Knowledge, Attitude and use of Antibiotics in Upper Respiratory Tract Infections among General Population Attending the Primary Health Care Centers in Bahrain

Basheer Makarem*, Fatema Alrowaiei*, Sameera Abdullah*, Anwar Alsayed, Fatima Aldoseri, Marwa Darrai, Marwa Sameer, Noora Ahmadi, Noora Bahzad, Omaima Hamada, Shaikha Albuarki and Fatima Alaqra

Department of Family and Community Medicine, Arabian Gulf university, Bahrain

Submission: January 31, 2019; Published: March 14, 2019

*Corresponding author: Basheer Makarem, Fatema Alrowaiei, Sameera Abdullah, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Arabian Gulf university, college of medicine and medical science, Manama, Bahrain

How to cite this article:Basheer M, Fatema A, Sameera A, Anwar A, Fatima A, et al. Knowledge, Attitude and use of Antibiotics in Upper Respiratory Tract Infections among General Population Attending the Primary Health Care Centers in Bahrain. JOJ Pub Health. 2019; 4(3): 555638. DOI: 10.19080/JOJPH.2018.04.555638

Abstract

Misconceptions about antibiotic usage in relation to URTIs among people have potentially led to inappropriate use of antibiotics worldwide. The aim of this study was to provide data regarding public awareness about antibiotics usage for URTIs among Bahrainis and thus to help the health educators to develop strategies to limit the antibiotics misuse such as public awareness campaigns. The main objective of this study was to assess the knowledge, attitude and practice towards antibiotics in relation to URTIs among Bahraini population. The study represents a cross sectional survey using an interviewer administered questionnaire. Data was collected from a sample of 384 Bahrainis attending the randomly chosen health centers of Bahrain.

Majority of Bahrainis (56.3 %) believed that antibiotics are used to treat cold and flu. 58.3 % thought that antibiotics are used to treat viral infections. 39.3% believed that antibiotics are used to treat fever. 57.5% agreed that taking antibiotics during cold and flu helps them to recover faster, while 51.8% agreed that taking antibiotics can prevent the complications of cold and flu. 32.6% used antibiotics whenever they had the symptoms of cold/flu. 26% kept the left-over antibiotics to use them in future for similar cold and flu symptoms. 64.8% took antibiotics to feel better if necessary and 51% stopped taking antibiotics once they felt better without completing the course. Our findings indicated that misconceptions regarding usage of antibiotic in relation to URTIs exist among Bahrainis included in this study. Therefore, improving appropriate knowledge regarding antibiotic usage is required.

Keywords:Upper respiratory tract infections; Prescribing antibiotics in primary health care centers; Knowledge & attitude towards antibiotics use; Misuse of antibiotics; Level of knowledge in relation to antibiotic use.

Abbreviations: URTIS: Upper Respiratory Tract Infections; BBK: Bank of Bahrain And Kuwait; HC: Health Center; SPSS: Statistical Package for The Social Sciences.

Introduction

Because of their widespread availability and familiarity, generally low cost, and relative safety, antibiotics are among the most misused of all medicines [1]. Unfortunately, the use and misuse of antibiotics has driven the relentless expansion of resistant microbes leading to a loss of efficacy of these “miracle drugs” [1]. Bacterial resistance to antibiotics is an increasing, worldwide problem [2]. One of the most important attributing factors to this serious problem is the increased incidence of inappropriate use of antibiotics [3]

It was found in several studies that a large number of antibiotics are prescribed without a clear indication [2,4]. The rate of inappropriate antibiotic use reached up to 43% in some studies [5]. An understanding of the determinants of antibiotic consumption is critical to explain current patterns of use and to devise programs to reduce inappropriate use. Patient motivations included the desire for a tangible product of the clinical encounter coupled with incorrect perceptions of the effectiveness of antibiotics, particularly in viral infections. Physician behavior could be explained by such factors as lack of information, a desire to satisfy patient demand, and pressure from managed care organizations to speed throughout [6] In order to reduce the rate of antibiotic misuse, a well-organized and effective antibiotics program has to be implemented in all health care facilities.

