driven by multiple anxieties. Migration from Puerto Rico to the mainland accelerated dramatically, with net outmigration reaching 260,931 during 1940-1950, 502,006 during 1950-1960, and 225,229 during 1960-1970 (Table 8) [23]. Despite this massive emigration totaling nearly one million people over three decades, unemployment in Puerto Rico remained persistently high, reaching 12.0% in 1973 with male unemployment at 12.7% and female unemployment at 10.5% (Table 8&9) [24].

Source: Juan A. Sánchez Viera, “Puerto Rico: Patrones Migratorios,” University of Puerto Rico, School of Public Health, May 2, 1973 (mimeo).

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 16th Census of the United States, Occupations and Other Characteristics by Age, Bulletin No. 3 (Puerto Rico), p. 46, and Departamento del Trabajo de Puerto Rico, Empleo y Desempleo de Puerto Rico (various).

The demographic transition logic underlying U.S. intervention assumed that high birth rates constituted the primary impediment to Puerto Rico’s economic development. Federal policymakers viewed population growth as creating unsustainable demands on resources, infrastructure, and employment. This perspective ignored alternative explanations for economic challenges, including colonial economic structures, lack of autonomous development planning, and external control of key economic sectors [22]. Life expectancy data by sex during the crucial period of 1968-1974 showed continued improvements, with males reaching 69.38 years and females 76.30 years by 1974. These figures, comparable to developed nations, contradicted narratives of Puerto Rico as an impoverished territory requiring external intervention for basic health improvements. The relatively high life expectancy suggested that population growth resulted more from successful public health measures reducing mortality [25].

Labor force concerns provided additional motivation for U.S. population control efforts. The concentration of 58% of Puerto Rico’s population in urban centers by 1970 exacerbated unemployment and strained urban infrastructure. Young people under 25 experienced particularly high unemployment, creating fears of social instability. Federal policymakers viewed fertility reduction as a mechanism to reduce future labor force pressures, despite evidence that unemployment resulted from structural economic factors rather than simple population size [26].

Religious and cultural factors complicated the family planning agenda’s development. Puerto Rico’s predominantly Catholic population initially viewed large families as blessings, with the average family size of 8 children in 1898 reflecting both agricultural economic needs and religious values [27]. The transformation to an industrial economy altered these calculations, particularly for poor women who experienced the economic burdens of large families most acutely. By contrast, government policy wavered between tolerance and active support of birth control, reflecting political pressures from both religious authorities and modernizing forces [28].

The transition from ambivalence to active population control policy occurred gradually. Early initiatives in the 1930s and 1940s, including the establishment of Maternal Health Clinics that quietly provided contraceptive services, gave way to more explicit programs. The revision in 1946 to emphasize maternal health rather than birth control reflected political calculations during the optimistic early years of Operation Bootstrap. However, the government’s tacit acceptance of sterilization as a birth control method continued, creating conditions for its dramatic expansion in subsequent decades [29].

Program Implementation and Federal Control

The implementation of family planning programs in Puerto Rico from 1969 to 1980 revealed profound asymmetries in decision-making power and resource control between federal and local authorities. The Family Planning Act of 1970 established a framework whereby the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare maintained authority over program approval, funding allocation, and performance standards. This structure ensured that Puerto Rico’s family planning initiatives reflected federal priorities rather than locally determined health needs. Yearly demographic statistics for Puerto Rico from 1969 to 1974 documented program implementation this period. Live births fluctuated between 67,438 in 1970 and 71,117 in 1971, while maintaining relatively stable birth rates between 23.1 and 25.0 per 1,000 population. Infant mortality showed improvement from 29.7 per 1,000 live births in 1969 to 23.0 in 1974, though maternal deaths remained variable, ranging from 9 to 27 annually during this period [30].

Federal funding for family planning expanded dramatically during the 1970s, with federal contributions increasing from $1,478,157 in 1972-73 to $4,125,270 in 1975-76. The percentage of federal funding varied considerably, from 46.51% of total program funding in 1972-73 to 68.91% in 1974-75, before declining to 47.42% in 1975-76. These fluctuations reflected changing federal priorities and local matching capacity rather than systematic health planning based on population needs (Table 10) [31].

