Provider Perceived Colorectal Cancer Screening Barriers: Results from a Survey in Accountable Care Organizations

*Hongmei Wang1, Abbey Gregg1, Fang Qiu2, Jungyoon Kim1, Lufei Young3 and Jiangtao Luo2

1Department of Health Services Research and Administration, Omaha, USA

2Department of Biostatistics, Omaha, USA

3Department of Physiological and Technological Nursing, Omaha, USA

Submission: February 15, 2017; Published: February 27, 2017

*Corresponding author: Hongmei Wang, Department of Health Services Research and Administration, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Public Health, 984350 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, 68198-4350, Tel:(402)559-9413; Email: hongmeiwang@unmc.edu

How to cite this article: Hongmei w, Abbey G, Fang Q, Jungyoon K, Lufei Y, et al. Provider Perceived Colorectal Cancer Screening Barriers: Results from a Survey in Accountable Care Organizations. JOJ Pub Health. 2017; 1(2): 555557. DOI: 10.19080/JOJPH.2017.01.555557

Abstract

Colorectal Cancer (CRC) screening is vital to reduce CRC motility rate and primary care providers (PCP) play an essential role in promoting CRC screening. This study examines the CRC screening barriers perceived by PCPs and their associations with provider characteristics and practice features using data collected through a survey administered in fall 2015 to all PCPs from thirteen Accountable Care Organization clinics in Nebraska. The PCPs were asked to rate the significance of twelve patient, provider, and system-related barriers. Bivariate analyses were conducted to examine the differences in the providers’ perception by provider age, gender, credential, practice experience, workload, and clinical practice indicators. PCPs from ACO clinics perceived that barriers for CRC screening were mainly at the patient-level, fear of discomfort/pain and financial barrier in particular, rather than provider-level or system-level. Very few providers agreed that lack of provider recommendation was a major barrier to CRC screening. However, bivariate analyses results show that providers from clinics without a protocol or reminder system on CRC screening and providers reviewed cancer screening performance reports less frequently were more likely to report that a lack of a reminder system could be a major barrier. In addition, nurse practitioners and physician assistants were more likely to report that patients’ lack of awareness about screening is a major barrier than physicians. Based on the providers’ perception, policies targeting changing patients’ financial barriers and their fear of discomfort may be most effective to promote CRC screening.

Abbreviations: CRC: Colorectal Cancer; PCP: Primary Care Providers; ACO: Accountable Care Organization; EMR: Electronic Medical Records; PCMH: Patient-Centered Medical Home; SERPA-ACO: South-Eastern Rural Physician Alliance Accountable Care Organization

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death for both men and women [1]. The prevention and early detection of CRC through screening has led to a large reduction in colorectal cancer incidence and death [1]. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening adults aged 50-75 years of age for CRC using fecal occult blood test yearly, sigmoidoscopy every five years, or colonoscopy every ten years to reduce colorectal cancer mortality [2]. However, over 30% of adults aged 50-75 years have not been screened for CRC according to national guidelines [3]. In particular, rural residents have been found to be less likely to receive timely and appropriate CRC screening according to these guidelines [4-6]. Identifying barriers to increase appropriate CRC screening, especially for rural residents, should be a research priority.5The purpose of this study is to examine the CRC screening barriers perceived by PCPs and their associations with provider characteristics and clinic practice indicators (Table 1).

Quantitative studies have shown that barriers to CRC screening included being Hispanic ethnicity or African American race, female gender, being in the younger age range of screening guidelines, lower income, low literacy and education levels, and lack of health insurance [6-9]. Being married, having an increased perceived risk of CRC, having a usual source of care, and having routine health exams are associated with increased CRC screening rates [6-9]. Provider’s [7-9] gender, specialty, and years of practice experience, are found to be related to their patients’ screening behaviors [7-9]. Particularly, physician discussion with their patients on screening needs are found to be associated with increased screening and the most commonly reported provider-level barrier to CRC screening is the lack of screening recommendation [7-9].

Barriers to CRC screening are complex and related to both patients’ and providers’ attitude, knowledge, motivation, and ability.10Studies conducted through surveying or interviewing providers and patients also show that the cost of CRC screening and embarrassment or fear about the procedure are also frequently reported patient barriers for CRC screening [10- 18]. These studies also confirm that the lack of physician recommendation is a major barrier for the patients to get CRC screening [11,13,17]. Additionally, modifiable providerlevel barriers to screening include lack of provider time to discuss screening options with patients due to high volume or prioritizing of other health issues [18-19]. On the other hand, using reminder systems, offering office-based screenings and using good communication skills could increase CRC screening rates [18,19]. The supply of specialists (e.g., gastroenterologist or endoscopic capacity) is also found to be positively associated with CRC screening [20].

