Abstract

Keywords: Astigmatism; Myopia; Hyperopia; Ophthalmologic; Epidemiological; Cyclopentolate; Cylindrical Ametropia

Introduction

Astigmatism, or cylindrical ametropia, is an optical defect that occurs when the cornea or the lens has an irregular shape, preventing light rays from being focused on the retina. It causes visual blur of varying intensity and affects the majority of the population. Astigmatism is commonly associated with myopia and hyperopia [1]. A global and regional systematic review and meta-analysis estimated that cylindrical ametropia is the most frequent refractive error [2]. In Côte d’Ivoire, astigmatism accounts for 64.04% of ametropias [3]. In Congo, a study of refractive errors in 432 children found that astigmatism was the most frequently observed refractive error, at 80.6% [4]. However, to date, no specific study has been conducted on cylindrical ametropias. Moreover, astigmatism occupies a major place among refractive errors and can occur at any age. We undertook this study to describe the epidemiological and clinical features of astigmatism at the University Hospital of Brazzaville.

Patients and Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in the Ophthalmology Department of the University Hospital of Brazzaville on a series of patients with ametropia from 1 January to 31 June 2025. The target population consisted of individuals with regular astigmatism. Patients aged 5 to 79 years who had undergone a complete ophthalmologic examination with objective refraction using a TOPCON AR-8900 automatic refractometer under cycloplegia with cyclopentolate were included, according to the following protocol: three instillations at 0, 5, and 10 minutes, with refraction measured between 45 and 60 minutes after the first drop. Children under 5 years of age were excluded because of the difficulty in determining refraction due to a lack of specific equipment. Patients with an organic eye disease likely to influence refraction and those who had undergone cataract surgery were also excluded. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Sampling was systematic and non-probabilistic, including all patients who met the inclusion criteria during the study period. The study variables were social (age and sex) and clinical (functional signs, visual acuity, objective refraction under cycloplegia using the autorefractometer, and type of astigmatism).

All patients with a diagnosis of ametropia after the ophthalmologic examination were referred to the investigating physician. After obtaining informed consent, the investigator reassessed the patient through an interview and clinical examination, then classified patients according to their ametropia. Astigmatism was considered from 0.50 diopters upward. For bilateral astigmatism, both eyes were included; for unilateral astigmatism, only the astigmatic eye was considered. Data were collected on standardized forms, entered using CSPro 7.4 software, and analyzed with SPSS 25 public health software. Tables and figures were generated using Microsoft Excel 2016. Statistical analysis included a descriptive phase of the study population. For quantitative variables, we calculated the mean and standard deviation. Eight age groups were considered. Frequencies of qualitative variables were compared using the chi-square test. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