Source: Puerto Rico Department of Health, budgets for years 1972-73, 1973-74, 1974-75, and 1975-76.

State matching funds demonstrated Puerto Rico’s substantial financial commitment to family planning despite limited resources. Local contributions ranged from $1,400,000 in 1973- 74 to $4,575,567 in 1975-76, representing between 31.09% and 53.49% of total program funding. The requirement to match federal funds at these levels meant that 4.2% of Puerto Rico’s total health budget in 1975-76 was committed to family planning, constraining resources available for other health priorities [31]. Administrative control remained firmly in federal hands despite local financial contributions. The requirement that state plans receive approval from the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare before funding allocation ensured federal oversight of program design and implementation. Puerto Rico, classified as a “state” for funding purposes despite its territorial status, lacked the political representation to influence federal policy formation yet bore the financial and social consequences of program implementation.

The creation of the Family Planning Secretaryship within Puerto Rico’s Department of Health in 1974 represented an attempt to coordinate program implementation across the island’s 78 municipalities. Dr. Antonio Silva Iglesias, appointed to lead this effort, immediately initiated an aggressive program that emphasized sterilization as the primary method of fertility control. The government’s objective for fiscal year 1974-1975 included 5,000 sterilizations and a reduction in birth rate from 23.2 to 21.5 per 1,000 inhabitants, revealing the program’s emphasis on immediate demographic impact rather than comprehensive reproductive health services [20]. Service delivery patterns reflected federal categorical funding structures rather than integrated health planning. Family planning services operated separately from other maternal and child health programs, creating fragmentation and duplication. The emphasis on achieving numerical targets for contraceptive adoption and sterilizations overshadowed quality of care considerations and informed consent processes. Women seeking any form of reproductive health care often encountered pressure to accept sterilization, particularly in public facilities serving low-income populations [32].

General fertility rates during the program implementation period showed decline from approximately 112.9 births per 1,000 women ages 15-49 in 1970 to lower levels by decade’s end. However, these declines continued trends evident before massive federal intervention, raising questions about program effectiveness versus ongoing demographic transition. Comparative data showed Puerto Rico’s fertility rate of 91.2 in 1970-1975 and 82.4 in 1975-1980 remained higher than the United States (66.7 and 68.1 respectively) but had fallen below most Latin American nations [20,33].

