How are our Patients Equipped to Cope at Home after HPN Training?

Mette Holst1*, Helle Kjeldbjerg Bendtsen1, Henrik Hojgaard Rasmussen1,2 and Lars Vinter-Jensen4

1 Department of Gastroenterology, Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark

2 Department of Clinical Medicine, The Faculty of Medicine, Aalborg University, Denmark

Submission: May 20, 2018; Published: June 07, 2018

*Corresponding author: Mette Holst, Head of Clinical Nutrition research, RN, MCN, PhD, Department of Gastroenterology, Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark, Tel:+4527113236; Email: vijay.sndcon@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Holst M, Bendtsen HK, Rasmussen HH, Vinter-Jensen L. How are our Patients Equipped to Cope at Home after HPN Training?. 2018; 8(2): 555731. DOI: 10.19080/JOJNHC.2017.08.555731

Abstract

Background: During the past decades, the population of patients suffering from chronic intestinal failure has increased exponentially. HPN is life-sustaining, however associated with decreased physical, social and psychological health and self-dependence.

Rationale: The study aimed to evaluate whether training and education of patients was sufficient in order for patients to cope with HPN management and their new life conditions, and to achieve a qualified idea of how to improve the training, education and follow-up strategy.

Method: Registration of all unplanned phone-calls and visits over a 3-month period was done for patients who were discharged with HPN within the past year, and their home-care nurses, when these were involved. Problems related to catheter care and HPN, stoma care, medication, and others were recorded. At the end of the conversation, patients were asked how they otherwise felt and were able to cope with conditions. Descriptive analysis were made.

Results: Of the 45 patients discharged within the year, 42 had 102 unplanned contacts. Five queries related to acute fever, and six to redness at the injection site, while 14 inquiries concerned weight loss or fluid status. The most common reason for contact was related to catheter problems. No difference between the frequency of inquiries from home care nurses or patients themselves regarding catheter problems (NS). Medication and stoma problems were also frequent concerns. In more than half of all inquiries, there were several issues that the patients wanted to talk about. The need for personal support and the feeling of having nobody to share with, was the predominant finding in the open ended question. These issues impair quality of life.

Conclusion: Overall patients were well-equipped to know when they had reason for insecurity. Thereby, education regarding observations of catheter site and fever, dehydration and monitoring weight as well as stoma care is found sufficient for patients to cope. A need for optimizing medicine charts is required, as well as support between patients.

Keywords: Home Parenteral Nutrition; intestinal failure; Patient care; Coping; Patient education; Qualitative study

Introduction

Home parenteral nutrition (HPN) is the life-sustaining therapy in chronic intestinal failure (CIF), for patients who are unable to maintain nutrient and fluid balance by metabolic adaptation and oral compensation, also known as severe Type III intestinal failure. The condition requires intravenous supplementation over months to years, while more than 50% of the patients are confined to HPN via a central catheter for the remains of their lives, depending of the etiology of the primary disease [1,2]. Although the therapy is life-sustaining, HPN is associated with decreased physical health due to recurrent events from underlying disease, risk of catheter related complications including primarily central line related infections and venous thrombosis, parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease, and metabolic bone disease [1-5]. Furthermore, patients with CIF suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhoea or large stomal outputs, fear of incontinence and abdominal pain [2,6]. Socially and psychologically many HPN- patients live a life with fatigue, increased occurrence of depression and social isolation, contributing to a lower quality of life [6-11].

During the past decades, the population of patients suffering from chronic intestinal failure has increased exponentially [12]. This is also the case in our population of HPN patients at Aalborg University Hospital, Center from Nutrition and Bowel Disease (CET) where currently 175 patients are followed by the multi professional team in the outpatient clinic, and 12 hospital beds are allocated to intestinal failure type II and III, and to other specific malnutrition conditions.

