Vitamin a Supplementation in Preschool Children. Coverage and Factors Determining Uptake in Three Districts of Ghana

Seth Lartey*, Peter Armah

Department of Eye Ear Nose and Throat, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana

Submission: September 12, 2019;Published: September 19, 2019

*Corresponding author: Seth Lartey, Department of Eye Ear Nose and Throat, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana

How to cite this article: Seth Lartey, Peter Armah. Vitamin a Supplementation in Preschool Children. Coverage and Factors Determining Uptake in Three Districts of Ghana. JOJ Ophthalmol. 2019; 8(1): 555726. DOI: 10.19080/JOJO.2019.07.555726

Abstract

The aim was to evaluate the vitamin A supplementation in three districts of Ghana. The specific objectives were to determine the proportion of children aged 6 to 59 months who received vitamin A supplements in the 12 months before 2010, to determine if the actual coverage corresponds with data from the Ministry of health of Ghana and to determine the factors associated with non-uptake of vitamin A supplements.

Methods: All the districts in the Ashanti region were stratified by ecological zone. Simple random sampling was used to select one district in each of the zones. Each selected district was divided into sub districts and probability proportional to size was then used to select villages where the clusters would be located. The caretakers of children were interviewed to get data on demographics, socioeconomics, receiving vitamin A supplements and knowledge of vitamin A. Coverage was assessed from mother’s own account and a direct inspection of the health charts of the children.

Results: Comparing mother’s account of coverage with health records showed that records of supplementation coverage were lower than coverage reported by the mothers. Seventy nine percent of mothers reported receiving one dose in the last year whilst the health charts showed 63.5%. Forty percent of the mothers reported receiving two doses in the last year against 20.1% recorded on the health charts. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, the factors associated with poor uptake of vitamin A supplements were, type of material house was made of, caretakers’ ability to correctly identify vitamin A supplements, knowledge of the medical effects of vitamin A deficiency and how the child got the vitamin A supplements.

Conclusion: This study shows satisfactory coverage if coverage is taken as receiving at least one dose in the last year but poor coverage if the recommended two doses is used. Poor knowledge of the medical effect of vitamin A deficiency and natural sources of vitamin A did not affect coverage. There is the need to improve on documentation and to redefine coverage.

Introduction

Vitamin A is an essential nutrient that is required in small amounts to maintain good health, particularly in children [1]. A recent meta-analysis of 16 published trials showed that there was a 24% reduction in risk of all mortality in children aged six months to five years in response to vitamin A supplementation. There was a 28% reduction in cause specific mortality associated with diarrhea, and a significant reduction in the incidence of diarrhea by 15% and measles by 50%. The same meta-analysis showed that vitamin A supplementation produced a 15% reduction in the incidence and prevalence of night blindness and a 68% reduction in the prevalence of blinding xerophthalmia [2]. Strategies to reduce vitamin A deficiency are promotion of home gardening, health education, food diversification and fortification, and vitamin A supplementation [3,4]. Of these strategies, distribution of vitamin A supplements is the most cost effective and has been adopted as a key component of the Millennium Development Goals of reducing under 5 mortality by two thirds by the year 2015 [5]. Vitamin A deficiency is considered a public health problem in over 60 countries including Ghana [6].

Ghana, in West Africa, has a population of approximately 25 million people, 15% of whom are pre-school age children below the age of 5 years. Although declining, the under 5 mortality rates was 112 per 1000 live births in 2010 and the infant mortality rate was 63 per 1000 live births [7]. The blindness prevalence in the whole population is estimated to be 0.9% and the prevalence of blindness in children aged 0-15years is estimated at 0.8 per 1000 [8]. In Ghana, climate and ecology influence risk factors for vitamin A deficiency disorders (VADD). Studies conducted in Ghana have shown that in the northern dry savannah areas where vitamin A rich foods cannot be grown all year round, the prevalence of night blindness is much higher than in the forest areas in the south where these foods s are abundant. In the north of the country, infrastructure and health services are also less well developed [7,9].