A body of literature have examined barriers of CRC screening in rural populations and have identified similar barriers for CRC screening at the patient and provider level [21-24]. Rural-urban comparison studies suggest that rural communities place less importance on individual health and preventive services. Rural patients are less likely to have routine preventive visits and less likely to receive physician recommendations for CRC screening than urban residents [25,26]. Studies also indicate that rural patients are more likely to perceive screening costs as a barrier than urban patients [27,28]. Rural residents are less likely to believe that CRC can be prevented and that regular screening will decrease their level of worry about illness; however, rural residents more strongly feel that a CRC diagnosis will change their whole lives [28]. Previous studies suggest that primary care providers play an essential role in promoting CRC screening and patients cited physician recommendation as the one of the most important facilitators for screening. Rural residents are more likely to report having a health care provider but report fewer visits to health care providers [29]. It is thus important for us to understand whether rural patients experience certain barriers that are not common to urban residents, in particular related to their interactions with physicians.

This study takes a unique perspective by surveying PCPs from thirteen Accountable Care Organization (ACO) clinics on their perceived barriers for CRC screening. ACOs were established under the Medicare Shared Savings Program, which consist of a group of medical providers worked together to improve quality of care and lower health care costs [30,31]. ACOs that meet performance benchmarks may share in cost savings that result from providing quality care efficiently for Medicare patients. ACO clinics create opportunities to improve cancer screening through practices emphasizing coordinated care, use of electronic medical records (EMR), and performance on preventive quality measures. Particularly, a majority of the ACO clinics included in this study locate in rural communities. The study findings can help identify barriers to and facilitators of CRC screening from the perspective of PCPs practicing in ACO clinics and their perceptions are mostly relevant to rural patients. The barriers and facilitators of CRC screening identified in this study also shed light on designing strategies specific to rural patients.

Methods

To evaluate the central macular microvascular network in patients with maculartelangiectasia type 2 (MacTel2) using Swept Source optical coherence tomography Angiography.

Patient and Method

Study setting

The survey was conducted in thirteen primary care clinics within an advance payment ACO supported by the Medicare Shared Savings program in Nebraska. The ACO received Medicare funding to set up the tracking and reporting infrastructure for reporting measures of quality including cancer screening indicators. The majority of these clinics were located in rural counties in Nebraska and ranged in size from four to fifteen primary care providers. All of the ACO clinics have received or are working on completing patient-centered medical home (PCMH) certification, have adopted EMR systems, have a protocol for reaching out to patients due for CRC screening, and receive a quarterly performance report on quality measures including CRC screening. Each clinic either has physicians that perform colonoscopy or is located in a town with a facility that provides colonoscopy services. More details about study setting are described in a previous study [32].

Data

The survey data were collected from a total of 93 PCPs, including physicians, physical assistants, and nurse practitioners, in thirteen clinics. The overall response rate is 86%. The survey was administrated in fall 2015 by pencil-paper format, and took approximately 20 minutes to complete. The survey questions included provider demographics, credentials, practice history, and their clinic practices on CRC screening: whether they have a protocol to reach patients, whether they have a reminder system on CRC screening, and how frequently they review quality performance report. The PCPs’ practice during wellness visit and episodic visits in terms of their discussions with patients on CRC screening and perceived barriers for colorectal cancer screening were also asked. Twelve CRC screening barriers related to patients, providers, and health systems were identified in the literature [10,14]. For all CRC screening barriers identified, PCPs were asked to rate them from least significant (1) to most significant (5) on a scale from 1 to 5.

