On the Importance of Patient-Centred Care

Natasha James*

4th year medical student, Newcastle University, Malaysia.

Submission: April 28, 2023; Published: June 01, 2023

*Corresponding author: Natasha James, 4th year medical student, Newcastle University, Malaysia.

How to cite this article:Natasha J. On the Importance of Patient-Centred Care. JOJ Pub Health. 2023; 7(4): 555717. DOI: 10.19080/JOJPH.2023.07.555717

Abstract

In recent times, the importance of non-biological factors has been recognized in dealing with the health of individuals, and thus, a previously more biologically centered healthcare approach has been steered to a more holistic one. This approach aims to incorporate all aspects of an individual into their care, including their psychological and social entities. This paper will explore the different contributors to health outcomes including health inequalities, the health and illness beliefs of patients, the different ways in which consultations are run, the pathways of care, and the role of multidisciplinary teamwork in patient care. Real patient examples will be incorporated to supplement the various determinants of health explained within this paper.

Keywords: Biopsychosocial; General Medical Council; Primary health care teams; clinical reasoning

Introduction

Patient as a person

The idea of the mind being viewed as a separate entity to the body is captured in the phrase “Cartesain Dualism”. This perspective can be traced to the 1600s when French scientist – Rene Descartes claimed that pain was purely caused by the sensory nervous system [1]. Later in the 1900s, American psychiatrist George Engel expressed that pain experienced by patients would be better understood, if the psychological and social contributors to their suffering were addressed along with the biological ones (Figure 1) [2]. This perspective of health, termed the Biopsychosocial (BPS) model, was more comprehensive than the purely biomedical one employed in the past [3]. The BPS model has been described as the vital inclusion of a patient’s subjective experiences towards their “accurate diagnosis, health outcomes, and humane care” [4]. It is thus, a comparatively more patient-centred approach to healthcare.

Patient-centeredness places an emphasis on centring healthcare around the health requirements and outcomes that an individual wants for themselves. Making the patient’s views and beliefs central to their healthcare is representative of the mutualistic form of the doctor-patient relationship. In this framework, patients are encouraged to work alongside doctors in decision-making, for the betterment of their health. Healthcare providers attempt to treat patients, not just with their clinical expertise, but also with their human attributes which enable emotional and mental relatability to the patient [5]. This approach is contrasted by the paternalistic form of doctor-patient relationship which has dominated consultations in the past, and still prevails in some cultures - where the doctor takes on a more dominant role while the patient is less assertive [6].

Health inequalities

Social class is a major contributor to ill health, especially in countries without free healthcare. This is because the wealth status of an individual impacts the quality of healthcare they can access. This is the underlying basis for health inequalities. An American medical study found that regardless of quality of cancer treatment, the ultimate therapeutic effect on patients depended on their race and social status [7].

A pregnant patient I interviewed within a Malaysian hospital, stated that the third-class post-labour maternity ward in the hospital, was overfilled with patients, and only one fan in the whole room. The toilet had one bucket and ladle to be shared between all the women. Post – labour, the food provided was a single patty and a biscuit. In the first class, however, there were fans all around, improved cleanliness, and better-quality food. This demonstrates how social class impacts the quality of care received by patients.

Health inequalities are caused by a variety of factors shown in (Figure 2) [8], which depicts how unequal distribution of income, power, wealth, and poverty, marginalisation, and discrimination, cause health inequalities. These can impact our biological, social, and psychological outcomes. An example of how biological outcomes can be impacted by social class, is when families living in poverty have children with low birth weights, who then become more likely to develop conditions for which low birth weight is a risk factor.

This then financially burdens the family due to them having to pay for the required treatment [9]. People belonging to lower social classes have a greater likelihood of being uneducated, and working high-risk jobs, both of which increases their exposure to risk factors, such as toxic fumes, smoking, drinking, eating fast food regularly, and not getting enough physical activity [10]. These then worsen their health outcomes. It has been found that “class I men” (males belonging to a high social class) live up to 7 years longer than “class V men” (males belonging to a lower social class). This affirms the more disadvantaged stance held by the lower-class population in terms of mortality, morbidity, and health [11].

Patient health and illness beliefs

The beliefs patients hold about health and illness are important in determining their health status and health-seeking behaviours. In the 1980s, Blaxter conducted a study to determine the layperson’s definition of health. His findings were split into two categories: ‘negative definitions of health’ where health was defined as “being free of symptoms of illness” and ‘positive definitions of health’ where health was defined as “being physically fit” and having “psychological and social wellbeing”. His findings were further dissected by sociologists who found that definitions of health varied between social class, race, and age [12].

