Mood Disorder Episodes & Diagnosis in Different Settings: What Can We Learn?

Bisakha Sen1*, Justin Blackburn3, Michael A Morrisey2, Meredith Kilgore1, Nir Menachemi3, Cathy Caldwell4 and David Becker1

1 PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, Department of Health Care Organization & Policy, Ryals Public Health Building, University Blvd, USA

2 PhD, Texas A&M University School of Public Health, Department of Health Policy & Management, College Station, TX, USA

3PhD, Indiana University Fairbanks School of Public Health, Department of Health Policy & Management Health Sciences Building, Indianapolis, USA

4MPH, Alabama Department of Public Health, Bureau of Children’s Health Insurance, USA

Submission: June 16, 2018; Published: June 22, 2018

*Corresponding author: Bisakha Sen, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, Department of Health Care Organization & Policy, Ryals Public Health Building, 320, 1665 University Blvd ,Birmingham, AL, USA, Tel:205-975-8960 ; Email:bsen@uab.edu

How to cite this article: Bisakha S, Justin B, Michael A M, Meredith K, Nir M. et al. Mood Disorder Episodes & Diagnosis in Different Settings: What Can We Learn?. JOJ Nurse Health Care. 2018; 8(2): 555735. DOI: 10.19080/JOJNHC.2018.08.555735

Abstract

Objective: Over the past two decades in proportion of costs of mood disorders among children paid for by government insurance programs has increased substantially. The objective of this study is to gain a more in-depth understanding of patterns of mood disorder diagnosis (MDOD) among enrollees in the Alabama Children’s Health Insurance Program, ALL Kids.

Method: A retrospective study using claims data from ALL Kids from 2008-2014 was conducted. The proportion of ‘initial’ MDOD incidents occurring in different care settings (inpatient/ED, physician’s office, outpatient), and the predictors of these incidents, were investigated. Patterns of repeated MDOD inpatient/ED incidents were examined.

Results: Multinomial logistic regression results show black enrollees have higher relative risk ratios (RRR) of having a MDOD in inpatient/ED setting (RRR: 1.52, p< 0.01), as do Hispanics (RRR: 1.30, p< 0.01). Enrollees who receive the initial diagnosis in an inpatient/ED setting are at high risk of subsequent MDOD incidents in an inpatient setting/ED. There is no significant racial or ethnic difference in the subsequent number of inpatient/ED visits conditional on the location of the initial diagnosis.

Conclusions: The pattern of repeated MDOD incidents in inpatient/ED settings may be indicative of acuity of conditions, lack of access to alternate sources of care for mood disorders, or poor adherence to treatment and inadequate home care. Enrollees who do have such an incident may be strong candidates for case management, potentially improving enrollee outcomes as well as reducing program costs by averting avoidable inpatient/ED MDOD incidents.

Introduction

Mood disorders represent a range of mental health conditions commonly characterized by feelings of depression, exaggerated fear, and/or low self-esteem that persist or repeat over a period of months or years [1]. Examples of mood disorders diagnosed during childhood include major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and social or specific phobias [2]. Mood disorders in children and adolescents are associated with concurrent or subsequent anxiety disorders, poor coping skills, poor social skills, lower educational attainment, substance use or dependence, risk-taking behaviours, and criminal behaviour [3-6]. Prior studies on mood disorders in children indicate that, by age 18, 14.3% of adolescents will have experienced a mood disorder, that mood disorders were the second most frequent primary discharge diagnoses at age 10-14, and the leading cause of hospitalizations among children aged 1-17 [7,8]. Prior studies have also found that public sources financed more than half of all spending for mental health in the U.S, with costs for inpatient services accounting for about one fourth of total mental health expenditure. Over the past two decades, the proportion of costs of mood disorders among children paid for by government insurance programs has increased from 35.1% to 45.2%, and inpatient services account for about one-fourth of expenditures on mood disorders and other mental health conditions [9,10].

