The Problem of Management of Hospital Waste in the Dr Congo: A Vacuum in the Normative and/or Legal Aspect to be Filled

Kasuku Wanduma1*, N Mwabi2, K Lulali3, C Mulaji4, V Mudogo4, M Malumba4 and C Bouland5

1Faculty of Sciences, Free University of Brussels, Europe

2Faculty of Engineering Sciences, University of Lwiro, Africa

3Department of Environment, High School of Social studies, Africa

4Faculty of Sciences, University of Kinshasa, Africa

5School of Public Health, Free University of Brussels, Europe

Submission: April 18, 2017; Published: May 03, 2017

*Corresponding author: Kasuku Wanduma, Faculty of Sciences, Free University of Brussels, Campus de la Plaine, CP.260, Boulevard du Triomphe, 1050 Brussels, Belgium, Europe,Email: kellybaba@yahoo.fr

How to cite this article:Kasuku W, N Mwabi, K Lulali, C Mulaji, V Mudogo, M Malumba, C Bouland.The Problem of Management of Hospital Waste in the Dr Congo: A Vacuum in the Normative and/or Legal Aspect to be Filled. JOJ Pub Health. 2017; 1(5): 555571. DOI:10.19080/JOJPH.2017.01.555571

Abstract

Kinshasa and the rest of the Democratic Republic of Congo (a country in central Africa and a large one) is a trash country when we consider the large quantity of waste piled up in all streams, rivers, pipelines within or outside Several hospitals. By reading the normative or legal framework that deals with the management of hospital waste, none offers the population a healthy living environment. These standards have gaps and inadequacies from the legal point of view, so that both state and private institutions for the management of hospital waste are ineffective and even non-existent. In order to ensure the management of hospital waste, our wish is to update the standards in force and to empower the grassroots entities. If the standards are also binding, the polluter pays principle will apply in the DRC and this will result in the hospital generating a large amount of waste having to assume its responsibilities and pay for the harm caused. And in response, hospitals must apply the principles of sustainable development that will be enshrined in the standards and constitution of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Keywords: Hospital Waste; Legal Vacuum; Bridging; Polluter-Pay; Sustainable Development

