American Indian Tribal College Student’s Knowledge, Attitudes and Beliefs about Recreational and Traditional Tobacco Use

Kathryn Rollins1,2,3*, Christina M Pacheco JD1,2,3, Sean M Daley3,4,5, Niaman Nazir1,2, Charley Lewis1,2,3 , Won S Choi1,6 and Christine M Daley1,2,3,6

1Center for American Indian Community Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, USA

2Department of Family Medicine, University of Kansas Medical Center, USA

3American Indian Health Research and Education Alliance, Inc Shawnee, USA

4Center for American Indian Studies, Johnson County Community College, USA

5Department of Anthropology, Johnson County Community College, USA

6Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, USA

Submission: May 03, 2017; Published: May 26, 2017

*Corresponding author: Kathryn Rollins, Center for American Indian Community Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard, Mail Stop 1030, KS 66160, Kansas City, USA,Email: krollins@kmu.edu

How to cite this article: Kathryn R, Christina M P J, Sean M D, Niaman N, Charley L, et al. American Indian Tribal College Student’s Knowledge, Attitudes and Beliefs about Recreational and Traditional Tobacco Use. JOJ Pub Health. 2017; 2(1): 555580. DOI:10.19080/JOJPH.2017.02.555580

Abstract

Introduction: American Indians (AI) have the highest smoking rates of any racial/ethnic group in the U.S., in addition to low success rates of tobacco cessation. The substitution of commercial tobacco for traditional tobacco may have played a role in the prevalence rates of recreational tobacco use among AI. The present study explored the impact of tribal college students’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about traditional tobacco use on their recreational cigarette smoking behaviors.

Methods: Multiple methods were used to recruit participants attending a tribal college. A total of 101 AI tribal college students completed a demographic survey and participated in focus groups or individual interviews assessing traditional and recreational tobacco use.

Results: AI tribal college student’s recreational smoking has an influence on various health behaviors, including poor eating habits, decreased physical activity, and elevated tobacco use in association with alcohol consumption. Differences between the use of and motivation behind smokeless tobacco and cigarette use were seen. In addition, participants reported differences between using tobacco for traditional purposes such as in ceremony or during prayer in comparison to recreational tobacco use. Conclusion: These findings highlight AI students’ beliefs about recreational tobacco, smokeless tobacco, and traditional tobacco use. Differences related to behaviors associated with traditional tobacco use have important implications for future cessation efforts for AI smokers.

Keywords: Smoking; American Indians; Tribal College; Tobacco

Abreviations: AI: American Indians; CBPR: Community-Based Participatory Research

Introduction

American Indians (AI) have a multifaceted relationship with tobacco. For many AI, tobacco is a sacred plant used for ceremonial and spiritual purposes. It is well-documented that some tribes, particularly tribes located along the Eastern seaboard, Great Plains and Great Lakes areas, used tobacco for medical purposes to heal the mind, body and spirit [1-4]. Tobacco smoke cleanses, purifies and blesses and is often used as a gift [3-5]. Some AI believe that tobacco was given to their people as a means of establishing a direct communication link with the Creator and the spiritual world [4,6] and therefore should be used in a respectful manner. Uses and frequency of use of traditional tobacco varies among tribes [1,2,4-6] some AI use traditional tobacco daily, others use it a few times per year [6].

Today, it is not uncommon to see commercial tobacco substituted for traditional use [1-4] and, in many cases, imparted with its meaning [5]. Federal policies and practices aimed at exterminating or assimilating AI prohibited individuals from performing traditional ceremonies and rituals [3,6,7]. During this time, the cultivation and use of traditional tobacco was both difficult and dangerous [3,6]. Commercial tobacco was a practical alternative and allowed many AI to continue traditional and spiritual practices undetected [3,6]. Some believe that the repression of traditional and spiritual practices and resulting substitution of commercial tobacco for traditional tobacco may have played a part in the high prevalence rates of recreational tobacco abuse among AI [2,3,6].