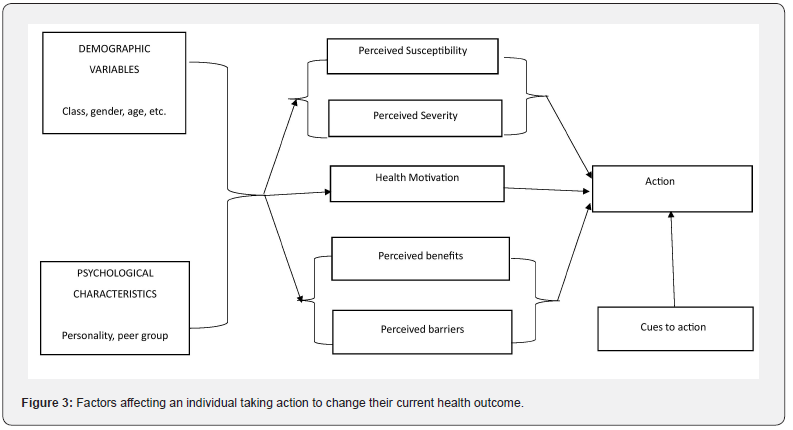

It is important to consider variable definitions of health held by individuals when assessing why help-seeking behaviours differ amongst them. One patient I met during a clinical visit knew she had hypertension yet viewed herself as “very healthy”. She believed this because she was able to carry out her daily activities normally. Although hypertension is a predominantly asymptomatic condition till complications arise, the health belief held by this patient implies that she would be less likely to seek medical help for conditions that other people would seek help for. Thus, the health beliefs of patients influence their use of selfcare and determine when they decide to avail of medical care. The health belief model suggests that an individual’s likelihood of seeking help is dependent on their perceived benefits and risks of doing so. The six constituents of this model are perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy, which are illustrated in (Figure 3) [13].

This model suggests that individuals are likelier to take action against developing a condition if they:

i. perceive themselves as having a risk of developing it (perceived susceptibility),

ii. feel that it has serious consequences (perceived severity),

iii. believe that there is potential for them to be protected from the harmful effects of the condition (perceived benefits) and

iv. do not perceive any negative outcomes coming from their help- seeking behaviours (perceived barriers) [14].

The sociologist Irving Zola proposed five triggers that might describe why individuals seek medical help. They were: “the occurrence of an interpersonal crisis, perceived interference with social and personal relations, perceived interference with vocational and physical activity, sanctioning by other people, and a temporalizing of symptoms where the sufferer has specific ideas about how long certain complaints should last” [15]. The Biomedical Model of Health relies on a purely biological explanation for illness as the cornerstone for finding treatments and interventions [16]. The concepts constituting biomedical models of health are as follows [17]: Symptoms of ill health are caused by the malfunctioning of a body part, resulting in disease.

i. All diseases eventually cause symptoms, and although factors extraneous to biological ones may determine the outcomes of the disease, they are not involved in the disease’s development.

ii. Health is the absence of disease.

iii. Mental issues, including emotional conflict, are not related to other disturbances in body functioning.

iv. Patients are victims to their condition, and are helpless with regards to the presence and because of their illness

v. The patient passively receives treatment, and their compliance with treatment is expected.

As stated earlier, the BPS model offers a more comprehensive explanation for health and illness, incorporating psychological and social determinants of illness. A similar concept is encompassed in the social model of health. This model attributes the cause of illness to a range of factors including environmental, social, economic, and cultural ones. The social model of health acknowledges the absence of disease as being a part of the definition of health but does not claim it as being the sole determinant. It is thus a more holistic and less reductionist approach to health compared to the Biomedical Model of Health [18].

While playing a pivotal role in managing illness, effective self-care, in the form of ceasing unhealthy behaviours such as smoking, drinking, and drug-use amongst other things, can also enhance preventative healthcare. Patient self-care improves health outcomes by increasing adherence to therapeutic regimens, encouraging the upholding of healthy behaviours, facilitating the self-appraisal of symptoms in order to start appropriate treatments, and monitoring emotional consequences of illness [19]. Commonly, people resort to employing self-care methods when they develop perceived minor symptoms, which they believe are not worthy of medical attention [20].