Introduction

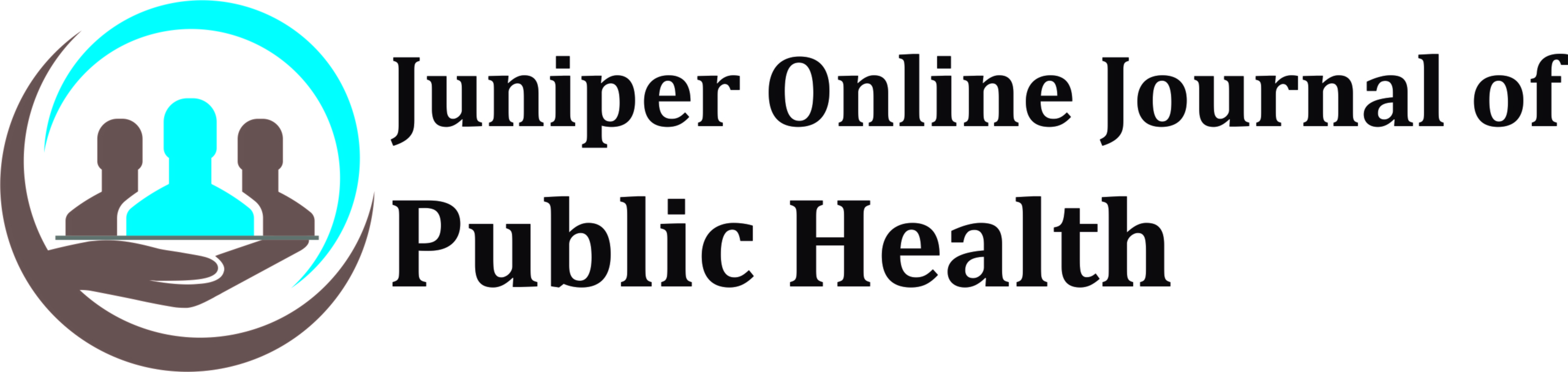

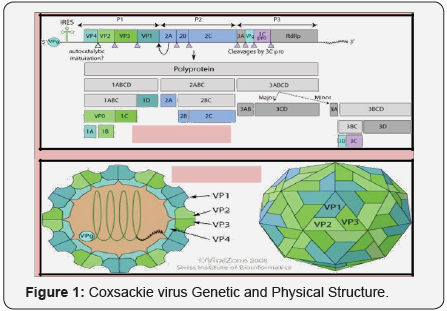

The hospital produced an enormous amount of waste of all kinds. This refers to wastes treated as house hold refuse, wastes from care treated as infectious waste. Thus, in the country like the DRC, hospital waste consists of the set of two DAOM (Waste treated as household waste) + DASRI (Waste from infectious care) as shown in the following (Figures). In view of (Figures 1 & 2) this discharge consists of papers, tourniquet, syringes, leftover food, blood sachets, scalpel, layer of dialysis and incontinent patients, outdated drugs, and other objects that do not deserve To be in this wild dump. We must then specify the terms of our study. Indeed, waste is a few things without values as stated by Larousse Robert. In theory, waste is characterized by the fact that it has become unnecessary in the eyes of its owner and that the owner seeks to get rid of it or has the obligation to discard it. Each product or object we use becomes a waste (when we no longer need it or when it is broken). Waste is therefore a stage in the life of a product and virtually all human activity generates it. Every time we consume a good we produce waste. Indeed, throughout the production chain of an asset, there may be waste, residues, etc.

According to the Decree Law of 15 July 1975 in France supplemented by the Environmental Code, waste is any residue of a process of production, transformation or use of any substance, material, product that its holder intends to use, Abandonment. It then corresponds to any solid, liquid, gaseous or residual substance of a process intenses to be eliminated under the laws or norms in force. The term hospital waste has no legal definition in DRC standards. As no legal definition can guide us, we then call hospital waste, biomedical waste, care waste, Biomedical waste is the result of diagnostic, monitoring and preventive, curative and palliative treatment in the field of human and veterinary medicine [1]. This type of waste is produced by health institutions, medical research and teaching establishments, clinical laboratories or clinical research laboratories.

Let us summarize here the terms related to hospital waste according [2] :

- Hospital waste: all biological or non-biological waste, disposed of with no intention of being used.

- Infectious waste consists of medical waste that can transmit an infectious disease; It is then a sub-category of hospital waste.

- Medical waste is material waste generated by diagnostic or therapeutic procedures in a patient. It is also a sub-category of hospital waste.

Lack of “norms or legal vacuum”, by this term it is necessary to realize or to understand that there are deficiencies, failures in the regulation in this field that concerns the management of hospital waste. It should also be noted that hospital waste is highly infectious and whose disposal methods in the DRC (incineration or burial) affect human health and the environment through air pollution, groundwater pollution, impacts On the health of workers. Thus, this issue pushes the state and the internal and international organizations in the perspective of legislating in this field. For example, in other countries such as France, Belgium, Italy, etc., there is a public health code, as is the Environmental Code, which is a health law legally identifies this issue.

On the other hand, in the DRC and in Africa, we see a legal or regulatory vacuum everywhere. This is enacted by the general scope of the texts which date from the colonial period. This text to the present day is inapplicable for lack of decree of application or hospital hygiene code. As there is a clear vacuum, in the absence of a legal act on the management of hospital waste, its management is lax and anarchic. What will be the consequences? Here then the stakes of such a problematic, this is the objective of our study. Public authorities are responsible or debtor of the populations right to health and healthy environnent. At this level they do not have the right to discharge themselves on hospitals or producers of abundant hospital waste. Their obligation is to set up an appropriate legal framework but also financial, logistical and material resources for its proper management. On the other hand, health professionals are bound by the oath of Hippocrates which asks them not to harm, to remove a harmful effect and to prevent it.