The Setting

When patients are referred to CET, they most often have a very long history of hospitalization and severe conditions behind them. Many patients have felt life threatened due to their underlying disease, and due to disease related malnutrition [13]. Furthermore, post-traumatic stress disorder, particularly when there have been post-operative complications, occurs frequently [1]. At CET, the patients are mainly at stage Type II, and need first of all to be treated by the SNAP and SOWATS model [1]. Secondly, an assessment of nutritional status and absorption is thoroughly evaluated, in order to initiate the longer-term treatment. At this stage, approximately half of the patients are generally feeling somewhat better, and are able to begin to cope with the training towards self-management of home parenteral nutrition. Patients who are not ready or able to cope with training at this time, are discharged with the home-care nurse management of HPN including catheter care. These patients are evaluated at a later time, most often three to six months, with regard to whether they feel confident to receive training aimed at taking over some of or all the HPN-care themselves. Regardless of who takes care of HPN and catheter care, patients will be followed closely by one of two specialist consultants and a Specialist nurse in the outpatient clinic, with increasing time interval. Besides these, the multiprofessional team consists of a dietitian, a pharmacist, a bio medical laboratory scientist, and a psychologist. All HPN patients have open access for contacting CET by telephone, visit or admission to the unit. During the daytime and evening, all phone calls are serviced by a specialized HPN nurse.

Training of the Patients towards HPN-Self Care

Training and education of the patients aims at preventing catheter related infections, and other adverse events i.e. dehydration, and at teaching the patients strategies to cope with the very changed life at home. The training is individual and includes practical handling of catheters, sterile techniques, shift of catheter dressings, as well as opening, mounting and dismantling the parenteral nutrition, and closing and flushing catheters. Furthermore, information and tests are given in the safe handling, time to infusion and durability of IV-products. The training in handling the catheters takes a minimum of three days, where the patients are hospitalized. Relatives are encouraged to participate in the training and given the possibility to stay for a couple of days if necessary. The education and training is done as peer-to-peer training at the bedside and in an office in the ward.

In CET the nurses found that there were many telephone calls and unplanned visits from patients in the first year after discharge with HPN. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether training and education of patients was sufficient in order for patients to cope with HPN management and their new life conditions, and to achieve a qualified idea of how to improve the training, education and follow-up strategy. At the time of the study, 139 patients were registered as HPN-patients allocated to the team. Of these, 45 patients were newcomers discharged with HPN within the year.

Methods

A registration of all telephone inquiries to CET nurses during the day and evening shifts, as well as unplanned visits over a 3-month period was done for patients who were discharged with HPN within the past year, and their home-care nurses, when these were involved. Problems related to catheter care and HPN, stoma care, medication, and others were recorded, including which profession needed to be involved in solving the problem underlying the contact. Descriptive analysis was made. At the end of the conversation, patients were asked how they otherwise felt and were able to cope with conditions. This was set as an open ended question, and the nurses wrote down their overall impression of what was most meaningful for the patient to tell and talk about.

Ethical Considerations

When the patients were discharged from hospital, they were given information about the study. When patients took contact to the nurses at CET, they all gave consent to participate. The study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration of 2002. The study was put forward to the local ethic committee, which had no objections due to the quality improvement strategy and no involving of biological material.

Results

General

During the three month period 102 inquiries from 42 out of the 45 patients, mean age 65 (range 25-87) were registered. Of these, 44 were telephone calls from home care nurses, but all patients wanted to talk to the HPN-nurse themselves anyways when encouraged. Five queries were related to acute fever, and six to redness at the injection site. Of the total, 14 inquiries concerned weight loss or fluid status. In more than half of all inquiries there were several issues the patient wanted to talk about.

Catheter-Related Contacts

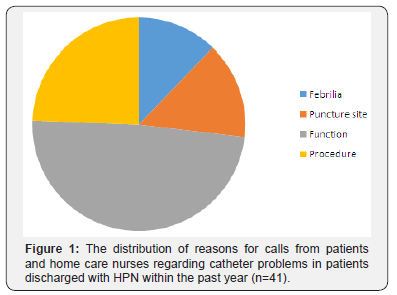

The most common reason for contact was related to catheter problems. Figure 1 shows reasons for contacts related to catheter problems. Of those, catheter dysfunction (return, inlet, defective) was the most common (n = 20). No difference between the frequency of inquiries from home care nurses or patients themselves regarding catheter problems (NS) was found. Fever and puncture site problems were evaluated by the nurse in charge as acute problems, while the more experienced and well educated patients may have been able to cope with some of the remaining problems.