Previous work by this research team using claims data from the Alabama Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) ALL Kids, had identified mood disorders as one of the most common primary inpatient diagnoses for the most expensive 1% of enrollees. The purpose of this study is to gain a more in-depth understanding of patterns of mood disorder diagnosis (MDOD) among ALL Kids enrollees, including a more in-depth analysis of predictors of mood disorder driven hospitalizations. Specifically, we explore what proportion of ALL Kids enrollees from different demographic groups receive a ‘new’ mood disorder diagnosis each year and what proportion of MDOD occurs in an emergency room (ED) or inpatient setting, in an outpatient setting, or at a physician’s office. We are particularly interested in what enrollee characteristics are associated with the initial MDOD being in an ED/inpatient setting, and whether that initial ED/inpatient setting predicts subsequent MDOD occurrences in the same setting

Methods

We use claims data from ALL Kids from 2008-2014. At the start of our study period, ALL Kids coverage was available to Alabama residents under age 19 with family incomes between 100-200% of the federal poverty line. Beginning in October 2009, program eligibility was expanded to 300 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Enrollees faced annual premiums and copayments that vary across the income groups defined by family income and Native American status. The program is administered by the Alabama Department of Public Health, which contracts with Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama (BCBSAL) for claims processing and management, and children enrolled in ALL Kids benefit from full medical, pharmaceutical, and dental coverage from the BCBSAL preferred provider network. Enrollees pay an annual premium and experience cost sharing in the form of copayments for selected services. Children in families with incomes between 100-150% of the FPL (termed the “low-fee group”) face lower levels of cost sharing, while children in families with incomes between 150-200% of the FPL (termed the “fee group”) face higher levels of cost sharing. Children in the 200-300% of the FPL following the expansion in 2009 (termed the “expansion group”) have the same cost sharing as the fee group. The fourth group, comprised primarily of Native American children (“no fee”), is federally exempted from all cost sharing. There are no upfront annual deductibles in the ALL Kids programs, and out of pocket costs per plan year may not exceed 5% of the family income (“All Kids Children’s Health Insurance Program” 2012). Our sample includes all ALL Kids enrollees who receive a mood disorder diagnosis (MDOD) between 2008 and 2014. Data prior to 2008 are excluded from the analysis, as mental health services for ALL Kids enrollees were provided via a mental health carve-out from the initial start of the ALL Kids program until May 2008.

MDOD are identified using claims data and ICD-9 codes listed in notes below Table 1. A primary focus of our analyses is the first MDOD claim in each calendar year, and the setting in which the MDOD occurred - namely, in a physician’s office, in an outpatient setting, in the ED, or in an inpatient setting. A very small number of diagnoses happen in an unspecified setting. We further define a ‘new’ MDOD as a case where there was no diagnosis in the previous calendar year. This could be because either the enrollee was enrolled with ALL Kids in the previous year but did not have a claim for MDOD, or the enrollee was not enrolled with ALL Kids in the previous year. The later can include new enrollees or enrollees returning after a 1 year or longer break in coverage. Thereafter, we explore the extent to which the initial setting predicts;

Notes: The following ICD-9 codes are used to identify mood disorder claims:

29613 29614 29615 29616 29640 29641 29642 29643 29644 29645

29646 29650 29651 29652 29653 29654 29655 29656 29660 29661

29662 29663 29664 29665 29666 29667 29680 29681 29682 29689

29690 29699 29383 29620 29621 29622 29623 29624 29625 29626

29630 29631 29632 29633 29634 29635 29636

(a) The subsequent number of visits for a MDOD in that year, and

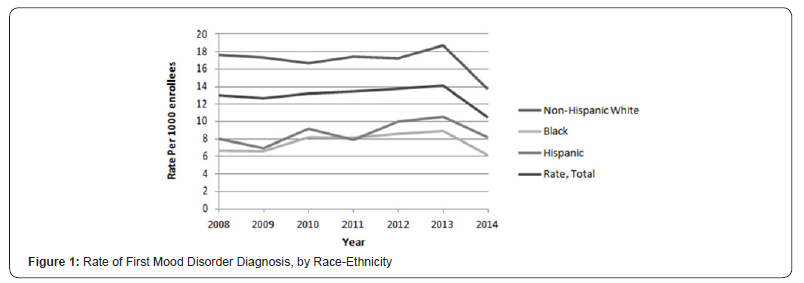

(b) The subsequent number of Inpatient/ED stays for a MDOD in that year. We present the rates of new MDOD for each year from 2008-2014, for the full sample as well as stratified by race-ethnicity in Figure 1.