Social and Economic Consequences

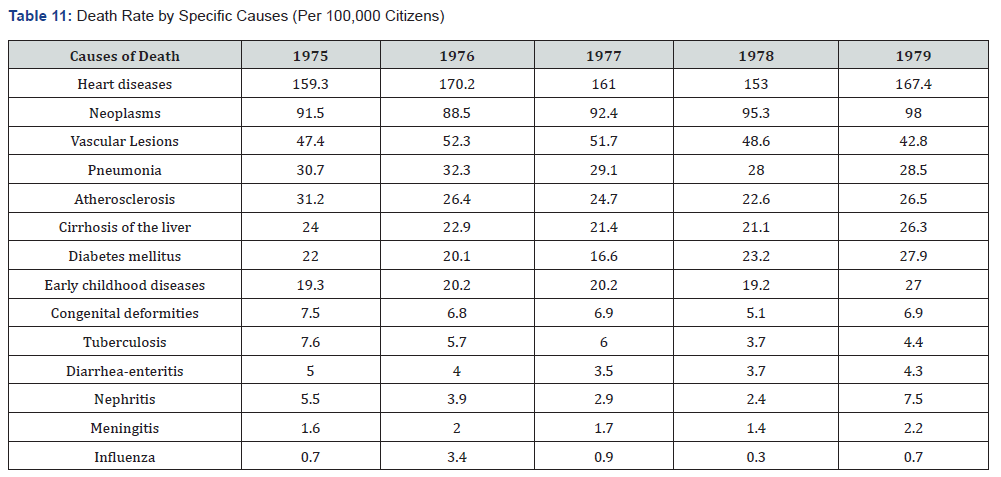

The implementation of family planning programs generated profound social and economic consequences that extended beyond demographic impacts to reshape Puerto Rican society. The intersection of high unemployment, persistent poverty, and aggressive population control measures created conditions where reproductive autonomy became subordinated to economic survival strategies and external demographic objectives. Death rates from specific causes during 1975-1979 revealed the changing disease burden that accompanied demographic transition. Heart diseases remained the leading cause of death, ranging from 153.4 to 170.2 per 100,000 citizens, followed by neoplasms (88.5 to 98.0 per 100,000) and vascular lesions (42.8 to 52.3 per 100,000) (Table 11) [34]. The prominence of chronic diseases associated with lifestyle and aging reflected successful control of infectious diseases but also indicated new health challenges requiring different interventions than those emphasized in family planning programs. (Table 11)

Unemployment patterns during the 1970s contradicted assumptions that population control would alleviate economic pressures. Despite massive outmigration and declining fertility, unemployment increased from 11.6% in 1960 to 12.0% in 1973, with rates reaching 17.5% by 1980 [6]. Male unemployment consistently exceeded female rates, reaching 12.7% in 1973 compared to 10.5% for women (Table 12). Youth unemployment remained particularly severe, suggesting that structural economic factors rather than population size drove joblessness [24]. The sterilization program’s impact proved especially consequential for Puerto Rican women. By the mid-1970s, Puerto Rico achieved the regrettable distinction of having the highest recorded incidence of female sterilization globally [35]. Nearly one-third of women of reproductive age had undergone sterilization by 1970-1972, with the procedure becoming normalized as the principal means of family size control among poor women. This prevalence reflected not genuine choice but constrained options within a context of poverty, limited contraceptive alternatives, and systematic pressure from medical providers [36]. (Table 12)

Economic dependency deepened despite population control efforts. By 1980, 420,172 families received welfare assistance while per capita income reached only $12,928 annually [33,37]. The persistence of poverty alongside aggressive fertility reduction challenged assumptions that population control would generate economic development. Instead, the focus on demographic solutions distracted from addressing structural causes of economic marginalization, including colonial economic relationships, external control of key industries, and limited local development planning capacity. Migration patterns revealed another dimension of population policy’s social consequences. The net outmigration of people between 1940 and 1970 represented a massive displacement that disrupted families and communities [38]. Government assistance for migration, including lobbying for low airfares and creating placement programs for farm workers, constituted unofficial population policy that complemented formal family planning programs. The creation of a “Migrant Division” in New York City with offices in eight other cities demonstrated the institutional infrastructure supporting population dispersal [26].

Source: Puerto Rico Department of Health, Vital Statistics. Years 1975-1979.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 16th Census of the United States, Occupations and Other Characteristics by Age, Bulletin No. 3 (Puerto Rico), p. 46, and Departamento del Trabajo de Puerto Rico, Empleo y Desempleo de Puerto Rico (various).

Religious and cultural impacts manifested in changing attitudes toward family, sexuality, and reproduction. The normalization of sterilization among all socioeconomic groups by the late 1960s represented a fundamental shift from earlier periods when religious beliefs dominated reproductive decisions. This shift created lasting tensions within Puerto Rican society between traditional values and modernizing pressures. Gender dynamics underwent transformation as women bore the primary burden of population control efforts. While women gained access to contraception that potentially enhanced autonomy, the emphasis on sterilization meant that many permanently closed reproductive options at young ages. The targeting of low-income women for sterilization reflected intersections of class, gender, and colonial power that rendered certain populations subject to demographic management [39]. The absence of comparable male sterilization programs revealed gendered assumptions about responsibility for fertility control.

The comparative analysis with other Latin American and Caribbean nations illuminated Puerto Rico’s unique position. General fertility rates for 1975-1980 showed Puerto Rico at 82.4 births per 1,000 women ages 15-49, substantially below regional averages but still above the United States at 68.1 (Table 13) [20]. This intermediate position reflected Puerto Rico’s liminal status neither fully developed nor underdeveloped, neither independent nor incorporated that shaped both demographic patterns and policy responses. (Table 13)

Source: “Selected World Demographic Indicators by Country,” Population Division, United Nations, 1980.