Measures

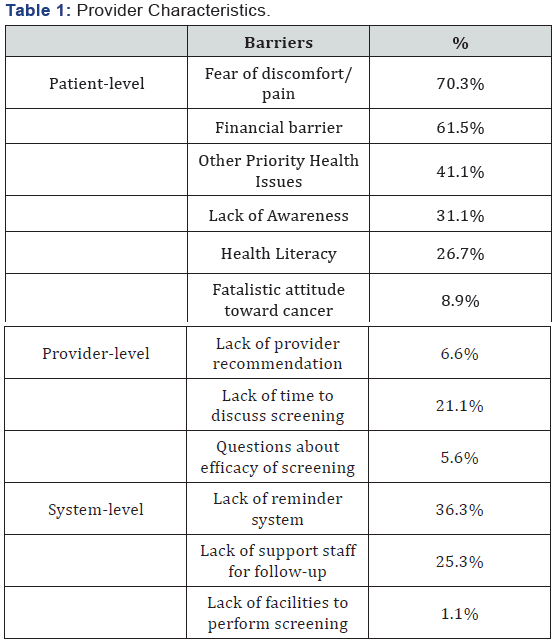

The percentages of providers perceiving a CRC screening barrier as significant (4 or 5) were calculated and used as the main outcomes of interest of this study. Patient-level barriers included Fear of discomfort/pain, financial barrier, other priority health issues, Lack of awareness, Health literacy, Falistic attitude toward cancer. Provider-level barriers included Lack of provider recommendation, Lack of time to discuss screening, and Questions about efficacy of screening. System-level barriers included lack of reminder system, lack of support staff for followup, lack of facilities to perform screening.

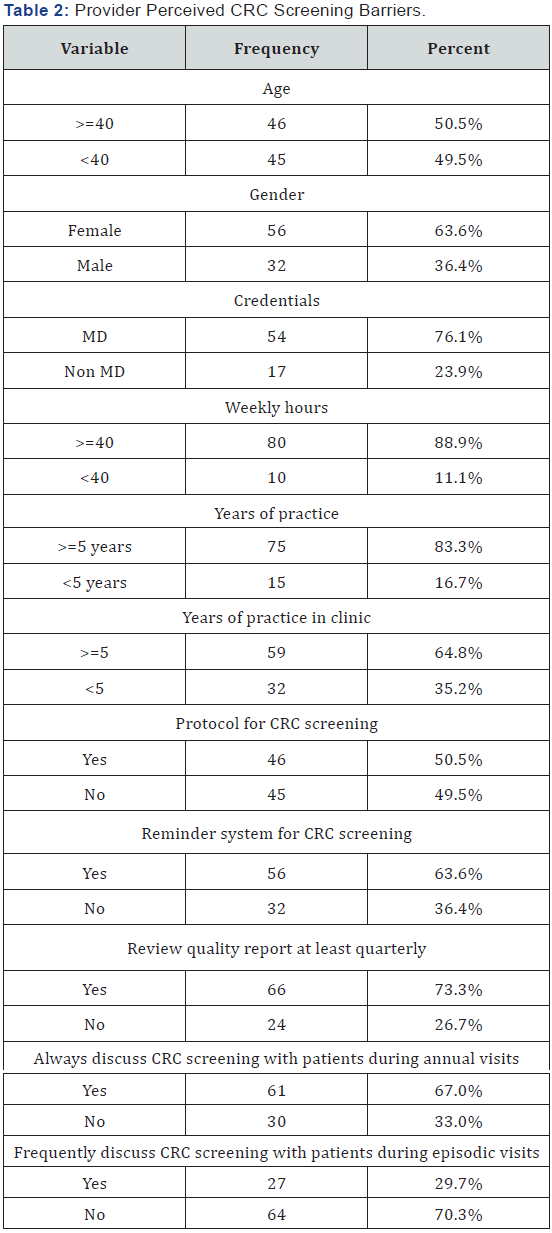

Provider demographics included provider age (>=40, <40 years), gender (female, male), credentials (MD, non-MD), workload (weekly hours >=40, <40), years of practice (>=5, <5 years), and years of practice in current clinic (>=5, <5 years). Provider clinic practice indicators included Protocol for CRC screening (Yes, No), Reminder system for CRC screening (Yes, No), Review quality report at least quarterly (Yes, No), Always discuss CRC screening with patients during wellness visits (Yes, No), and Discuss CRC screening with patients during episodic visits frequently (Yes, No).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the participating PCPs were examined. The percentage of PCPs perceiving a CRC screening barrier as significant was reported across all twelve patient, provider, and system-related barriers. Bivariate analyses were also conducted, where Chi-square tests or Fisher Exact tests were used to examine the differences in the providers’ perception by provider age, gender, credential, practice experience, workload, and clinic practice indicators.

Results

Analysis

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the providers who responded the survey. About half of the PCPs aged 40 years and above; 36% of them were female. About 76% had a medical doctor degree; most of them worked more than 40 hours a week (89%); 83% had over 5 years of practice experience; and 65% had over 5 years of practice experience in the current clinic. Although all ACO clinics had a protocol to reach out to patients for colorectal cancer screening, and have a reminder system through EMR system or care coordination team, and provide quarterly quality performance report, only about half of the PCPs responded knowing the CRC screening protocol, 64% knowing the CRC screening reminder system, and 73% reported reviewing the quality report at least quarterly. In addition, about 67% of the PCPs reported always discussing CRC screening with their patients during annual wellness visits. About 27% of the PCPs reported they frequently discuss CRC screening with their patients during episodic visits.

