Exercise Professionals’ Knowledge and Understanding of Eating Disorders and Excessive Exercise

Psillakis E1, Hamann M2, Mond J3, Monzon BM2, Miskovic-Wheatley J2, Maloney D2 and Maguire S2*

1Brazengrowth, Australia

2InsideOut Institute, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Australia

3Western Sydney University (School of Medicine) and University of Tasmania, Australia

Submission: August 12, 2021; Published: August 31, 2021

*Corresponding author: Sarah Maguire, InsideOut Institute, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Australia

How to cite this article: Psillakis E, Hamann M, Mond J, Monzon BM, Miskovic-Wheatley J, Maloney D2 and Maguire S. Exercise Professionals’ 00152 Knowledge and Understanding of Eating Disorders and Excessive Exercise. JOJ Pub Health. 2021; 6(1): 555678. DOI: 10.19080/JOJPH.2021.05.555678

Abstract

Background: Eating Disorders (ED) are complex mental health problems requiring early recognition and treatment. Exercise Professionals (EP) are in close contact with people who suffer from ED and/or Excessive Exercise (EE) and play a role in early intervention and ensuring safe behaviors. We examined the ability of EP to identify eating and exercise issues and to intervene if appropriate.

Methods: Participants were recruited via anonymous online survey advertised through industry channels. A chi-square test of independence examined the associations between socio-demographic characteristics and responses to specific questions (significance level alpha=0.05).

Results: Of 414 respondents, 80.4% were female, mean age 44.8 years, with 13.3 years’ work experience in the fitness sector. More than half (57.2%) did not receive any ED/EE instruction during training and the vast majority (93.0%) indicated a need of further ED/ EE education. While more than three quarters (76.3%) of respondents had suspected an ED/EE in a client, only 25.1% felt confident to address the client about this matter. Approximately one third (30.7%) of respondents reported having a personal experience of an ED and/or EE.

Conclusions: These results highlight a need for better education concerning ED and EE among EP to facilitate early identification and safe industry practice.

Keywords: Eating disorders; Excessive exercise; Fitness industry; Exercise professionals; State of knowledge

Introduction

Exercise is an important component of good health. Under certain circumstances, however, exercise behaviour may be excessive and harmful to wellbeing [1,2]. Key elements of “excessive exercise” (EE) include the experience of guilt when exercise is postponed or delayed and the pursuit of exercise solely or primarily to influence body weight or shape rather than functional movement [3]. EE is often present among individuals with an eating disorder (ED) such as Anorexia Nervosa (AN), Bulimia Nervosa (BN), and related conditions such as Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) and Muscle Dysmorphia (MD) [4-6]. In this context, exercise can become a means to deal with anxiety about body weight and shape, eating behaviours and negative affect. EE can have physiological consequences, such as immune and endocrine disturbances, along with increased risk of physical injuries, exacerbation of body image concerns, eating-disordered behaviour and general psychological distress [7-10]. A problem for public health efforts seeking to reduce the occurrence and adverse impact of EE is that the line between healthy and unhealthy exercise can be difficult to delineate [3,11]. For individuals working in the fitness industry (Exercise Professionals, EP), this issue is compounded by the fact that exercise regimes and specific diets are often encouraged. Fitness and gym activities have been increasing over the past decade in the Australian population, from 12.6% in 2005-06 to 17.4% in 2013-14. Fitness Australia reports that 18–34-year-old Australians have the highest rates of participation in fitness/gym activities nationwide [12]. Females aged 18-24 have the highest participation followed by females aged 25-34 (32.3% and 25.9% respectively), followed closely by males in the same age brackets (25.5% and 20.5% respectively). These groups correspond with those at high risk for the development of ED (females, 18-34 years) [13,14]. Ensuring that EP have the knowledge and skills to detect early signs of EE and ED and initiate intervention where appropriate, would appear to be a key component of overall efforts to reduce the occurrence and impact of EE, although research to inform how this is best done is limited. A Norwegian study of group fitness instructors [15] examined knowledge and attitudes towards identification of ED and EE and steps to support clients, and a Canadian study of EP [16] examined experiences with clients suspected of having AN. Findings from both studies suggested the need to improve knowledge and training amongst fitness instructors around EE and ED issues, including how best to approach clients they might be concerned about, with industry support. Another Canadian study reported that serious ethical and legal issues had been noted by EP working with people with ED, with industry guidelines and training seen as helpful [17]. To our knowledge, no such research has been conducted in Australia, which is significant with the ever-growing nature of fitness participation across the country [12]. Very little to no education on the identification and management of ED/EE has historically been required for practice as an EP in Australia [18], despite the existence of endorsed industry guidelines in how to manage working with someone with ED and/or ED [19].