Synthesis of Results

The evidence reveals fundamental contradictions in Puerto Rico’s family planning program from 1969 to 1980. While demographic indicators showed declining fertility and improved health outcomes, these changes continued trends established before massive federal intervention and occurred alongside persistent unemployment, deepening poverty, and large-scale emigration. The program’s emphasis on sterilization as the primary method of fertility control, achieving global highs in female sterilization rates, demonstrated how colonial power relations transformed reproductive health services into instruments of population management.

Federal funding mechanisms that required substantial local matching while maintaining external control over program design exemplified colonial governance patterns. Puerto Rico committed significant resources up to 52.58% of total program funding in 1975-76 yet lacked meaningful input into policy making. This arrangement created dependency while constraining autonomous health planning capacity. The categorical nature of federal funding prevented integrated approaches to health and development, forcing Puerto Rico to implement programs designed for mainland contexts without adaptation to local conditions.

The failure of population control to address unemployment, poverty, and economic dependency revealed the inadequacy of demographic solutions to structural problems. Despite achieving fertility rates approaching developed nation levels, Puerto Rico continued experiencing economic marginalization that drove massive emigration and welfare dependency.

Discussion

The empirical evidence presented reveals how colonial logics of population containment and economic management fundamentally shaped Puerto Rico’s family planning agenda from 1969 to 1980. As demonstrated in (Table 10), federal funding reached $4,125,270 by 1975-76, requiring Puerto Rico to commit matching funds of $4,575,567, representing 52.58% of total program costs despite the island’s limited fiscal capacity. This funding structure exemplified dependency relationships where metropolitan priorities determined local resource allocation while constraining autonomous health planning.

The application of dependency theory illuminates how Puerto Rico’s reproductive health policies emerged not from self-determined needs assessment but from U.S. geopolitical, demographic, and economic concerns [40]. The dramatic decline in birth rates from 25.0 per 1,000 population in 1969 to 23.1 in 1974 [25] occurred within a framework where federal authorities-maintained control over program design. Local health officials administered programs conceived in Washington, with limited capacity to adapt interventions to Puerto Rican contexts or health priorities. Analysis revealed how population control served multiple metropolitan interests simultaneously. The net outmigration of nearly one million Puerto Ricans between 1940 and 1970 (Table 8) generated concerns about demographic pressures on mainland cities, particularly New York. The targeting of low-income women for sterilization reflected intersections of class and colonial power, rendering certain populations subject to demographic management [41].

The transformation of sterilization from a marginal practice to the predominant form of contraception exemplified how colonial medical systems could reshape bodily autonomy and reproductive futures. By achieving the highest recorded incidence of female sterilization globally, Puerto Rico became a site where metropolitan anxieties about overpopulation were addressed through permanent measures [42]. The normalization of this irreversible procedure among women of all socioeconomic classes by the late 1960s demonstrated the pervasive influence of colonial health governance on intimate aspects of life.

Policy design systematically excluded Puerto Rican participation in decision-making processes. Despite classification as a “state” for funding purposes, Puerto Rico lacked voting representation in Congress where family planning legislation originated. The requirement for federal approval of state plans before funding allocation ensured metropolitan oversight while denying local communities’ meaningful input into programs affecting their reproductive lives. This absence of democratic participation violated principles of self-determination while imposing external definitions of appropriate family size and structure.

The lack of transparency in program operations further undermined accountability. Women seeking reproductive health services often encountered pressure to accept sterilization without full information about its permanence or alternatives [43]. The emphasis on achieving numerical targets for sterilizations, exemplified by the government’s objective of 5,000 procedures in fiscal year 1974-1975, prioritized demographic impact over informed consent and quality of care. Payment structures that rewarded providers more for sterilization than reversible contraception created systematic biases toward permanent methods. The persistence of high unemployment despite fertility decline challenged fundamental assumptions underlying population control policies. As shown in (Table 9), unemployment remained at 12.0% in 1973, with youth unemployment particularly severe despite decades of outmigration and falling birth rates. This evidence revealed that joblessness resulted from structural economic factors including external control of industries, limited local development planning, and colonial trade relationships rather than population pressure [44]. The continued emphasis on fertility reduction despite these contradictions demonstrated how colonial ideologies persisted even when evidence contradicted their premises.