This research would assess antibiotics awareness for URTIs in particular over other infections; because Antimicrobials were extensively used in primary care, mainly for treating URTIs [7]. In addition, URTIs constituted a major cause of school absenteeism and posed an additional burden on health care delivery in Bahrain. However; the etiology was usually viral and, hence, did not necessitate antibiotic prescription [8]; evaluating patient’s misconceptions about the effectiveness of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) and raising their awareness about the problem of antibiotics misuse, may help in reducing the inappropriate use of antibiotics.

Literature Review

Knowledge varied in countries about antibiotic responses. In Malaysia, nearly 55% of the respondents who were from general public had a moderate level of knowledge. Among Malaysian population 76.7% correctly identified that antibiotics were indicated for the treatment of bacterial infections. However, 67.2% incorrectly thought that antibiotics were also used to treat viral infections. Moreover, 59.1% of the respondents were aware of antibiotic resistance phenomena in relation to overuse of antibiotics. Poor level of knowledge was found in less than one-third of the respondents whereas more than one-third of the respondents wrongly self-medicate themselves with antibiotics once they have a cold [9]. Another study which was done in Hong Kong found that respondents who were also from general population believed that antibiotic was needed for symptoms of URTIs if they felt sick enough to seek medical care [10]. In USA more than half of respondents to a study were not aware of health dangers associated with taking antibiotics, 9% recognized that antibiotics kill “ good microbes “ 5% agreed that “ it is generally unhealthy to take antibiotics “[11].A campaign called “wise use of antibiotics” was held in New Zealand in the 1998 - 2003, to spread awareness about antibiotic use, it was found that only 30% of the respondents from the general population were aware of it, and there was no change noted between the years it was held between, 1998 and 2003. However, misuse had decreased [12]. In the United Kingdom, it was found that generally individuals in UK community did not frequently know that antibiotics were used for bacterial infections but not viral ones, [13] and that those with increased knowledge about antibiotics were more likely to complete a course they were also more likely to selfmedicate and to kept left-over antibiotics [14].

Some people take antibiotics to prevent complications [10] to become better faster [9] and they only use them when they are ill enough [9,10]. However, a large majority in the community of Switzerland believed that doses should be taken at exact intervals as prescribed, including during the night [15]. In New Zealand, there was a significant reduction in those attending doctor for the common cold (24% to 15%). However, it was more likely for patients who received antibiotics previously to return for subsequent consultations for sore throat, suggesting that giving antibiotics encourages patients to return with subsequent illness [16].

A national program to reduce inappropriate use of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections was held in Australia, showed modest but constant positive changes in consumer awareness, believes, Attitude and behavior to the appropriate use of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections. It also showed a decline in total antibiotic prescriptions dispensed in the community [16]. In Jordan, patients visited a community pharmacy to purchase a pharmaceutical product much like they would at a supermarket. Research has shown that the prevalence of self-medication with antibiotics in Jordan was alarmingly high. In this same study, one third of the respondents had reported requesting antibiotic prescription from physicians, more than half had been prescribed antibiotics to treat common cold symptoms and one in every four have been prescribed an antibiotic over the phone without examination [17]. Some interviews in community of Switzerland believed that most respiratory infections, except the common cold, required antibiotic therapy and 11% of them had to exaggerate their symptoms to get an antibiotic prescription from their physician. About 1 patient in 4 saved part of the antibiotic course for future use. Moreover, noncompliance behavior was commonly recorded, only 3 of 4 patients admitted that they took all daily doses. Feeling better, forgetting doses, side effects and bad taste in mouth were some of the reasons which people stopped the course for [15]. A research done in Bahrain revealed that approximately one quarter of prescriptions in primary health care settings in the country included antimicrobials, with the majority of those being used for children with respiratory tract infections. The findings showed that 52% of patients received antibiotics and thus indicated that there was a significant overuse of antimicrobials in the management of URTIs [8]. In a recently published article, antimicrobials were described as the fourth most commonly prescribed drugs in primary healthcare facilities in Bahrain. This tendency of over prescription of antibiotics was related to the lack of national guidelines as a driving force for prescription of antibiotics. [18]. In Saudi Arabia, a research was done in King Saud University about Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices towards Medication Use among Health Care Students and concluded that Pharmacy students had better knowledge about medication practice compared to other health sciences students. All other health sciences students lacked the appropriate attitude and practice related to the safe use of medications [19].