During a clinical visit, I met a woman who had recently given birth and believed that her postpartum depression was not worthy of medical attention because she felt that her negative thoughts were not of great importance. Thus, she resorted to talking to friends about it, taking walks, and self-managing her low mood till she felt better again. This reflects how individual perspectives on health can impact someone’s health – seeking behaviour.

Before consulting healthcare professionals, people tend to self–assess their symptoms and seek the advice of the people around them (their lay referral system). Self–curing methods may also be employed, resulting in only a fraction of people with symptoms, presenting to doctors [21]. This ideology can be understood using the iceberg theory of illness, which formulates a relationship between clinical-based epidemiology, or the patients who seek medical help for their symptoms, and population-based epidemiology, or the larger group of symptomatic patients who let their symptoms go unchecked [22]. Knowing the reason why individuals seek medical help, be it their perceived closeness with their physician, their preference for certain consultation approaches, or the aforementioned health beliefs, is essential in modifying the types of health services offered to the public, so that resources are used effectively, and appropriate care is delivered.

Consultation

There has been an evolution in the style of doctor – patient consultations over the years. Arguably one of the most important diagnostic features of consultation is the medical history where the doctor has a concurrent opportunity to establish a rapport with the patient. Physicians who elicit trusting relationships with their patients increase the likelihood of them being more forthcoming and honest, which will improve the effectiveness of care delivered. Due to the central role doctors play in many life-altering moments in a patient’s life, their duty undeniably has a moral component. Ideally, during their career, doctors should attempt to increase the “A” overlap seen in (Figure 4). This is achieved by prioritizing and acting in their patients’ best interests [23]. The General Medical Council (GMC) states that the duties of doctors in the workplace are as follows [24].

i. Interacting with healthcare colleagues in order to maintain and advance quality and safety of patient care.

ii. Participate in discussions pertaining to increasing the quality of services and outcomes.

iii. Act on concerns pertaining to patient safety.

iv. Exhibit capacity for team-working and leadership

v. Advocate for a discrimination-free work environment, understanding that colleagues and patients belong to diverse backgrounds.

vi. Partake in teaching and advising fellow healthcare professionals and being a good role model.

vii. Utilizing resources in order to benefit patients and the public.

Employing methods of standardization within evidencebased medicine in order to reduce costs and ‘save time’, could potentially threaten the delivery of care tailored to patients. This is because their individual characteristics and personal preferences would be disregarded, compromising patient-centred care by making it more disease-centred. Standardization of care would ultimately lead to the doctor-patient relationship being hindered [24]. Stewart et al describes the patient’s perspective of what is expected from patient – centred medicine as [25]:

i. Exploring the main reason of the patient’s visit, their concerns and need for information.

ii. Understanding the patient as a whole person, including their biological, psychological, and social aspects.

iii. Mutually agreeing on a treatment approach for the presenting complaint.

iv. A greater role in prevention and health promotion.

v. Strategies that enhance the relationship between the patient and doctor.

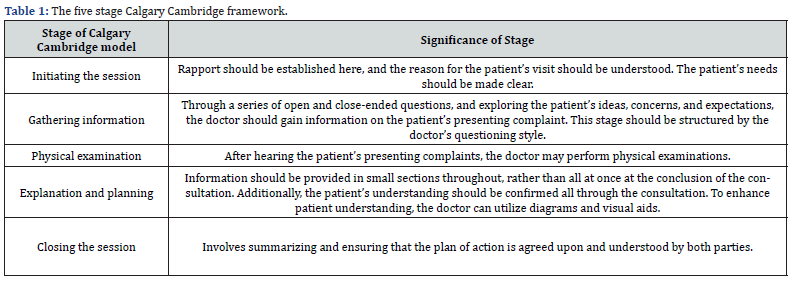

The Calgary Cambridge framework is a tool that has been used to enhance patient centred medicine. It is a five-stage model, demonstrated in (Table 1) [26], which assesses the patient as a whole person, considering their physical, psychological, and social aspects. The Calgary Cambridge framework relies on shared decision making in order to work effectively. Shared decisions increase the likelihood of patient compliance to the recommended plan of action. It is a process in which physicians collaborate with patients to help them make evidence-based decisions that align with their values [27].