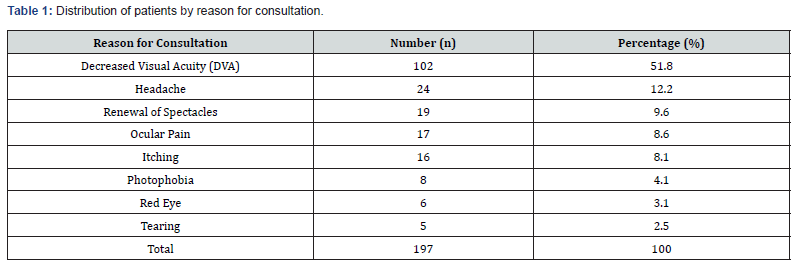

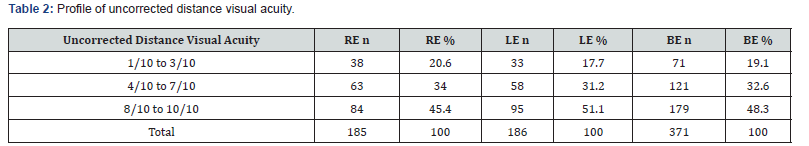

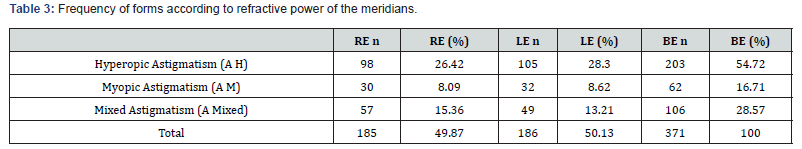

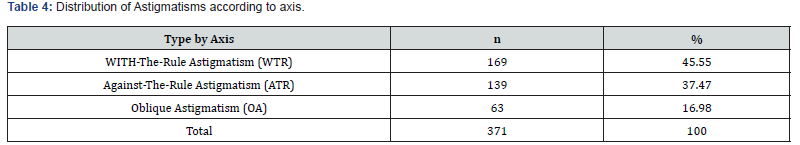

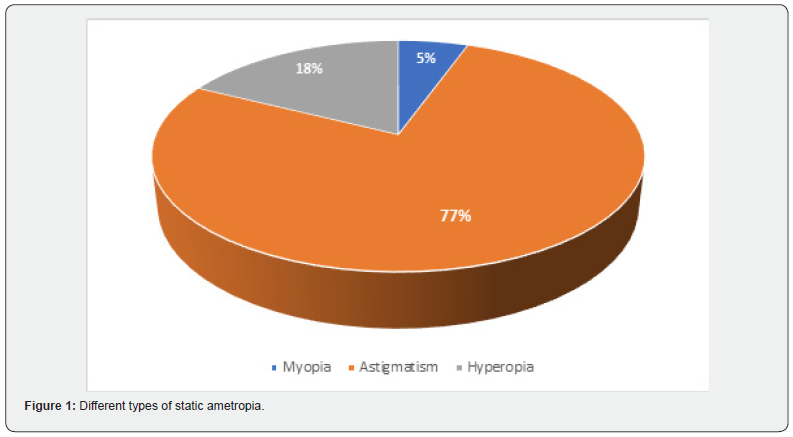

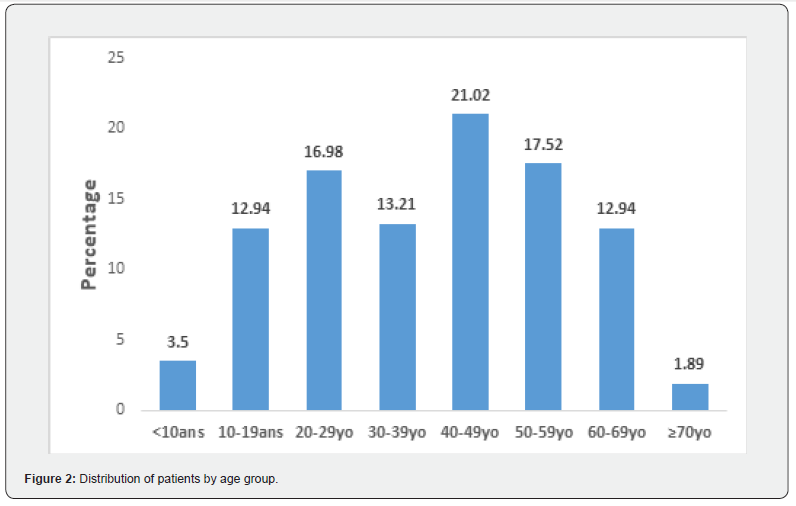

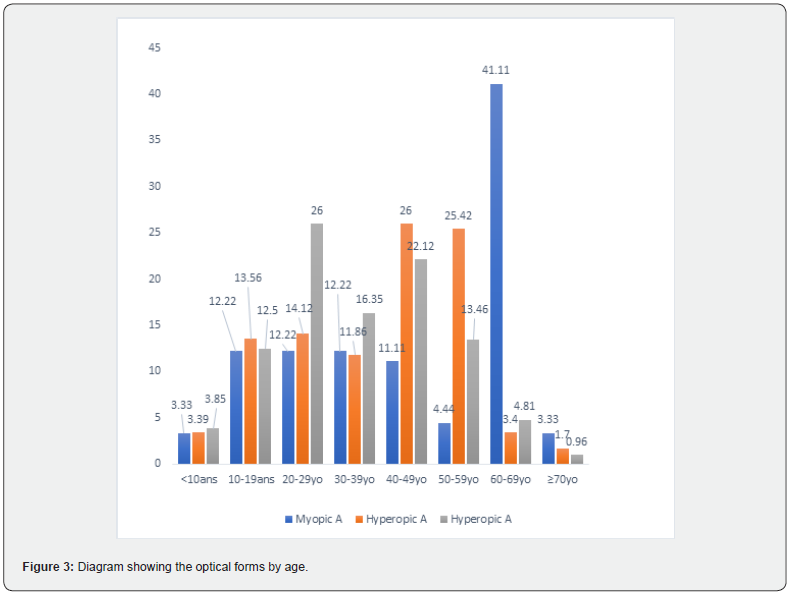

During the study period, among 256 patients with static ametropia, 197 had astigmatism, giving a frequency of 76.9% (Figure 1). Twenty-three had unilateral astigmatism (11.6%): twelve in the right eye and eleven in the left. Our sample consisted of 69 men and 128 women, for a sex ratio of 0.53. The mean age was 38.06 ± 18.2 years; the median age was 41 years, with extremes of 5 and 79 years. Astigmatism was most frequent in the 40-49-year age group (Figure 2). Among the functional signs, decreased visual acuity was present in more than half of cases (Table 1). Visual acuity ranged from 3/10 to 10/10, and the 8/10 to 10/10 range was the most frequent (Table 2). Hyperopic forms were largely predominant (Table 3), and myopic astigmatism was most common in the 60-69-year age group (Figure 3). With regard to the axis or orientation, with-the-rule (direct) astigmatism was the most frequent (Table 4).