Aim

The aim of this study was to provide baseline data regarding public awareness of antibiotics usage for URTIs in Bahrain in order to help the health educators to develop preventive strategies such as public awareness campaigns.

Objectives

a) To assess the level of knowledge towards antibiotics use in URTI among adult Bahrainis.

b) To describe the attitude and pattern of use of antibiotics in URTIs in this population.

c) To study the factors related to their knowledge, attitude and use of antibiotics.

Material and Methods

Study design

Cross-sectional

Study population

Adult Patients who attended the primary health care centers and were diagnosed with URTIs were included in the study.

Sample size

The sample size was 384, calculated according to the following formula:

n = Z 1-α/22. p (1-p)

E2

Where:

n = sample size

Z = z value from table of normal (z) distribution (1.96 for 95% confidence level)

p = prevalence estimating as 50% because no similar studies were previously conducted.

E = error

Sample technique

Bahrain is divided into 5 governorates; two health centers were chosen randomly from each governorate. The following are the health centers which were chosen:

a) National Bank of Bahrain-Arad

b) BBK Hidd Health Center

c) Al-Naim Health Center

d) Al-Hoora Health Center

e) Budaiya Health Center

f) Isa Town Health Center

g) Ahmed Ali Kanoo Health center

h) Hamad Kanoo Health center

i) Hamad Town Health Center

j) Mohammed Jassim Kanoo Health center

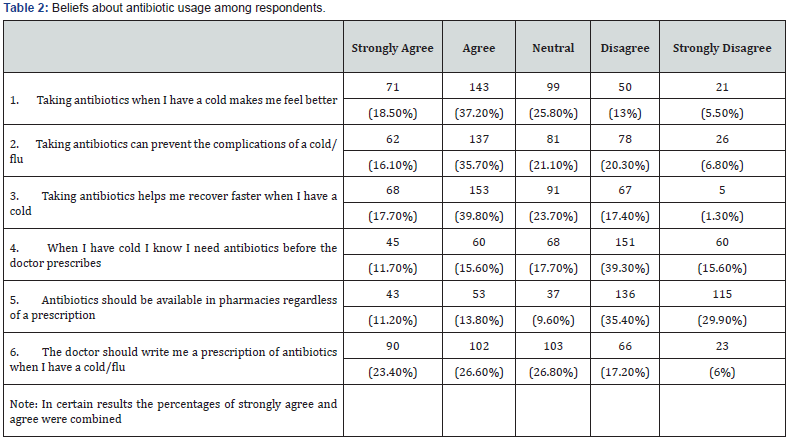

Sample size distribution

a) The number of visits per year to each health center was identified from the Ministry of Health website “http:// www.moh.gov.bh/PDF/Publications/statistics/HS2012/ hs2012_a.htm” in 2013.

b) The total number of visits in the chosen health centers was (i.e. 1701249). (Table 1).

c) Percentage in each HC was multiplied by the sample size (i.e. 384) to calculate the number of patients to be chosen.

d) Participants were chosen in a convenient way.

e) Near the pharmacy within each health center, those patients who came to collect their medicines were asked by a member of the research group that if they were diagnosed with URTIs and based on that the questionnaire was given while they were waiting for their medications and were collected back at the same time once they finished answering the questionnaire.

Study instrument

A questionnaire was designed by the researchers (Appendix 1) and a pilot study was conducted. The questionnaire was first written in English and then translated to Arabic. Questionnaires were distributed in both languages English and Arabic. It was then divided into four sections, which included:

a) Information about socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents such as age, gender, education level, profession and marital status.

b) Knowledge; aimed to assess the extent of the individual’s knowledge about antibiotics in general and its use in URTIs.

c) Attitude; aimed to determine the individual’s attitude towards the use of antibiotics.

d) Practice; elucidated how, when & why the individual used antibiotics.

The patients answered the questionnaire on the spot after a complete explanation by the members of the research group. A pilot study was conducted on 20 patients who were not included in the research at Sabah Al-Salem Health Center and Baraiya coastal Clinic, and it was estimated that it required approximately 5 Minutes on average for the questionnaire to be answered. The pilot study aimed to assess the duration, simplicity and the understanding of the questions. It was understood well by the participants and all questions were answered without participants facing any problems.