Would mis management of hospital waste from collection to disposal and or final treatment be at odds with this allegiance? The population, workers and health professionals are constantly exposed to pollution, nuisance and large-scale health risks. From a practical point of view we are witnessing irresponsible management of hospital waste in all hospitals and health centers in the DRC. Most hospital structures ignore the basic phases of management from pre-collection, collection, sorting, storage or disposal, to the final treatment of care waste.

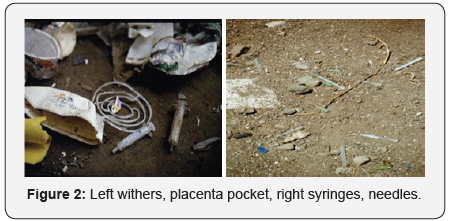

Our findings show that hospital waste is a mixture that is disposed of dangerously either by burial or burning of incineration in defective chambers or in tanks. We know that all its practices have incalculable consequences on human health (with threats of cancer, hepatitis, lung problems) and the environment (by air, soil, Water and olfactory nuisances, etc. (Figures 3 & 4). What is also to be said of the polluterpays principle and producer responsibility. The polluterpays principle is a principle that stems from the ethics of responsibility [3]. Indeed, it is a principle that the costs resulting from measures to prevent, reduce and control pollution must be borne by the polluter [4] and that the attribution of costs associated with pollution control is the responsibility of the polluter. In addition, any waste producer is responsible for its disposal, transport, recovery and, above all, information to the public about its content. The polluter pays principle in view of this definition should be to say that as soon as there is pollution, the originator is asked to assume the monetary consequences of his behavior without any possible derogation. We consider that the hospital should pay for the health damage caused. This principle can only make sense if the damage is repairable or can be repaired. The polluter-pays principle implies that, as the holder of the waste in large quantities, it must bear the cost of destruction [5].

The hospital is held accountable at all stages. We can also apply the principle of producer responsibility in this study. This principle defines the producer of waste as “the person who is the source of the waste”. The supplier shall be deemed to be the holder [6]. This may be the waste producer, the operator of the facility or the person who transports the waste. This concept targets the largest number of actors in the waste sector. The OECD (Organization for Development Cooperation in Europe) is even clearer and specifies that the term producer refers more to manufacturers, importers and producers. The producer of the waste is the one who is the source of the waste (here the care establishments). The regulations lay down the principle of the responsibility of the waste producer, and hence of a health professional (doctor, nurse, biologist, dentist, etc.) with regard to the waste generated during the care provided either in their office or at home Of their patients [7]. It can be the operator of the intermediate storage facility, the waste carrier who are the one holding the waste. This notion is aimed at the greatest number of actors in the disposal sector.

In summary, the principle of polluter pays is a principle - economic efficiency, - incentive to minimize the pollution produced, - and equity. There is then a confusion that demonstrates the legal vacuum that we saw in the standards in the DRC. The principle mentioned above is not known by any healthcare professionals. The sustainable development charter is also a term that we must take into account in standards in the DRC. The principle of sustainable development is an idea based on the links between users and the consequences on the environment. This concept seeks to reconcile economic and social progress with the preservation of the environment in order to meet our present needs without limiting the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. The objective of waste management is summarized in the following: compliance with waste regulations, reduction of environmental impacts through recovery or recycling, avoidance of contamination of personnel, the environment and - of the costs of disposing of hospital waste. To reverse the trend, the only alternative is to fill the vacuum in regulation or legal gaps by a specific law better adapted. Our intervention focuses on several axes by first exposing the inadequate regulation on the management of hospital waste before floors on the more adequate standards.

Methodology

Our study is more bibliographic and investigating the personnel of some hospitals in the DRC. We will dwell on what the law says from the ordinances of the colonial period until what is currently being said in the DRC public health code. On the other hand, we have applied the research-action technique which allows the practitioner that we are, while remaining in contact with the field, to learn to identify his needs and to establish an approach to achieve objectives of change [8]. It encourages a better appreciation of our interventions or to help in the establishment of a code of hygiene. This code will help to leave the legal vacuum towards a binding law for all. What we could do in 2015 by proposing a code of hygiene in the DRC.