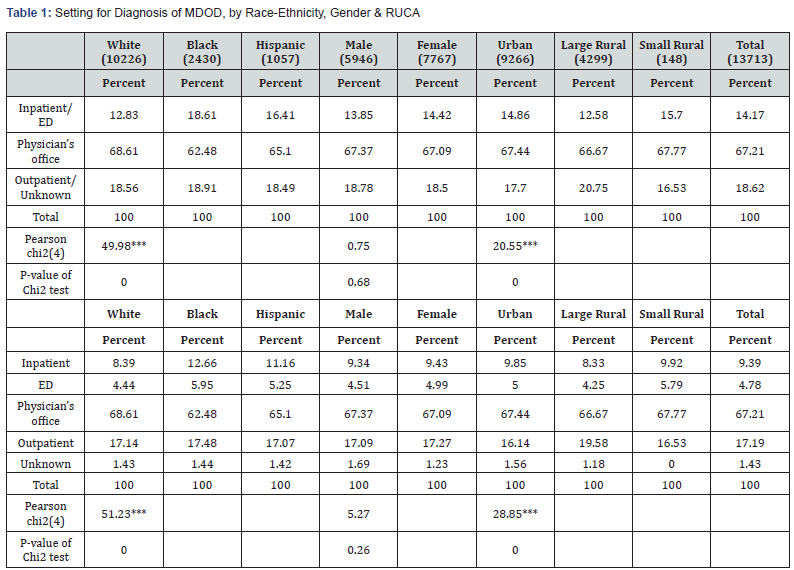

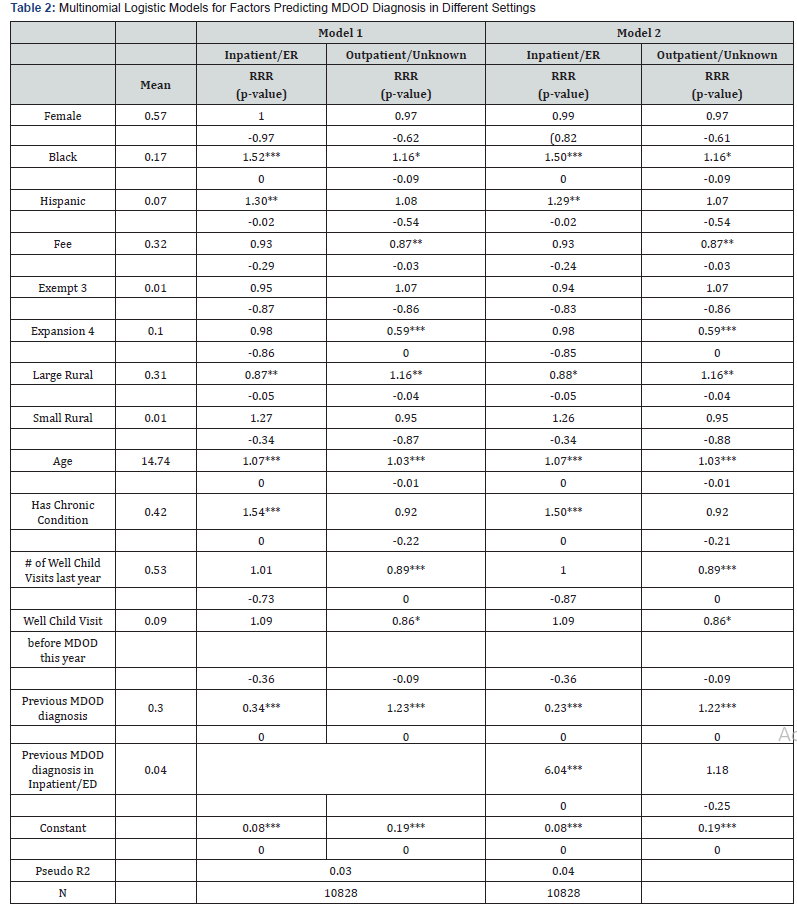

In Table 1, we present the proportion of the first MDOD in each year occurring at an inpatient/ED setting, an outpatient or unknown setting, and a physician’s office, and test whether there is a significant relationship between the diagnosis setting and race, diagnosis setting and gender, and diagnosis setting and area of residence (urban, large rural and small rural). We use multinomial logistic regressions to explore the association between several enrollee characteristics and the likelihood of the first MDOD occurring in an Inpatient/ED setting, or an outpatient setting, compared to the reference category of a physician’s office. These include socio-demographic and economic characteristics including age, gender, race-ethnicity, eligibility/FPL category, and urban/rural residency status. Since prior research suggests that MDOD is associated with chronic health conditions like asthma and other chronic medical conditions [11,12] we also include whether the enrollee has any chronic health conditions. We control for the number of well-child visits (WCV) in the previous year and any WCV in the current year, since it is possible that such visits will lead to a detection of mood disorders in settings like a physician’s office. In the second model, we also adjust for whether there had been a MDOD for that enrollee in the prior calendar year, as well as whether the previous MDOD had occurred in an inpatient/ED setting. Standard errors are clustered to account for repeated observations for the same enrollees in both models. We present results in Table 2.

