Bardet Biedl Syndrome: About 3 Cases

Diagne Jean Pierre1*, Gueye Abou1, Aw Aissatou1, Ka Aly Mbara1, Sy El Hadji Malick1, Mbaye Soda1, Ousmane Ndiaga sengho, Marguerite Edith Quenum De Meideros1, Hawo Madina Diallo1, Joseph Matar Mass Ndiaye2 and Ndiaye Papa Amadou1

1Abass Ndao Hospital Eye Center, USA

2Ophtalmology Department of Aristide Le Dantec Hospital, USA

Submission: December 30, 2021;Published: February 03, 2022

*Corresponding author: Abass Ndao, Ophtalmology department of Aristide Le Dantec Hospital, USA

How to cite this article: Diagne Jean P, Gueye A, Aw Aissatou, Ka Aly M, Sy El Hadji M, et al. Bardet Biedl Syndrome: About 3 Cases. JOJ Ophthalmol. 2022; 9(1): 555753. DOI: 10.19080/JOJO.2022.09.555753

Abstract

Aim: To report 3 cases of Barded Biedl syndromes (BBS) with their clinical characteristics ophthalmic and therapeutic aspects.

Observations: We report 3 cases of children with a BBS. It was a descriptive and analytical study. The average age was 14 years. They were 2 boys and one girl. All the patients had an eye examination, a general pediatric examination and paraclinical exams. According to BEALES criteria, they all presented a BBS. The treatment was: diet advice; insulin therapy; corrective lenses; vitamin therapy A and E; renal protection, clinical and biological monitoring especially renal, ophthalmological and blood sugar monitoring. A child (case 3) died after 18 days in hospital of renal failure.

Discussion & Conclusion: BBS is a rare genetic disease. It is a part of a large group of syndromes called ciliopathies. The ophthalmological involvement determines the functional prognosis and the renal impairment, affects the vital prognosis. An early and correct treatment is necessary. The genetic counselling plays an important role in the prevention of this disease.

Keywords: Hemeralopia; Functional prognosis; Vital prognosis

Introduction

Bardet Biedl syndrome (SBB) is an inherited disease with autosomal recessive transmission. Currently, 22 genes (BBS1 to BBS22) have been implicated in this condition coding for proteins involved in the development and functioning of the primary eyelash [1,2]. In Africa, the first case was described in 1991 in Zimbabwe, but the genetic form was not specified [3]. The exact prevalence remains unknown on this continent. SBB is characterized by the association of major signs (obesity, retinopathy pigmentosa, polydactyly, impairment of renal function, hypogenitalism, difficulty learning) and minor (diabetes, high blood pressure, congenital heart disease, hepatic fibrosis, anosmia, dental congestion, Hirschsprung’s disease). His management remains multidisciplinary [4]. His prognosis is primarily related to renal involvement with a possible progression to end-stage renal failure and blindness generally occurring before the age of 30 years [5]. The objective of our work was to report 3 cases of SBB, recalling the clinical aspects including ophthalmology and therapy.

Observations

We report 3 cases of children with SBB. It was a descriptive and analytical study. All children had an ophthalmological examination, a general pediatric examination, and paraclinical examinations.

