- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Assessing the Tribal Public Health Workforce Needs in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho: Results from the Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council Epidemiology Center

Allyson Kelley Dr PH MPH CHES1, Mike Andreini MPH2* and Dyani Bingham BA3

1Senior Scientist, Allyson Kelley & Associates PLLC, Sandia Park NM 87047, USA

2Director, Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council Epidemiology Center, 711Central Ave suite 220, Billings, MT 59102, USA

3Project Director, Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council Epidemiology Center, 711 Central Ave suite 220, Billings, MT 59102, USA

Submission: April 12, 2018; Published: April 23, 2018

*Corresponding author: Mike Andreini MPH, Director, Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council Epidemiology Center, 711Central Ave suite 220, Billings, MT 59102, USA, Email: mike.andreini@rmtlc.org

How to cite this article: Allyson Kelley, Mike Andreini, Dyani Bingham. Assessing the Tribal Public Health Workforce Needs in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho: Results from the Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council Epidemiology Center. JOJ Nurse Health Care. 2018; 7(3): 555715. DOI: 10.19080/JOJNHC.2018.07.555715

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Abstract

Objective: To document the tribal public health workforce needs in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho.

Methods: We designed a tribal public health workforce needs assessment (WNFA) using the Association of State and Territorial Health Organizations workforce survey methodology. The final survey was sent to 13 tribal public health organizations located in the Rocky Mountain Region in November 2016.

Results: Thirty tribal public health workers from nine tribal organizations (69%) completed the assessment. WFNA findings show that tribal public health workers are not compensated at the same rate as non-tribal public health professionals. Tribal professionals were less likely to have college degrees and report greater public health training needs than their national counterparts.

Conclusions: Tribal public health workers are committed to their communities and improving public health despite lower pay and uncertainty in public health program funding

Keywords: American Indian, Tribal Public Health Workforce Development, Tribal Health

Abbreviations: ASTHO: Association for State and Territorial Health Organizations; NACCHO: National Association of County and City Health Officials; CHRs: Community health representatives; TEC: Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council Epidemiology Center; RMPTHC: Rocky Mountain Public Health Training Center; WFNA: Workforce Needs Assessment

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Policy Implication's

Tribal public health workers play a critical role in closing the health disparities gap among American Indian populations. Policies that increase funding for core public health competencies while providing access to degree completion programs for tribal public health workers are needed. The national public health workforce is shrinking in the U.S. There are 50,000 fewer public health workers in the U.S. today compared to 20 years ago [1]. The growing US population and the number of public health workers reaching retirement is a crisis-by 2020 ASTHO estimates the U.S. will need 250,000 more public health workers [1]. Previous studies by HRSA [2] found that the public health workforce was decreasing in relation to the growth of the US population. Other national public health organizations like the Association for State and Territorial Health Organizations (ASTHO) [3] and the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) report similar concerns about the shrinking public health workforce and the need for legislation to increase program funding for public health workers [4].

Public health workers are vital to the nation's health and include a number of specialties including public health physicians, public health nurses, first responders, social workers, community organizers, advocacy specialists, laboratory workers, health educators, nutritionists, epidemiologists, and environmental health workers. Public health workers are tasked with prevention in areas like obesity, chronic disease, injuries, mental illness, infectious disease, surveillance, and emergency preparedness. Training public health workers is a critical component of effective public health systems and previous studies have found that most public health workers need training in core public health competency areas [5-6]. There is consensus among state, federal, and local public health policy makers about how to develop the public health workforce, however; previous studies and reports have failed to include tribal public health workers. Tribal public health workers are different than non-tribal public health workers. First, the integration of culture and traditional approaches into public health is unique. Community health representatives (CHRs) exemplify this uniqueness (or simily) with work that incorporates traditional health into prevention and community outreach activities. CHRs often speak the Native language and travel great distances to reach rural and isolated tribal members. They also provide transport to and from doctors' appointments and provide support to tribal members in need. Second, many tribal public health positions are funded by grants and "soft” money or limited funding from the Indian Health Service. Third, tribal public health workers often live and work in tribal nations that are sovereign governments with rights to self-determination. As sovereign nations, tribes exercise authority via rules, regulations, and codes to implement and sustain public health. Examples of tribal public health codes and regulations include water protection and quality, protection of culturally sensitive areas, fire prevention to protect tribal resources, the control of infection disease and vectors, open burning, domestic violence, elder abuse, animal control, sanitation, wastewater, traffic, and food vendor sanitation. Tribes are challenged with implementing and enforcing public health codes due to limited staffing, funding, and infrastructure. Without codes and regulations, tribal public health is at risk. Finally, the unique history and funding status of the Indian Health Service contributes to differences in how tribal public health workers are trained, recruited, compensated, and retained over time.