Therapy-Related Contacts

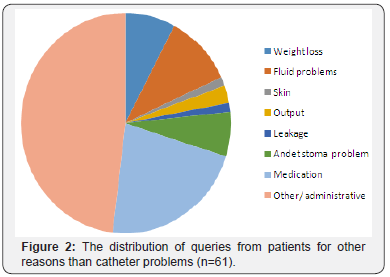

The second most common cause was related to medication (n=17) including questions about delivery, dosage and modes of administration. Inquiries concerning weight loss or fluid status were not considered as being due to lack of training, education and experience, since it is common that requirements develop over time, and these all need medical attention, as also the case for some dosage of medicine problems. The nine queries concerning stoma problems were neither considered lack of training, since these all required stoma nurse specialist experience.

Other Reasons for Contacts

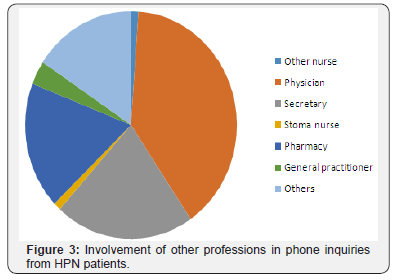

Secondary reasons for contact, when patients had more issues to talk about, 37 queries were administrative regarding blood sample testing, and ambiguity of outpatient visits. Figure 2 shows non-catheter related reasons. In 34% of cases, the HPNnurse solved the problem solely, but many other professions were involved, and in many cases more than one part. Figure 3 shows other professions involved in solving the problems.

How are you - and how do you Cope with Conditions Nowadays?

In the vast amount of contacts, the HPN-nurses found that this question “fell in a dry place”, as patients were very talkative. Coming back to daily life was obviously not always easy. Most patients expressed feeling exhausted and spending much time resting or sleeping, when they were home alone and not handling HPN care or stoma. Exhaustion was expressed at related to poor night sleep due to nocturia, a mess of infusion lines and cords, and to worries about future life. Nurses found that many patients had a need to talk over and over again about their medical course and what brought them where they are today. One patient told about how he woke up days after surgery with a totally changed life “Saturday morning, I wake up in bed, with stoma and parenteral nutrition. So that’s my new life. It was Satan’s proper birth”. Keeping the mood up was found quite difficult to some. As one of the patients (female 54 years) expressed “Sometimes I have days when I think” is it worth it- it’s not”... but I have two children, so… but I’m not sure I was here if I did not have them”. Many of the patients expressed how they would try to “Shape up” in front of their family and relatives, because they felt ashamed of the burden they also put onto their lives. The feeling of being alone with the problems is however strengthened by trying to put a positive smile up in front of the family. Patients appreciate the help and support they receive from the department, but most of them felt a need to talk to somebody who shared their own situation, as they had benefited from during hospital stay. A few still had contact with other patients, and found the connection very encouraging. With regard to the quality and extent of training and education, none of the patients mentioned this in the open interview.

Discussion

This study sought to investigate how our HPN-patients were equipped to cope at home after HPN training in hospital, within the first year after training. Of the 45 patients discharged within the year, 42 took unplanned contact during the three months investigation. Contacts were primarily by phone, however some patients also showed up at the department. Even though some patients made their home care nurse do the call, all patients were more than willing to talk to the HPN-nurse themselves anyways on the same occasion. Of the 102 unplanned queries, 30 were due to fever, injection site or weight loss or fluid status. While competency and experience in caring for the catheter is closely related to fever and puncture site, this study does not qualify to answer whether lack of training was to blame for these events [1,14-16]. Overall the causes for all unplanned contacts gave reason to believe that patients were well-equipped to know when they had reason for insecurity, and that they felt secure to call the HPN-nurses whenever they felt unsafe. Also the contacts regarding stoma problems, were considered specialist tasks, and thus well-known complex issues that they could not have been equipped for by improved training [9,14]. Thereby, education regarding observations of catheter site and fever, dehydration and monitoring weight as well as stoma care is found sufficient. In 17 (22%) of contacts patients felt uncertainty about dosing and administration regarding medicine. Most of these patients receive very high amounts of medication in different administration forms and dosages that change frequently, however no studies or guidelines have been found that give advice to how to teach patients how to manage this, or strategies to keep track. This is an area for further investigation and development. Another aspect is the need for personal support and the feeling of having nobody to share these issues of life with. These issues impair quality of life, which has been seen in many other studies beforehand [7].

Perspective

In our department, we will now consider inviting patients into groups that can meet, with the help from experienced HPNpatients. Furthermore, we will look into strategies for an improved medicine chart, which may be differed between age groups, since most but not all of our patients are very IT-capable.