Evidence based decisions are made in healthcare systems running on Evidence Based Practise (EBP). EBP is defined as “the conscientious and judicious use of current best evidence in conjunction with clinical expertise and patient values to guide healthcare decisions” [28]. A physician’s clinical expertise is highlighted in their clinical reasoning (CR) skills. CR is the higher level of thinking needed to understand patient problems, assess evidence, and finalize on decisions and choices that will enhance the patient’s physiological and psycho-social outcomes [29]. The clinical expertise of physicians can often be undermined by clinical uncertainty, which is when physicians order excessive investigations, or refer their patients to other practitioners when they come across a presentation, they are unsure of. For doctors to be able to minimize uncertainty and be good at acknowledging it, they need to be skillful in both the science and art of medicine [30].

Another facet of healthcare consultations is health promotion. WHO describes health promotion as empowering people to improve the control they have over their health, with the objective of reducing burden of disease and risk factors [31]. It encompasses social and environmental tools that can be used to protect and better an individual’s health and quality of life by focusing on the causes of the problem, instead of solely on the treatments. The risk factors that can be targeted by physicians during health promotion are not solely biological, but also psychological and social, reaffirming the multifaceted nature of health [32]. Health promotion can be viewed through the lens of different models. The medical model of health sees it as a means of lowering levels of disease and injury in society. The functional model sees it as a way to improve the capacity for people to function in their roles in society, while the idealist view suggests that health promotion will optimize people’s social, physical and mental wellbeing [33].

Health promotion goes hand in hand with disease prevention, as the former being done effectively, cascades into the latter being achieved. Primary disease prevention aims at avoiding the manifestations of a disease, while secondary disease prevention implements early screening in order to improve health outcomes. Early screening alone, however, might not be beneficial if accompanying health issues are not given immediate medical attention [31]. When done efficaciously, health promotion and disease prevention have the capacity to prevent the development of diseases, improve patient quality of life, and save healthcare resources and costs.

Pathways of care and multidisciplinary teamwork

Individuals who are present at healthcare facilities seeking medical advice will, most likely, experience a care pathway. A care pathway is a complex interaction between healthcare workers, enabling the formulation of healthcare plans for groups of patients with predictable clinical courses. Each member of the team has a specific role which is well defined and sequenced, with the ultimate goal being efficacious and suitable delivery of care to the patient [34,35]. The sequence of the care pathway experienced by a patient, is dependent on their presenting complaint, its severity, and the patient’s social standing amongst other factors. The severity of a patient’s illness will determine whether they will receive primary, secondary, tertiary, or quaternary care.

According to the WHO, primary health care (PHC) is crucial as it is often the first point of reference for individuals -especially vulnerable groups who are seeking healthcare. Furthermore, it serves as the bridging point for the other levels of care, as well as for other healthcare specialties. Primary health care teams (PHCTs) - an example of a multidisciplinary team (MDT), may be composed of doctors, nurses, and pharmacists [36]. Each professional in the MDT will contribute from their own specific set of knowledge and skills, which collectively can be used to manage complex health conditions. MDTs regularly meet to discuss the progress of the patient, and to develop treatment plans catered to individual patients [37]. Although GPs are often acknowledged as playing the most pivotal role in PHCTs, the involvement of their counterparts is integral in delivering optimal patient care.

The effective functioning of an MDT relies largely on good communication. The concept of a MDT requires the deconstruction of any communication barriers that may be present between specialists. Additionally, it merges PHC and specialist services which smoothens the transition between the two, allowing patients to receive the care they require with ease. Good communication between healthcare professionals allows the ideas and concerns of patients to be integrated into their care, which consequently increases their compliance and satisfaction. Furthermore, effective communication between patients and members of MDTs has been shown to minimize adverse outcomes and improve health outcomes [38].

Conclusion

Understanding patients as people first and foremost is pivotal in delivering them the necessary care they require. When patients’ ideas and concerns are incorporated into their care, and they are involved in decision making, their compliance to the suggested management improves, which consequently improves their health outcomes. It is the duty of health care providers to be aware of health inequalities and their contributors, and work to minimize them within our own capacities. The real patients interviewed for this paper were from the Malaysian healthcare context and so, patient health beliefs and outlooks may vary depending on the region of the world.

References

- Gatchel RJ, Howard KJ (2021) The Biopsychosocial Approach. Practical Pain Management.

- Cormack B (2019) Have we ballsed up the BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL model?. Cor Kinetic.

- Borrell Carrio F, L Suchman A, M Epstein R (2004) The Biopsychosocial Model 25 Years Later: Principles, Practice, and Scientific Inquiry. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2(6): 576–582.