The policy and strategy adopted by the Ministry of Health in Ghana to combat vitamin A deficiency is to distribute vitamin A supplements to every child aged 6 to 59 months every 6 months [10]. The distribution of vitamin A is integrated into routine health services, such as immunization programs, and it is managed and supported by the Ghana Ministry of Health. In 2007, the annual health report of Ghana indicated that coverage of vitamin A supplementation was 80%. In this report, coverage was defined as the percentage of children who had received at least one dose in that year. However, because the target population of children aged 6-59 months is over 5 million this means that nearly 1 million children did not receive supplementation [11]. The aim of this study, which was conducted in central Ghana, was to validate the published coverage data and to investigate reasons why children do not receive vitamin A supplements. Information arising from the study will be of value for policy makers and planners as it will enable them to identify and target the most vulnerable groups of children.

Methods

The study was a cross sectional survey of children aged 6-59 months and their mothers and careers. It was conducted over a 5 week period in June and July of 2010 in three districts of the Ashanti region of Ghana. The estimated total population of the three districts was 600,000. A sample size of 630 was calculated assuming 20% of children would not have received vitamin A supplements in the previous year. A confidence interval of 95% was used and a design effect of 1.5. The sample was increased by 10% to allow for noncompliance. If 15% would be children aged less than 5 years a total population of 4,000 people would need to be sampled. All the districts in the Ashanti region were stratified by ecological zone: i.e. rural forest in the south, suburban/urban, and rural dry savannah in the north. Simple random sampling was used to select one district in each of the ecological zones. Each district was divided into sub-districts and probability proportional to size was then used to select the villages where the clusters would be located. In each village, the study team went to the center of the village and spun a bottle to determine which direction to start enumerating. The team then went from house to house in the chosen direction. In households with more than one child between 6-59 months, the children were assigned numbers and one adult person in the household was asked to pick one of the numbers from a ballot box. The following inclusion criteria were used: children aged between 6 to 59 months, mothers or foster mothers of eligible children were present or fathers or foster fathers of eligible children were present. Children were excluded if they were visiting from another community, had not lived in the community more than 6 months, or were seriously ill.

A pre-coded structured questionnaire was used to collect data on demographics and socio economics of participants, including educational level and the occupation of both parents and their marital status, and the proportion of income used for food, as a proxy for household economic status. In this study, coverage was defined as the percentage of children who received one dose of supplementation in the last year which was assessed in two ways. Firstly, mothers were asked if their child had received vitamin A supplements and how many over the preceding 12 months. Second, the Road to Health charts of study children were inspected for documentation of supplementation. For knowledge of vitamin A, mothers were asked to name vitamin A rich foods that knew about. They were shown vitamin A tablets amongst other capsules and asked to identify the vitamin A capsule. They were asked to state the effect on their children if they did not get vitamin A supplements. The houses of responders were then inspected to determine the materials they were made of. The distance to the nearest health center and how long it would take for the caretaker to get there was also estimated.

The study was preceded by a pilot in 3 communities not included in the study. Data were entered excel and exported into SPSS for windows for analysis. Univariate analysis was used to show the relationship between all the variables and the uptake of vitamin A. Those variables that had statistical significance in the univariate analysis were then included in a multivariate logistic regression (backward stepwise Wald) analysis with receiving supplementation as the dependent variable. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and the committee on human research publication School of Medical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Kumasi. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each household from the caretaker of the child.

Result

A total of 613 children participated in the study giving a response rate of 97%. The sample came from the following districts: Amansie east, in the forest zone, 223 children (36.4%); Eura Sekyedumasi in the savannah zone,199 children (32.5%) and Kumasi, a suburban area, 191 children (31.2%). The age and sex distribution of children is shown in Table 1. There were no gender differences overall, but older children represented only 20.7% of the sample. The majority (79.1%) of mothers reported that their child had received at least one vitamin A supplement in the preceding year: 54.9% were reported to have received one dose and 45.1 % had received two doses. 14% of caretakers were not sure if their dependents had received any supplements while only 6.9% reported that their child had not received any supplements.