Results

Our survey covers a sample of 60 people during the years 2006, 2010 and 2014. It is distributed as follows, 20 doctors from 4 hospitals, 20 nurses from the same hospitals and 20 paramedics. The question was unique: Do you know the standards or laws that govern hospital waste management? Do you know the principle of polluter pays or the principle of sustainable development within the hospitals where you work? The answer for this selected sample shows that approximately 90% (54 people) do not know the principles we listed in our initial question. This sample was selected from a group of people who at least studied because in the DRC there are more illiterates within the care structures, especially in the boys’ group of the rooms and the workers. The application of the principle of sustainable development is not particularly well known:

- The reduction of hospital waste is not everyone’s business because the danger and the risk are not known by the hospital staff due to lack of training and awareness of the waste produced.

- Reuse is also not known in the healthcare environment and is used to renew equipment

- Limiting losses and waste is not everyone’s business. The health care institution does not put in place an approach that limits losses and waste.

- In the initiative for the sustainable management of existing waste, hospitals do not think about on-site composting of organic waste.

- To avoid the consumption of single-use cups, waste must also be reduced in relation to the unique use of certain products and devices. This is not the case in health care facilities in the DRC. This explains a permanent concern for hospital hygiene.

This paragraph allows us to enumerate the legislation in force and then we will see if it is actually applied. The DRC legislation on waste is sparse. These texts are heterogeneous and imprecise. Their updating for me is necessary. They must be popularized and retraining of the magistrates is necessary because many of these standards are obsolete. The inventory of texts on waste in general gives. The ordinance of the 24th of April, 1889, which dates from the colonial period, creating a commission of hygiene in each chief district-place,

- The ordinance of May 10th, 1929, creating in each provincial place a technical direction of the work of hygiene.

- Art 4 and 7 of Ordinance No. 74/345 of 28 June 1959, combining waste management methods and insisting on the protection of sanitation in the city of Kinshasa.

- Ordinance n ° 74/345 of 28 June 1958 on public hygiene in agglomerations.

- Departmental Decree No. 014 / DCNT / CEC / 81 of 17 February 1981 establishing the National Sanitation Service.

- Art n °SC / 0034 / BGV / COJU / CM / 98 of 17 February 1998 implementing measures for environmental sanitation and protection of public health in the city of Kinshasa.

- Finally, in the hospital environment of the DRC, agents do not reduce the waste of consumables like office paper, cartons, ink machines, then it will dematerialize internal orders. So there needs to be an awareness campaign among health professionals for a reuse trick.

The DRC also subscribes to international texts. By way of illustration,

- The Alma Ata Declaration of 1978.

- Basel Chronology on the Control of Border Movements of Hazardous Wastes: 1989 Basel Convention and the Bamako Convention.

- 1992 Helsinki Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes.

The basic text that the legislator of the DRC uses is the act of colonial origin on hygiene and public health. This is Ordinance No. 74/345 of 28 June 1959 on Public Hygiene in Agglomerations, which originated in the organic text of 1926. The characteristic of the first text here is that it was Segregation and only safeguard public hygiene in European agglomerations. On 28 June 1959 this text was repealed and the term “European” was deleted. In 1989, an interdepartmental decree n °120/86 of September 6 modified the latter by adding the public health of cities, urban, commercial, industrial, agricultural, mining and rural agglomerations. With regard to the matter which concerns us in this study, the order of June 28th, 1959, states in point 5 that I shall cite “deposit or cause to be placed in the latrines or in the closed receptacles or in the places designated for this purpose, garbage and any refuse or bury them.