While some strides have been made toward decreasing smoking among AI youth, even in adulthood, AI still have high rates of recreational smoking (31.5%) [8]. Leading to a disproportionate level of tobacco related illnesses. Despite disproportionate prevalence rates among AI, little is known about the impact of tribal college students’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about traditional tobacco use on their recreational cigarette smoking behaviors. As a portion of a larger longitudinal study [9,10]. We sought responses from AI tribal college students to understand better ways to target cessation efforts.

Methods

Study Participants

Eight individual interviews and 12 focus groups were conducted with tribal college students (N=101) in the Midwest. Eligible participants included men and women who were enrolled in federally recognized tribes, were at least 18 years of age, and able to give written consent. Recruitment, led by AI research assistants, was done via word-of-mouth, emails sent through the college email system, posters/flyers, and social media blasts on facebook™. Participants received a $25 gift card and a meal for their time and participation. All study protocols were approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center’s Human Subjects Committee and the tribal college’s institutional review board.

Measures

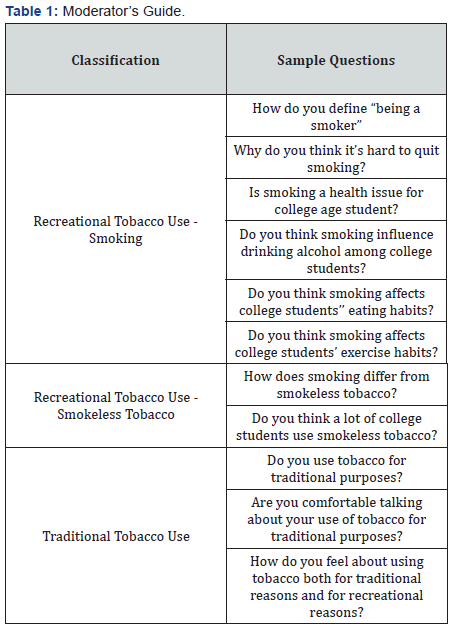

To assess their knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about traditional and recreational tobacco use, college students were asked questions relating to traditional use of tobacco, recreational use of tobacco, and the differences between the two. Each session was conducted by an AI research team member to assure culturally sensitive interaction. A moderator’s guide, consisting of semi-structured open-ended questions (Table 1), was developed by the entire research team in partnership with our community advisory board and based on information gained from our previous research [1,11,12].

Procedures

This study was originally intended to be a focus group study, however due to circumstances out of our control (i.e. finals and class schedules), some students were unable to attend a scheduled focus group time. Eight individual interviews were conducted because we felt these participants offered useful insight to our study and we wanted to ensure their opinions were heard. Sessions were held on campus at multiple times to accommodate students with various schedules. Prior to each focus group or interview, participants were consented privately and asked to complete a brief demographic survey.

Following the moderator’s guide created by the research team, the moderator facilitated the session while the assistant moderator attended to other tasks, such as consenting latecomers and taking notes. Participants were encouraged, but not required, to respond to each question. The moderator expanded upon the responses if needed to encourage group discussion or responses from the individual interviews. The duration of each focus group was between 60 and 75 minutes and each interview last approximately 15 to 30 minutes.

Analysis

Focus groups and interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Following a community-based participatory research (CBPR) method developed by the team [12], codebooks were developed from the transcripts. Both researchers and community members, blinded to each other, coded the initial transcripts. Coders identified preliminary themes which were then combined into thematic statements and agreed upon by the entire research team, including community representatives. Here, we present those themes for which wereached theoretical saturation. All exemplary quotes were identified by community members who were alumni of the tribal college to ensure fair representation.