Case 1

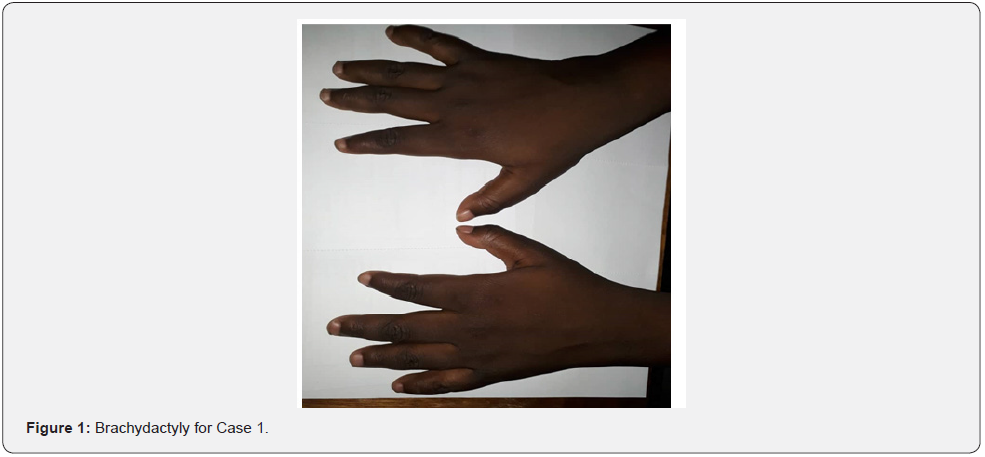

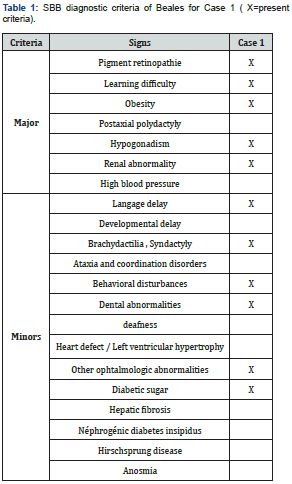

It was a boy aged 15 years, brother of case 2, seen in consultation for a decrease in vision with photophobia, excess weight, short fingers, and polyuro-polydipsia syndrome. The parents were not inbred. Visual acuity was reduced by counting fingers at 1 meter, not improving in both eyes. Automatic refraction under cycloplegia showed myopic astigmatism (right eye -8(-3.75; 110), left eye -7.5(-2.5; 85)); a horizontal pendulum nystagmus in both eyes; narrowed retinal vessels, papillary pallor, liquefied vitreous, diffuse choroїdose with rounded pigment clusters in both eyes. OCT objectified severe macular atrophy in both eyes. The body mass index (BMI) was 26.2kg/m2. Diuresis was estimated at 4 ml/kg/h. Capillary glucose was 1.45g/L, twice. The glycosuria was double cross. Examination of the other devices and systems showed: a right brachydactylia (Figure 1) and a left syndactyly; mental retardation with learning difficulties in school; behavioural disorders; and dental clutter with language impairment; a micro-penis associated with gynecomastia related to hypogonadism; facial dysmorphia (Table 1 & 2).

Fasting blood sugar was 1.41g/L with HbA1c (glycated hemoglobin) at 7%. Creatinine was 7.99mg/l with renal clearance at 83ml/min/1.73m2. The blood ionogram showed: normal natremia at 140mEq/l; normal blood potassium at 3mEq/l; normal chloremia at 100mEq/L. The abdominal-pelvic ultrasound showed poor cortical-medullary differentiation, without urinary tract abnormalities. The electrocardiogram was normal. The treatment introduced was dietary advice; insulin therapy; the use of corrective glass; vitamin therapy A and E; nephro-protection; and multidisciplinary clinical-biological surveillance including nephro-paediatric, ophthalmological and diabetological.