The receptacles shall be placed at the places indicated or authorized by the local territorial authority. They must be emptied on days and possibly at the hours fixed by these authorities. These tanks shall not be allowed to receive any household water or other end of quote. First criticism: the text here does not mention the hospital waste subjects of my study anywhere. This is where we observe the first legal vacuum. Reading the interdepartmental decree n °120/89 of september 6th, 1989 measures only the protection of the public health of the cities but also shows gaps even if the word “waste” appears there without defining it. The innovation of this text is the treatment of domestic waste. It provides the local administrative authorities with the advice of the technician responsible for setting the conditions for the evacuation, burial, incineration or recovery of domestic waste. Article 7 provides for a prohibition of any obstruction of the water drainage channels by any discharges and thus the erection of the constructions above or at a distance of less than twenty meters from the collectors or sewers.

Second criticism of the order cited, the legislation in force is incomplete and has directed this measure towards domestic waste. It is silent on hospital waste and on hospital wastewater, on air pollution and on the pollution caused by liquid effluents in hospitals. No regulation on the urban environment is defined in the legal texts by the legislator in the DRC. The orders of 27 march 1993 and 18 april 1998 concern only measures to improve the environment and protect public health in the city of Kinshasa. Article 4 stresses the construction of the primary and secondary gutters or those which line the roads of urban interest for the occupant of each parcel responsible for maintenance and cleaning of the open gutter. The criticism is that these decrees provide for a penal sanction not applicable and especially nonbinding. As a result, the legislation on this matter is incomplete as it is directed towards domestic waste by remaining silent on hospital, industrial and gaseous waste. The survey we carried out shows that of these hospitals or health center, 80 to 90% presents a significant polluting character because they produce a considerable amount of waste and therefore are big polluters. The same survey shows that these hospital structures do not have a pollution mitigation system or a system for the recovery and recycling of the waste they produce. As the law lapses, enforcement of hospital waste legislation is difficult.

The application of waste legislation only applies to domestic waste, but we also find that it is also empty in its use. Currently, the city of Kinshasa has become an open-air garbage can. We see the multiplication of several vectors (fly, mosquito) and agents that bring various diseases because of this chaotic management of septic tanks, gutters, garbage together with hospital waste. In the gutters there is waste of all kinds (solid waste, syringes, stagnant water, stinks, vehicle oils) (Figure 5), all its waste are gites vector vectors for typhoid fever, malaria For example, cholera, etc. The full septic tanks are emptied as soon as there is rain and even carries leachates from hospitals. The population also benefits from the rain to empty the septic tanks and the excreta are found in the environment. Similarly, household refuse is thrown into gutters or corners of avenues.

All this demonstrates that the law or norms are silent and empty in its application because it does not exist for the hospitals or for the population. On the other hand, the behavior of hospital structures is linked to demographic pressure (factor of deterioration of the health situation in the DRC, followed by an increase in the production of the waste without the infrastructure following the overcrowding [9,10], the development of the informal sector and impunity and immunity (agents who can impose penalties, for reasons of poverty, hospitals or the people of power drive them out when they want to take this kind of people or companies). The development of the informal sector is also the basis for the production of hospital waste. Indeed the economic crisis, unemployment makes that citizen who in a university degree in medicine opens hospitals structures in all the cities and centers of health. They produce waste that they do not know how to evacuate if not buried (buried) or burn them with consequent pollution of air, soil, ground water. In view of this situation, the authorities must intervene in order to assist in the evacuation of all forms of waste. However, its authorities have never developed a standard that is strict and applicable to all. This is another form of impunity and the problem of incompetence.

As regards technical and administrative competence, the period from the colonial period to 1977, the Ordinance of 10 May 1929 had developed a technical direction for hygiene work in each provincial capital under Supervision of provincial governors. Only the royal decree of april 23rd, 1927, had instituted the superior council of colonial hygiene, which was to give its opinion on the sanitary and hygienic questions which the colonial minister would submit, and to study all that might contribute to the preservation Hygiene and public health [11]. This jurisprudence is empty in the context of the management of hospital waste because it only affirms that the superior council of colonial hygiene was the technical adviser of the colonial central administration in matters of hygiene and public health. Its two-person management was concerned only with hygiene and sanitation work related to the problems posed by urbanization. It gave only the lessons on the state of health of the province and of works of public utility. This work was the responsibility of the Ministry of Public Health until 1977, when this service was transferred to the Ministry of the Environment, which was established in 1975.