(RE = Right Eye; LE = Left Eye; BE = Both Eyes)

(WTR = With-The-Rule; ATR = Against-The-Rule; OA = Oblique)

Discussion

Frequency of Astigmatism/

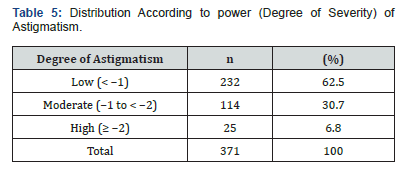

In our study, astigmatism was the most frequent ametropia, followed by hyperopia. The frequency of astigmatism can vary depending on the population studied and the diagnostic criteria used. For example, studies by Kawuma [5] in Uganda and Turaçli [6] in Turkey reported frequencies of 52% and 47%, respectively, which are lower than those reported by Makita [4] in Congo and Sounouvou [7] in Benin (80.6% and 91.9%). Methodology likely influenced these results. Kawuma [5] used a retinoscope, whereas in our previous and current studies and in the study by Sounouvou [7], an autorefractometer was used, which is highly sensitive for diagnosing astigmatism. In addition, some authors only consider astigmatism from 1 diopter, whereas we included patients from 0.5 diopters [8] (Table 5).

Social Characteristics Age

Astigmatism can affect people of all ages, children and adults. In our series, the frequency of astigmatism was low before age 10 and increased progressively up to age 49, then began to decline. A dip in the curve was observed between 30 and 39 years. This curve is similar to that reported by Leung [9] in China. However, these variations depend on the studies and sampling methods. Shih [10], who worked on schoolchildren in Taiwan, noted that the rate of myopic astigmatism increases with age, whereas the rate of hyperopic and mixed astigmatism decreases with age.

Sex

The sex ratio was 0.53, indicating a predominance of females. A similar finding was reported by Kouassi [3] in Côte d’Ivoire (sex ratio 0.76). Leung [9] in China also found a clear female predominance, with sex ratios of 0.76 and 0.75 in his series. In contrast, several studies did not find this female predominance, such as those of Chebil [11] in Tunisia and Lam [12] in Hong Kong, which reported sex ratios of 1.0. Sex therefore does not appear to influence the prevalence of astigmatism.

Clinical Characteristics Reasons for Consultation

Decreased visual acuity was the most common reason for consultation in our study, accounting for 51.8% of cases. This rate is similar to that reported by Ebana [13] in Cameroon (52%) and Maul [14] in the United States (56.3%) [15].

Uncorrected Distance Visual Acuity

More than 50% of patients had a visual acuity of less than 8/10. According to Wolffsohn [15], uncorrected astigmatism, even as low as 1.00 diopter, can lead to a significant reduction in vision and, if left uncorrected, may substantially affect patients’ independence, quality of life, and well-being.

Clinical Forms of Astigmatism

Of the three optical types of astigmatism presented in this work, hyperopic astigmatism was the most common, representing 54.72% of cases. It was followed by mixed astigmatism (28.57%) and myopic astigmatism (16.71%). These findings are comparable to those of Ayed [16] in Tunisia, who reported 57.75% hyperopic, 34.11% myopic, and 8.62% mixed astigmatism. In our study, all types of astigmatism were present at different ages, with widely varying proportions across age groups. We observed a marked increase in myopic astigmatism from age 60 onward, probably related to lens sclerosis, as demonstrated by Cho [17] in South Korea. With regard to meridian orientation, we found, in order of frequency, 45.5% with-the-rule astigmatism, 37.4% against-therule astigmatism, and 16.9% oblique astigmatism. In many studies, the frequency of these three types follows the same order and shows proportions similar to ours [11,18,19]. The predominance of with-the-rule astigmatism may explain why many patients had good visual acuity: against-the-rule astigmatism reduces distance visual acuity more than with-the-rule astigmatism [20]. In terms of astigmatic power, cylinder values ranged from-0.50 diopters to 4.25 D. Recent studies have shown that uncorrected visual acuity begins to decrease from-0.50 D of uncorrected astigmatism [21]. Mild astigmatism accounted for 62.5% of cases, moderate astigmatism for 30.7%, and high astigmatism for 6.8%. These results are comparable to those of Febbraro [22] in France and Ferrer-Blasco [23] in Spain, who reported similar rates of mild astigmatism (60% and 57%, respectively). Rabbetts [24], however, found a higher frequency of mild astigmatism (84.25%).

Conclusion

Astigmatism was the most frequently observed ametropia in this study. It affects patients of all ages, with a predominance in females. The main reason for consultation was decreased visual acuity. However, more than 48.3% of patients had visual acuity between 8/10 and 10/10. Considering meridian refractive power, hyperopic astigmatism was the most frequent type. With respect to the axis, with-the-rule astigmatism was the most common, and in terms of severity, mild astigmatism predominated. Astigmatism therefore represents a public health problem that can variably affect ocular function. Early screening and treatment are essential.