An additional concern is that individuals with or at increased risk of EE and/or ED may be over-represented among people who choose to work in physical activity and exercise related fields, and this may compromise their objectivity when it comes to recognizing problematic behaviours among clients. Close to one quarter (23.0%) of nutrition students were found to be at risk of exercise addiction in one Australian study [20] while in another American study, over 80% of tertiary students studying Exercise Science expressed a desire to lose weight themselves [21]. Higher risk of ED among athletes compared to non-athletes is well-established [22]. Improved knowledge and understanding of EE and ED issues, including appropriate communication and referral sources for clients if required, may be particularly important to ensure appropriate intervention. With these considerations in mind, we sought to elucidate key aspects of knowledge and understanding concerning Excessive Exercise and Eating Disorders among individuals currently employed as Exercise Professionals in Australia. It was hoped that the findings would inform the further development of guidelines for fitness industry practice, including appropriate training of EP in the management of EE and ED issues.

Ethics and consent to participate

Bell berry Human Research Ethics Committee provided a counterfactual statement that this study was low risk. Participants of this anonymous online survey gave informed consent by submission of survey responses.

Materials and Methods

Study design and recruitment of participants

Potential participants were approached to complete an anonymous, online survey sent via email to all EP (approx. 10,000) registered with the Australian Fitness Network and to personal trainers employed by Virgin Active (approximately 180) in 2016-2017. Information about the study was provided, along with advice that the survey was anonymous, i.e., that since identifying information would not be collected there would be no way for respondents to be identified. Prior to initiating the survey, participants were asked to confirm that they gave permission for any information that they provided to be used for future research purposes such as conference presentations and/or scientific publications. This activity was initially undertaken as an industry knowledge exercise.

The survey

The survey was developed by a team comprised of medical, research and EP as well as people with a lived experience of EE and ED. The content was informed by previous research in the field of “eating disorders mental health literacy” [23,24] and comprised a total of 27 questions in two parts. The initial questions addressed participants’ socio-demographic characteristics, namely, age, gender, work experience in the fitness industry, current level of fitness qualification and current employment. The second part of the survey addressed participants self-reported state of current knowledge about EE and ED, their interest in learning more about EE and ED, their previous experience, including personal experience, of EE and/or ED, and their perceived capacity for communication related to and confidence in the management of clients with suspected EE and/or ED. The barriers that get in the way of gaining knowledge and implementing procedures about EE and ED were also asked. The answers were single, multiple choice and open-ended format. The estimated duration of survey completion was about 15 minutes.

Data analysis

Data are primarily descriptive and indicate the proportion (%) of participants who gave specific responses to individual survey questions. Where appropriate, associations between socio-demographic characteristics and responses to specific questions were examined by means of chi-square tests, with a significance level (alpha) of 0.05. All data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Version 21.0.

