The Accessibility of Australia’s Rural and Remote Population Centres to Outpatient Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs

Deborah van Gaans*

The University of Adelaide, Australia

Submission: February 08, 2019; Published: April 02, 2019

*Corresponding author: Deborah van Gaans, The University of Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

How to cite this article:Deborah van Gaans. The Accessibility of Australia’s Rural and Remote Population Centres to Outpatient Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs. JOJ Pub Health. 2019; 4(3): 555639. DOI: 10.19080/JOJPH.2018.04.555639

Abstract

Accessibility is a major factor in the underutilisation of Outpatient Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs within Australia. Previous studies on accessibility to cardiac services have been based on travel time, cost or distance only, and provide only a partial view of access to services. The Spatial Model of Accessibility to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation was used to measure the socio-economic and geographical accessibility of Australia’s Phase 2 (outpatient) cardiac rehabilitation programs. Rural and remote population centres were defined using the Accessibility / Remoteness Index for Australia (ARIA). The Spatial Model of Accessibility to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation has been used to identify areas where accessibility to these programs could be improved and where new programs or models of delivery should be established to enhance accessibility in areas that are currently poorly served. This research has identified that there is a need for better service planning aimed at increasing the accessibility to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs within Australia. The factors affecting the accessibility of at-risk populations should be considered and the current services should be improved to meet the specific needs of the population that they could service.

Keywords:Accessibility; Equity; Cardiac Rehabilitation; Spatial Analysis; Geographic Information Systems; Health Service

Abbreviations: SES: socioeconomic status; GIS: Geographic information systems

Introduction

Compared with their urban counter parts, rural and remote people experience poorer health as evidenced by higher mortality, lower life expectancy and an increase in incidence of some diseases [1]. Therefore, optimal provision of health and human services to residents of low socioeconomic status (SES) suburbs is particularly important, given the substantial evidence of the relationship between low SES and poor health in Australia [2]. The major issues for remote populations relate to access to services rather than health differentials [3]. Key findings by Savage et al. [2] indicate that successful navigation of health care services by residents within these low socioeconomic status (SES) environments is being impeded by issues of access, a lack of appropriate early intervention options or measures, and general resident disempowerment. Rowland & Lyons [4] found that residents in rural areas were more likely to be poor and uninsured. Coupled with the reduced availability of health services in rural areas, rural residents receive fewer physician and hospital services than urban residents [5]. However, access to health care is perceived to be an important factor that contributes to improved health status [1].

Access problems are particularly acute for families living in those small rural communities which have borne the brunt of recent withdrawal and rationalisation of many local health care services undertaken by State Government health authorities [6]. The impact of economic and social changes is creating additional pressures for many rural families [6]. Such pressures exacerbate the existing problems resulting from lack of locally available health care services and difficulties associated with accessing them from distant locations [6]. Eckert et. al. [1] found that there is higher use of primary care services among residents of highly accessible areas, and as remoteness increases the levels of use of public hospitals decreases significantly. The reported higher use of allied health services in moderately accessible areas may be in response to the increasing reliance on complementary and alternative health provider care that has occurred in Australia over the past decade [1]. Without appropriate resources and support to ensure their health care activities are effectively maintained, some families and communities are being placed unnecessarily at risk [6]. The provision of cardiac rehabilitation services to people living in rural and remote areas is often limited to the nearest large hospital situated in urban coastal centres, leaving a gap in the rehabilitation of cardiac patients [7].