Provider perceived barriers

The most commonly reported patient barriers were fear of discomfort/pain and financial barrier. About 70% of the PCPs considered that patients’ fear of discomfort or pain was a significant (level 4 or 5 out of a scale of 5) barrier for CRC screening. About 62% of the PCPs considered the financial barrier was a significant barrier for patients to get screened. Following the two top barriers, other prioritizing health issues (41.1%), lack of awareness (31.1%), and health literacy (26.7%) were reported as significant barriers by some participating PCPs. Very few providers considered fatalistic attitude toward cancer (8.9%) was a major barrier to CRC screening.

Not many PCPs considered the identified provider-level barriers were major deterrents for screening. Only about 21% PCPs reported that a lack of time to discuss screening with patients was a barrier. Even fewer providers agreed that lack of provider recommendation (6.6%) or questions about efficacy of screening (5.6%) was a major barrier to CRC screening. The majority of providers did not think that the identified system barriers were significant barriers to screening. Of the three identified system barriers, lack of reminder system (36.2%) was considered as a significant barrier by most PCPs, followed by lack of support staff (25.3%). Only 1% of the PCPs think facility shortage was an issue for CRC screening.

Provider perceived barriers by provider characteristics

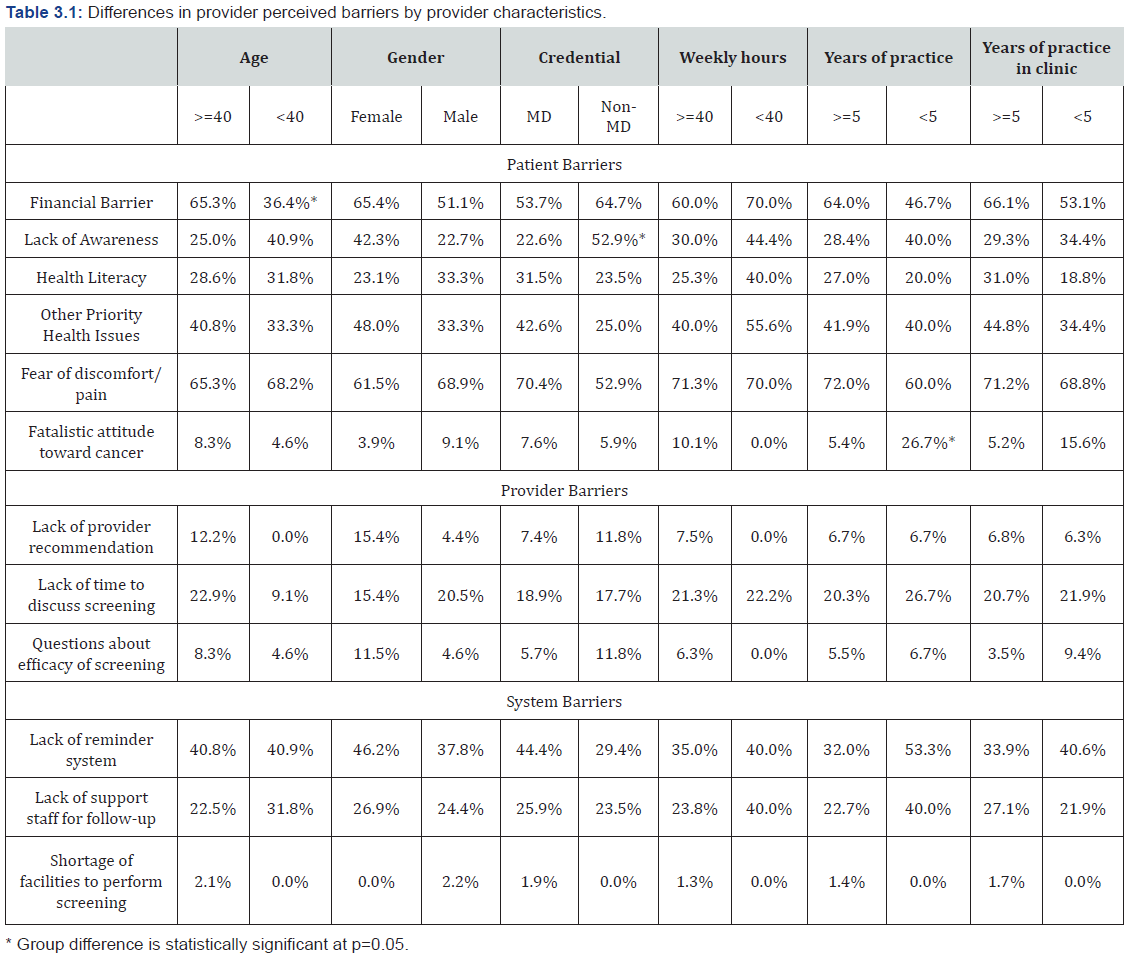

Table 3.1 shows the bivariate analysis results on the association between provider characteristics and perceived behaviors. Chi-square tests and Fish-exact tests results suggest that perceived barriers were not significantly related to provider gender, practice, or workload but varied by providers’ age and credential. Specifically, providers aged 40 years or older were more likely to report that finances were a barrier for patients than younger practitioners (65% vs. 36%, p=.02). Nurse practitioners and physician assistants were more likely to report that patients’ lack of awareness about screening is a major barrier than physicians (53% vs. 23%, p=.02). Providers that had less than 5 years of practice experience were more likely to consider fatalistic attitude toward cancer was a significant barrier for screening (27% vs. 5%, p=0.03). No significant associations with provider characteristics were identified in the bivariate analysis regarding other CRC screening barriers.