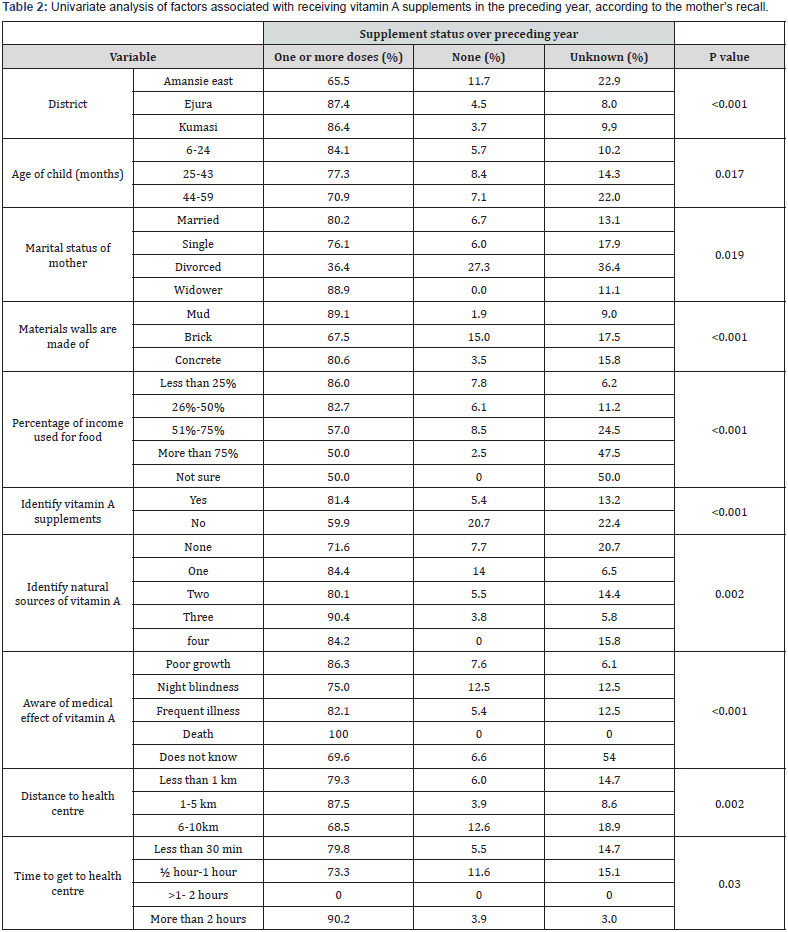

Road to Health charts were not available for review for 161 children: Supplementation status on the Road to Health charts that were available, showed that 63.5% of children were recorded as having taken a supplement: 20.1% overall (95% confidence interval [CI] 17.0-23.5%) had received two doses and 43.4% (95% CI 39.4- 47.4%) had received one. Overall 10.3% (95% CI 8.0-13.0%) of children had not received any supplements (Table 2).

There were considerable differences between the two methods of assessing coverage: 79.1% of mothers reported one or more doses compared with 63.5% documented doses. 6.9% of mothers reported that there child had had no supplements compared with 10.3% documented doses. Coverage was reportedly lower in the sample of children in Amansie east compared with the other two locations and was higher in younger than older children. Sex of the child, caretakers age, caretaker’s relation to child, education of mother and father, occupation of mother and father, material the roof of the house were not associated with supplementation status (Table 3). The only variables which remained independently associated with taking vitamin A supplements were the type of material house was made of, the caretaker’s ability to correctly identify vitamin A supplements, knowledge of the medical effects of vitamin A deficiency and where the supplements were distributed.