Ethical consideration

The research committee in the university and in The Ministry of Health reviewed the protocol. The questionnaire was self-answered, and a verbal consent was taken after a complete explanation of the study by the members of the group to the participants. It was also explained to them that there would no indication of their identity, and the information would be processed in confidentiality. Patients were assured that the participation was voluntary and refusal to participate would involve no penalty.

Statistical analysis

SPSS program was used to analyze the data collected & demonstrate the results of the research. The level of knowledge was rated as high, medium or low. The individual was considered of high knowledge when 6 or 7 of the knowledge questions were answered correctly, medium knowledge when 3-5 questions were answered correctly & low knowledge when 1- 2 questions were answered correctly. Percentages were used to estimate the level of knowledge. Attitude towards the antibiotic usage was analyzed according to Likert scale and the practice was assessed by ‘yes or no’ questions & each question was analyzed separately. Percentages were also used.

Inclusion criteria:

The research included the individuals who were 18 years old and above, could write & read Arabic and English, were aware of the term “antibiotics” and were diagnosed with URTIs.

Exclusion Criteria:

The individuals who had a medical condition that prevented them from writing or reading were excluded.

Results

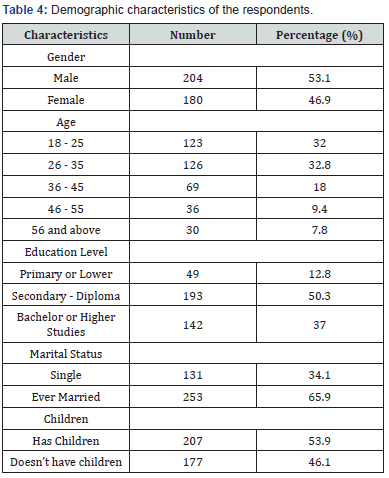

Knowledge

The total respondents were 384. Out of which 204 (53.12%) were males and 180 (46.9%) were females. Most of the respondents were between the age groups 18-25 (123 respondents) and 26-35 (126 respondents). More than half of respondents (253) were from the category of “ever married” (Table 2).

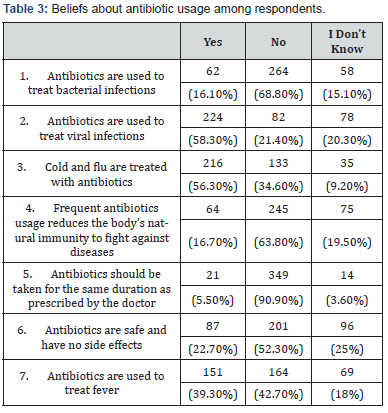

Out of the total 384 respondents only 62 (16.1%) answered correctly that antibiotics are used to treat bacterial infections while 224 (58.3%) respondents answered that antibiotics are used to treat viral infections. Among these 139 (36.2%) respondents answered that antibiotics are used to treat bacterial as well as viral infections (Table 1).

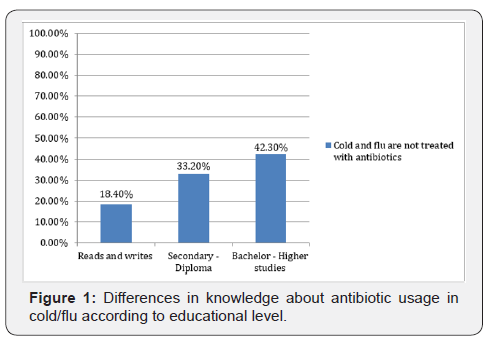

Majority of respondents i.e. 216 (56.3%) responded that cold and flu are treated with antibiotics while 133 (34.6%) respondents denied that antibiotics are used to treat cold and flu. 42.30% of participants with a degree of bachelors or higher studies responded with the correct answer and said that antibiotics are not used for the treatment of cold and flu, while those with an educational level of secondary /diploma and or could just read and write were 33.20% and 18.40% respectively (Figure 1).