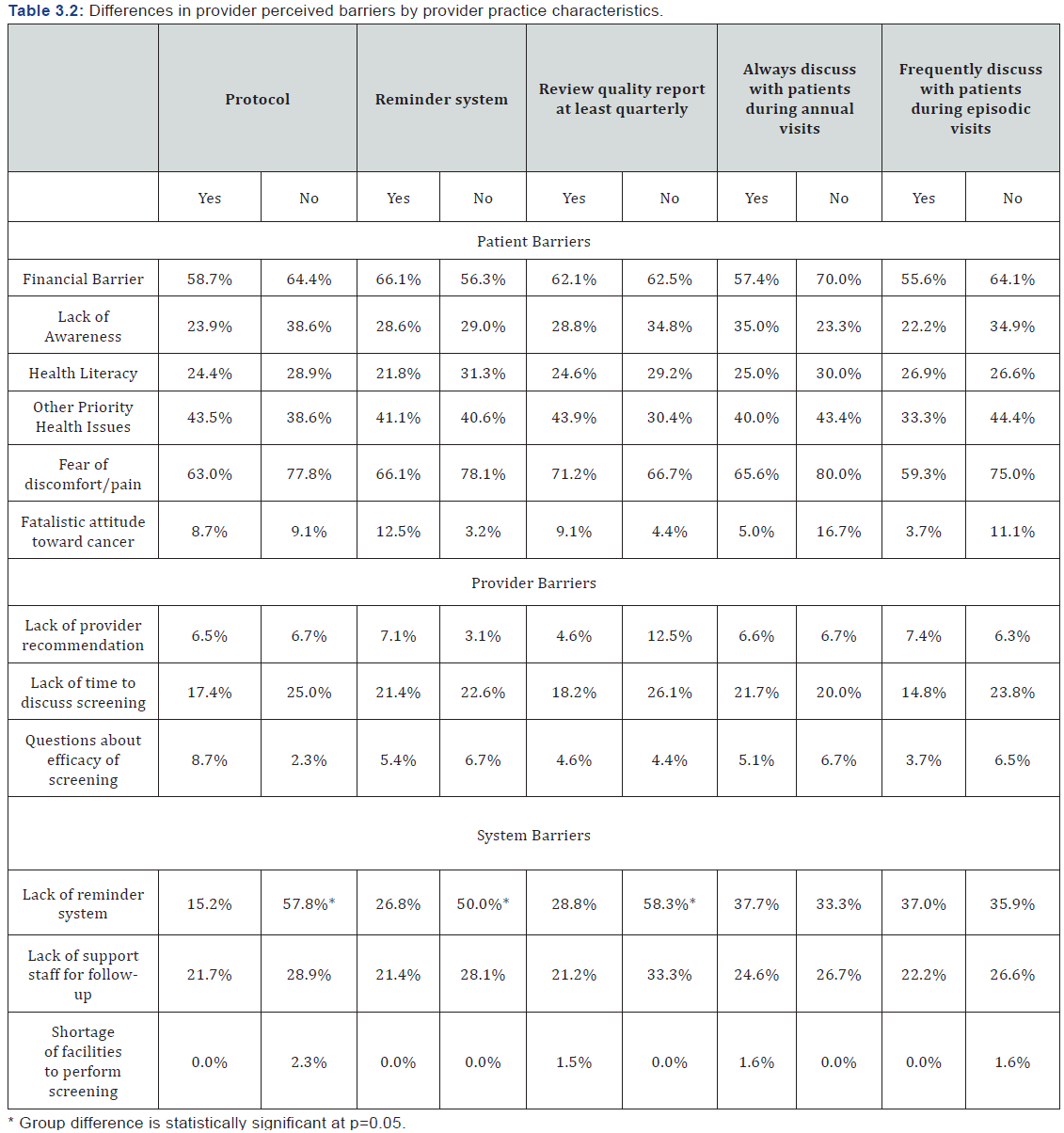

Table 3.2 shows the bivariate analysis results on the association between provider clinical practice indicators and perceived barriers. Providers that reported reviewing cancer screening performance reports less frequently (58% vs 28%, p=.01), not having a CRC screening protocol (58% vs 15%, p<.01), or not having a CRC screening reminder system (50% vs 27%, p=.03) in clinic were more likely to report that a lack of a reminder system is a major barrier for CRC screening. No significant associations with clinical practice indicators were identified in the bivariate analysis regarding other CRC screening barriers.

Discussion

Primary care providers from ACO clinics perceived that barriers for CRC screening were mainly at the patient-level. Patients’ fear of discomfort/pain and financial barrier were the two patient-level barriers considered by most providers as significant. This finding is consistent with previous studies examining barriers of colorectal cancer screening perceived by primary care providers.10-18 Patients’ fear of discomfort or pain is mostly related to endoscopy procedures and was often reported as a deterrent for CRC screening. Financial barriers are often related to lack of insurance of the patients and even for those with insurance coverage there is confusion on the payment of a screening colonoscopy versus a diagnostic colonoscopy. Although the Affordable Care Act requires screening colonoscopy is covered by all insurance policies, for those tests finding and removing polyps during the procedure copayment may be incurred and which leads to financial concerns. Bivariate analysis results show that PCPs aged 40 years or older (65%) were more likely to consider financial barrier a significant barrier than those younger than 40 years. The financial barriers and patients’ fear of the test continue to be perceived as the top barriers for CRC screening, especially in rural areas [33]. Future efforts needs to take into consideration effective strategies to tackle these issues.

An interesting finding at the provider-level is that only 7% of the providers considered lack of physician recommendation were a barrier. Previous studies have shown that physician recommendation is positively related to cancer screening outcomes and is also considered a major barrier for cancer screening, especially in rural settings [16-24]. A detailed examination of the literature shows that PCPs and patients may have different perceptions on CRC screening barriers. Patients are more likely to consider physician recommendation as the top facilitator of screening and the lack of which is associated with worse screening outcomes; while physicians stress patient financial barriers and lack of awareness and fear of pain as main barriers [16,17]. This finding of this study seem to be in line with the physician identified barriers in the literature. However, it could also show that the ACO PCPs surveyed were confident in providing recommendation to patients on CRC screening and did not consider this is a barrier in the ACO clinic setting. Caution needs to be taken to properly interpret the implications of this finding and its application in the field.