Results

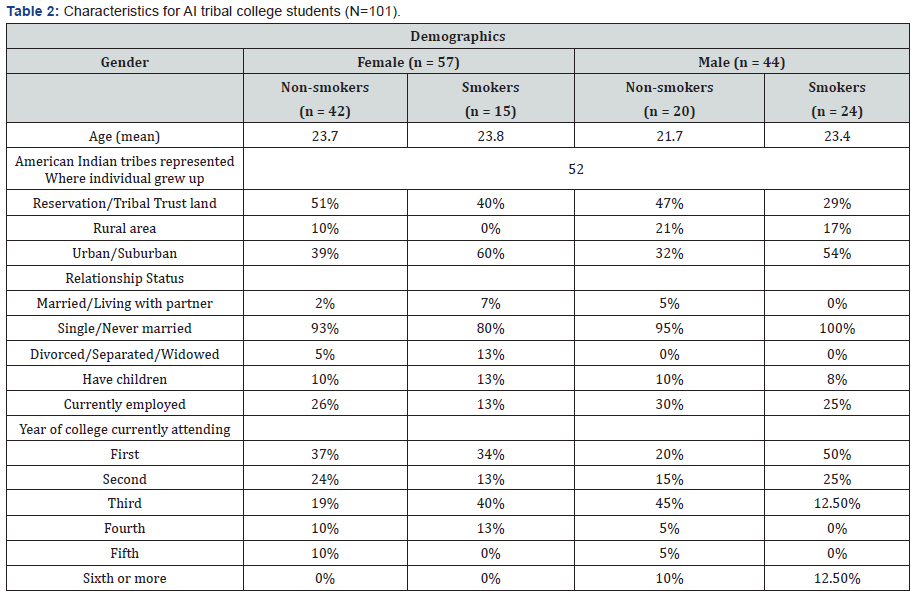

A sample of 101 AI tribal college students who self-identified as smokers or non-smokers participated in this study. All participants were enrolled in a federally recognized AI tribe and were in one of their first three years of college. Full demographic information is available in (Table 2). Three predominant categories in the areas of recreational smoking and health behaviors, smokeless tobacco, and traditional tobacco emerged from the data.

Recreational Smoking & Related Health Behaviors

Many students believed that recreational smoking affects various health behaviors. Participants often discussed a connection between smoking and poor health choices, including the impact of smoking on eating habits, physical activity, and alcohol consumption. Participants discussed students who smoke in an effort to aid in weight loss or prevent weight gain. A female non-smokers stated, “I’ve had friends in high school that smoke so that they don’t eat.” Another female non-smoker recounted her personal experience with smoking and weight loss, “Last semester I picked it (smoking) back up when I was too lazy to work out. I thought well I know when I smoke I lose about ten pounds, so I just picked it right back up. And it worked, but it’s horrible.”

These groups, particularly smokers, also agreed that smoking decreases physical activity. One individual focused on the way smoking affects a student’s physical activity, “If you smoke you get problems like trouble breathing. And you don’t want to work out if you have that kind of problem. A lot of athletes and people who work out every day then they don’t smoke as much or hardly smoke.” Furthermore, students spent time discussing the impact of smoking on health, as one student explained, “I can’t breathe. I know it’s bad for me. You know, I’m taking something out of a box and putting it in my mouth and setting fire to it. And right on the box it says, these things will kill you, basically. But I do it anyway, don’t that seem kind of stupid to you? It seems stupid to me, but I do it anyway. I don’t know.”

Drinking alcohol was seen as a facilitator to smoking. Participants spoke about how alcohol lowers a person’s inhibitions and makes them more likely to smoke. One student stated, “a lot of times when you go out drinking there’s people smoking around you and when you’re in an inebriated state you kind of are like, yeah, I want to try that.” Another student agreed, “I know non-smokers who smoke when they drink, but that’s the only time they smoke.” Additionally, participants discussed how alcohol inhibits quitting smoking, “I had a friend who quitsmoking and didn’t smoke for like a month and got drunk one night and smoked a whole pack. So drinking definitely influences [smoking].” Another student added, “You take a cigarette and you forget, you know, become more susceptible to falling off the wagon.”