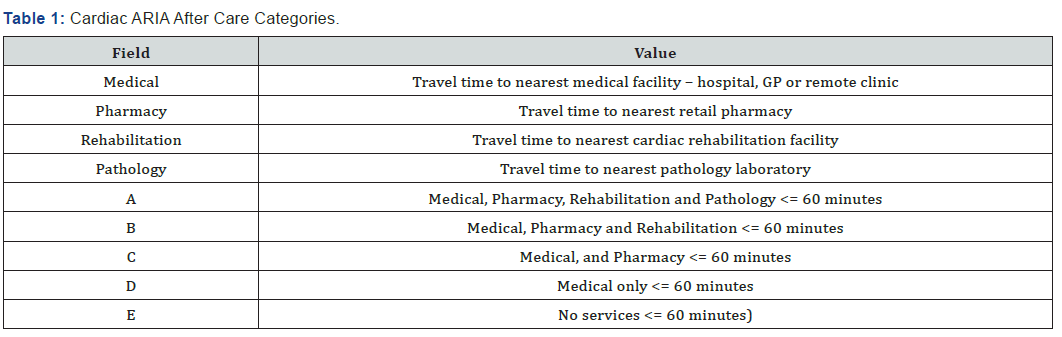

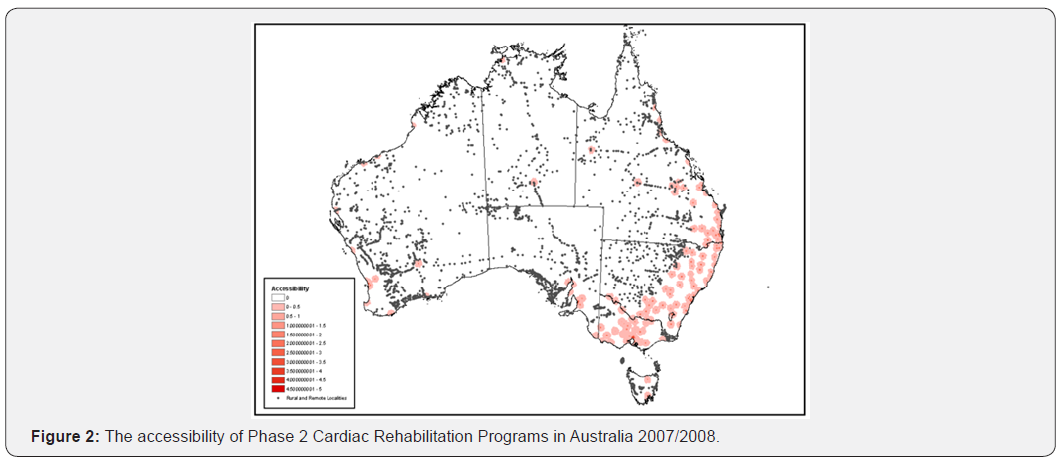

Measuring accessibility to cardiac after care services is critical to identifying gaps in the continuum of care for cardiac patients. With the focus of identifying where access to basic services for secondary prevention is limited in the community Clark et al. [8] developed the Cardiac Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia (Cardiac ARIA). Clark et al. [8] used Geographic information systems (GIS) technology to model the access to four basic services (general practitioner/nurse clinic, pharmacy, cardiac rehabilitation, pathology) within a one-hour drivetime from each of Australia’s 20,387 population locations. The Cardiac ARIA aftercare phase was modelled into five alphabetic categories, A (all four services =1h) to E (no services available within 1h) (Table 1). Time to each of the facilities was calculated based on urban road speeds of 40kph, non-urban road speeds at 80kph, and off-road speeds at 50kph [9].

Clark et al. [8] found that 18% of the population locations were within category “A” zones with the remaining 82% located in zones with some limitation to recommended services. From the location data Clark et al. [8] estimated that 96% or 19 million Australians lived within one hour of the four basic services to support cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention, including 96%>65 years and 75% of the Indigenous population. Therefore, as can be seen in (Figure 1) most Australians had excellent “geographic” access to services after a cardiac event. This research by Clark et al. [9] highlights that further research is needed to identify which aspects of accessibility other than geographic distance to cardiac rehabilitation affect utilisation of services [9].