Public participation in family planning programs remained severely constrained by established governance structures. Community organizations, women’s groups, and local health advocates lacked formal channels to influence program design or implementation. The top-down imposition of demographic targets without community consultation reflected broader patterns of colonial administration where technical expertise and metropolitan power superseded local experience and preferences. This exclusion of Puerto Rican voices from decisions about their own reproductive futures exemplified the fundamental powerlessness characteristic of colonial subjects.

The interaction between family planning and broader colonial economic policies created contradictions. While promoting fertility reduction as economic development strategy, federal policies simultaneously maintained economic structures that perpetuated dependency. The requirement to use U.S. shipping for trade, restrictions on autonomous trade relationships, and external control of key industries ensured continued economic marginalization regardless of demographic changes. Family planning thus served to deflect attention from structural causes of poverty.

Gender dimensions of colonial population control revealed how women bore disproportionate burdens of demographic management. The exclusive focus on female sterilization, with minimal comparable programs for men, reflected patriarchal assumptions about reproductive responsibility [45]. Poor women faced particular pressures, confronting choices between economic survival and reproductive autonomy within contexts of limited employment, inadequate wages, and welfare policies that penalized work. The intersection of poverty, gender, and colonial status created conditions where sterilization became a survival strategy rather than a genuine choice.

The health system impacts of prioritizing family planning over comprehensive reproductive health services created lasting distortions. The commitment of 4.2% of Puerto Rico’s total health budget to family planning by 1975-76 occurred while other health needs remained unaddressed. The categorical nature of federal funding prevented integrated approaches to maternal and child health, sexually transmitted infections, and general reproductive health services. Women seeking prenatal care, treatment for reproductive health conditions, or general gynecological services encountered systems oriented primarily toward fertility limitation.

Comparative analysis with other Latin American contexts illuminates the specifically colonial dimensions of Puerto Rico’s experience. While many Latin American nations implemented family planning programs during this period, Puerto Rico’s political status created unique outcomes. Unlike independent nations that could negotiate terms of international family planning assistance or reject programs inconsistent with national priorities, Puerto Rico faced direct imposition of federal programs without recourse to sovereignty claims [46]. The achievement of fertility rates below all Latin American comparators except the United States by 1975-1980 (Table 6) did not reflect successful development but rather the intensive application of colonial population management.

Conclusion

The analysis of family planning policies in Puerto Rico from 1969 to 1980 reveals how population control functioned as a mechanism of colonial governance with profound and lasting consequences for reproductive autonomy and health sovereignty. The evidence demonstrates that these programs, funded through a combination of $4,125,270 in federal money and $4,575,567 in required local matching funds by 1975-76, served U.S. demographic and economic interests rather than addressing locally-determined health needs. The achievement of the world’s highest female sterilization rates, the reduction of birth rates from 25.0 to 23.1 per 1,000 population between 1969 and 1974, and the continued emphasis on fertility limitation despite persistent unemployment and poverty reveal the subordination of Puerto Rican reproductive health to metropolitan population control objectives.

The Historical Integrative Policy-Epidemiology Synthesis methodology illuminated the complex interactions between colonial governance structures, demographic policies, and health outcomes. By examining the historical evolution of family planning programs, analyzing epidemiological impacts, and evaluating policy mechanisms, this approach has revealed how seemingly technical health interventions functioned as instruments of colonial management. The integration of these analytical strands demonstrates that family planning in Puerto Rico cannot be understood solely as a public health measure but must be recognized as a manifestation of colonial power relations that denied self-determination while imposing external demographic objectives.

The findings affirm that Puerto Rico’s population control agenda represented a top-down colonial policy with measurable demographic effects that extended far beyond fertility reduction. The systematic exclusion of Puerto Rican communities from policy formation, the lack of transparency in program implementation, and the absence of accountability mechanisms violated principles of democratic governance and health equity. The requirement that Puerto Rico match federal funds at the highest possible rate while lacking voting representation in Congress led to limited representation in health policy, perpetuating colonial relationships through health governance structures.