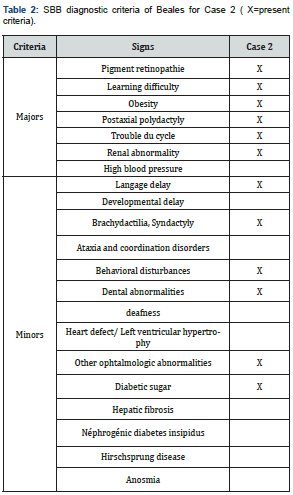

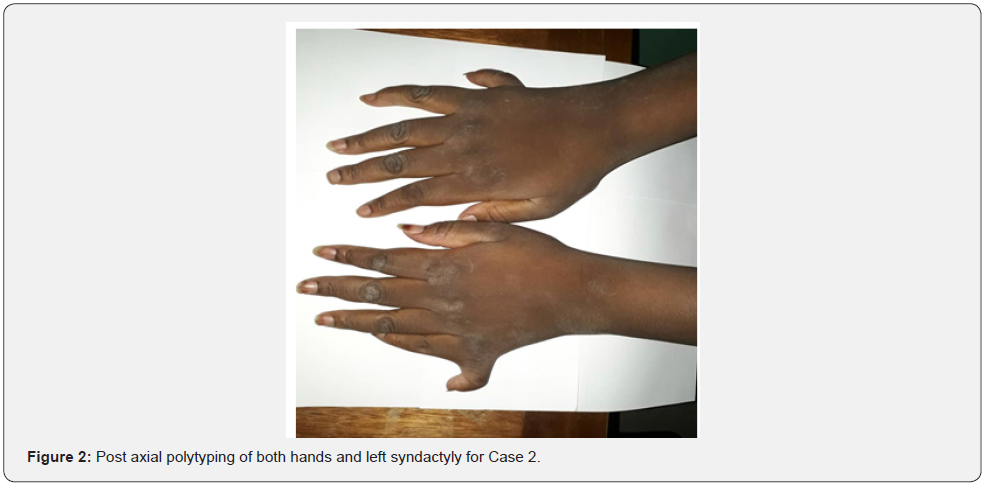

Case 2

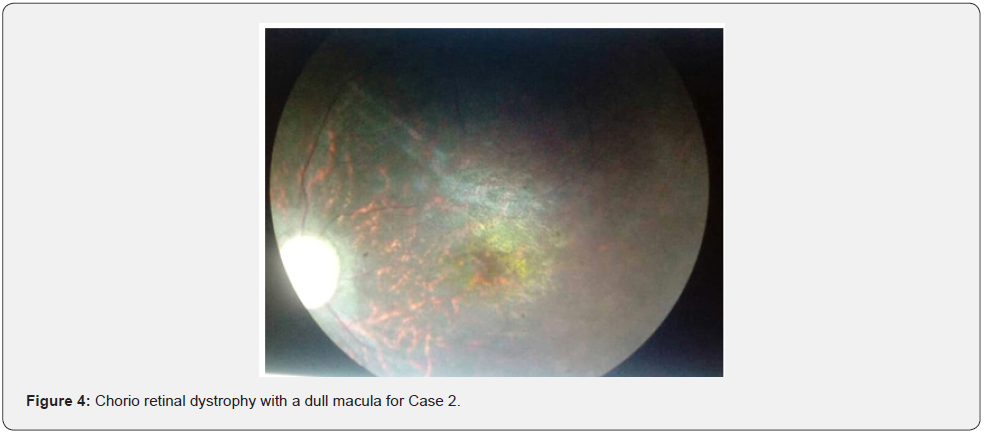

She was a 14-year-old sister of Case 1. She was seen in consultation for excess weight and a supernumerary finger, associated with decreased vision with photophobia, intellectual retardation, and polyuro-polydipsia syndrome. Visual acuity was reduced by counting fingers at 1 meter, not improving in both eyes. Automatic refraction under cycloplegia revealed myopic astigmatism under cycloplegia (right eye -6.5 (-2, 145°), left eye -6 (-1.75, 180°). We noted a permanent horizontal pendulum nystagmus in both eyes. The fundus showed a liquefied vitreous, narrowed retinal vessels, papillary paleness, rounded pigment clusters, chorio-retinal dystrophy with a dull macula (Figure 2-4). The OCT showed severe macular hypoplasia. The BMI was 31.2kg/ m2. Diuresis was estimated at 4 ml/Kg/H. Capillary glucose was 1.42g/L, twice. The glycosuria was double cross. Examination of the devices and systems showed: post-axial polytyping, brachydactylia, syntypia (Figure 2); mental retardation with learning difficulties in school; behavioural disorders; and facial dysmorphia (Figure 3); dental clutter with language impairment; moderate obesity grade II; primary amenorrhea (Table 2). Fasting blood sugar was 2.05g/L with HbA1c at 8%. Creatinine was 8.05mg/L with renal clearance at 85ml/min/1.73m2. Natremia was 135mEq/l (milliequivalent per litre). Kalemia was 3.5 mEq/L. Chloremia was 98mEq/L. An abdominal-pelvic ultrasound showed poor cortical-medullary differentiation of the kidneys, without urinary tract abnormalities. The electrocardiogram was normal. The treatment introduced was dietary advice; insulin therapy; the corrective glass port; vitamin therapy A and E; nephro-protection and multidisciplinary clinical-biological monitoring including nephro-paediatric, ophthalmological and diabetological.