Discussion

The overall coverage was 79.1% (75.5, 82.2). However more than half of the children 54.9% (50.0, 59.5) had not got the full recommended supplementation of one every 6 months. In Ghana the target for 2007 was to reach 80% of children aged 6-59 months. According to official figures the target was reached and 80% of the children got at least one supplement in the year [11]. A coverage of over 79% was found in this study which corresponds to the official coverage. It also corresponds to data from neighboring West African countries, Mali and Niger who both have reported 80% coverage [12,13] but, this coverage is for those receiving at least one dose in the last one year. If we consider children who have got the full two supplementation doses in the last one year then the coverage found in the study, 54.9% is much lower.

Some of the caretakers 14% were not sure if their dependents had received any supplementation. Perhaps these mothers believing we were health inspectors would rather say they were not sure than admit their children had not got the supplements. The record of vitamin A supplementation showed that 63.5 % of the children had received at least one dose in the last one year. Out of these only 20.1% had charts showing the full recommended supplementation of 2 doses in the last year. Comparing caretaker’s account of coverage with health records showed that charts of supplementation coverage were lower than coverage reported by the mothers. One possible reason may be because of uncharted records. Because of the house to house and school distribution strategy, some of the children might not have their health charts available for documentation. Another reason may be that the mothers and caretakers in the household were over reporting coverage to please the research team. Studies in Guinea shows that the official reported coverage was higher than coverage obtained from field surveys [14].

The literature reports that factors such as mother and father’s education and living in rural areas are important determinants of coverage [12-15]. In the Philippines Choi et al reported an association between poverty and poor coverage. Children whose mothers did not complete primary education and children living in poor households were less likely to receive vitamin A supplementation [16]. We did not find a statistically significant relation with maternal or paternal education. In the multivariate analysis, the factors that came out to be predictors for poor coverage are discussed below. Caretakers’ inability to correctly identify the vitamin A supplements. It is hardly surprising that those who could identify the supplements had higher coverage, if their child had received some supplements, they were very likely to identify it especially as the supplements shown them were brightly colored. This variable may not be a good proxy for knowledge of vitamin A. If the child had got the supplements any time in the past, showing the mothers the tablet is likely to jog their memory and remind them of the supplements.

Getting the supplements at schools. Compared with school distribution, home distribution through mass campaigns was associated with better coverage. Clinic distribution was also associated with higher odds of coverage. This is hardly surprising as many poor children even if they attend school do not begin to do so until they are well over 5 years. Poor knowledge of the adverse effects of vitamin A deficiency. In Indonesia there was a positive association between caretaker’s knowledge of vitamin A and uptake of coverage [17]. In our study, poor knowledge of the medical effect of vitamin A deficiency was not associated with poor coverage. Indeed, no knowledge of the adverse effect of vitamin A deficiency was associated with better coverage. If it is assumed that the very poor who were least likely to be reached by educational programs and therefore were most likely to have no knowledge, then this finding corresponds to the finding in this study that living in mud houses (OR 2.17 95%CI 22.0,21.2) was associated with the best odds of receiving supplements. These are interesting observations. Perhaps scarce resources were being focused on and targeted at the very poorest and those considered as being not so poor may not be receiving adequate coverage. Further studies are required to explore this phenomenon and to avoid a potential reversal of the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency . There was no association between knowledge of natural sources of vitamin A and vitamin A coverage. Yet the study showed that there was poor knowledge of natural sources of vitamin A and adverse effects of vitamin A deficiency. Perhaps because the vitamin A programme in Ghana is a supplementation based and not a home gardening or an improvement of nutrition based one, education on naturally occurring vitamin A sources had not been emphasized. This is quite understandable since educational programs can be quite challenging and costly. A cost analysis of the national vitamin A supplementation programs in Nepal comparing the cost of capsule distribution with education indicates that, although the effects of both programs were similar, the capsule program achieved higher coverage rates at a lower cost while the educational intervention provided economies of scale and potential for long-term sustainability [18].