The broader implications of this analysis extend to understanding population control policies in other colonial and postcolonial contexts where demographic interventions continue under development rationales. The Puerto Rican experience demonstrates how health policies can function as vehicles for maintaining colonial relationships even when formal political arrangements suggest autonomy. The persistence of external control over reproductive health policies, the prioritization of demographic targets over comprehensive health services, and the use of health funding to enforce dependency reveal patterns likely repeated in other contexts were power asymmetries shape health governance.

The value of historical-demographic and policy analysis in uncovering these dynamics are evident. Without systematic examination of funding patterns, demographic data, and policy mechanisms, the colonial dimensions of family planning programs might remain obscured behind technical discourses of public health and development. This study’s documentation of how federal categorical funding constrained local health planning, how sterilization became normalized through systematic pressures rather than free choice, and how population control failed to address underlying causes of poverty provides essential evidence.

Future research must examine the long-term consequences of this period’s intensive sterilization program on Puerto Rican families and communities. Understanding these lasting impacts requires longitudinal analysis that traces how colonial population control reverberates through generations, affecting not only demographic patterns but also cultural values, gender relations, and collective identity. The contemporary relevance of these findings extends to current debates about Puerto Rico’s political status and health system reform. As Puerto Rico continues to navigate complex relationships with federal health programs, including contemporary Medicaid and public health funding, the patterns identified in this study external control, mandatory matching requirements, categorical funding structures, and limited local autonomy persist in modified forms. Recognition of these historical patterns provides essential context for understanding current health governance challenges and the constraints on achieving health sovereignty within colonial frameworks.

This analysis demonstrates that meaningful reproductive health policy in colonial contexts requires more than technical improvements or increased funding. It demands fundamental transformation of power relationships that determine who makes decisions. The Puerto Rican experience from 1969 to 1980 stands as a cautionary tale of how health interventions, however well-intentioned in their stated objectives, can serve as instruments of colonial domination when implemented without genuine self-determination, democratic participation, and respect for reproductive autonomy. Only through recognition of these dynamics can future health policies avoid perpetuating historical patterns of demographic management disguised as public health policies.

References

- Public Law 447: Joint Resolution-Approving the constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico which was adopted by the people of Puerto Rico on March 3, 1952 (n.d.).

- Steward JH, Manners RA, Robert A, Wolf ER, Padilla E, et al. (1956) The people of Puerto Rico: a study in social anthropology. University of Illinois Press.

- Santos JD (1971) The Structure of Dependence. In: Readings in U.S. Imperialism, Fann, K.T. and Hodges, D.C. (eds.). Boston: Porter Sargent

- Puerto Rico: Information for Status Deliberations: Briefing Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on Insular and International Affairs, Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, House of Representatives Pp: 1-71.

- William Barclay, Joseph Enright, Reid T Reynolds (1970) Population Control in The Third World. NACLA Newsletter 4(8): 1-16.

- (1980) Puerto Rico Department of Labor, Statistics Bureau, Unemployment Figures.

- Public Law 91-572: Family Planning Services and Population Research Act of 1970 Pp: 1504-1508.

- Gonzalez AR (1994) Health and development: The United States/Puerto Rican case [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Johns Hopkins University.

- Ramírez de Arellano A, Seipp C (1983) Colonialism, Catholicism & Contraceptives: A History of Birth Control in Puerto Rico. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 75.

- Fann KT and Hodges DC (1971) Bodenheimer Suzzane, Dependency and Imperialism: The Roots of Latin American Underdevelopment. In: Readings in U.S. Imperialism (eds). Boston: Porter Sargent Pp: 1-397.

- Oliveira FA de (2024) Dependency Theory after Fifty Years: The Continuing Relevance of Latin American Critical Thought. Journal of Latin American Studies 56(2): 355-357.

- Sanchez O (2003) The Rise and Fall of the Dependency Movement: Does It Inform Underdevelopment Today? EIAL-Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y El Caribe 14(2).

- Cardoso FH, Faletto E (1979) Dependency and development in Latin America 227.

- Steinmo S (2008) Historical institutionalism. Approaches and Methodologies in the Social Sciences: A Pluralist Perspective Pp: 118-138.