Thornbill & Stevens [10] found that attendance at cardiac rehabilitation programs in rural and remote areas is greatly affected by geographical position. Ensuring appropriate access to health services in rural and remote areas is more difficult because long-distance travel is often required. Distance is one important factor that has been shown to affect access to, and utilisation of, health services [1]. People from rural and remote areas commonly need to attend large rural towns and metropolitan cities for specialist care [11]. Their decision to make such trips “away” involves a number of non-medical considerations that include economic, emotional and social factors [11]. Thornbill & Stevens [10] found that those who lived close to the cardiac rehabilitation program were more likely to attend compared with those who lived further away. The availability of transport and the cost and time of transport were the leading reasons for non-attendance of a cardiac rehabilitation program [10]. Research by Veich et al. [11] revealed that rural and remote patients made important considerations when planning their trip to an urban facility; they were predominately related to urgency, household organisation and the costs likely to be incurred while away. Generally, remote area respondents saw these impediments as more serious barriers to seeking care than did rural area respondents [11]. The provision of cardiac rehabilitation services to people living in rural and remote areas is often limited to the nearest large hospital situated in urban coastal centres, leaving a gap in the rehabilitation of cardiac patients [7]. Veitch et al. [11] found that rural people encounter problems at urban facilities particularly problems directly related to the lack of understanding of the transport and distance needs of rural people.

Structured Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation provides an opportunity for the development of a life-long approach to prevention and management of cardiac disease for patients. Within the continuum of care for cardiac patients within Australia, the entry into a Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Program after a hospital stay is determined by the patient. Accessibility has been identified as a major factor in the underutilisation of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs both within Australia and internationally. As identified by Clark et al. [8] the majority of Australians have good (less than one hour) geographic accessibility to cardiac rehabilitation, however these services still remain underutilised. Like the research undertaken by Clark et al. [8] previous studies on accessibility to cardiac services have been based on travel time, cost or distance only, and they therefore provide only a partial view of access to services.

In reality, people trade off geographical and nongeographical factors in making decisions about health service use [12]. To gain a better understanding of the accessibility of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs the Spatial Model of Accessibility to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation was developed using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to combine both geographic and socio-economic dimensions of accessibility [13]. The model was based on published literature on the barriers to accessing cardiac rehabilitation and the Penchansky & Thomas [14] dimensions of accessibility which include accessibility, availability, accommodation, affordability, and acceptability.

Method

Spatial modelling

The Spatial Model of Accessibility for Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation [13] was used to collect socio-economic and geographic information on each of Australia’s Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs. The model produced an overall rating of accessibility for each of the Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs across Australia that responded to the survey. This included a rating for the programs; availability, accommodation, affordability and acceptability. Rasters for each of the Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs were created using ESRI ArcGIS version 9.3.1. Each raster was then over layed and ESRI’s Spatial Analyst was used to show the maximum accessibility value for each cell.

Determining the accessibility of rural and remote population centres to phase 2 cardiac rehabilitation programs

Rural and remote localities were defined using ARIA+ scores (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2001). ARIA measures remoteness in terms of access along the road network from 11,340 populated localities to four categories of service centres. Localities that are most remote have least access to service centres; those that are least remote have most access to service centres. ARIA+ scores > 5.92 - 10.53 were used to represent remote Australia where very restricted accessibility of goods, services and opportunities for social interaction exist. ARIA+ scores >10.53 were used to represent very remote Australia where localities are locationally disadvantaged as there is very little accessibility of goods, services and opportunities for social interaction. A surface of accessibility to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs was created and overlaid with the rural and remote population centres. Each rural and remote population centre was then assigned a rating of accessibility to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation.