References

- Gatinel D (2006) Anomalies de réfraction: Astigmatisme. Paris Elsevier pp. 42-49.

- Hashemi H, Fotouhi A, Yekta A, Pakzad R, Ostadimoghaddam H, et al. (2017) Global and regional estimates of prevalence of refractive errors: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Curr Ophtalmol 30(1): 3-22.

- Kouassi FX (2016) Epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic aspects of childhood ametropia: About 570 cases at the University Hospital of COCODY, SOAO Review (2): 51-57.

- Makita C, Nganga NG, Koulimaya RC, Diatewa B, Massamba A, et al. (2018) Ametropia children: A review of 432 cases; Ophtalmology Research: An international journal 8(2): 1-5.

- Kawuma M, Mayeku RA (2022) Survey of the prevalence of refractive error among children in lower primary school in Kampala district. Afr Health Sci 2: 69-72.

- Turaçle ME, Aktan SG, Duruk K (1995) Ophthalmic screening of schoolchildren in Ankara Turkey. Eur J Ophthalmol 5(3): 181-186.

- Sounouvou I, Tchiabi S, Doutelien C, Sonon F, Yehouessi L, et al. (2008) Amétropie en milieu scolaire primaire à Journal Français d’ophtalmologie 31(8): 771-775.

- Atowa UC, Hansraj R, Wajuihian SO (2019) Vision problems: A review of prevalence studies on refractive errors in schoolage children. Afr Vision Eye Health 78(1): a461.

- Leung TW, Andrew KC, Li D, Chea-Su K (2012) Charactéristics of Astigmatism as a function of Age in a Hong Kong Clinical Population. Optometry and Vision Science 89(7): 984-992.

- Shih YF, Hsiao CK, Tung YL, Lin LLK, Chen CJ, et al. (2004) The prevalence of astigmatism among Taiwanese schoolchildren. Optom Vis Sci 81(2): 94-98.

- Chebil A, Jedidi L, Chaker N, Kort F, Limaiem R, et al. (2015) Characteristics of Astigmatism in a Population of Tunisian School-Children. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 22(3): 331-334.

- Lam KC, Boptom WSG (1991) Astigmatism among Chinese school children. Clinical and experimental optometry 74(9): 146-150.

- Ebana Mvogo C, Bella-Hiag AL, Ellong A, Metogo Mbarga B, Litumbe NC, et al. (2001) The static ametropia of Cameroonian black. Ophthalmologica 215(3): 212-216.

- Maul E, Barroso S, Munol SR, Speroluto KD, Ellwein LB, et al. (2000) Refractive error Study in children: Résultats from la Florida, chile. Am J Ophtalmol 129: 44-54.

- Wolffsohn JS, Bhogal G, Shah S (2011) Effect of uncorrected astigmatism on vision. J Cataract Refract Surg 37(3): 454-460.

- Ayed T, Sokkah M, Charfi OL (2002) Epidemiologic of refractive errors in schoolchildren socioeconomically deprived regions in Tunisia. J Fr. Ophthalmol 25(7): 712-717.

- Cho YK, Huang W, Nishimura E (2013) Myopic refractive shift represents dense nuclear sclerosis and thin lens in lenticular myopia. Clin Exp Optom 96(5): 479-485.

- Chen-Wei P, Barbara EK, Mary FC, Sandi S, Ronald K, et al. (2013) Racial variations in the prevalence of refractive errors in the United States: the multi-ethnic Study of atherosclerosis. Am J Ophthalmol 155(6): 1129-1138.

- Tong I, Saw SM, Carkeet A (2002) Prevalence rates and Epidemiological risk factor for astigmatism in Singapore school children. Optom vis Sci 79(9): 606-613.

- Pedro S, Catharine C, Angel ST, Michael C (2016) Distance and near visual performance in pseudophakic eyes with simulated spherical and astigmatic blur. Clin Exp Optom 99(2): 127-134.

- Villegas EA, Alcon E, Artal P (2014) Minimal amount of astigmatism that should be corrected. J Cataract Refract Surg 40(1): 13-19.

- Ferrer-Blasco T, Montés-Mico R, Pexoto-de Matos S (2009) Prevalence of corneal astigmatism before cataract surgey. J cataract Refract Surg 35(1): 70-75.

- Febbraro JL (2014) Ophthalmology in our adult patients, Distribution, evolution and visual impact. Ophthalmology Practice 8 (77): 196-197.

- Rabbetts RB (2007) Astigmatism. In: Rabbetts R.B. Clinical Visual optics. 4th Edinburgh Butterworth-Heinemann pp. 94-97.