Smokeless Tobacco

AI tribal college students saw the use of smokeless tobacco as different from smoking. Participants commonly discussed perceptions associated with smokeless tobacco use and the use of smokeless tobacco as a substitution for smoking. Female smokers and non-smokers alike generally had negative perceptions about smokeless tobacco use and agreed that use is more common among men. A female non-smoker described smokeless tobacco use as a disgusting habit, “They carry it with them and sit it (spit container) down somewhere and it’s like oh my God, that’s so gross.” Discussions among male non-smokers surrounded the difference in nicotine potency and the accessibility of smokeless tobacco. On participant stated, “I used to chew for a long time. It was nice to get that nicotine kick. There’s more nicotine in a dip than two, three cigarettes easily.” Additionally, about half of the male non-smokers had tried or used smokeless tobacco, most citing family and friends as the reason for their initiation. “Got it from buddies, peer pressure and just did it to hang out and chat with them and stuff.”

Male smokers on the other hand focused more on how smokeless tobacco users miss the social aspect of smoking, “It’s not as social and I think that’s the biggest aspect of [it] around here at the college. When you can’t smoke indoors or anything like that, everybody has to go outside and meet… if you’re going to chew or dip or anything like that, you can do it in your room with an empty bottle.” Additionally, male smokers focused on the ease of replacing cigarettes with smokeless tobacco in situations where smoking bans were in place, “I use a company truck so I can’t smoke in the vehicle, so I resort to chew…”

Traditional Tobacco

Participants with experience or knowledge of traditional tobacco use differentiated between traditional and recreational tobacco despite varying use among their tribes. In particular, intentionality as well as the ceremonial and spiritual aspects of traditional tobacco resonated with these students. One student commented, “I think it’s all in the intent of how you’re using it. If you’re using it for spiritual and healing purposes, only then is it acceptable.” Another student added, “Well I know my tribe, we use it to pray with. When we’re going to gather food; it’s like giving thanks or blessing.”

Several students also acknowledged a distinct difference in using tobacco for traditional purposes and its impact on addiction. One student shared, “Recreational smoking… it’s more like an addiction; smoking for recreation (can) cause you (to) want to smoke all the time. Traditional is letting go, in ceremonies…That’s not addicting.” A male smoker spoke Furthermoreabout the spirituality of traditional tobacco, “Talking to God. Its (referencing tobacco) not harmful to your body, it’s actually healthy for you. You can’t use it for recreational purpose, it’s sacred.”

Discussion

Tribal college students face culturally-specific challenges addressing tobacco use and related health disparities. This study specifically explored the possible impact of traditional tobacco use on recreational smoking behaviors. Our focus group participants indicated that individuals may smoke for weight loss. This is consistent with data reported in the literature. For example, studies suggest that college aged women smoke for weight loss and body image reasons [13-18]. However, it is unknown how AI college students may use tobacco for those purposes. More research is needed on this topic. In addition, our focus group participants spoke about physical activity and associated health outcomes in relation to smoking. It has been reported that physical activity decreases when young adults transition into adulthood; in particular, men who entered college experienced the most significant decline of physical activity [19]. Alcohol consumption and drinking frequency are correlated with smoking experimentation and established use [20]. In our sample of AI tribal college students, participants described the experience of quitting as more difficult because of alcohol use. Other U.S. college population studies have reported that parties and group smoking and drinking are associated with higher rates of drinking and smoking [21-24]. Our results are consistent with other findings that support this association [20,24-26] and the notion that smoking may be more acceptable in certain contexts [27].

Even though the general discussion of smokeless tobacco use was negative, descriptions by both males and females about males using smokeless tobacco were largely positive or neutral and referenced to rural and/or reservation living. Images and associations were accepted in certain contexts and perceived as normal behavior. An interesting contrast among smokeless tobacco users and smokers is that smokers claimed smokeless tobacco users miss out on the social aspects of using tobacco. Unlike smokers, it was believed that smokeless tobacco users did not reap the benefits of a shared, social experience, except for those who used smokeless tobacco in areas where smoking was prohibited (such as dormitories or workplaces). These individuals saw the beneficial aspects of smokeless tobacco in that it could be concealed. Thus, people could still get nicotine into their system when otherwise it was not feasible.