The mission of this service was also to provide urban sanitation Of the human environment for the control of nuisance caused by the pollution of water, soil and air (Articles 1 and 2 of Ordinance No. 75/231 of 2 July 1975, laying down the powers of the Department of the Environment, Environment, Nature Conservation and Tourism). This ordinance will develop the National Sanitation Program (NAP), which will deal with sanitation and vector control, the disposal of solid and liquid waste, and the cleaning of roads. It follows that in 1977 Waste management is the responsibility of the Ministry of the Environment and PNA becomes a specialized body to be established throughout the national territory. Each municipality imposes environmental services which are reduced simply to the collection of taxes. What about jurisdiction?

The critics who show us this legal vacuum in the standards are multiple.

- First of all, with respect to hospital waste, its ordinances are meaningless.

- The presence of several order centers makes it unclear who will read the law in this matter.

Is the Ministry of Health or the Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Tourism? The parliamentarians or the legislators themselves are not interested in this matter so the directors of the hospitals are limited in their actions. There is a lack of training and awareness of hospital waste. It is then the shortcomings represented by the State in the DRC. Jurisdiction is also ill-defined. Article 9 of the Departmental Order of 6th September 1989 stipulates that courts and tribunals are responsible for determining the law. “Officials of decentralized entities, subregions, zones and local authorities ... and sanitation technicians shall be responsible, in their capacity as a judicial police officer, for infringements of the provisions of this decree”. It is still rare that these officers have means of their competence. In practice, sanitation technicians have no control over hygiene and hygiene texts. This is another gap and / or criticism that we formulate on the colonial texts and after 1977. Thus, the sanctions are hypothetical and Ineffective. For the incineration of hospital waste, the presence of large-scale health and environmental threats is always visible. The legislative gaps in the legislation have as a corollary threats to public health and the environment in which the people of the DRC live. Indeed, the environment is an environment in which the Congolese population functions as a living being. This includes air, soil, natural resources, wildlife and living things. This environment must not be exposed to the effects of poor management of hospital waste which is the basis of pollution and pollution [12].

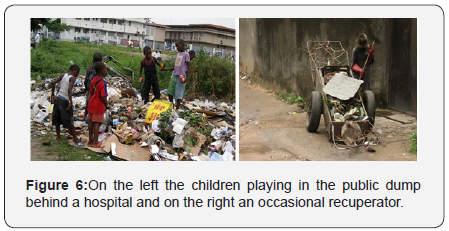

Such pollution involves the supply of smoke from incineration, the burning of hospital waste by producing wind-induced dust, toxic gases and other vectors of disease by inhalation. During the burial of hospital waste, leachate or percolation water is produced which also pollutes the soil, underground and by the technique of leaching after the rivers. All the piping systems in hospital structures serve as deposits for solid and liquid waste (blood, excreta, heavy metals, etc.). Nuisances are accompanied by the destruction of the environment. At this level, the legal vacuum is also to be filled. Concerning human health, the inefficient management of hospital waste is the cause of several diseases in humans which is the first manipulator (from collection to final treatment). Several social categories are exposed (Children and occasional recuperators crisscrossing landfills for examples) (Figure 6).

The paramedics, the sick self-treatment make the purchase of soiled objects badly cleaned like syringes in the parallel market, drugs outdated. Respiratory infections lurk in the hospital chain because of the exposure in garbage corridors of infectious waste. Within the hospital structures, in 2008, there was a rebound of diseases like tuberculosis on 60% of patients, typhoid fever at 87%, cholera as well. These diseases have disappeared in the DRC even in Africa. Our study also aims to challenge the legislator. In order to fight against this problem of hospital waste, the urgent alternative is the adoption of an adapted regulatory framework. An emergency of a regulatory framework: On the one hand our study should help fill the legal vacuum and then also help to update a first code of hospital hygiene in the DRC through public health.