Out of 384 respondents, 245 (63.8%) believe that frequent antibiotic usage didn’t reduce their natural immunity to fight against infectious diseases while 64 (16.7%) answered that frequent antibiotic usage did reduce the natural immunity. Out of the total participants only few i.e. 21 (5.5%) answered that antibiotics should be taken for the same duration as prescribed by the doctor. On the other hand, fewer than half responded that antibiotics are safe and have no side effects (22.7 %) and are used for treating fever (39.3%) (Table 1).

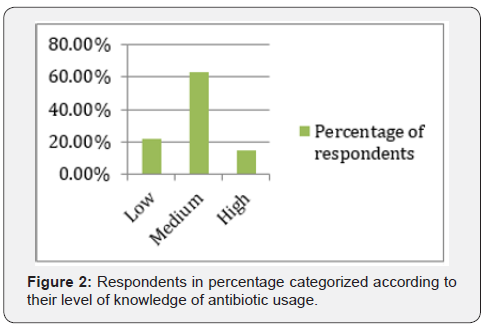

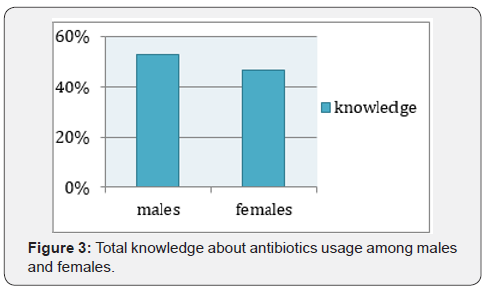

Among the total participants, 14.8 % were those who scored between 6 and 7 (i.e. gave 6 or 7 correct answers in the knowledge items) and thus were regarded to have high knowledge. 63% and 22.2 % were those with moderate (scored 3-5) and low (scored 1-2) knowledge respectively (Figure 2). The total knowledge about antibiotics usage was more in males (52.70%) in whom the total number of correct answers were more than females (46.90%) (Figure 3).

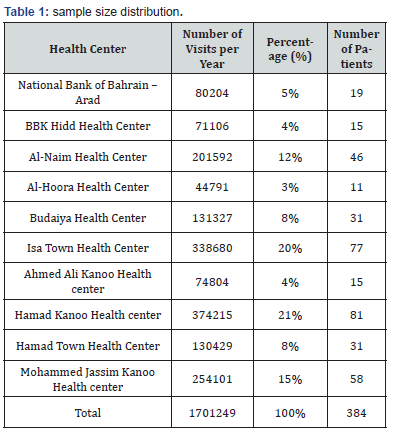

Beliefs

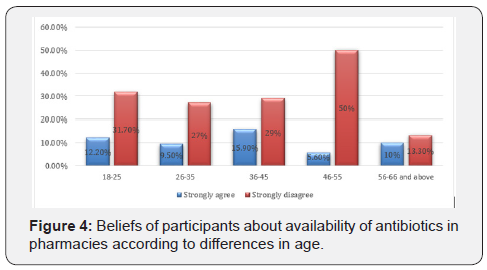

More than half of respondents 55.7% (214) agreed that taking antibiotics when they had a cold made them feel better (71 strongly agreed, 143 agreed) while on the other hand only 13 % disagreed and 5.5% strongly disagreed (Table 3).Most respondents also believed that taking antibiotics can help them to recover faster (57.5%) when they had a cold and that taking antibiotics can prevent the complications of cold and flu (51.8%).Approximately half of the respondents (50%) believed that the doctor should prescribe them antibiotics when they had a cold. However, majority of the respondents 251 (65.3%) didn’t want antibiotics to be available in pharmacies among which 35.4 % disagreed while 29.9% strongly disagreed.15.9% participants between the age group 36- 45 strongly agreed that antibiotics should be available in pharmacies regardless of prescription while almost half of the patients (50%) in the age group 46- 55 and 30.1% of participants in the age group between 18-25, strongly disagree with the availability of antibiotics in pharmacy (Figure 4).