Results

Participant characteristics

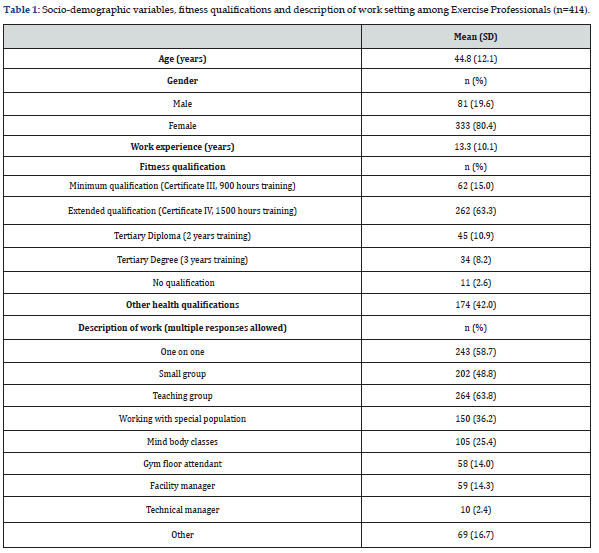

Completed surveys with little or no missing data on key study variables were received from 414 EP aged 18-75 (x̄ = 44.8 years), of whom 80.4% were female. The mean time spent in the fitness industry was 13.3 years (Table I). When compared with data for the fitness industry as a whole (females = 56.0%, x̄ age = 32.0 years), females and older individuals were over-represented among current study participants. Close to two-thirds of participants (63.3%) had a Certificate IV qualification (qualified as a personal trainer, program coordinator and special populations trainer, 1500 hours of training required), 15.0% had a Certificate III qualification (minimum qualification in Australia, qualified to work as gym, group exercise or aqua instructors, 900 hours of training required), with 19.1% having a tertiary qualification and 2.6% having no qualification (i.e. working in other roles within the fitness industry, such as fitness center management or administration). Forty two percent of respondents had other health qualification (instead of or as well as fitness), for example, nutrition, massage, psychology, nursing, or health science.

Current knowledge about eating disorders/excessive exercise

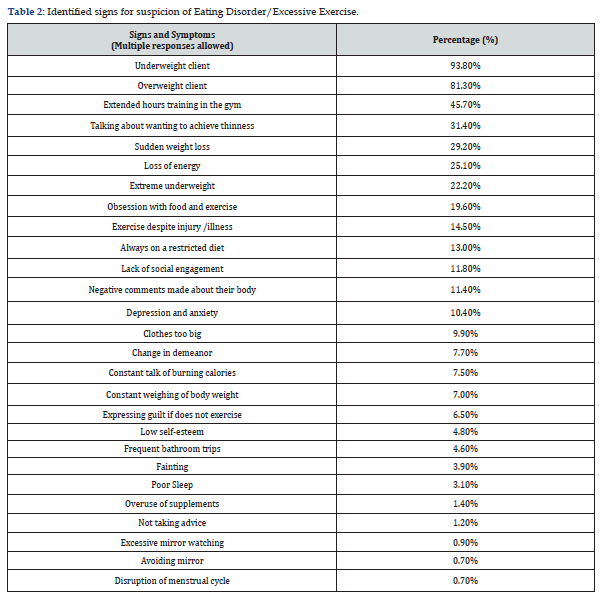

The vast majority of participants reported that they had some knowledge of AN (95.2%), BN (89.3%) and BED (85.2%), while fewer participants reported having knowledge of BDD (63.4%) or MD (38.5%). The signs most often believed to be indicative of an ED or EE were extended amount of time spent exercising and/or multiple exercise sessions on a single day (45.7%) (Table II). Most participants associated having an ED with being underweight (93.8%) or overweight (81.3%), while being normal weight was less likely (51.7%) to be associated with having an ED. There were no other statistically significant associations between EP socio-demographic characteristics and responses to these items.

Education about eating disorder/excessive exercise

A majority of participants (57.2%) did not receive any instructions about ED or EE as part of their fitness qualification, with 23.5% having some form of education external to their fitness qualification. Of the 19.3% who received instruction on ED/EE as part of their fitness qualification, the majority reported receiving only 1-2 hours of education across their total training, regardless of level of training. EP holding a higher qualification (Certificate IV and above) had more knowledge of the role of EE in ED behaviours (63.1%), as compared to only 14.9% of EP with minimum qualifications (Certificate III), although there was no significant difference in specific training hours for this knowledge. Ninety three percent of all respondents felt that EP should be required to learn more about ED/EE in their qualification. The majority of participants (80.1%) believed that learning more about ED and/or EE as part of their training was extremely (41.5%) or very (38.6%) important. A minority of participants (17.0%) reported that they had received further training in ED/EE and of this group, most reported that the additional training was self-directed (78.3%). Lived experience of ED and/or EE was reported by 25.1% of the participants who reported seeking further training in ED/EE. There was a significant association between gender and the belief that education about ED/EE should be required for EP, such that female participants were more likely to believe that additional training should be required than male participants (χ2(1) = 0.025, p<0.05).