Case 3

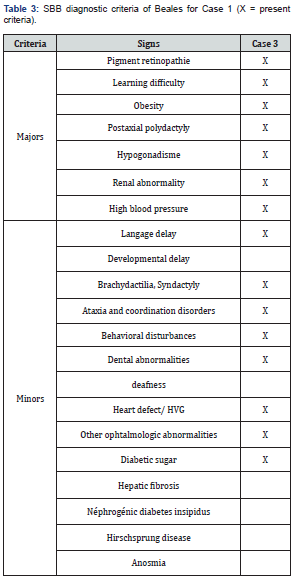

He was a 13-year-old boy referred by pediatricians for renaltype edematous syndrome. First degree parental inbreeding was noted. The BMI was 26.8kg/m2. He had oligo-anuric insufficiency. His blood pressure was 160/95 mm Hg. He had post-axial polytyping; a syndactyly; facial dysmorphia; a micro-penis; language problems with dental clutter; and behavioural disorders with coordination disorder (Table 3). Visual acuity was reduced by counting fingers in both eyes. A horizontal permanent pendulum nystagmus was noted in both eyes. He had pigment retinopathy with macular hypoplasia. Fasting blood sugar was 1.52g/L with A1c at 9%. Creatinine was 79.2mg/L with renal clearance at 6.7ml/min/1.73m2 (Figure 4). The blood ionogram showed: a kaliemia at 5.8mEq/l; a natremia at 127mEq/l and a chloraemia at 102mEq/l. The abdominal-pelvic ultrasound showed: small kidneys; a cortico-medullary dedifferentiation; an absence of urinary tract abnormalities. The electrocardiogram showed left ventricular hypertrophy with regular sinus rhythm. The treatment introduced was symptomatic measures against high blood pressure and hyperkalemia; the hydrosodium restriction; the diuretics of the loop; insulin therapy; and the hemodialysis.

The child died of kidney failure after 18 days in hospital.

Discussion

All children had more than 4 major signs according to the criteria established by Beales et al. [4] and all met the diagnosis of SBB. The prevalence of SBB in our service remains very low. We had 3 cases over a 10-year period. In Tunisia, a 21-year study (1987-2007) had collected only 11 cases [6]. The exact prevalence of SBB remains unknown in Africa [3]. The children in our study were 15, 14 and 13 years of age respectively for Case 1, Case 2 and Case 3. The age at diagnosis was late compared to the western studies [5]. In a study of visual functional exploration in SBB, two children were 4 and 6 years old and a third was diagnosed at birth [7]. A study conducted in a Congolese family found children aged 16 and 9 years at diagnosis [8]. This could be explained by a nonsystematization of the ophthalmic examination. In the Youcef et al. [9] study, 4 children were male and 2 were female. The SBB affects both boys and girls with a slight male predominance, as in our series. In the Fisli et al. [10] study, 1-degree inbreeding was observed in 4 cases. Ingster-Moati et al. [7], had found no family history or any notion of inbreeding as the example of our first two cases, which will therefore be considered sporadic cases.

Hemorrhagics, photophobia, decreased visual acuity are the most common manifestations and occur around the age of 10 [7]. This decrease in visual acuity will evolve during adolescence to reach around 20 years a visual acuity reduced to the movements of the hand or light perception [7,5]. Nystagmus is the most common manifestation of oculomotor signs. An oculomotricity abnormality exists in 64% of cases after registration of optocinetic nystagmus and oculo-vestibular reflex without any clinically suspected abnormalities [11]. A COGAN oculomotrice apraxia [12] has also been described. The strong myopia explains the severe amblyopia noted in all children, especially since they were all seen at an advanced age. The pigmentation of the middle retinal periphery appears later and is not always made up of osteoblasts, like the fundus images found in all our patients [13]. Electroretinogram is a very useful complementary examination for the diagnosis of early retinopathy but has little relevance in advanced cases where diagnosis can be easily made by fundus [14]. We have not been able to do that in our patients because of their lack of cooperation. It would have shown correlated with retinal lesions of flat plots (cone and stick damage). The signs of electroretinogram appear rather than pigment changes, hence the importance of this examination for early diagnosis [5].

High-resolution optical tomography provides detailed analysis of retinal layers in patients with SBB, with preservation of the inner and outer layers of the retina and reduced photoreceptors at the fovea [15]. Retinal dystrophy is almost constant in SBB which is considered one of the most common causes of so-called syndromic pigment retinopathy [16,17]. Given these results, pigment retinopathy could be considered as a pathognomonic sign of SBB interesting proportionately both eyes and that macular involvement is associated less consistently. This retinal dystrophy is classically described as a rod-cone type pigment retinopathy. The latter is progressive degenerative retinal damage with initial stick damage, followed by cone damage [17].

The lack of curative treatment of retinopathy pigmentosa makes the management of SBB difficult. However, its evolution must be monitored. The frequency of renal failure in the SBB varies between 42% and 100% of cases [5,18,19]. According to other authors, kidney failure is diagnosed in 30% to 60% of cases. In our study, kidney damage was present in all children; less significant in cases 1 and 2, it was much more evident in case 3 with chronic end-stage renal failure. Obesity was consistent in all children, but less significant in Case 1 and Case 3, which were overweight. It was much more pronounced in Case 2. It was truncated obesity, as found by Dollfus et al. [17]. It is most often early and appears after the first year of life [20]. It is severe from the start and worsens in the years, it causes an increased morbidity due to the associated complications and whose frequency seems increased [6]. This obesity can be disabling and is difficult to manage because of its pathogenesis. Its origin is still unclear, but a central cause would be the most likely hypothesis [21].