Practice

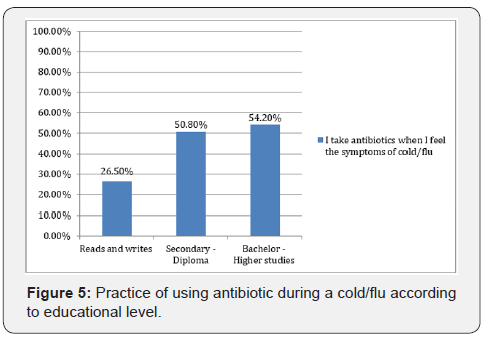

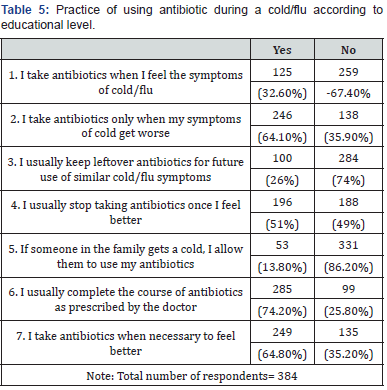

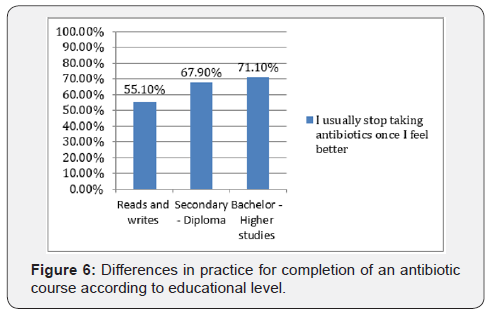

Out of 384 respondents, 125 (32.6%) take antibiotics when they have symptoms of cold and flu. 64.1 % of respondents take antibiotics when their symptoms of cold and flu get worse (Table 4). 54.20% of participants with a degree of bachelors /higher studies did not take antibiotics when they had the symptoms of cold and flu, while 50.80% and 26.50% were among those with an educational level of secondary /diploma and or could just read and write were respectively (Figure 5).Almost half of the respondents (51%) stop taking antibiotics once they feel better. On the other hand, 64.8% take antibiotics when necessary to feel better. 26% among them kept the leftover antibiotics to use them in the future for similar symptoms of cold and flu, however, only few (13.8%) said that they give their antibiotics to one of the family members if they get a cold (Table 5). 71.10% of participants with a degree of bachelors or higher studies didn’t stop taking antibiotics once they felt better, while those with an educational level of secondary /diploma were 67.90% and those who could just read or write were 55.10% (Figure 6). Significant tests were done for knowledge, beliefs and practice items but there were no significant differences.

Discussion

The findings have shown that the study population had less knowledge regarding the indication for the treatment of the viral infections. The proportion of the respondents who thought that antibiotics are effective for viral infections (58.3%) was comparable with a survey conducted in Malaysia (67.2%). Many of the respondents thought that antibiotics are used for viral and bacterial infections (36.2%) and can’t differentiate between them. Most of the respondents (90.9%) had correct knowledge of completing the full course of antibiotics even when symptoms of infection are improving, which is higher compared with other survey done in Malaysia (71.7%). However, those who knew the need for completing the full course did not necessarily practice it (51%) and stop when they feel better. Therefore, our results suggest that better knowledge does not necessary imply appropriate attitude in relation to antibiotics use. Regarding the usage of antibiotics, the percentage of the respondents who keep antibiotics left-over for future use (26%) was compared with a study done in Jordan (31%), however, only few (13.8%) said that they give their antibiotics to one of the family members if they get a cold. Overall, (14.8%) of the respondents had higher level of knowledge, which is less compared with Indonesia (34%). However (63%) had moderate knowledge, which is more compared with the same study in Indonesia (35%). Poor level of knowledge was found in both (22.2%) and (31%), this study and Indonesia, respectively.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Nearly more than half of the respondents had a moderate level of knowledge scoring (3-5) right answers. Only 16.1% were able to identify that antibiotics were used against bacterial infections. On the other hand, 36.2% incorrectly though that antibiotics are used for both bacterial as well as viral infections. Majority of the respondents believed that taking antibiotics will help them recover faster but at the same time they believed that antibiotics should not be freely available in pharmacies. 64.1% of respondents started using antibiotics only when their symptoms got worse, whereas educated participants completed the full course of antibiotics. These results identified that specific groups should be targeted for educational inventions. Certain measures are still needed to increase the level of knowledge usage in cold and flu situations. However, it is suggested that a well-organized program should be undertaken to improve the knowledge, beliefs, practice and appropriate use of antibiotics.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank questionnaire participants who kindly devoted their time to participate. We would like to thank the Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine and Medical Sciences at Arabian Gulf University to assist us in conducting the research.