Experience with eating disorder/excessive exercise

Most participants (76.3%) had at some time suspected that a client or member in their fitness center was experiencing an ED and/or EE, while 72.2% reported they had observed someone with a possible ED and/or EE problem within their professional practice. Further, participants who reported having suspected ED and/or EE among clients (80.1%) were more likely to endorse the need for EP to have an understanding of ED/EE problems (χ2(3) = 8.913, p<0.05) than those who hadn’t (19.9%). Personal, i.e., lived experience of an ED or EE was reported by close to one third (30.7%) of participants. More than half of this group (55.6%) reported that they had a friend or family member with an ED and/or EE, while 6.3% reported that their partner has had an ED and/or EE. There were no other significant associations between EP socio-demographic characteristics and responses to other survey questions.

Communication and confidence in management of clients with suspected eating disorder/excessive exercise

Most participants (74.9%) reported being only a little or moderately confident in approaching a client to address a possible problem about an ED or EE, or in taking appropriate next steps upon suspecting or discovering that a client had an ED and/or EE issue (74.6%) ([χ2(9) =396.695, p<0.05). The biggest reported barriers to approaching clients suspected of having an ED and/or EE included: insufficient knowledge/education (31.6%), industry focus on body weight/shape and dieting (14.7%), concern about offending a client (14.3%), concern about losing members/clients (8.5%) and the belief that ED/EE are beyond the scope of fitness industry practice (8.5%). Less than one quarter (23.9%) of participants indicated that their membership screening questionnaire including questions related to ED and/or EE. There were no other significant associations between EP socio-demographic characteristics and responses to other survey questions.

Discussion

Main findings of this study

The primary goal of the current research was to determine Exercise Professional’s knowledge and understanding of Eating Disorders and Excessive Exercise issues, particularly in regard to identification and appropriate referral for clients suspected of experiencing, or being at high risk of, these issues. A majority (76.3%) of EP reported having observed someone with a possible problem with ED and/or EE within their practice, which is somewhat higher than the Canadian (62.0%) [16] and Norwegian studies (49.0%) [15]. Despite participants in the current study reporting some knowledge of ED signs and symptoms, the majority (74.9%) were not confident to address or manage a client who they suspected might have an ED. These results are also consistent with findings from other related studies [16-18]. Of note, participants in the current study who reported having a client that they suspected might have an ED and/or EE were more likely to endorse the need for better understanding of ED/EE amongst EP than those who did not (80.1% vs 19.9%). Participants in the current study clearly believed that having an ED is associated with body size. Thus, most participants associated underweight (93.8%) and overweight (81.3%) with an ED while believing that it was far less likely (51.7%) that a normal weight person might have an ED. This is concerning given that many individuals with ED, including many individuals suffering from bulimia nervosa, atypical forms of anorexia nervosa, and variants of these conditions such muscle dysmorphia, fall within the normal body weight range, yet are likely to be employing dangerous methods to control their weight and shape. The need to address these behaviours may not be taken into consideration by the EP if body size is the primary indicator of the ED. Thus, the findings highlight the need for better education of EP concerning the nature and presentation of ED and for the inclusion of routine screening for ED/EE issues by EP and or the fitness center.

What is already known on this topic

Very little education on the identification and management of ED/EE has historically been required for practice as an EP in Australia, despite the existence of endorsed industry guidelines in how to manage working with someone with ED and/or ED [19]. Even though almost half of participants (49.1%) in the current study had more than 10 years of experience in the fitness industry, most (57.2%) reported receiving no education about ED or EE as part of their fitness qualification. In the Canadian study, the proportion who received no ED content in training was higher still (74.3%) [16]. Findings from both studies suggested the need to improve knowledge and training amongst fitness instructors around EE and ED issues. It is also noted that those who work in fitness and health fields may be over-represented by those with a history of eating disorder symptoms [20,21]. Theoretically, this may compromise objectivity in recognizing at risk behaviour in clients, although potential impact requires more investigation.

