Teres Minor: A Literature Review of its Anatomy, Function, Relations and Etiology of Disorder

Shazil Mahmood, Aaran Varatharajan*, Nabil Ebraheim and Jacob Stirton

Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of Toledo College of Medicine, USA

Submission: July 24, 2019;Published: November 13, 2019

*Corresponding author: Aaran Varatharajan, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of Toledo College of Medicine, 3000 Arlington Ave, Toledo, OH 43614, USA

How to cite this article: Shazil Mahmood, Aaran Varatharajan, Nabil Ebraheim, Jacob Stirton. Teres Minor: A Literature Review of its Anatomy, Function, Relations and Etiology of Disorder. JOJ Orthoped Ortho Surg. 2019; 2(3): 555589. DOI: 10.19080/JOJOOS.2019.02.5555589

Abstract

Purpose: This literature review is intended to provide oversight on the anatomy, incidence, etiology and presentation of teres minor dysfunction. Relevant articles were retrieved with PubMed using keywords such as “teres minor”, “rotator cuff muscles”, “teres minor atrophy”, and “teres minor anatomy”.

Methods: Literature accumulated for this study was accumulated from PubMed using sources dating back to 1985. All sources were read thoroughly, compared, and combined to form this study. Images were also added from a separate source to aid in the understanding of the teres minor. Focal points of this study included the anatomy of the teres minor, relations to the teres minor, and etiology and presentation of teres minor dysfunction.

Results: The teres minor has a multitude of functional and anatomical variations as defined by different authors presented in this study. The teres minor serves as an important anatomical landmark to the quadrangular space. However, teres minor dysfunction occurs in association with rotator cuff pathologies, in quadrilateral space syndrome, or independently. These can present as a variety of syndromes and associated pains.

Conclusions: Independent, isolated, teres minor atrophy is clinically distinct from quadrilateral space syndrome. Studies have shown no relationship between them with differences in presentation and etiology.

Keywords: Anatomy Teres minor Etiology of disorder Narrow muscle Scapula Humerus

Introduction

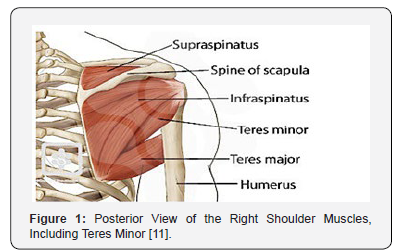

Teres minor is one of four muscles that make up the rotator cuff, along with the subscapularis, infraspinatus, and supraspinatus [1,2]. These muscles arise from the scapula and are inserted into the lesser and greater tubercles of the humerus [1,3]. Together, they are a dynamic stabilizer for the glenohumeral joint and give strength to the entire capsule of the shoulder joint except for inferiorly [1,2,4]. All relevant articles were found on the PubMed search engine, using keywords “teres minor”, “rotator cuff muscles”, “teres minor atrophy”, and “teres minor anatomy”.

Anatomy and Function

Teres minor is formed from mesoderm in the developing embryo [1]. It is a long and narrow muscle that originates from the posterior surface of the lateral border of the scapula and inserts into the humerus [1]. The mean area of insertion of the teres minor onto the greater tuberosity of the humerus is 6.2 cm25. Teres minor compromises the posterior shoulder cuff along with the infraspinatus muscle. It is innervated by the posterior branch of the axillary nerve [1,5,6]. The axillary nerve is one of the terminal branches of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, originating from the ventral rami of C5 and C6 [7]. It also supplies the deltoid muscle [7]. Vascular supply of the teres minor, as well as the rest of the rotator cuff muscles, is mainly via the suprascapular arteries and subscapular arteries [1]. The suprascapular artery arises from the thyrocervical trunk, which is a branch of the first part of the subclavian artery [8]. The subscapular artery originates most commonly off the third portion of the axillary artery and is shown to have anatomical relations with the axillary nerve and radial nerve [9]. One study found that the subscapular artery crossed with axillary nerve either anteriorly or posteriorly 69% of the time, while it crossed the radial nerve in similar orientations 82.8% of the time [10] (Figure 1).

