Is There an Up-To-Date Evidence-Based Myocardial Infarction Therapy Model in Acute Phase of Rehabilitation?

Kinga Balla*, Karl Konstantin Haase

Kreiskliniken Reutlingen GmbH, Steinenberg Str 31,72764 Reutlingen, Germany

Submission: June 26, 2024; Published: August 12, 2024

*Corresponding author: Kinga Balla, Kreiskliniken Reutlingen GmbH, Steinenberg Str 31,72764 Reutlingen, Germany. Email: kinga.balla@kliniken-rt.de

How to cite this article:Kinga Balla*, Karl Konstantin Haase. Is There an Up-To-Date Evidence-Based Myocardial Infarction Therapy Model in Acute Phase of Rehabilitation?. 2024; 9(2): 555758. DOI: 10.19080/JOJPH.2024.09.555758

Keywords: Acute Myocardial Infarction; Reutlingen Myocardial Infarction Therapy Model; Physiotherapy; Rehabilitation; Mobilization plan

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (MI) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the world [1]. The global prevalence of myocardial infarction (sample size N=35 million), for < 60 years individuals was detected to be 3.8% and for ≥ 60 years 9.5% [1], representing in total three million people worldwide [2]. An acute MI may lead to irreversible damage to the heart muscle due to a lack of oxygen caused by decreased coronary blood flow: available oxygen supply cannot meet oxygen demand. Associated symptoms include [3-4] chest pain or pressure, shoulder or arm pain, sweating, shortness of breath, nausea, anxiety, etc. Myocardial ischemia may be associated with ECG changes and elevated biochemical markers such as cardiac troponins [5]. The pathology is divided into two categories: MI with ST-elevation (STE-MI) and non-ST elevation MI (NSTE-MI). The best-known modifiable risk factors for coronary artery disease are [6]: smoking, abnormal lipid profile, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, adipositas, lack of physical activity, psychosocial factors such as depression [7] etc. The primary treatment form for MI is the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), which enables the reperfusion of the heart and restores the blood flow [2]. An early PCI treatment is the key to a good prognosis and cardiac rehabilitation.

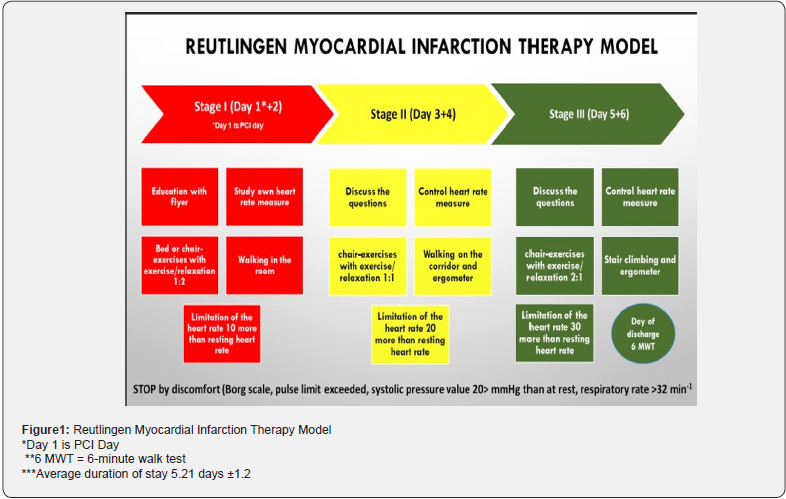

The rehabilitation process is divided into three phases [8]. The first phase is the clinical phase, which begins with the in-hospital setting after intervention (PCI). Phase II is outpatient cardiac rehabilitation, which commences about the third week after PCI and lasts three to four weeks. In the third phase or post-cardiac rehabilitation, patients receive encouragement to maintain an active lifestyle and continue the exercises. The period of the first phase (clinical) is the most vital phase of cardiac rehabilitation [8-9]. Haykowsky et al. [10] conducted a meta-analysis and found that delaying the start of training leads to a poorer baseline situation in terms of left ventricular function. This confirms the need for daily therapy immediately after MI [11-12]. Although phase I is recognized as the most important phase in MI rehabilitation [8-13] and evidence-based studies are available [3-12], myocardial infarction mobilization plans can hardly be found in the international or national literature [14-15] or are no longer up to date due to changing conditions [16-17], e.g. shortened hospital stay and therapy times. To close this gap, an evidence-based therapy model (Reutlingen Myocardial Infarction Therapy Model) was developed for MI patients in acute phase I of rehabilitation (hospitalization), so that we can provide our patients with the best possible care (Figure 1).

The Reutlingen Myocardial Infarction Therapy Model is based on the Heidelberg model [17], supplemented with two further methods known from literature, the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) and ergometer training. The 6 MWT is a wildly used, simple, low cost, validated submaximal exercise test to assess the daily activity performance by patients with heart diseases [18-19]. According to studies, ergometer training is an optimal form of therapy for MI patients from the second rehabilitation phase [20]. There are fewer studies on ergometer training [21] or motorized exercise training (MOTOmed [22]), in the first phase of rehabilitation. The ergometer test according to the Bruce protocol [23] as a resilience/stress test in the first MI phase has been tested as safe and efficient [24-25].