- Borrell Carrio F. The Biopsychosocial Model 25 Years Later: Principles, Practice, and Scientific Inquiry. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2(6): 576–582.

- Catalyst NEJM (2017) What is Patient-Centred Care?. NEJM Catalyst.

- Salamonsen A (2013) Doctor-patient communication and cancer patients’ choice of alternative therapies as supplement or alternative to conventional care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 27(1): 70–76.

- What are health inequalities?. (2019) NHS Health Scotland.

- Scrambler G (2019) Sociology, Social Class, Health Inequalities, and the Avoidance of "Classism". Frontiers.

- Barry AM, Yuill C (2016) Understanding the sociology of health (5): 57-77.

- Senior M, Viveash B (1998) Health and illness 2: 3-6.

- (2019) Behavioral Change Models. The Health Belief Model.

- Abraham Charles, Sheeran Paschal (2015) The Health Belief Model.

- Jones CL, Jensen JD, Scherr CL, Brown NR, Christy K, et al. (2014) The Health Belief Model as an Explanatory Framework in Communication Research: Exploring Parallel, Serial, and Moderated Mediation. Health Communication 30(6): 566–576.

- Punamaki RL, Kokko SJ (1995) Reasons for consultation and explanations of illness among Finnish primary-care patients. Sociology of Health and Illness 17(1): 42–64.

- Yuill C, Crinson I, Duncan E (2010) The Biomedical Model of Health. Key Concepts in Health Studies, p. 7–10.

- Wade DT, Halligan PW (2004) Do biomedical models of illness make for good healthcare systems?. British Medical Journal. 329(7479): 1398–1401.

- (2018) Biomedical and Social Models of Health. UKEssays.com.

- Greaves CJ, Campbell JL (2007) Supporting self-care in general practice. British Journal of General Practise 57(543): 814–821.

- Braunack Mayer A, Avery JC (2009) Before the consultation: why people do (or do not) go to the doctor. British Journal of General Practice. 59(564): 478–479.

- Collins C, Rochfort A (2016) Promoting Self-Management and Patient Empowerment in Primary Care. Primary Care in Practice - Integration is Needed.

- Last JM (2013) Commentary: The iceberg revisited. International Journal of Epidemiology 42(6): 1613–1615.

- Goold SD Lipkin M (1999) The doctor-patient relationship: challenges, opportunities, and strategies. Journal of General Internal Medicine 14(S1).

- Duties of a doctor in the workplace. GMC.

- MA Stewart, Brown J, Donner A, Mc Whinney I Oates J, Weston, et al. (2000) The Impact of Patient-Centered Care on Outcomes. The Journal of family practice 49: (796-804).

- Denness C (2013) What are consultation models for? InnovAiT: Education and inspiration for general practice. 6(9): 592–599.

- Grad R, Légaré F, Bell NR, et al. (2017) Shared decision making in preventive health care: What it is; what it is not. Canadian Family Physician. 63(9): 682–684.

- Titler MG, Hughes RG Edt (2008) The Evidence for Evidence-Based Practice Implementation. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses.

- Lateef F (2018) Clinical Reasoning: The Core of Medical Education and Practice. Internal Journal of Internal and Emergency Medicine. 1(2): 1015.

- (2010) Uncertainty in medicine. The Lancet. 375(9727): 1666.

- (2020) Health promotion and disease prevention through population-based interventions, including action to address social determinants and health inequity. World Health Organization.

- Kumar S, Preetha G (2012) Health promotion: An effective tool for global health. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 37(1): 5-12.

- Russell A (2009) Lecture notes: the social basis of medicine. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, England.

- Rosique R (2020) Care Pathways: The basics: Healthcare Management. Asian Hospital & Healthcare Management.

- Du S, Cao Y, Zhou T, Setiawan A, Thandar M, et al. (2019) The knowledge, ability, and skills of primary health care providers in SEANERN countries: a multi-national cross-sectional study. BMC Health Services Research 19(1).

- Torrey T (2019) How the 4 Levels of Medical Care Differ. Verywell Health.

- Rice I. What is a Multidisciplinary Team?. The College of Psychiatrists of Ireland.

- Schrijvers G, Hoorn AV, Huiskes N (2012) The Care Pathway Concept: concepts and theories: an introduction. International Journal of Integrated Care 12(6).

- Epstein N (2014) Multidisciplinary in-hospital teams improve patient outcomes: A review. Surgical Neurology International 5(S8): S295-S303.