Specific functions of the teres minor include lateral or external rotation of the arm, rotating the head of the humerus outward [1]. This results in the abduction of the arm [1]. The infraspinatus muscle has similar functions to the teres minor and is shown to have higher activity than the teres minor during flexion, abduction, and scaption of the shoulder via EMG and MRI data [6]. Both muscles also contribute to the anterior stability of the glenohumeral joint when the shoulder is abducted andexternally rotated, restricting anterior translation of the humeral head on the glenoid and thus reducing strain on anterior joint structures [2]. The strength and function of the teres minor can be tested using the hornblower’s test or sign [10]. This is conducted with the examiner initially supporting the patient’s arm at 90 degrees of abduction in the scapular plane [11]. The elbow is then flexed to 90 degrees and the patient is asked to the rotate the forearm externally against resistance [12]. If the shoulder cannot be externally rotated in this position, it shows a positive hornblowers sign and indicates teres minor dysfunction [13]. Walch found that, in a study of 54 patients, the hornblower’s sign had 100% sensitivity and 93% specificity for teres minor damage [13]. In another study, it was also concluded that maximum external rotation in abduction of the arm is a reliable method to evaluate activity in the teres minor [14].

Patients enrolled in a previous prospective randomized trial (RCT) comparing the functional outcome after stabilization of an acute syndesmosis rupture with either a 3.5mm quadricortical screw or a suture-button device were deemed eligible for this study. After IRB approval and written consent, specific assessment was achieved through a bilateral ankle computed tomography, a series of functional tests (Olerud-Molander, AOFAS) and a physical examination. Measures were compared between patients with static syndesmosis fixation or dynamic fixation. Patients were excluded if they had: a new injury to the lower limb (ipsi- or controlateral) during the interval between the end of the RCT and the control visit, pregnancy, or if they were enrolled in another center for the previous RCT (in order to standardize CT measures) or unable to comply with the study protocol (e.g. cardiac impairment, mental retardation). (Figure 1) illustrates the flow diagram of the study.

Relations of the Teres Minor

The teres minor muscle serves as an important landmark for distinct anatomical structures. One of these structures is the quadrilateral space, also known as the quadrangular space [4,7,8]. It is bound by the teres minor superiorly, the surgical neck of the humerus laterally, the long head of the triceps medially, and the upper border of the teres major inferiorly [4,8,15]. The importance of this space is that it contains the posterior circumflex artery and vein and the axillary nerve [4,7,8]. The posterior circumflex artery and vein branch off the axillary artery (third segment) and axillary vein, respectively [16]. While in the quadrilateral space, the axillary nerve splits into an anterior trunk and posterior trunk [4,7]. The anterior trunk supplies the anterior and middle muscle fibers of the deltoid, while the posterior trunk supplies the posterior muscle fibers of the deltoid and the teres minor [4,7]. There is also a cutaneous branch of the axillary nerve that comes off the posterior trunk and supplies the lateral aspect of the upper arm [4,7]. The posterior circumflex vessels similarly divide into anterior and posterior branches within the space [4]. Another important structure related to the teres minor is the triangular space. It is bound by the teres minor superiorly, the long head of the triceps laterally, and the teres major inferiorly [17]. The circumflex scapular artery, which originates from the subscapular artery, and vein traverse this space [17,18].