Among the system-level barriers, a lack of a reminder system was perceived the most significant by the ACO PCPs (36%). Particularly, a larger proportion of the providers from a clinic without a protocol (58%), or or reminder system on CRC screening (50%), or did not review performance report at least quarterly (58%) perceived that lack of a reminder system could be a major barrier. The combined findings suggest that providers did not perceive lack of a reminder system was a problem because a reminder system was already in place in their clinic. Providers in general believed that having a reminder system was effective strategies to help promote patient cancer screening and a lack of a reminder system would be a barrier. Although the protocol, a reminder system, and performance reports on CRC screening were available in participating clinics, there were a fair number of PCPs who were not aware of these measures. This also shows that a patient-centered medical home structure and existence of care coordination team may not be sufficient to change physician perception and clinic practices, as found in some previous studies [34,35].

The barriers and facilitators of CRC screening identified in this study also shed light on designing strategies specific to rural patients as the majority of the participating clinics are in rural communities. The study findings do not seem to suggest major differences in identified barriers specific to rural patients. The fatalistic attitude toward cancer was considered as a special feature for rural patients. However, only a few of the PCPs considered it as the barriers for CRC screening. We do not rule out the possibility that although rural patients may have similar barriers to CRC screening to those of their urban counterparts, the relative significance of barriers may vary in different settings and our study did not attempt to explore the relative importance. For example, cost of screening and physician recommendation may be common barriers to both rural and urban patients, but previous studies have found that rural patients are less likely to receive physicians’ screening recommendation and more likely to report cost as a barrier than urban patients [26,28]. While continuing expand access to care for this population is helpful, additional efforts are needed to improve patients’ knowledge and attitudes to increase compliance to CRC screening guideline. More proactive approach to increase communication between providers and rural patients could be one of the ways to improve patients’ knowledge and reduce misconception on CRC screening.

