Nutritional Status of Reproductive Aged Santal Ethnic Women

Faroque Md Mohsin

Master of Public Health, North South University, Bangladesh

Submission: April 16, 2019; Published: May 29, 2019

*Corresponding author: Faroque Md Mohsin, Master of Public Health, North South University, Bangladesh

How to cite this article:Faroque Md Mohsin. Nutritional Status of Reproductive Aged Santal Ethnic Women. JOJ Pub Health. 2019; 4(3): 555643. DOI: 10.19080/JOJPH.2019.04.555643

Abstract

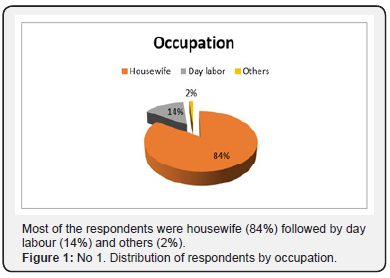

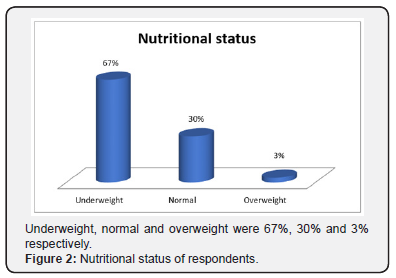

Measurement of nutritional status is always vital and thought to be primary step to formulate development strategy. Reproductive aged ethnic women are important group to study because of their distinct features. An observational cross-sectional study was carried out at northern part of Bangladesh to assess nutritional status of reproductive aged Santal women with a sample size 200. Face to face interview was carried out with the semi-structured questionnaire. Convenient sampling technique was used to collect data on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria and written consent was taken prior to interview. Nutritional status was determined according to BMI cut off value for Asian population.Descriptive as well as inferential statistics were used to present data. Mean±SD age of respondents was 34.27±8.60. More than half (67%) of the respondents were illiterate and housewife (84%). Mean±SD income of respondents was 5700.71±282.89 per month. Underweight, normal and overweight were 67%, 30% and 3% respectively. Most respondents took rice 2-3times/day. Vegetables and soya bean were taken randomly. Lentil was taken daily. Statistical significant association was found between nutritional status and age group (p<0.05), education (p<0.05), occupation (p<0.05) and monthly income (p≤0.05). Half of the respondents suffered from underweight and most of them income was very low. Income generating capacity should be increased as well effective nutrition education programme must be instituted.

Keywords:Discretionary; Nutrition Education; Malnutrition; Productive; Mortality; Non-Reproductive; Food Price-Hike; Household Management; Food Preparation; Cleaning Duties

Introduction

Reproductive health is closely related with nutritional status of a country. The biologic and socio-economic differences between women and men sometimes place women at higher risk for malnutrition and mortality. In some countries, girls are treated differently in terms of access to health care, food, and education [1]. Nutritional problems are different between developed and developing countries. Bangladesh is placed in the bottom 25% of the Global Hunger Index ranking, indicating that the country is expected to face a huge risk in the context of food price-hike [2]. The social roles of women generally include major responsibility within the household of care for the other members, involving household management, food preparation, cleaning duties, obtaining health care, education and supervision of children. In addition to this family role, they frequently have kin and community roles and finally, “productive” income-producing as well as non-income producing roles in agriculture, the marketplace, home production, factory or other work activities.

The extent and nature of the specific set of roles for any given woman at any particular point in her life is highly variable, but in all cases biological reproductive roles are undeniable (although in rare circumstances they can be avoided) and in the overwhelming number of cases the household responsibilities lie within the woman’s basal set of tasks. Time allocation studies have shown repeatedly that the woman’s workday is longer than a man. Women have less “leisure” or “discretionary” time available than men. Girls frequently spend more time in household maintenance activities than boys. The long hours and multiple roles of women create a “social vulnerability” to problems of malnutrition particularly during the reproductive years.

Time constraints may lead to infrequent meals and exhaustion may lead to a reduced appetite, and lower overall intake results in lower intake of individual nutrients. Given the long hours worked and multiple roles frequently fulfilled by women in settings of poverty, they are at risk for general under nutrition. Maternal nutritional status is important for a host of reasons for the woman herself, for her capacity to reproduce, and for the development of her children, with implications for the health and reproductive capacity of the next generation’s mothers. Pregnant women with a low BMI are at a greater risk for preterm delivery, low birth weight, and fetal growth restrictions [3]. The Santals form the largest tribal community in northern Bangladesh. Most of the Santal villages are in remote places. Scarcity of information and diverse lifestyle makes them an important area of research.