References

- http://www.who.int/drugresistance/use/en/.

- Mera RM, Miller LA, Daniels JJ, Weil JG, White AR (2005) Increasing Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant Streptococcus Pneumoniae in the United States over a 10-Year Period: Alexander Project. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 51(3): 195-200.

- Jameela Al Salman, Aysha Husain, Muneer M (2012) Trends of Empiric Antibiotic Usage in an Accident and Emergency Department in a Secondary Care Hospital. Bahrain Medical Bulletin 34(4): 169-180.

- (2001) WHO Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance WHO. Hospitals: Recommendations for Intervention. Geneva, Switzerland, WHO, pp. 26-35.

- Hecker MT, Aron DC, Patel NP, Lehmann MK, Donskey CJ (2003) Unnecessary Use of Antimicrobials in Hospitalized Patients: Current Patterns of Misuse with an Emphasis on the Antianaerobic Spectrum of Activity. Arch Intern Med 163(8): 972-978.

- Avorn J, Solomon DH (2000) Cultural and Economic Factors that (Mis) Shape Antibiotic Use: The Nonpharmacologic Basis of Therapeutics. Ann Intern Med 133(2): 128-135.

- Al Khaja KA, Sequeira RP, Damanhori AH, Ismaeel AY, Handu SS (2008) Antimicrobial Prescribing Trends in Primary Care: Implications for Health Policy in Bahrain. Journal Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 17(4): 389-396.

- Senok AC, Ismaeel AY, Al-Qashar FA, Agab WA (2009) Pattern of Upper Respiratory Tract Infections and Physicians’ Antibiotic Prescribing Practices in Bahrain. Med Princ Pract 18(3): 170-174.

- Ling Oh A, Hassali MA, Al-Haddad MS, Syed Sulaiman SA, Shafie AA (2011) Public knowledge and attitudes towards antibiotic usage: a cross-sectional study among the general public in the state of Penang, Malaysia. J Infect Dev Ctries 5(5): 338-347.

- You JH, Yau B, Choi KC, Chau CT, Huang QR (2008) Public knowledge, attitudes and behavior on antibiotic use: a telephone survey in Hong Kong. Infection 36(2): 153-157.

- Vanden Eng J, Marcus R, Hadler JL, Imhoff B, Vugia DJ, et al. (2003) Consumer Attitudes and Use of Antibiotics. Emerg Infect Dis 9(9): 1128-1135.

- Widayati A, Suryawati S, de Crespigny C, Hiller JE (2012) Knowledge and beliefs about antibiotics among people in Yogyakarta City Indonesia: a cross sectional population-based survey. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 1(1): 38.

- Curry M, Sung L, Arroll B, Goodyear Smith F, Kerse N (2006) Public views and use of antibiotics for the common cold before and after an education campaign in New Zealand. N Z Med J 119(1233): U1957.

- McNulty CA, Boyle P, Nichols T, Clappison P, Davey P (2007) The public's attitudes to and compliance with antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother Suppl 1: i63-i68.

- Wilson AA, Crane LA, Barrett PH, Gonzales R (1999) Public Beliefs and Use of Antibiotics for Acute Respiratory Illness. J Gen Intern Med 14(11): 658-662.

- Pechère JC (2001) Patients' interviews and misuse of antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis 33 Suppl 3: S170-S173.

- Shehadeh M, Suaifan G, Darwish RM, Wazaify M, Zaru L, Alja'fari S (2012) Knowledge, attitudes and behavior regarding antibiotics use and misuse among adults in the community of Jordan. A pilot study. Saudi Pharm J 20(2): 125-133.

- Al Khaja KA, Sequeira RP, Damanhori AH, Ismaeel AY, Handu SS (2008) Antimicrobial prescribing trends in primary care: implications for health policy in Bahrain. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 17(4): 389-396.

- Abdullah TE (2013) Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices towards Medication Use among Health Care Students in King Saud University 1(2): 66-69.