Limitations

Access to the most remote parts of the districts was not possible because of logistics and this may have introduced bias. Because of the purposive sampling of the study, the results cannot be projected to the whole country. In some district’s mothers were out harvesting beans and were not available to be interviewed so foster caretakers, usually grandmothers, who may not know everything about the child had to be interviewed. This might affect the type of response for coverage and the availability of health charts for inspection. Because of time constraints, the sample size for the study was calculated to give a precise estimate of coverage and was not calculated for risk factor analysis. For this reason, the study may not have been large enough to detect significant differences for some of the variables.

Conclusion & Recommendation

This study showed satisfactory overall coverage when at least one supplement in the year was considered. The coverage in the study was like the national statistics of 2007. However, the coverage was poor when the full recommended dosage of two supplements per year was used. There is a need for better education of caretakers on the medical effect of vitamin A deficiency especially on eye health. Could we redefine the coverage to include full coverage rather than the present at least one supplement in the last year? Admittedly this requires a major policy change. There is a need for better training of health workers on documentation of health charts.

References

- Potter AR (1997) Reducing vitamin A deficiency 314(7077): 317-318.

- Mayo-Wilson E, Imdad AH, Herzer, Fawzi WW, Chalmers TC, et al. (1993) Vitamin A supplementation for preventing mortality, illness, and blindness in children aged under 5: systemic review and meta-analysis. Vitamin A supplementation and child mortality. A meta-analysis. 269(7): 898-899.

- Traore L, Banou AA, Sacko D, Malvy D, Schemann JF (1998) Strategies to control vitamin A deficiency Santé 8(2): 158-162.

- Sommer A (1997) Vitamin A prophylaxis. Arch Dis Child 77(3): 191-194.

- Wagstaff A, Cleason M (2004) The Millennium developments goals for health: rising to the challenge. Washington DC. The world Bank.

- World Health Organization. Prevention of childhood blindness Geneva (1992).

- David P (2003) Evaluating the vitamin A supplementation programme in northern Ghana: has it contributed to improved child survival. Massachusettes

- World Health Organization (2006) Country Health systems Fact sheet Ghana. World Health Statistics.

- Micronutrient and Health (MICAH). MICAH Ghana follow-up survey report. Ghana.

- Overview of national immunization programme in Ghana Malaria vaccine decision making framework (2010).

- Ministry of Health Ghana. Independent review, Health sector programme of work. Accra (2008).

- Ayoya MA, Bendech MA, Baker SK, Ouattara F, Diane KA, et al. (2007) Determinants of high vitamin A supplementation coverage among pre-school children in Mali: The National Nutrition Weeks experience. Public Health Nutr 10(11): 1241-1246.

- Aguayo VM, Baker SK, Crespin X, Hamani H, MamadoulTaibou A (2005) Maintaining high vitamin A supplementation coverage in children: lessons from Niger. UNICEF Regional Office for West and Central Africa 26(1): 26-31.

- Bendech MA, Cusack G, Konate F, Toure A, Ba MB (2007) National vitamin A supplementation coverage survey among 6-59 months old children in Guinea (West Africa). Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 53(3): 190-196.

- Richard Semba D, Saskia Pee D, Kai S, Martin Bloem W, Raju (2008) VK Coverage of the National Vitamin A Supplementation Program in Ethiopia. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 54(2): 141-144.

- Choi Y, Bishai D, Hill K (2005) Socioeconomic differentials in supplementation of vitamin A: evidence from the Philippines. Journal of Health, Population & Nutrition. 23(2): 156-164.

- Pangaribuan R, Erhardt J, Scherbaum V, Biesalski H (2003) Vitamin A capsule distribution to control vitamin A deficiency in Indonesia: effect of supplementation in pre-school children and compliance with the programme. Public Health Nutrition 6(2): 209-216.

- Pant C, Pokharel G, Curtale F, Pokhrel R, Grosse R, et al. (1996) Impact of nutrition education and mega-dose vitamin A supplementation on the health of children in Nepal. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 74(5): 533-545.