Conclusion

This study aimed to investigate how our HPN-patients were equipped to cope at home after HPN training in hospital, within the first year after training. Of the 45 patients discharged within the year, 42 took unplanned contact during the three months investigation. Overall the causes for all unplanned contacts gave reason to believe that patients were well-equipped to know when they had reason for insecurity. Thereby, education regarding observations of catheter site and fever, dehydration and monitoring weight as well as stoma care is found sufficient. A need for optimizing medicine charts is required, as well as a basis for social support between patients.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated with their experiences, and the HPN nurses for a high but important work-load during the study. Mette Holst wrote the paper, which was read through by co-authors.

References

- Klek S, Forbes A, Gabe S, Holst M, Wanten G, et al. (2016) Management of acute intestinal failure: A position paper from the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) Special Interest Group. Clin Nutr 35: 1209-1218.

- Pironi L, Arends J, Baxter J, Bozzetti F, Pelaez RB, et al. (2015) ESPEN endorsed recommendations: Definition and classification of intestinal failure in adults. Clin Nutr 4: 171-180.

- Christensen LD, Holst M, Bech LF, Drustrup L, Nygaard L, et al. (2016) Comparison of complications associated with peripherally inserted central catheters and Hickman TM catheters in patients with intestinal failure receiving home parenteral nutrition. Six-year follow up study. Clin Nutr 35: 912-917.

- Bech LF, Drustrup L, Nygaard L, Skallerup A, Christensen LD, et al. (2016) Environmental Risk Factors for Developing Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection in Home Parenteral Nutrition Patients: A 6-Year Follow-up Study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 40: 989-994.

- Skallerup A, Nygaard L, Olesen SS, Kohler M, Vinter Jensen L, et al. (2017) The prevalence of sarcopenia is markedly increased in patients with intestinal failure and associates with several risk factors. Clin Nutr.

- Winkler MF, Smith CE (2014) Clinical, Social, and Economic Impacts of Home Parenteral Nutrition Dependence in Short Bowel Syndrome. J Parenter Enter Nutr 38: 32S-37S.

- Holst M, Ryttergaard L, Frandsen LS, Vinter Jensen L, Rasmussen HH (2018) Quality of Life in HPN Patients Measured By EQ5D-3L including VAS. Journal of Clinical 2(1): 1-5.

- Carlsson E, Persson E (2015) Living with intestinal failure caused by Crohn disease: not letting the disease conquer life. Gastroenterol Nurs 38: 12-20.

- Kalaitzakis E, Carlsson E, Josefsson A, Bosaeus I (2008) Quality of life in short-bowel syndrome: Impact of fatigue and gastrointestinal symptoms. Scand J Gastroenterol 43: 1057-1065.

- Berghoefer P, Fragkos KC, Baxter JP, Forbes A, Joly F, et al. (2013) Development and validation of the disease-specific Short Bowel Syndrome-Quality of Life (SBS-QoL???) scale. Clin Nutr 32: 789-796.

- Huisman-De Waal G, Bazelmans E, Van Achterberg T, Jansen J, Sauerwein H, et al. (2011) Predicting fatigue in patients using home parenteral nutrition: A longitudinal study. Int J Behav Med 18: 268- 276.

- Brandt CF, Hvistendahl M, Naimi RM, Tribler S, Staun M, et al. (2017) Home Parenteral Nutrition in Adult Patients With Chronic Intestinal Failure: The Evolution Over 4 Decades in a Tertiary Referral Center. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 41: 1178-1187.

- Holst M, Rasmussen HH, Laursen BS (2011) Can the patient perspective contribute to quality of nutritional care?. Scand J Caring Sci 25(1): 176- 184.

- Aeberhard C, Leuenberger M, Joray M, Ballmer PE, Muhlebach S, et al. (2015) Management of Home Parenteral Nutrition: A Prospective Multicenter Observational Study. Ann Nutr Metab 67: 210-217.

- Dreesen M, Pironi L, Wanten G, Szczepanek K, Foulon V, et al. (2015) Outcome Indicators for Home Parenteral Nutrition Care: Point of View From Adult Patients With Benign Disease. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 39: 828-836.

- Dreesen M, Foulon V, Vanhaecht K, Hiele M, De Pourcq L, et al. (2013) Development of quality of care interventions for adult patients on home parenteral nutrition (HPN) with a benign underlying disease using a two-round Delphi approach. Clin Nutr 32: 59-64.