The articles read in the DRC’s regulations are obsolete and do not also legislate on the sensitive aspect of hospital waste. It is for this reason that our work team asks the Ministry of Health in the public health unit to open a study site to urge the Congolese legislator to decide on the legal gaps identified by the law and regulation specific to This type of residue. Actions to be taken:

- defining hospital waste according to field surveys and associating it with the definition of WHO.

- harmonize the management technique as soon as collection, sorting and disposal / treatment.

- train and sensitize hospital managers and the public on the risk/danger of poor management of hospital waste

- provide for a “waste or waste manager and not a service manager” within the hospital structures

- provide colored bins for all waste from food waste, infectious waste, paper, etc. in the healthcare setting.

- the treatment of liquid and other waste before being sent to the recovery and stabilization station.

- store in a more convenient location and avoid scavengers from accessing secure premises and allowed only to authorized personnel.

- Provide a route for collection and use specialized vehicles to the hospital waste treatment and disposal site.

- prohibit by regulation any form of disposal (landfill, burning, burial) that is not regulated, wild incineration and consider poles or units of incinerators from each hospital structure.

This regulation must be applicable to all health professionals, visitors, accompanying persons, patients ... who would leave a health post for another sector. The legislator will enact civil, criminal, moral, ethical and ethical sanctions. In this way compensation mechanisms will have to be created within the national order of doctors or in the national bank of the DRC. To reinforce its rules, it is desirable to integrate them in the code of public health of the DRC which would be the “code of hygiene of the Democratic Republic of Congo”.

As part of the action research that is the technique applied in our study, we proposed at the end of this study in April 2015 the code to the Ministry of Public Health which has under its tutelage hospital structures. The code should be couched in the form of the law and published in the official Gazette of the DRC. At Title I level, the general provisions of the Code are set out in Chapter II, Art. 3 concerning the definitions of waste as well as biomedical waste, infectious care activities and other articles as Article 16 Handling, 21 re-use and recycling in art 22, 27 for waste treatment and 30 for recovery, 34 for anatomical waste and 35 to 37 for sharps waste, pharmaceuticals and special waste. We have proposed articles on the hygiene of health facilities with 6 articles and in paragraph 2 the management of biomedical waste at the place of production (Art 23 to 28) The biomedical waste transport system is disclosed in paragraph 2, And paragraph 3, Articles 30 and 32 deal with the treatment of biomedical waste.

The authors’ obligations are recorded in Articles 33-38. Also wanted to put what we call the Sustainable Development Charter into the five guiding principles within the hospital environment. But this could not have existed in the text. The objective is to assess objectively the performance of hospitals in terms of sustainable development (guiding principle1). In the guiding principle2, we anticipate that the hospital can integrate sustainable development issues into the professional practices of health actors. Guiding Principle 3 provides that the hospital structure can evaluate sustainable development issues in projects and decision-making processes. Guiding Principle 4 was to amplify training programs and actions to sensitize staff to the challenges of sustainable development in hospitals. And finally, guiding principle 5 would allow the integration of sustainable development performance criteria into hospital management.

As stated above, health institutions would commit themselves to developing actions in the field of steering sustainable development by extending to me a committee to draw up its plans, doing eco-renovation at all levels, Optimized management of all, by continuing the mastery in the management of hospital waste. Its establishments will also privilege the policy of smart purchases and communication, training on sustainable development.