Etiology of the Teres Minor disorder

Dysfunction involved with the teres minor occurs in association with rotator cuff pathologies, in quadrilateral space syndrome, or independently [15]. Rotator cuff pathologies can be in the form of tendinopathy via partial or complete tendon tears [19]. These can present as an impingement syndrome with pain on overhead activity [19]. In quadrilateral space syndrome, the contents within the quadrangular space are compressed, leading to vague symptoms of shoulder pain and teres minor denervation [4,8]. Diagnosis is confirmed using MRI to observe the denervation changes on the teres minor. While the exact prevalence of quadrilateral space syndrome is unknown, reported causes of the diagnosis include glenoid labral cysts, muscle hypertrophy, and compression by fibrous bands [4]. Independent, isolated teres minor atrophy is clinically distinct from quadrilateral space syndrome and studies have shown no relationship between them [8,15]. Quadrilateral space syndrome is typically seen in younger patients, associated with paresthesia, and is positive for quadrilateral space point tenderness [15]. Teres minor atrophy is usually found in elderly patients and generally is related to pain and instability of the muscle [15]. While it is a common finding in orthopedic practice, the exact etiology of atrophy is idiopathic [8].

References

- Maruvada S, Bhimji S (2017) Anatomy, Upper Limb, Shoulder, Rotator Cuff. Stat Pearls.

- Culham E, Peat M (1993) Functional anatomy of the shoulder complex. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 74(5): 713-725.

- Dugas JR, Campbell DA, Warren RF, Robie BH, Millett PJ (2002) Anatomy and dimensions of rotator cuff insert. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 11(5): 498-503.

- McClelland DA P (2008) The anatomy of the quadrilateral space with reference to quadrilateral space syndrome. JJ Shoulder Elbow Surg 17(1): 162-164.

- Gurushantappa PK, Kuppasad S (2015) Anatomy of axillary nerve and its clinical importance: a cadaveric study. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 9(3): 13-17.

- Wilson L, Sundaram M, Piraino DW, Ilaslan H, Recht MP (2006) Isolated teres minor atrophy: manifestation of quadrilateral space syndrome or traction injury to the axillary nerve? Orthopedics 29(5).

- DeFranco MJ, Cole BJ (2009) Current perspectives on rotator cuff anatomy. Arthroscopy 25(3): 305-320.

- Naidoo N, Lazarus L, De Gama BZ, Satyapal KS (2014) The variant course of the suprascapular artery. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 73(2): 206-209.

- Jesus RC, Lopes MC, Demarchi GT, Ruiz CR, Wafae N, et al. (2008) The subscapular artery and the thoracodorsal branch: an anatomical study. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 67(1): 58-62.

- Hegedus EJ, Goode A, Campbell S (2008) Physical examination tests of the shoulder: a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. British Journal of Sports Medicine 87(7): 1446-1455.

- Walch G, Boulahia A, Calderone S, Robinson A (1998) The ‘dropping’ and ‘hornblower’s’ signs in evaluation of rotator-cuff tears. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 80(4): 624-628.

- Funk L (2017) Rotator Cuff Mechanics. Shoulderdoc.co.uk.

- Escamilla RF, Yamashiro K, Paulos L, Andrews JR (2009) Shoulder muscle activity and function in common shoulder rehabilitation exercises. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 39(8): 663-685.

- Hamada J, Nimura A, Yoshizaki K, Akita K (2017) Anatomic study and electromyographic analysis of the teres minor muscle. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 26(5): 870-877.

- Friend J, Francis S, McCulloch J, Ecker J, Breidahl W, et al. (2010) Teres minor innervation in the context of isolated muscle atrophy. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 32(3): 243-249.

- Van de Pol D, Maas M, Terpstra A (2017) Ultrasound assessment of the posterior circumflex humeral artery in elite volleyball players: Aneurysm prevalence, anatomy, branching pattern and vessel characteristics. European Journal of Radiology 27(3): 889-898.

- Wasfi FA, Ullah M (1985) Structures passing through the triangular space of the human upper limb. Acta Anatomica (Basel) 123(2): 112-113.

- Ohsaki M, Maruyama Y (1993) Anatomical investigations of the cutaneous branches of the circumflex scapular artery and their communications. British Journal of Plastic Surgery 46(2): 160-163.

- Donnelly TD, Ashwin S, Macfarlane RJ, Waseem M (2013) Clinical assessment of the shoulder. The Open Orthopaedics Journal 7: 310-315.