*: p< 0.10; **: p< 0.05; ***: p< 0.01. The base category is MDOD diagnosis in a physician’s office.

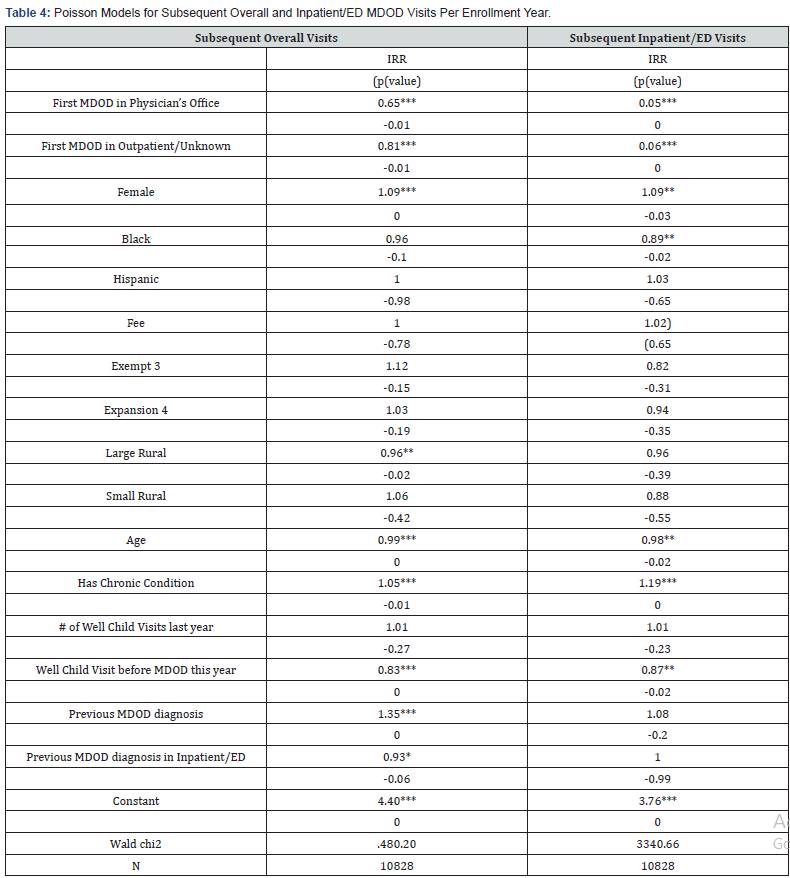

Subsequently, we estimate count data models to investigate what predicts the number of follow-up MDOD that occur in any settings, as well as the number of follow-up MDOD occurrences in an inpatient or ED setting. These models are estimated after controlling for the setting of the first MDOD in the year. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1. This study was approved by our university’s Institutional Review Board.

Results

Rates of new MDOD per 1000 enrollees show a slight upward trend from 2008 to 2013, before declining in 2014. The rates are highest for non-Hispanic whites and lowest for non-Hispanic blacks (Figure 1). Rates are significantly higher among female enrollees than male enrollees. It is seen from Table 1 that of all MDOD diagnoses, 14.7% occur in an inpatient or ED setting (9.39% in inpatient setting, 4.78% in ED setting). However, diagnosis in an inpatient/ED setting is more common for Black enrollees (18.61%) and Hispanic enrollees (16.41%) than White enrollees (12.83%). Pearson’s chi-square test finds that raceethnicity is significantly associated with the setting of the MDOD. Area of residence is also associated with setting - more small rural (15.7%) and urban residents (14.86%) have an inpatient/ED setting diagnosis than do large rural residents (12.58%). However, there does not appear to be a significant association between gender and setting of the diagnosis. Results from the multinomial logistic regression for the likelihood of an inpatient/ED diagnosis or outpatient/unknown diagnosis compared to the reference group of physician’s office diagnosis are in Table 2, which also includes means/proportions for all the model covariates. The distribution of follow up visits broken down by settings of first visit is in Table 3, and results from Poisson models are in Table 4.