Methods and Materials

It was a cross-sectional study. The study was conducted among reproductive age Santal women residing in Thakurgaon and Dinajpur district. This study was conducted for a period of six month. The sample size was three hundred and fortyfive, for the time and economical constraints it was taken as 200. All reproductive aged women and willing to participate were included in the study. Non reproductive aged women and not willing to participate were excluded. Nonprobability convenient sampling technique was applied. Data were collected by pretested semi structured questionnaires and in face to face interview. Information about nutritional status along with sociodemographic characteristics was also obtained. The respondents were selected consecutively who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Nutritional status was determined by body mass index according to WHO cut off value i.e. <18.50 = underweight, 18.50-22.99=normal, 25-26.99=overweight and ≥27=obese. Consent was taken from every individual who was the part of the study. Confidentiality of the person and the information was maintained, observed and unauthorized persons did not access to the data. Each subject was assigned a study identification number and these subject identifiers did not release outside the authorized person.

Results

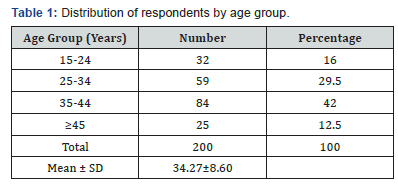

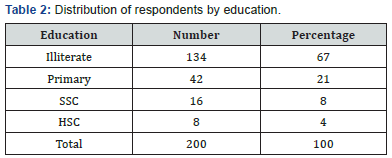

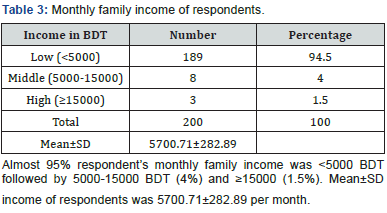

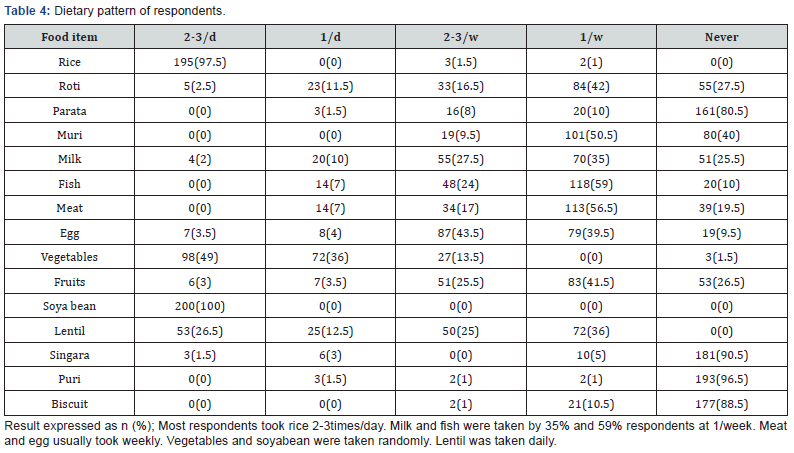

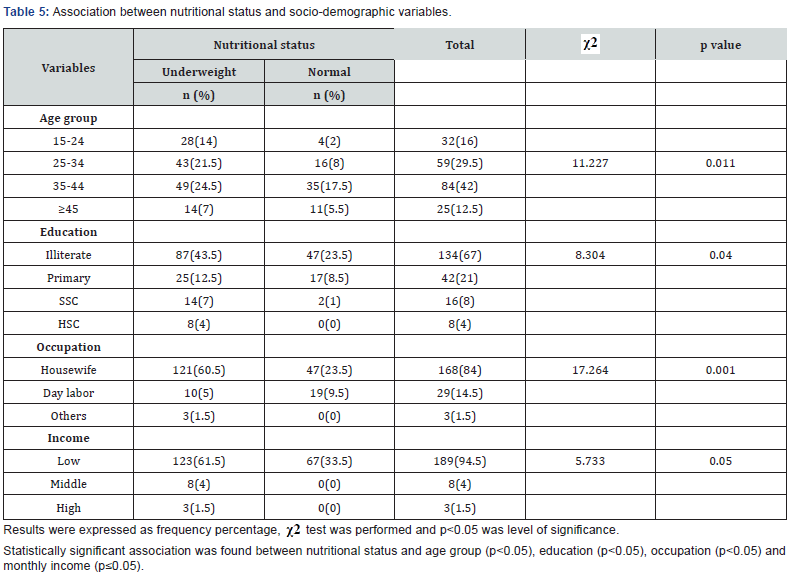

(Table 1) shows that 42% of the respondents was in age group 35-44 years and 29.5%, 16% and 12.5% was in 25-34, 15- 24 years and ≥45years with mean age 34.27±8.60 years. (Table 2) More than half (67%) of the respondents were illiterate followed by primary (21%), SSC (8%) and HSC (4%). (Figure1) Most of the respondents were housewife (84%) followed by day labor (14%) and others (2%). Table 3 shows almost 95% respondents monthly family income was <5000 BDT followed by 5000-15000 BDT (4%) and ≥15000 (1.5%). Mean ± SD income of respondents was 5700.71±282.89 per month. (Figure 2) Underweight, normal and overweight were 67%, 30% and 3% respectively. (Table 4) Most respondents took rice 2-3times/ day. Milk and fish were taken by 35% and 59% respondents at 1/week. Meat and egg usually took weekly. Vegetables and soya bean were taken randomly. Lentil was taken daily. (Table 5) Results were expressed as frequency percentage, test was performed and p<0.05 was level of significance. Statistically significant association was found between nutritional status and age group (p<0.05), education (p<0.05), occupation (p<0.05) and monthly income (p≤0.05).