Conclusion

As the general length of stay in hospital decreases after an MI, a modern, effective yet safe treatment method is needed.

References

- Salari N, Morddarvanjoghi F, Abdolmaleki A, Rasoulpoor S, Khaleghi AA, et al. (2023) The global prevalence of myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 23(1): 206.

- Mechanic OJ, Gavin M, Grossman SA (2023) Acute Myocardial Infarction. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, et al. (2004) ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction-executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation 110(5): 588-636.

- DeVon HA, Mirzaei S, Zègre‐Hemsey J (2020) Typical and Atypical Symptoms of Acute Coronary Syndrome: Time to Retire the Terms. J Am Heart Assoc 9(7): e015539.

- Ojha N, Dhamoon AS (2024) Myocardial Infarction. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Anand SS, Islam S, Rosengren A, Franzosi MG, Steyn K, et al. (2008) Risk factors for myocardial infarction in women and men: insights from the INTERHEART study. Eur Heart J 29(7): 932-940.

- Balla K, Haase KK (2024) Investigation of Socio-Demographic Factors Affecting the Quality of Life and the Anxiety/Depression Scores in the Acute Myocardial Infarction Phase-Observational Study. Eur J Public Health Stud 7(1): 1-17.

- de Macedo RM, Faria-Neto JR, Costantini CO, Casali D, Muller AP, et al. (2011) Phase I of cardiac rehabilitation: A new challenge for evidence-based physiotherapy. World J Cardiol 3(7): 248-255.

- Balla K, Haase KK (2024) Cardiovascular Fitness, Quality of Life and Depression/Anxiety Score in Patients after Myocardial Infarction and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention under Physiotherapeutic Treatment-Observational Study. Eur J Physiother Rehabil Stud 4(1): 1-15.

- Haykowsky M, Scott J, Esch B, Schopflocher D, Myers J, et al. (2011) A meta-analysis of the effects of exercise training on left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction: start early and go longer for greatest exercise benefits on remodeling. Trials12: 92.

- Tessler J, Bordoni B (2023) Cardiac Rehabilitation. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Moraes-Silva IC, Rodrigues B, Coelho-Junior HJ, Feriani DJ, Irigoyen MC (2017) Myocardial Infarction and Exercise Training: Evidence from Basic Science. In: Xiao J, editor. Exercise for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Treatment Pp.139-153.

- Zhang YM, Lu Y, Tang Y, Yang D, Wu HF, et al. (2016) The effects of different initiation time of exercise training on left ventricular remodeling and cardiopulmonary rehabilitation in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Disabil Rehabil 38(3): 268-276.

- Brzek A, Nowak Z, Plewa M (2002) Modified programme of in-patient (phase I) cardiac rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction. Int J Rehabil Res 25(3): 225-229.

- Qu B, Hou Q, Men X, Zhai X, Jiang T, et al. (2021) Research and application of KABP nursing model in cardiac rehabilitation of patients with acute myocardial infarction after PCI. Am J Transl Res 13(4): 3022-3033.

- Hüter-Becker Antje, Dölken Mechthild, Göhring Hannelore, Solodkoff Christiane von, Solodkoff Michael (2004) Physiotherapie in der Inneren Medizin.Thieme1: 17.

- Hüter-Becker Antje, Dölken Mechthild (2018) Physiotherapie in der Inneren Medizin.Thieme 4: 17.

- Ferreira PA, Ferreira PP, Batista AKMS, Rosa FW (2015) Safety of the Six-Minute Walk Test in Hospitalized Cardiac Patients. Int J Cardiovasc Sci 28(1): 70-77.

- Diniz LS, Neves VR, Starke AC, Barbosa MPT, Britto RR, et al. (2017) Safety of early performance of the six-minute walk test following acute myocardial infarction: a cross-sectional study. Braz J Phys Ther 21(3): 167-174.

- Gloc D, Nowak Z, Nowak-Lis A, Gabryś T, Szmatlan-Gabrys U, et al. (2021) Indoor cycling training in rehabilitation of patients after myocardial infarction. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 13(1): 151.

- Matsunaga A, Masuda T, Ogura MN, Saitoh M, Kasahara Y, et al. (2004) Adaptation to Low-Intensity Exercise on a Cycle Ergometer by Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Phase I Cardiac Rehabilitation. Circ J 68(10): 938-945.

- Bartík P, Vostrý M, Hudáková Z, Šagát P, Lesňáková A, et al. (2022) The Effect of Early Applied Robot-Assisted Physiotherapy on Functional Independence Measure Score in Post-Myocardial Infarction Patients. Healthcare10(5): 937.

- Heil DP (2001) ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 6th Med Sci Sports Exerc 33(2): 343.

- Gill TM, DiPietro L, Krumholz HM (2000) Role of exercise stress testing and safety monitoring for older persons starting an exercise program. JAMA 284(3): 342-349.

- Senaratne MP, Smith G, Gulamhusein SS (2000) Feasibility and safety of early exercise testing using the Bruce protocol after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 35(5): 1212-1220.