What this study adds

In the current study, the majority of participants reporting that they had some education relating to ED indicated that they had received approximately 1-2 hours of such training, within a minimum of 900 overall training hours. This is remarkably little education for serious, complex conditions that are relatively common in the fitness setting and so closely intertwined with exercise behaviour. Further, only a minority of participants in the current study (17.0%) reported that they had received further training in ED/EE and of this group, most reported that the additional training entailed self-directed learning (78.3%). These findings suggest considerable unmet need for appropriate training of EP in ED/EE issues across all training levels, which is supported by related research [15-17]. In the current study, the most common barriers to early intervention for ED/EE issues in the fitness setting were reported to be lack of knowledge around how best to do so, and client focus on body shape and size rather than functional movement (the ability to move the body with proper muscle and joint function for effortless, pain-free movement), with the latter a key component of EE [3]. Additional barriers included lack of awareness and education including knowledge of next steps and clinical referrals, protection of client privacy, and fear of offending and losing clients. Because ED and EE are closely associated [25], it is essential to provide knowledge about both conditions for professionals working in the fitness industry, as well as how to make an approach to a client of concern. The finding that close to one third of participants (30.7%) in the current study reported personal experience of an ED and/or EE, consistent with findings from the Norwegian study (29.0%) [15], highlights the fact that improved awareness and understanding of ED and EE issues among EP would likely be beneficial to both clients and to EP themselves. Strengths of the current research include its novelty and the recruitment of a relatively large sample of EP from across Australia and that, to our knowledge, this is the first such study in Australia. We hope that the findings will inform the development of mandatory education modules for the fitness sector that provide education, confidence and skills for EP to work safely with clients, especially those at risk or currently experiencing ED and/or EE, the utility of which could then be empirically tested. Future research could also conduct more intensive investigations of the barriers affecting EP and the industry in reducing ED and EE risk, consequently updating current industry-endorsed guidelines 19 and the translation of such guidelines into training and practice.

Limitations of this study

As in other online surveys of this kind, response rate in the current study was low and the generalizability of the findings may therefore be compromised. Among other potential biases, older individuals and females were over-represented among current study participants when compared with the Australia fitness industry workforce as a whole [26]. The relative paucity of male participants may reflect, in part, the misconception that ED and/or EE are primarily “female” issues [23,24]. Hence, improving awareness and understanding of ED and EE among male EP may be particularly important. Additional limitations of the current study included the use of a cross-sectional study design and the inclusion of a relatively small number of forced-choice, self-report items that may be prone to other biases, such as social desirability.

Conclusion

This study is one of only a handful of studies worldwide to examine knowledge experience, confidence and training about eating disorders and Excessive Exercise within the fitness industry, exposing the need for more education and industry support to ensure safe practice. Both male and female EP are in close contact with clients who might experience an ED and/or EE and may be an important group of professionals to identify and positively contribute to healthy behaviours, and the minimization of unhealthy behaviours. It is also important for EP to understand that ED are not limited to a certain gender, age group or weight class. There is no current mandatory education regarding identifying and supporting clients with or at risk of ED or EE for registered professionals and while self-selected education may indicate an interest in the topic of ED and EE, sufficient mandatory training would ensure that all EP are equipped with the knowledge and appropriate practice to ensure safety of clients with or at risk of developing ED and/or EE. Industry endorsed guidelines for EP in the management of ED and EE when working with these clients are important for setting standards that are industry wide, rather than self-selected. The results of the present study will contribute to the refinement of such Fitness Australia endorsed guidelines [27] and the provision of targeted training [28,29] which aim to give Australian health professionals the knowledge, skills and confidence they need to work with clients at risk of or presently experiencing an Eating Disorder or Excessive Exercise.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their contribution to all fitness professionals (Alisha Smith, Mark Seeto, and Leesa Bloom), Eyza Koreshe for research support, and the lived experience consultants who participated in the development of the survey.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available to be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest pertaining to this study.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript. Conceptualization: EP, JM and SM; methodology: EP, JM, BM, DM, SM; formal analysis: MH, JM; data curation: MH, JM, JMW; writing original draft preparation: EP, MH, JM, BM, DM, SM; writing review and editing: EP, JMW, JM, SM; supervision: JM, SM.

References

- Rhodes RE, Janssen I, Bredin SS, Warburton DE, Bauman A (2017) Physical activity Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychology & Health 32: 942-975.

- White RL, Babic MJ, Parker PD, Lubans DR, Astell Burt T, et al. (2017) Domain specific physical activity and mental health: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 52: 653-666.