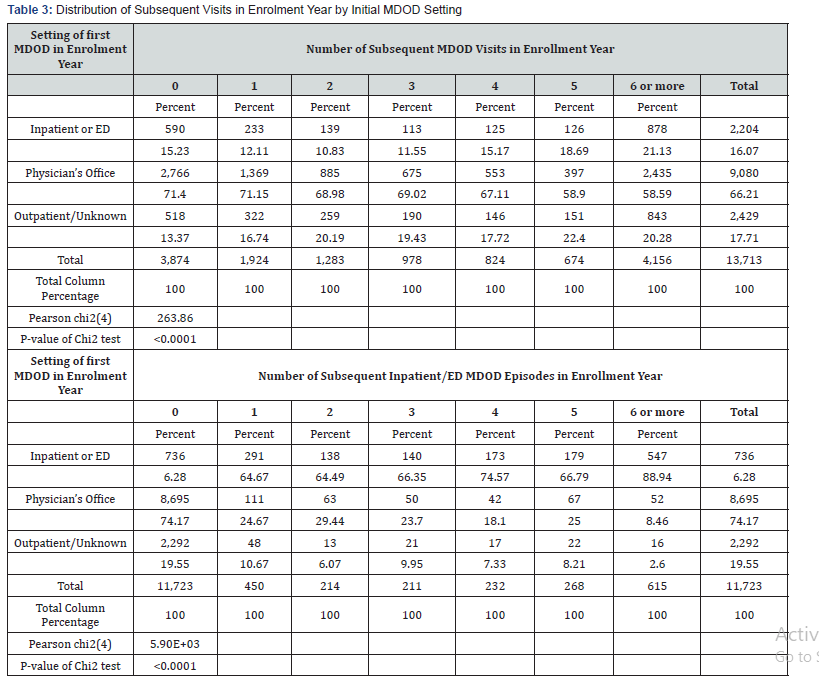

Notes: Column percentages presented in italics.

Results in Table 2 indicate that, compared to White enrollees, Black enrollees have higher relative risk ratios (RRR) of having a MDOD in Inpatient/ED setting (RRR: 1.52, p< 0.01) as do Hispanics (RRR: 1.30, p< 0.01). Residents of large rural areas are less likely to have a diagnosis in an Inpatient/ED setting than are urban residents (RRR: 0.87, p< 0.05). Age is positively associated with the likelihood of an Inpatient/ED diagnostic (RRR: 1.07, p< 0.01) as is having a chronic health condition (RRR: 1.54, p< 0.01). Well child visits, either in the previous year or in the current year prior to the MDOD, do not significantly predict the setting of the MDOD. Notably, having a MDOD per se in the previous year substantially reduces the probability of an inpatient/ED diagnosis this year (RRR: 0.34, p< 0.01). However, model 2 indicates that this is moderated by whether that previous MDOD occurred in an inpatient/ED setting - which increases the risk for an inpatient/ ED diagnosis this year (RRR: 6.05, p< 0.01). Additional analyses of frequency distributions (not shown here) confirm that, of the 4,182 enrollee observations that had a previous diagnosis, only 5.57% had a subsequent inpatient MDOD and 2.06% had a subsequent ED MDOD. However, among the subsample who had the previous diagnosis in an inpatient or ED setting, 22% had a subsequent MDOD in inpatient setting, and 5.4% had it in an ED setting.

Table 3 shows the distribution of subsequent number times a MDOD incident occurred in a year following the initial MDOD (top-coded at 6 or higher), as well as the subsequent number in an inpatient/ED setting, by the setting of the initial diagnosis. Pearson’s chi-square tests indicate that the setting of initial MDOD is significantly associated with number of subsequent visits, as well as number of subsequent inpatient/ED visits. In the case of overall visits, initial diagnosis in a physician’s office is more strongly associated with having more subsequent visits-58.6% of enrollees with six or more subsequent visits received their initial diagnosis in a physician’s office; whereas 21.13% of those with 6 or more subsequent visits received that initial diagnosis in an inpatient/ED setting. However, when considering specifically the subsequent MDOD inpatient/ED incidents, only 8.4% of those with six or more subsequent inpatient/ED received their initial diagnosis in a physician’s office, whereas 88.9% of this group received their initial diagnosis in an inpatient/ED setting.