This study has several limitations. A major limitation of this study is the generalizability of the study findings. This study focus on examination of barriers and facilitators of CRC screening perceived by PCPs from ACO clinics, most of which are in rural settings. These ACO clinics have adopted certain measures that may not have been prevalent in other primary care clinics, such as the use of EMRs, a protocol for CRC screening, care coordination efforts to remind PCPs about screening status, and the provision of quarterly performance reports. Although the major findings are consistent to what literature suggests, caution needs to be taken to generalize the study results that are particular to rural or ACO settings to a larger context. Second, all possible barriers may not have identified. PCPs were asked to rate on twelve most frequently reported barriers and were not provided a chance to report a significant screening barrier at the survey administration. Third, this study also focused on PCPs’ perception on CRC screening barriers and did not have measures for patients’ attitude toward and perception of CRC screening barriers. Patients’ perception may be different from PCPs as suggested in the previous studies and our understanding on the CRC screening barriers will be more complete with information on the patients’ attitude, knowledge, and beliefs. Fourth, providers’ race and ethnicity may be associated with their perception of CRC barriers but we do not have this information for all participating PCPs. Of those PCPs that we had their race and ethnicity information, the majority of them were non- Hispanic white. Lastly, this study had a relatively small sample size. Although response rate was relatively high at 86%, the small sample size did not allow for multivariate analysis exploring the joint influence of multiple factors on perceived barriers.

Conclusion

Based on the providers’ perception, policies targeting changing patients’ financial barriers and their fear of discomfort may be most effective to promote CRC screening. However, caution needs to be taken to understand that providers’ perception may be different from patients’ perception. Barriers perceived by PCPs need to be combined with patients reported barriers and barriers identified based on medical or claims data to build a complete picture and inform policy decisions. Future interventions at the clinic level need to consider providers’ attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions. Evidence-based strategies such as provider reminders and continued provider education may be promising interventions.

Acknowledgement

The study was funded jointly by the UNMC College of Public Health and Fred and Pamela Buffett Cancer Center grant. We also would like to express our appreciation to South-Eastern Rural Physician Alliance Accountable Care Organization (SERPA-ACO) for their support for data collection and survey administration.

References

- American Cancer Society (2014) Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2014-2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Colorectal Cancer Screening Guidelines.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) Vital signs: Colorectal cancer screening test use - United States, 2012 62(44): 881- 888.

- Yannuzzi LA (2010) The Retinal Atlas. Elsevier, Oxford, Saunders, London.

- Anderson AE, Henry KA, Samadder NJ, Merrill RM, Kinney AY (2013) Rural vs urban residence affects risk-appropriate colorectal cancer screening. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 11(5): 526-533.

- Cole AM, Jackson JE, Doescher M (2012) Urban-rural disparities in colorectal cancer screening: cross-sectional analysis of 1998-2005 data from the Centers for Disease Control’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Study. Cancer Med 1(3): 350-356./a>

- James TM, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, Feng C, Ahluwalia JS (2006) Disparities in colorectal cancer screening: a guideline-based analysis of adherence. Ethn Dis 16(1): 228-233..

- Guessous I, Dash C, Lapin P, Doroshenk M, Smith RA, et al. (2010) Colorectal cancer screening barriers and facilitators in older persons. Prev Med 50(1-2): 3-10.

- Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA (2008) Predictors of colorectal cancer screening behaviors among average-risk older adults in the United States. Cancer Causes Control 19(4): 339-359.

- Weiss JM, Smith MA, Pickhardt PJ, Kraft SA, Flood GE, et al. (2013) Predictors of colorectal cancer screening variation among primarycare providers and clinics. Am J Gastroenterol 108(7): 1159-1167.

- Jones RM, Devers KJ, Kuzel AJ, Woolf SH (2010) Patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening: A mixed-methods analysis. Am J Prev Med 38(5): 508-516.

- Dulai GS, Farmer MM, Ganz PA, Bernaards CA, Qi K, et al. (2004) Primary care provider perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening in a managed care setting. Cancer 100(9): 1843-1852.

- Nichols C, Holt CL, Shipp M, Eloubeidi M, Fouad MN, et al. (2009) Physician knowledge, perceptions of barriers, and patient colorectal cancer screening practices. Am J Med Qual 24(2): 116-122.

- Jones RM, Woolf SH, Cunningham TD, Johnson RE, Krist AH, et al. (2010) The relative importance of patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening. Am J Prev Med 38(5): 499-507.