Diabetes mellitus, consistent in our study, was unknown before its detection and diagnosis. In the [22] study, type 2 diabetes mellitus occurred in 48% of patients and glucose tolerance impairment was Moore et al. [22] diagnosed in 4 of 46 patients. The median age of onset of diabetes mellitus was 43 years. From a therapeutic point of view, dietary measures against obesity and diabetes were introduced in all patients, as was insulin therapy in all patients. Brachydactylia was present in all our children. It was limited to the hands and spared the feet. Polytyping also only reached the hands. It was present in Case 2 and 3. It was post-axial polytyping.

In the [22] study of 36 patients, brachydactylia was present in 86% of the patients’ feet and hands. Postaxial polytyping was observed in 63% of the cases. Syndactyly and brachydactylia are considered equivalent to polydactyly [7].

Hypogonadism is present in 98% of boys and manifests as cryptorchidism, micro-penis and/or pubertal delay [4]. Girls have menstrual disorders or more rarely vaginal atresia with hydrometrocolpos at birth, or hypoplasia of the fallopian tubes [5]. In our study, genito-urinary disorders with micropenis in cases 1 and 3, hypogonadism, gynecomastia in case 1, and primary amenorrhea in case 2 were also found. The girls had no genital abnormalities. Fisli et al. [10], also had shown a cryptorchidy with a micro-penis in one out of four boys examined. The major sign of these psychiatric manifestations is the mental retardation considered as a major criterion in the SBB according to TOBIN and Beales [4]. It’s a less common sign, affecting less than 50% of patients. It is often moderate. It is to be distinguished from cognitive disorders caused by visual impairment. Many people with SBB have learning disabilities that require extra-curricular support [5]. Mental retardation was observed in all patients can be explained partly by sensory deficit, but also by neuropsychic peculiarities of patients with SBB: slow ideation and motor realization and expressive language disorders [23]. Dental congestion was present and constant in all patients and caused speech impairment secondarily. These dental conditions with small teeth, hypodontics and short roots have also been described in the literature [24].

Congenital heart defects are present in 7% of cases and include situs inversus, arterial canal persistence, cardiomyopathy, left ventricular hypertrophy or aortic stenosis [4]. Only left ventricular hypertrophy was present in case 3. In the children of our series, facial dysmorphia was manifested by a prominent forehead, bitemporal narrowing, hypertelorism, palpebral fissures oriented down and out, ptosis, sunken eyes in the orbits, enlargement of the root of the nose, antecedent nostrils and an ogival palate as reported in the literature [4,25]. On the other hand, there may be a transmission deafness or mixed deafness in 21% of cases [5], which was absent in our study.

Neurological disorders are described by some authors. They include ataxia and coordination disorders in 40% of patients with abnormal gait in 33% of patients in the Beales et al. series [25]. and 86% of patients in the Moore et al. study [22]. It may be associated with cerebellar syndrome. In our study of coordination disorders were noted only in case 3. The hypotonia of the muscles of the face is striking and gives the patients an amimic and frozen aspect that contributes to their difficulties of social integration. Based on the criteria established by Beales et al. [4], all our patients had SBB. Case 1 had 72% of major signs and 43% of minor signs. Case 2 had 86% of major signs and 43% of minor signs. And Case 3 had 100% of major signs and 57% of minor signs.

Conclusion

SBB is a rare and polymorphic genetic disorder, part of a large group of syndromes grouped under the name of ciliopathies that are characterized by primary lash injury. The functional prognosis is mainly related to ophthalmologic involvement. The prognosis was related to the existence of chronic kidney disease. However, timely and correct management of kidney disease could significantly reduce the death rate from SBB. Genetic counselling plays an important role in the prevention of this disease.

References

- Gharbi R, Bouslimi J, Ben Rhaiem B, et al. (2014) Syndrome de Bardet-Biedl : À propos d’un cas. Annales d’Endocrinologie 75(5-6): 460-464.

- Schaefer E, Stoetzel C, Scheidecker S, Geoffroy V, Prasad MK, et al. (2016) Identification of a novel mutation confirms the implication of IFT172 (BBS20) in Bardet–Biedl syndrome. Journal of Human Genetics 61(5): 447-450.

- Wolf B (1991) Bardet-Biedl syndrome in a Zimbabweanchild. Cent Afr J Med 37(10): 341-342.