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C (2006) An update on the definition of excessive exercise in eating disorders research. International Journal of Eating Disorders 39: 147-153.

- Mond JM (2013) Classification of bulimic type eating disorders from DSM-IV to DSM-V. Journal of Eating Disorders 1: 33.

- Mitchison D, Mond JM (2015) Epidemiology of eating disorders, eating disordered behaviour, and body image disturbance in males: A narrative review. Journal of Eating Disorders 3: 20.

- (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (DSM-5®), American Psychiatric Association.

- Adams J, Kirkby R (2001) Exercise dependence and overtraining: The physiological and psychological consequences of excessive exercise. Sports Medicine training and rehabilitation 10: 199-222.

- Paradis KF, Cooke LM, Martin LJ, Hall CR (2013) Too much of a good thing? Examining the relationship between passion for exercise and exercise dependence. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 14: 493-500.

- Cook B, Hausenblas H, Crosby RD, Cao L, Wonderlich SA (2015) Exercise dependence as a mediator of the exercise and eating disorders relationship: A pilot study. Eating behaviors 16: 9-12.

- Shroff H, Reba L, Thornton LM, Tozzi F, Klump KL, et al. (2006) Features associated with excessive exercise in women with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders 39: 454-461.

- De La Cruz D (2018) Gyms are in a position to spot eating disorders but actually helping is tricky.

- (2016) Profile of the Fitness Industry in Australia: Fitness Industry Consumers. Fitness Australia.

- Johnson CS, Bedford J (2004) Eating attitudes across age and gender groups A Canadian study. Eating and Weight Disorders Studies on Anorexia Bulimia and Obesity 9: 16-23.

- Hay P, Girosi F, Mond JM (2015) Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in the South Australian Community. Journal of Eating Disorders 3: 19.

- Bratland Sanda S, Sundgot Borgen J (2015) I'm concerned What Do I Do? recognition and management of disordered eating in fitness center settings. International Journal of Eating Disorders 48: 415-423.

- Wojtowicz AE, Alberga AS, Parsons CG, Von Ranson KM (2015) Perspectives of Canadian fitness professionals on exercise and possible anorexia nervosa. Journal of Eating Disorders 3: 40.

- Manley RS, O Brien KM, Samuels S Fitness (2008) Fitness instructors’ recognition of eating disorders and attendant ethical/liability issues. Eating Disorders 16: 103-116.

- (2019) Qualification Details SIS40215 Certificate IV in Fitness. Training.Gov.Au.

- Marks P, Harding M (2004) Fitness Australia Guidelines Identifying and managing members with eating disorders and/or problems with excessive exercise. A collaborative project between The Centre for Eating & Dieting Disorders [CEDD] and Fitness First Australia on behalf of Fitness Australia Sydney.

- Rocks T, Pelly F, Slater G, Martin LA (2017) Prevalence of exercise addiction symptomology and disordered eating in Australian students studying nutrition and dietetics. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 117: 1628-1636.

- Harris N, Gee D, d’Acquisto D, Ogan D, Pritchett K (2015) Eating disorder risk exercise dependence and body weight dissatisfaction among female nutrition and exercise science university majors. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 4: 206-209.

- Thiemann P, Legenbauer T, Vocks S, Platen P, Auyeung B, et al. (2015) Eating disorders and their putative risk factors among female German professional athletes. European Eating Disorders Review 23: 269-276.

- Mond JM (2014) Eating disorders mental health literacy An introduction. Journal of Mental Health 23: 51-54.

- Bullivant B, Rhydderch S, Griffiths S, Mitchison D, Mond JM Eating Disorders Mental Health Literacy A Scoping Review. Journal of Mental Health (in press).

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont P (2004) Relationships between exercise behaviour eating disordered behaviour and quality of life in a community sample of women when is exercise ‘excessive’?. European Eating Disorders Review 12: 265-272.

- (2016) Profile of the Fitness Industry in Australia Fitness Industry Workforce. Fitness Australia.

- (2019) Fitness Australia Eating Disorders: Recommendations for the Fitness Industry. Inside Out Institute.

- Supporting clients at risk of Eating Disorders Course. Brazen growth.

- (2019) Supporting clients at risk of eating disorders. Inside Out Institute for Eating Disorders.