Results

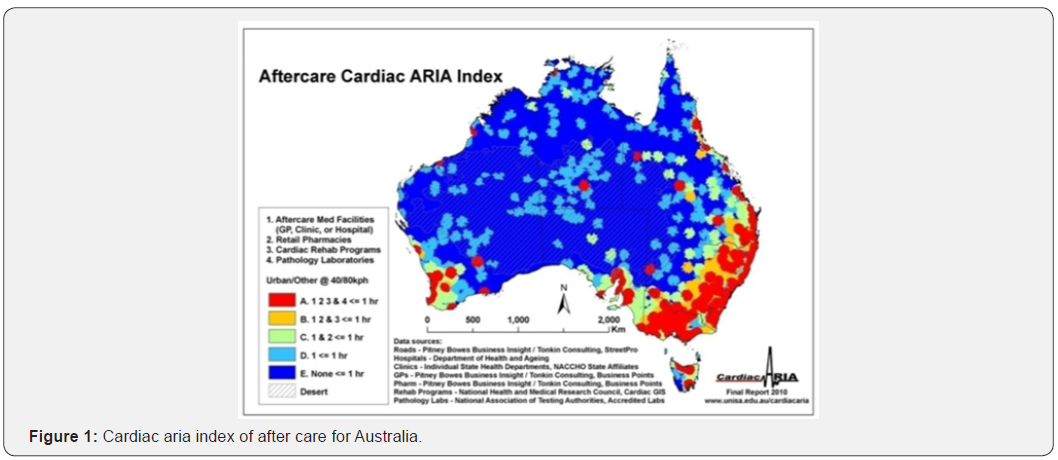

The output from the Spatial Model of Accessibility to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Model [13] against the rural and remote localities, as determined by the Australian Remoteness Index for Australia (ARIA) highlight that the accessibility of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs in 2007/08 was extremely variable across Australia. Figure 2 shows that much of central and north Queensland, western New South Wales, north eastern Victoria, and all almost all non-metropolitan areas of the Northern Territory, South Australia, Tasmania and Western Australia had no access to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs. Both the Northern Territory and Tasmania only have two services for their whole state. Access to programs in metropolitan areas in some areas is also low despite services being available (Figure 2). Socio-economic factors included in the Spatial Accessibility Model for Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation [13] showed that:

a) 73% (n=228) of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs in Australia needed a referral prior to patients accessing their program.

b) 68% (n=228) of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs in Australia accept all age groups into their programs. Of the 32% that did not accept all age groups into their programs almost all accepted patients from 35 to 85 years and older into their programs.

c) Less than half of the Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs in Australia accept patients with the following coronary heart disease conditions: Dressler’s Syndrome, Atrial Thrombosis Auricle Append Ventricular with Acute Myocardial Infarction, Ruptured Papillary Muscle Complications Following Acute Myocardial Infarction, Ruptured Chordae Tendineae Complications Following Acute Myocardial Infarction, Ruptured Cardiac Wall without Hemopericrd Following Acute Myocardial Infarction, and Haemopericardium Current Complications Following Acute Myocardial Infarction. The survey results also reveal that heart failure patients are not accepted at all Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs.

d) All Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs in Australia were each run with very limited and specific hours of operation, with some programs operating as little as 2 hours a week.

e) Only 2% (n=4.56) of the Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs ran out of hours sessions for patients.

f) More than half (56%, n=228) of the Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs conducted both group and individual sessions. Group only sessions were conducted by 36.8% of the total number of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs in Australia. Individual only sessions were run by only 6.6% of the Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs.

g) A large percentage of the Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs had each of these components recommended as best practice within their program. However, the survey also found that only 49% (n=228) of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs had all 6 recommended components. Therefore, most Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs within Australia failed to meet the National Heart Foundations’ recommendation of what a Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Program should comprise.

h) A majority of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs operate out of an acute public hospital (51% n=228). Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs offering alternative modes of delivery such as: telephone service (27%), home visits (25%), postal (12%) and internet (2%), are limited.

i) Only 2% (n=228) of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs ran an after-hours service.

j) 54% of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs only offer their service through one delivery setting. Only 3% of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs were found through the survey to offer their service through 5 settings.

k) Only 23% (n=52.44) of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs in Australia are provided to the patient as a free service. Schemes to make the Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs accessible to poorer patients such as Medicare (59%), Centrelink (56%), Health Card (57%) and Department of Veteran Affairs Cards (70%) were not accepted at all programs. Extra costs were also identified through the survey which ranged from a gold coin donation per session to $60 per session.

l) Completion rates of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs are low. Only 14% (n=228) of Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs had 100% of patients complete their program with 18% of Phase 2 Cardiac Programs having half or less of their patients complete the program.

Discussion

This research has shown that while studies like [15] highlight the inequitable distribution of cardiovascular services in Australia, barriers to accessing cardiac rehabilitation services are not just related to physical distance, and the availability of reliable transport. Results from this study support the idea developed by Cromely & McLafferty [12] who state that, people trade off geographical and nongeographical factors in making decisions about health service use. Accessibility to Cardiac Rehabilitation services is more than the existence of a service within a geographic location and the availability of reliable transport. Geographic and socio-economic variables impact upon the accessibility of rural and remote population centres to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs across Australia. In a climate where the increasing burden of cardiac disease continues to put strain on the governments limited funds for health care services and policy makers demand empirical evidence to support decision making, this type of spatial modelling provides an opportunity to better understand where future investment in existing services is needed [16-19].