Smokeless tobacco use, therefore, presents a certain kind of functionality for those who wish to smoke but cannot due to regulations. This is an important finding because it could mean that we will see rising prevalence of smokeless tobacco use as tribal colleges institute smoke-free and tobacco-free policies on campus, particularly given the high rates of smoking in this population. We are exploring this issue in our larger longitudinal study, as well as in a smokeless tobacco cessation study currently underway. Strong differentiations between traditional and recreational tobacco use were seen among participants. Emphasizing this distinction in tobacco cessation intervention programs may prove to be beneficial. It has been reported that elders associate positive traits with traditional tobacco (spirituality, respect, and humility) versus commercial tobacco (lack of respect for one’s self and others, sickness, and death) [5]. Having a sense of cultural pride and connectedness to these beliefs is a protective factor for recreational smoking [28]. In fact, it has been shown that those who attempt to quit recreational smoking and use tobacco for traditional purposes are more successful compared to those who do not use tobacco traditionally [28]. This needs to be better articulated in educational and prevention programs.

Conclusion

A limited number of studies of AI tribal college students have examined the relationship between traditional and recreational tobacco use. We believe the traditional use of tobacco affects cessation; therefore, capturing this information is critical to designing successful intervention programs. Limitations of this study include the self-reported smoking status and the small sample size. Results cannot be generalized to all AI given the number of tribes currently in the U.S. and the variability of both traditional and recreational tobacco use across the tribes. However, we were able to obtain a diverse sample and reach theoretical saturation. Therefore, we believe these results show us important trends and can be used to develop further studies.

This study is a good first step towards tailoring interventions that respect culture and tradition for tribal college students and has been used to assist in developing a culturally appropriate cessation program for these students, which is currently being tested. It is necessary for intervention efforts to pinpoint social and environmental cues among tribal college students that increase the likelihood of tobacco use. Based on specific health behaviors and traditional practices, educational approaches and interventions used in the U.S. college population may not be applicable to tribal college students. Rather, health promotion initiatives should include the development of new programs or modification of existing ones to better emphasize culture, traditional tobacco use, and specific barriers that tribal college students experience.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the members of the Center for American Indian Community Health and the American Indian Health, Research and Education Alliance for collecting and analyzing this data. These members include Lance Cully (posthumously), Joseph Pacheco, Myrietta Talawyma, Rachael Lackey and Chandler Williams. We would like to thank the staff and faculty at our partner tribal university, without them this work could not have been done. Finally, we would like to express our gratitude for our community advisory board and community collaborators for all of their work and contributions to our shared mission of achieving health equity and equality for American Indian communities in the Heartland.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Daley CM, Greiner KA, Nazir N, Daley SM, Solomon CL, et al. (2010) All Nations Breath of Life: Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities in cigarette smoking among American Indians. Ethn Dis 20(4): 334-338.

- Brokenleg I, E Tornes (2013) Walking Toward the Sacred: Our Great Lakes Tobacco Story. Lac du Flambeau, WI Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Epidemiology Center, USA.

- Nadeau M, Blake N, Poupart J, Rhodes K, Forster JL (2012) Circles of Tobacco Wisdom: learning about traditional and commercial tobacco with Native elders. Am J Prev Med 43(3): S222-228.

- Struthers R, FS Hodge (2004) Sacred tobacco use in Ojibwe communities. J Holist Nurs 22(3): 209-225.

- Margalit R, Watanabe-Galloway S, Kennedy F, Lacy N, Red Shirt K, et al. (2013) Lakota elders’ views on traditional versus commercial/ addictive tobacco use; oral history depicting a fundamental distinction. J Community Health 38(3): 538-545.

- Forster JL, Rhodes KL, Poupart J, Baker LO, Davey C, et al. (2007) Patterns of tobacco use in a sample of American Indians in Minneapolis- St. Paul. Nicotine Tob Res 1(1): S29-37.

- Pacheco CM, Daley SM, Brown T, Filippi M, Greiner KA (2013) Moving forward: breaking the cycle of mistrust between American Indians and researchers. Am J public health 103(12): 2152-2159.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2011) Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports, USA.

- Faseru B, Daley CM, Gajewski B, Pacheco CM, Choi WS (2010) A longitudinal study of tobacco use among American Indian and Alaska Native tribal college students. BMC public health 10(1): 617.