- Pan W, Hosli MO, Lantmeeters M (2023) Historical institutionalism and policy coordination: origins of the European semester. Evolutionary and Institutional Economics Review 20(1): 141-167.

- Fioretos O, Falleti TG, Sheingate A (2016) The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism.

- Puerto Rico Department of Health, Annual Health Reports, years 1898 to 1980 (n.d.).

- (1980) United Nations “Selected World Demographic Indicators by Countries,” Population Division, New York.

- Savage W (1982) Taking liberties with women: Abortion, sterilization, and contraception. International Journal of Health Services,12(2): 293-308.

- Selected World Demographic Indicators by Country," Population Division, United Nations. (1980).

- Census of Puerto Rico (1980) Library Bureau of the Census. (N.D.) Pp: 1-522.

- Morales Carrión A, Caro Costas AR (1983) Puerto Rico, a political and cultural history (Arturo Morales Carrión, AR Caro Costas, & American Association for State and Local History, Eds.).

- Sánchez Viera Juan A (1973) “Puerto Rico: Patrones Migratorios,” University of Puerto Rico, School of Public Health (mimeo).

- S. Bureau of the Census, 16th Census of the United States, Occupations and Other Characteristics by Age, Bulletin No. 3 (Puerto Rico), p. 46, and Departamento del Trabajo de Puerto Rico, Empleo y Desempleo de Puerto Rico (various). (n.d.).

- Calzada V (2025) La Población de Puerto Rico y su Trayectoria Histó San Juan.

- Earnhardt KC (1982) Development planning and population policy in Puerto Rico: from historical evolution towards a plan for population stabilization Pp: 1-214.

- Halsted Murat (1899) Pictorial History of America’s New Possessions, Chicago: The Dominion Company.

- Clark VS (Victor S 1868-1946) (1930). Porto Rico and its problems.

- (1946-47) Puerto Rico Department of Health, Annual Report to the Governor (n.d.).

- (1969-1974) Puerto Rico Department of Health, Vital Statistics Pp: 1-112.

- Puerto Rico Department of Health, budgets for years 1972-73, 1973-74, 1974-75, and 1975-76. (n.d.).

- Herold JM, Warren CW, Smith JC, Rochat RW, Martinez R, et al. (1986) Contraceptive use and the need for family planning in Puerto Rico. Family planning perspectives 18(4): 185-192.

- (1980) Puerto Rico Planning Board, Area of Economic Research and Evaluation, Bureau of Economic Accounts and Census, Annual Report.

- (1975-1979) Puerto Rico Department of Health Vital Statistics (n.d.).

- Cofresí Emilio (1951) Realidad Poblacional de Puerto Rico, San Juan PR.

- Earnhardt Kent (1969) “Puerto Rico.” In: Politics and Population in the Caribbean. Segal, Aaron, (ed.) Río Piedras, P.R.: Institute of Caribbean Studies, University of Puerto Rico.

- (1980) Puerto Rico Department of Social Services, Food Stamps Program.

- Presser H B (1973) Sterilization and fertility decline in Puerto Rico. 211.

- Still J W (1968) The three levels of human life and death, the presumed location of the soul, and some of the implications for the social problems of abortion, birth control and euthanasia. The Medical annals of the District of Columbia 37(6): 316-318.

- Bonilla F, Campos R (1982) “Imperialist Initiative and the Puerto Rican Worker”, Contemporary Marxism No. 5 Pp: 1-18.

- Cordero Rafael de J (1966) “The Future of an Island,” Los Angeles: University of California Medical Center (mimeo).

- Boring CC, Rochat RW, Becerra J (1988) Sterilization regret among Puerto Rican women. Fertility and sterility 49(6): 973-981.

- Fish MS (1981) “Euthanasia: Where Are We? Where Are We Going?” Journal of the Medical Society of New Jersey 78(12): 812-815.

- Vázquez Calzada José L (1966) “El Desbalance entre Recursos y Población en Puerto Rico,” University of Puerto Rico, Center for Demographic Studies (mimeo).

- Saliva Luis A (1950) History of Puerto Rico's storms, San Juan PR: La Milagrosa Printing House.

- (1976) Puerto Rico Comprehensive Reform Law, Law 11 of June 23.