These are part of the process of developing the polluter-pays principle within the hospital. In our study, we assumed that the Ministry of Health, which will now have power over hospitals, will ask the legislator to put its articles in the constitution into binding law. The legal vacuum to this day still persists as the picture taken in 2017 in a hospital in the DRC shows (Figure 7). If the hospital hygiene code were applicable, the images in the (Figure 7) will no longer show this image of the hospital which mixes in the same trash bin under a lever in a patient room: - tigettes, blood on wadding, chalises, Pampers with incontinence (urine) of patient housed in this room. It is also diabetic, the boxes of drugs in their carton; Bottles, papers, food (fruit fines). This confirms our definition of hospital waste (DAOM and DASIR) Our team will continue its awareness campaign in this field among all health professionals in the DRC and that the legislator can also follow and make the law binding. For us the legal vacuum is still there despite the experts of the Ministry of Public Health who followed our recommendations.

Conclusion

The study reveals a failure of the hospital waste management system from a legal point of view, which explains why we have just noted the gap in our responses to the first question. The texts in force are incomplete and unregulated in terms of treatment of all waste in the DRC and shows several harms linked to several centers of ordering (Ministry of Health and Environment). Legislators must intervene to ensure that these shortcomings are quickly addressed. Rather, it has taken as a basis the guiding text of the colonization of a decentralized system to manage waste in general. This text is instituted by the Ministry of the Environment which has demonstrated its inefficiency following its centralism.

No hospital structure visited makes any effort or plans to follow the law on biosafety to be established with regard to hospital waste. It is then time that the authority can take its skills especially success will depend only this law as we just initiated in the form of hygiene code DRC hospital. This text, which should be promulgated in 30 days following article 159, after we have incited the Minister of Health to its application, is still not sunk to date in the official journal of the DRC under the law or Legal standard. It will be necessary for the judicial institutions to ensure the application of the texts by obliging the producers to pay taxes linked to their packages. Subsequently, judicial officials should be trained to provide training in environmental criminal law to police officers, students and magistrates who can obtain a diploma or environmental certificate. The objective is to make the DRC police officers who will crack down on the recalcitrant in waste management of all kinds. All the principles charters of sustainable development cited are to be inscribed in the constitution in its preamble so that the DRC has a power over its population. In order to combat the effects of mismanagement, the DRC needs to have an adequate legislative framework, which refers to the development of standards, but also to insist on the hospital hygiene code under the supervision of the Minister of Health. the health. Our wish is that the public power will focus on training and awareness of all the actors involved because health at a price. Efforts must be made together to avoid the factors that threaten our health and finally to assert that health and the environment are linked.

Acknowledgement

To the hospitals and health center that have collaborated in our study as well as the photographer who has cooled in image our surveys.

References

- WHO (1999) Safe management of waste from healthcare activities. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 77.

- Daumal F (2012) Dechets hospitaliers : les problemes sont ils resolus. Colloque Hopital D Amiens, France.

- Pigou AC (1920) The economics of welfare. (4th edn), Mac Millan and Co, London, Uk, pp. 551.

- De Sadeller N (1999) Les principes du pollueur-payeur, de prevention et de precaution, Essai sur la genese et la portee juridique de quelques principes du droit de l environnement. Manuels universitaires, France, pp. 437.

- Vendure C (2009) Gestion des dechets protection de l’environnement et responsabilite, RGAR, France.

- Davidson Ad Michael (1988) The Brundtland Challenge ans the cost of inaction. Institute For Research on public policy, Canada, USA, pp. 159p.

- Kaczmarek B (2009) Gestion des dechets hospitaliers, Dechets et Developpement Durable, CHRU de Lille, Journee EHPAD, Europe.

- Michele C (2002) Introduction a la recherche-action : modalite d une demande theorique centree sur la pratique. Cahiers de l Apliut 21(3): 8-20.

- Nzuzi L (1989) Urbanisme et amenagement en Afrique noire, SEDES (edn), Paris, pp. 247-248.

- Dindoye DP (1985) Problematique de l Habitat Urbain, Zaire-Afrique, Fevrier, Africa, pp. 162.

- Munene yy (1999) La problematique de la gestion des dechets a Kinshasa : aspect normatif et institutionnel. Med Fac 64(1): 237-246.

- Mbengue MF (1998) Dechets biomedicaux en Afrique de l ouest, problemes de gestion et esquisse de solution, IAGU, Africa.