- Tobin JL, Beales PL (2007) Bardet–Biedl syndrome: Beyond the cilium. Pediatric Nephrology 22(7): 926-936.

- Rooryck C, Lacombe D (2008) Le syndrome de Bardet-Biedl. Annales d’Endocrinologie 69(6): 463-471.

- Aloulou H, Cheikhrouhou H, Belguith N (2011) Le syndrome de Bardet- Biedl chez l’ Etude de 11 observations. Tunisie médicale 89(1): 31-36.

- Moati II, Rigaudiere F, Lestrade C (2000) Exploration fonctionnelle visuelle dans le syndrome de Bardet-Biedl. J Fr Ophtalmol 23: 7-10.

- Bongo CLE, Manvouri L, Monabeka HG (2014) Le syndrome de Bardet-Biedl dans une famille congolaise : À propos de 2 cas, diagnostiqués au décours d’un coma diabé Annales d’Endocrinologie75(5): 391-395.

- Youcef HS, Haddam AEM, Fedala NS (2014) Le syndrome de Bardet-Biedl: À propos de six patients. Annales d’Endocrinologie 75(5): 411-413.

- Fisli N, Khodja A, Nouri N (2017) Phénotype du syndrome de Bardet–Biedl : À propos de 7 cas. Annales d’Endocrinologie 78(4): 302-308.

- T Lavy, CM Harris, F Shawkat, D Thompson, D Taylor, et al. (1995) Electrophysiological and Eye-Movement Abnormalities in Children with the Bardet-Biedl Syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 32(6): 364-367.

- Shawkat FS, Harris CM, Taylor DSI, A Kriss (1996) The role of ERG/VEP and eye movement recordings in children with ocular motor apraxia. Eye 10(1): 53-60.

- Riise R, Andréasson S, Wright AF, Tornqvist K (1996) Ocular findings in the Laurence‐Moon‐Bardet‐Biedl syndrome. Acta ophthalmologica Scandinavica 74(6): 612-617.

- Wang DY, Chan WM, Tam POS, Baum L, Lam DSC, et al. (2005) Gene mutations in retinitis pigmentosa and their clinical implications. Clinica Chimica Acta 351(1-2): 5-16.

- Gerth C, Zawadzki RJ, Werner JS, Héon E (2008) Retinal morphology in patients with BBS1 and BBS10 related Bardet–Biedl Syndrome evaluated by Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography.Vision Research 48(3): 392-399.

- Campo RV, Aaberg TM (1982) Ocular and Systemic Manifestations of the Bardet-Biedl Syndrome. American Journal of Ophthalmology 94(6): 750-756.

- Dollfus H, Verloes A, Bonneau D, Cossée M, Schmitt FP, et al. (2005) Le point sur le syndrome de Bardet-Biedl. J Fr Ophtalmol 28(1): 106-112.

- O’Dea D, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, D Hefferton, B C Cramer, et al. (1996) The importance of renal impairment in the natural history of bardet-biedl syndrome. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 27(6): 776-783.

- Dippell J, Varlam DE (1998) Early sonographic aspects of kidney morphology in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, West) 12(7): 559-565.

- Delrue MA, Michaud JL (2004) Fat chance: Genetic syndromes with obesity. Clinical Genetics 66(2): 83-93.

- Soliman AT, Rajab A, Al Salmi I (1996) Empty sellae, impaired testosterone secretion, and defective hypothalamic-pituitary growth and gonadal axes in children with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Metabolism 45(10): 1230-1234.

- Moore SJ, Green JS, Fan Y, Bhogal AK, Dicks E, et al. (2005) Clinical and genetic epidemiology of Bardet-Biedl syndrome in Newfoundland: A 22-year prospective, population-based, cohort study. American Journal of Medical Genetics 132A(4): 352-360.

- Beales PL, Katsanis N, Lewis RA, Ansley SJ, Elcioglu N, et al. (2001) Genetic and Mutational Analyses of a Large Multiethnic Bardet-Biedl Cohort Reveal a Minor Involvement of BBS6 and Delineate the Critical Intervals of Other Loci. The American Journal of Human Genetics 68(3): 606-616.

- Borgström MK, Riise R, Tornqvist K, L Granath (1996) Anomalies in the permanent dentition and other oral findings in 29 individuals with Laurence-Moon-Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine 25(2): 86-89.

- Beales PL, Warner AM, Hitman GA, Thakker R, Flinter FA (1997) Bardet-Biedl syndrome: A molecular and phenotypic study of 18 families. Journal of Medical Genetics 34(2): 92-98.