Results in Table 4 show that, after controlling for the setting of the initial MDOD, being female is associated with more subsequent visits overall (IRR: p< 0.01) and more inpatient/ED visits (IRR: p=0.03). Area of residence has some associations with subsequent visits - those in large rural areas have significantly fewer visits than do those in urban areas (IRR: 0.96, p=0.02), but there is no significant association with number of subsequent inpatient/ ED visits. Perhaps most noticeably -- after initial MDOD setting is taken into account, non-Hispanic black enrollees have fewer subsequent inpatient/ED visits (IRR: 0.89, p=0.02). They also have fewer overall subsequent visits, though that result falls short of statistical significance (IRR: 0.96, p=0.102). Among the other control variables, age appears to have a negative association with subsequent overall and inpatient/ED MDOD visits, while chronic conditions have a positive association with both. It is also worth noting that having a well-child visit earlier that year is associated with fewer subsequent overall and inpatient/ED MDOD visits.

Discussion

Mood disorders have become the leading cause of hospital stays among children and youth in the U.S [7]. Using ALL Kids enrollment and claims data from 2008-2014, we explored the rates of ‘new’ MDOD by sub-groups, and the factors associated with MDOD occurring in an inpatient/ED setting versus physician’s office, or outpatient setting. We started by focusing on the first MDOD incident in each calendar year and predictors of the setting where it occurred. Thereafter, we considered predictors of the number of subsequent MDOD incidents, as well as the number of ED visits or inpatient episodes with MDOD, since repeated diagnosis or a physician’s office diagnosis followed by an inpatient stay is likely to reflect acuity of the condition. Our findings indicate that more than 65% of MDOD occur in physician’s offices. However, almost 10% occur in inpatient settings, and between 4.5-5% occur in ED. There are significant racial and ethnic variations in these results. Most noticeably, blacks and Hispanics are less likely to receive a MDOD diagnosis than their white counterparts. However, they are more likely to receive it in an inpatient or ED setting. We also find that children who receive an initial inpatient/ED diagnosis are much more likely to have repeated subsequent inpatient/ ED visits with MDOD, and constitute of more than 88% of all those who have 6 or more subsequent inpatient/ED visits. Also, noticeably, conditional on where the initial diagnosis occurs, there is little evidence to suggest that racial and ethnic minorities have a higher risk of subsequent inpatient/ED visit than their white counterparts. Therefore, the issue is likely to be where the initial diagnosis occurs, with the possibility that children regardless of race or ethnicity may be falling into a ‘pattern’ of recurring inpatient/ED MDOD episodes.

There exists a significant literature on disparities in paediatric mental health, including disparities in diagnostic assessment, differences in caregiver perceptions for the need for seeking health services, and constraints on access see Alegria et al, for a review [13]. There is evidence that teachers and other adults are equally likely to encourage parents of non-minority and minority children to seek medical help when the child has symptoms of ‘externalizing disorders’ like attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but less likely to encourage non-Hispanic black parents compared to white parents to seek help in case of ‘internalizing disorders’ such as depression [14]. Furthermore, for children with internalizing disorders, black parents were significantly less likely than white parents to seek help, unless they were encouraged to do so by other adults [14]. The combination of lower rates of overall MDOD diagnosis but higher likelihood of initial diagnosis in an ED/Inpatient setting suggests that ALL Kids minority enrollees are more likely to receive a MDOD only when the situation is serious enough or has been exacerbated enough to warrant hospitalization. Another challenging finding is the somewhat mixed results regarding the association between well-child visits and initial MDOD setting - specifically that wellchild visits do not appear to be associated with reduced likelihood of MDOD in an inpatient/ED setting compared to a physician’s office. This supports what previous literature has indicated - that primary care physicians may fail to recognize depression and other internalizing mental health problems, and may be more prone to focus on diagnosis and treatment of the external physical symptoms like weight fluctuations, headache, gastro-intestinal disorders or sleep problems [15]. However, well-child visits may have some benefits as well in this context, since results indicate that well-child visits are associated with fewer subsequent MDOD occurrences after explicitly controlling for setting of the initial MDOD.