Conclusion

The spatial model of accessibility to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation [13] has been used to identify areas where accessibility to these programs could be improved and where new programs or models of delivery should be established to enhance accessibility in areas that are currently poorly served. This research has identified that there is a need for better service planning aimed at increasing the accessibility to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs within Australia. The factors affecting the accessibility of at-risk populations should be considered and the current services should be improved to meet the specific needs of the population that they could service.

References

- Eckert KA, Taylor AW, Wilkinson D (2004) Does Health Service Utilisation Vary by Remoteness? South Australian Population Data and the Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 28(5): 426-432.

- Savage S, Bailey S, Wellman D, Brady S (2005) Service Provision Factors that Affect the Health and Wellbeing of People Living in Lower SES Environment: The Perspective of Service Providers. Australian Journal of Primary Health 11(3).

- Tonkin AM, Bauman AE, Bennett S, Dobson AJ, Hankey GJ, et al. (1999) Cardiovascular Health in Australia: Current State and Future Directions. Asia Pacific Heart Journal 8(3): 183-187.

- Rowland D, Lyons B (1989) Tripple Jeopardy: Rural, Poor and Uninsured. Health Services Research 23(6): 975-1004.

- Davis K (1991) Inequality and Access to Health Care. The Milbank Quarterly 69(2): 253-273.

- Humphreys JS (2000) Rural Families and Rural Health. Journal of Family Studies 6(2): 167-181.

- Parker EB, Campbell JL (1998) Measuring Access to Primary Medical Care: Some Examples of the Use of Geographical Information Systems. Health and Place 4(2): 183-193.

- Clark RA, Coffee N, Eckert K, Turner D, Tonkin A (2011) Cardiac ARIA: A Geographic Approach to Measure Accessibility to Cardiac Services in Australia Before and After an Acute Cardiac Event. Australian Journal of Critical Care 24(1): 60.

- Clark RA, Coffee N, Eckert K, Turner D, Coombe D, et al. (2010) Where Not to Have a Heart Attack in Australia: The Cardiac ARIA Index. Heart Lung Circulation 19 (Suppl 2): S159.

- Thornbill M, and Stevens JA (1998) Client Perceptions of a Rural-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation Program: A Grounded Theory Approach. Australian Journal of Rural Health 6(2): 105-111.

- Veitch PC, Sheehan MC, Holmes JH, Doolan T, Wallace A (1996) Barriers to the Use of Urban Medical Services by Rural and Remote Area Households. Aust. J. Rural Health 4: 104-110.

- Cromley EK, and McLafferty SL (2002) In: A division of Guilford Publications, GIS and Public Health, The Guilford Press, New York.

- van Gaans D, Hugo G, Tonkin A. (2016) The Development of a Spatial Model of Accessibility to Phase 2 Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs. Journal of Spatial Science 61(1).

- Penchansky R, Thomas JW (1981) The Concept of Access: Definition and Relationship to Consumer Satisfaction. Medical Care 19(2): 127-140.

- Clark RA, Driscoll A, Nottage J, McLennan S, Coombe, DM (2007) Inequitable Provision of Optimal Services for Patients with Chronic Heart Failure: A National Geo-Mapping Study. Medical Journal of Australia 186(4): 169-173.

- Brual J, Gravely-Witte S, Suskin N, Stewart DE, Macpherson A, et al. (2010) Drive time to cardiac rehabilitation: at what point does it affect utilization? Int J Health Geogr 9: 27.

- Johnson J E, Weinert C, and Richardson JK (2001) Rural Residents Use of Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs. Public Health Nursing 15(4): 288-296.

- Higgins RO, Murphy BM, Goble AJ, Le Grande MR, Elliot PC, et al. (2008) Cardiac Rehabilitation Program Attendance After Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery: Overcoming the Barriers. Medical Journal of Australia 188(12): 712-714.

- Schulz DL, McBurney H (2000) Factors which Influence Attendance at a Rural Australian Cardiac Rehabilitation Program. Coronary Health Care 4(3): 135-141.