- Choi WS, Nazir N, Pacheco CM, Filippi MK, Pacheco J, et al. (2016) Recruitment and baseline characteristics of American Indian tribal college students participating in a tribal college tobacco and behavioral survey. Nicotine Tob Res 18(6): 1488-1493.

- Makosky Daley C, Cowan P, Nollen NL, Greiner KA, Choi WS (2009) Assessing the scientific accuracy, readability, and cultural appropriateness of a culturally targeted smoking cessation program for American Indians. Health Promot Pract 10(3): 386-393.

- Makosky Daley C, James AS, Ulrey E, Joseph S, Talawyma A et al. (2010) Using focus groups in community-based participatory research: challenges and resolutions. Qual Health Res 20(5): 697-706. li class="ref">Clark MM, Croghan IT, Reading S, Schroeder DR, Stoner SM, et al. (2005) The relationship of body image dissatisfaction to cigarette smoking in college students. Body Image 2(3): 263-270.

- Granner ML, DR Black, DA Abood (2002) Levels of cigarette and alcohol use related to eating-disorder attitudes. Am J Health Behav 26(1): 43- 55.

- Lopez Khoury EN, EB Litvin, TH Brandon (2009) The effect of body image threat on smoking motivation among college women: mediation by negative affect. Psychol Addict Behav 23(2): 279-286.

- Napolitano MA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Fava JL, Marcus BH (2011) Targeting body image schema for smoking cessation among college females: rationale, program description, and pilot study results. Behav Modif 35(4): 323-346.

- Stickney SR, DR Black (2008) Physical self-perception, body dysmorphic disorder, and smoking behavior. Am J Health Behav 32(3): 295-304.

- Ward BW, H Ridolfo (2011) Alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use among Native American college students: an exploratory quantitative analysis. Subst Use Misuse 46(11): 1410-1419.

- Kwan MY, Cairney J, Faulkner GE, Pullenayegum EE (2012) Physical activity and other health-risk behaviors during the transition into early adulthood: a longitudinal cohort study. Am J Prev Med 42(1): 14-20.

- Reed MB, Wang R, Shillington AM, Clapp JD, Lange JE (2007) The relationship between alcohol use and cigarette smoking in a sample of undergraduate college students. Addict Behav 32(3): 449-464.

- Colder, C.R., Lloyd-Richardson EE, Flaherty BP, Hedeker D, Segawa E et al. (2006) The natural history of college smoking: trajectories of daily smoking during the freshman year. Addict Behav 31(12): 2212-2222.

- Stromberg P, M Nichter, M Nichter (2007) Taking play seriously: lowlevelsmoking among college students. Cult Med Psychiatry 31(1): 1-24.

- Piasecki TM, McCarthy DE, Fiore MC, Baker TB (2008) Alcohol consumption, smoking urge, and the reinforcing effects of cigarettes: an ecological study. Psychol Addict Behav 22(2): 230-239.

- Witkiewitz K, Desai SA, Steckler G, Jackson KM, Bowen S, et al. (2012) Concurrent drinking and smoking among college students: An eventlevel analysis. Psychol Addict Behav 26(3): 649-654.

- Cronk NJ, Kari JH, Soloman WH, Kathrene C, Delwyn C, Glenn EG (2011) Analysis of smoking patterns and contexts among college student smokers. Subst Use Misuse 46(8): 1015-1022.

- Dierker L, Lloyd-Richardson E, Stolar M, Flay B, Tiffany S, et al. (2006) The proximal association between smoking and alcohol use among first year college students. Drug Alcohol Depend 81(1): 1-9.

- Nichter M, Mark Nitcher, Asli C, Elizabeth Lloyd-Richardson (2010) Smoking and drinking among college students: “it’s a package deal”. Drug Alcohol Depend 106(1): 16-20.

- Daley C, Faseru B, Nazir N, Solomon C, Greiner KA (2011) Influence of traditional tobacco use on smoking cessation among American Indians. Addiction 106(5): 1003-1009.