While it may be difficult for a program like ALL Kids to a priori identify children at the highest risk an initial MDOD diagnosis in a inpatient/ED setting, the pattern of repeated visits suggest that enrollees who have their first MDOD incident in an inpatient/ ED setting may be considered for care management by ALL Kids. Extant literature finds a high rate of hospital readmission among adult patients with mood disorders [16]. One concern has been failure of treatment adherence subsequent to discharge, partly since mood disorder patients had a very high likelihood of being discharged to home care, often with inadequate support or instructions [16]. Very little is known about treatment adherence or support for home care for child patients with MDOD - indeed one literature review published in 2005 found no studies focusing exclusively on treatment adherence among children or adolescents with mood disorders despite the well-published prevalence rates [17]. Thus, while the repeat visits may be indicative of severe acuity of condition, they may also be driven by poor treatment adherence or lack of home care, and there is potential for care management to be beneficial both for enrollee outcomes and for program costs.

We acknowledge several shortcomings of this study. One limitation is that a high proportion of children do not stay continuously enrolled in ALL Kids, and we lack information of

their mood disorder or other mental health diagnosis, or their health service use in the periods when they are not enrolled. Additionally, we have no method for assessing the acuity of the condition, and cannot decipher whether the pattern of recurring MDOD in an inpatient/ED setting is an indicator of severity of the condition, lack of access to physician’s office or outpatient resources, or poor treatment adherence. Finally, we cannot assess whether MDOD in one setting versus another is associated with the enrollee’s quality of life, educational attainment, or familial and social interactions, or engagement in risk-taking behaviors. In conclusion, our results indicate that physicians as well as caregivers need to be more cognizant of the possible underdiagnosis of mood disorders among minorities at less acute stages. Our results also indicate that those with an initial inpatient/ ED MDOD are extremely likely to have repeated inpatient/ED episodes for MDOD, and pubic insurance programs may consider such enrollees as strong candidates for care management. Finally, we emphasize that any attempts to reduce MDOD in inpatient/ED settings must be tempered by considerations of acuity of condition as well as quality of life and long run health outcomes of enrollees.

References

- (1999) US Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration & Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, and National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health.

- (1994) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (4th edn), American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, USA.

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR (1998) Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev 18(7): 765-794.

- Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB (1995) Social-consequences of psychiatric-disorders. 1. educational-attainment. Am J Psychiatry 152(7): 1026-1032.

- Copeland WE, Miller Johnson S, Keeler G (2007) Childhood psychiatric disorders and young adult crime: a prospective, population-based study. Am J Psychiatry 164: 1668-16675.

- Crum RM, Green KM, Storr CL (2008) Depressed mood in childhood and subsequent alcohol use through adolescence and young adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65(6): 702-712.

- Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Stocks C (2015) Most frequent conditions in U.S. hospitals, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief, p. 1-12.

- Huffman LC, Wang NE, Saynina O (2012) Predictors of hospitalization after an emergency department visit for California youths with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Serv 63(9): 896-905.

- Mark L, Levit K, Coffey R (2007) National Expenditures for Metal Health Services and Substace Abuse Treatment, 1993-2003. Book National Expenditures for Metal Health Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

- Lasky T, Krieger A, Elixhauser A (2011) Children’s hospitalizations with a mood disorder diagnosis in general hospitals in the united states 2000-2006. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 7(5): 27.

- Delmas MC, Guignon N, Chee CC (2011) Asthma and major depressive episode in adolescents in France. J Asthma 48(6): 640-646.

- Reilly C, Agnew R, Neville BG (2011) Depression and anxiety in childhood epilepsy: a review. Seizure 20(8): 589-597.

- Alegria M, Vallas M, Pumariega A (2010) Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Pediatric Mental Health. Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America 19(4): 759-774.

- Alegría M, Lin JY, Green JG (2012) Role of Referrals in Mental Health Service Disparities for Racial and Ethnic Minority Youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 51(7): 703-711.

- Eisenberg L (1992) Treating depression and anxiety in primary care. New Eng J Med 326:1080-1084

- Heslin KC, Weiss AJ (2015) Hospital Readmissions Involving Psychiatric Disorders, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #189.

- Gearing RE, Mian IA (2005) An Approach to Maximizing Treatment Adherence of Children and Adolescents with Psychotic Disorders and Major Mood Disorders. The Canadian Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Review 14(4): 106-113.