- Meissner HI, Klabunde CN, Breen N, Zapka JM (2012) Breast and colorectal cancer screening: U.S. primary care physicians’ reports of barriers. Am J Prev Med 43(6): 584-589.

- Knight JR, Kanotra S, Siameh S, Jones J, Thompson B, et al. (2015) Understanding barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Kentucky. Prev Chronic Dis 12: 140586.

- Klabunde CN, Vernon SW, Nadel MR, Breen N, Seeff LC, et al. (2005) Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of reports from primary care physicians and average-risk adults. Med Care 43(9): 939- 44.

- Hoffman RM, Rhyne RL, Helitzer DL, Stone SN, Sussman AL, et al. (2011) Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: Physician and general population perspectives, New Mexico, 2006. Prev Chronic Dis 8(2): A35.

- Feeley TH, Cooper J, Foels T, Mahoney MC (2009) Efficacy expectations for colorectal cancer screening in primary care: Identifying barriers and facilitators for patients and clinicians. Health Commun 24(4): 304-315.

- O Malley AS, Beaton E, Yabroff KR, Abramson R, Mandelblatt J (2004) Patient and provider barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the primary care safety-net. Prev Med 39(1): 56-63.

- Stimpson JP, Pagan JA, Chen LW (2012) Reducing racial and ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer screening is likely to require more than access to care. Health Aff (Millwood) 31(12): 2747-2754.

- Greiner KA, Engelman KK, Hall MA, Ellerbeck EF (2004) Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in rural primary care. Prev Med 38(3): 269-275.

- Tessaro I, Mangone C, Parkar I, Pawar V (2006) Knowledge, barriers, and predictors of colorectal cancer screening in an Appalachian church population. Prev Chronic Dis 3(4): A123.

- Young WF, McGloin J, Zittleman L, West DR, Westfall JM (2007) Predictors of Colorectal Screening in Rural Colorado: Testing to Prevent Colon Cancer in the High Plains Research Network. J Rural Health 23(3): 238-45.

- Wilkins T, Gillies RA, Harbuck S, Garren J, Looney SW, et al. (2012) Racial disparities and barriers to colorectal cancer screening in rural areas. J Am Board Fam Med 25(3): 308-317.

- Rosenwasser LA, McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Weisman CS, Hillemeier MM, Perry AN, et al. (2013) Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among women in rural central Pennsylvania: Primary care physicians’ perspective. Rural Remote Health 13(4): 2504.

- Davis TC, Rademaker A, Bailey SC, Platt D, Esparza J, et al. (2013) Contrasts in rural and urban barriers to colorectal cancer screening. Am J Health Behav 37(3): 289-298.

- Hawley ST, Foxhall L, Vernon SW, Levin B, Young JE (2001) Colorectal cancer screening by primary care physicians in Texas: A rural‐urban comparison. J Cancer Educ 16(4): 199-204.

- Hughes AG, Watanabe-Galloway S, Schnell P, Soliman AS (2015) Ruralurban differences in colorectal cancer screening barriers in Nebraska. J Community Health 40(6): 1065-1074.

- Larson SL, Fleishman JA ( 2003) Rural-Urban Differences in Usual Source of Care and Ambulatory Service Use Analyses of National Data Using Urban Influence Codes. Med Care 41(7 Suppl): III65-III74.

- MacKinney AC, Mueller KJ, McBride TD (2011) The march to accountable care organizations—how will rural fare? The J Rural Health 27(1): 131-137.

- McClellan M, McKethan AN, Lewis JL, Roski J, Fisher ES (2010) A national strategy to put accountable care into practice. Health Aff (Millwood) 29(5): 982-990.

- Young L, Kim J, Wang H, Chen LW (2015) Examining factors influencing colorectal cancer screening of rural Nebraskans using data from clinics participating in an accountable care organization: A study protocol. F1000Research 4: 298.

- Pitts SBJ, Lea CS, May CL, Stowe C, Hamill DJ et al. (2013) Fault-line of

an earthquake: A qualitative examination of barriers and facilitators

to colorectal cancer screening in rural, eastern North Carolina. J Rural

Health 29(1): 78-87.

- Kim J, Young L, Bekmuratova S, Schober D, Wang H et al. (2017) Promoting Colorectal Cancer Screening through a New Model of Delivering Rural Primary Care in the United States: A Qualitative Study. Rural and Remote Health.

- Wang H, Qiu F, Gregg A, Chen B, Kim J, et al. Barriers and Facilitators of Colorectal Cancer Screening for Patients of Rural Accountable Care Organizations Clinics: A Multi-Level Analysis. Journal of Rural Health.