Discussion

Diet and nutrition are important factors in the promotion and maintenance of good health throughout the life cycle. Income, prices, individual preferences and beliefs, cultural traditions, as well as geographical, environmental, social and economic factors all interact in a complex manner to shape dietary consumption patterns and affect the morbidity and clinical status of women. A normal balanced diet must include daily foods from the various food groups in sufficient amounts to meet the needs of an individual and to increase immunity. The present study found gloomy picture of nutritional status of reproductive aged Santal women. More than half of the respondents were suffering from underweight which is a threat for good health. Similar findings have also been presented in a study conducted on diet and nutritional status of women by Mallikarjuna Rao et al. [4]. Their study revealed that the intake of all the foods except for other vegetables and roots and tubers was lower than the suggested level among rural as well as tribal women.

The study revealed inadequate dietary intake, especially micronutrient deficiency (hidden hunger) during reproductive years. The study showed that the intake of cereals and millets was 402 g and 365 g, respectively in tribal and rural NPNL women. Except for other vegetables and roots and tubers, the intake of all the other foods was lower than the suggested level in both rural and tribal areas. The intake of income elastic foods such as milk, oils and fats were higher in rural than in tribal NPNL. The intakes of all the nutrients were lower than the recommended levels suggested by ICMR in all the physiological groups in both the areas. The deficit was more with respect to micronutrients such as iron, vitamin A, riboflavin and free folic acid.63 Most respondents took rice 2-3times/day. Milk and fish were taken by 20 and 40 respondents at 2-3times/day. Meat and egg usually took weekly. Vegetables and soya bean were taken randomly. Lentil was taken daily. Regarding nutritional deficiency, about half of the rural women (52%) had some form of signs relating to vitamin A deficiency and 65% had signs of vitamin B complex deficiency either in the form of glossitis or of angular stomatitis or both.64 Our study got arthritis, headache, skin disease was more common. In case of appetite 66% of respondents had good appetite. About one-third of study subjects had sleep disturbance, anxiety as well as depression. A study conducted on health problems of rural women indicated the prevalence of a number of health problems among rural women and a need for their education on health aspects [5]. A multivariate analysis shows association between malnutrition and monthly household income, history of taking oral contraceptive, current pregnancy status, and history of breastfeeding.

The final regression model shows a statistically significant decreasing trend in malnutrition status with increasing income (p<0.001). The economic and health consequences of malnutrition in this group of women are enormous. National nutritional program should target this women group for any intervention with a special priority [6]. A cross sectional study was done in the purposively selected Panchari thana of Khagrachari district in Bangladesh. A total of 200 reproductive aged women were interviewed. Among them 100 were indigenous and 100 were settlers. Their anthropometric measurements were taken, and nutritional status was determined by body mass index (BMI) recommended by World Health Organization (WHO) for Asian people. Among the indigenous subjects Chakma, Marma, Tripura and Boisnu were 20.5%, 20.5%, 6.5% and 2.5% respectively. Among 100 indigenous reproductive aged women 17 were underweight; but among settlers 19 were underweight. Forty-nine settler women were normal and in case of indigenous women 46 were normal. But regarding overweight indigenous women went ahead than settler women and obesity was found equal in both groups [7].

Conclusion

It is concluded from the study that more than half of the reproductive aged Santal women suffered from underweight. Besides most of them were poor. Majority of them were illiterate too. Rice, vegetables and lentil were common food. Milk, egg, meat was seldom taken. Underweight was more seen among illiterate, low income and housewife and it was statistically significant.

References

- United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination/Sub-Committee on Nutrition (1992) Second report on the world nutrition situation. Vol I: Global and regional results. ACC/SCN, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Ahmed T, Mahfuz M, Ireen S, Ahmed AM, Rahman S, et al. (2012) Nutrition of Children and Women in Bangladesh: Trends and Directions for the Future. J Health Popul Nutr 30(1): 1–11.

- Blössner M, De Onis M (2005) Malnutrition: Quantifying the health impact at national and local levels. World Health Organization WHO Environmental Burden of Disease, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Mallikharjuna, Balakrishna et al. (2010) NIN, ICMR: diet and nutritional status of women in India. J Hum E col 29(3): 165-170.

- Sharma and Saroj D (1989) Health and population - perspectives & issues. Journal of Population Research 9(1): 18-25.

- Milton AH, Smith W, Rahman B, Ahmed B, Shahidullah SM (2010) Prevalence and determinants of malnutrition among reproductive aged women of rural Bangladesh. Asia Pac J Public Health 22(1):110-117.

- Haque et al. (2014) Nutritional Status of Settler and Indigenous Women of Reproductive Age Group in Khagrachari District, Bangladesh. J Enam Med Col 4(2): 98-101.