In 1954 the Secretary of the Interior transferred all health program personnel of the Bureau of Indian Affairs to the Surgeon General of the United States Public Health Service. The Indian Health Service was established in 1955 and is the principal federal health care provider and health advocate for American Indian people. The Indian Health Service public health focus includes multiple programs in 12 regions of the United States: clinical and preventive services, information technology, public health support, and environmental health and engineering. These programs employ more than 15,000 employees in tribal communities and Indian Health Service Area locations at 600 facilities throughout the U.S. In 2016, the Indian Health Service budget appropriation was $4.8 billion [7] and the actual budget needs exceed $32 billion [8]. In 1994 Congress passed legislation to extend tribal self-governance to allow tribes to contract public health programs, services, and functions at the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Indian Health Service. In 2016, $1,873, 825 of the $4,727,000 total Indian Health Service budget funds tribal self-governance programs. Tribes receive contract funds to implement public health programs and this has been a critical step in honoring the sovereignty of tribal nations. However, tribes are challenged to implement public health programs because funding is not sufficient to meet the needs of American Indian people. The Indian Health Service per capita expenditures for patient health services were just $2,834, compared to $9,990 per person for health care spending nationally [8]. Persistent funding shortfalls at the Indian Health Service, staffing shortages, aging infrastructure, rural and isolated locations have led to major gaps in developing public health infrastructure and capacity at the tribal level. These gaps also contribute to the health disparities that American Indian people experience.

Efforts to reduce health disparities in American Indian communities have not been as effective as they need to be. American Indians born today have a life expectancy that is 4.4 years less that the US population (73.7 vs. 78.1) [9]. In Montana, one state in the Rocky Mountain Region, these disparities are even more pronounced, with the average life expectancy 20 years less for American Indian women and 19 years less for American Indian men [10]. The leading causes of death among American Indians include diseases of the heart, malignant neoplasms, unintentional injuries, chronic lower respiratory diseases, and diabetes mellitus [11]. Other social determinants that contribute to health disparities in American Indian communities include loss of culture, loss of language, persistent poverty, limited access to quality education, discrimination, and poor access to quality healthcare [12-13]. Tribal public health workers who live and work in their communities play a critical role in addressing health disparities previous studies have found that when communities are involved, public health improves [14]. Yet, tribal public health workers are often excluded from national, state, and local public health workforce initiatives and assessments. This report seeks to fill this gap and is based on the 2016 Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council Epidemiology Center (TEC) tribal public health workforce needs assessment.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Methods

The TEC received funding from the Rocky Mountain Public Health Training Center (RMPTHC) to develop and implement a 2-phase tribal public health workforce needs assessment (WFNA). During phase 1 (July 2016), TEC met with state, local, and tribal area public health professionals to learn about the kinds of training opportunities available through the RMPTHC. TEC presented information about the unique needs of the tribal public health workforce to the RMTPHC advisory committee in August 2016. TEC reached out to the ASTHO Officials to review results from the 2015 Public Health Workforce Needs Assessment. After reviewing national and state-level public health workforce assessment reports, TEC developed the tribal public health WFNA with input from tribal leaders, health directors, and workers. Additional questions were added to address contextual factors including: poverty and rural locations of reservations, unique funding status of Indian Health Service and tribal 638 programs, historical and present-day trauma, and holistic approaches to public health service delivery. The final 25-question survey included multiple choice, text response, and Likert-type scale ratings. During phase 2, TEC worked with tribal leaders and health directors to implement the WFNA. This process included multiple communications and outreach:

a) Emails to all tribal health directors, urban health center directors, Billings Area Indian Health Service directors, and select tribal leaders

b) Follow-up phone calls

c) In-person meetings and

d) Posting WFNA online using Qualtrics to increase participation. In phase 2 (November 2016) the WFNA was completed by tribal health professionals over a 30-day period.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Results

This project was designed to document the tribal public workforce needs among tribal public health organizations in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. Results from this assessment illustrate the strengths of the tribal public health workforce and highlight the training preferences, competencies, and needs of tribal public health workers. The Billings Area's 2016 User Population is estimated at 72,664. Public health services are provided by six (6) Federal Service Units: Blackfeet (Heart Butte), Crow (Pryor, Lodge Grass), Ft. Belknap (Hays), Ft. Peck (Wolf Point), Northern Cheyenne, Wind River (Ft. Washakie), five (5) Urban health programs and two (3) tribally operated health programs [15,16]. TEC also serves the Shoshone Bannock Tribes of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in Idaho and their 5,300 members. We reached out to tribal public health programs and urban Indian centers in these locations. Of the 13 programs located in these locations, nine completed the WFNA. Seven programs were reservation-based tribal public health programs in Montana or Wyoming, one was an urban Indian health center in Montana, and one program was the Billings Area Indian Health Service.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

Thirty tribal public health professionals completed the WFNA. The majorities were American Indian (86.6%), others were White (13%) or multiple ethnicities (3%). English was the primary language spoken (96%) followed by Native language (20%) and other (3%). Just 13.6% of tribal public health professionals were 40 years of age or younger. Half of the tribal public health professionals surveyed make less than $45,000 per year. Educational attainment varied: high school diploma (3.4%), associates (27.5%), bachelors (44.8%), masters (13.7%), doctorate (0.0%), and prefer not to answer (10.3%). More than 43% of tribal public health professionals attended tribal colleges. Most tribal public health professionals were employed by tribal public health programs (83.3%) followed by an urban Indian organization (13.3%) and other (33%). Most positions are funded by 638 program funds (48.3%) or grant program funds (37.9%). Few positions are funded by other federal or tribal program funds (<41%).Most tribal public health professionals plan to stay in their current job indefinitely (73.3%) and this is considerably higher than the national public health workforce where just 57% plan to stay indefinitely. Public health professionals are relatively new in their positions with more than half reporting less than five years in their current health organization. More than one- third of WFNA respondents represent health education and health promotion public health professions and 70% worked for tribal organizations. Most professionals were satisfied with their current job and employer (83.6%) and satisfied with their pay (80.0%).

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Public Health Competencies

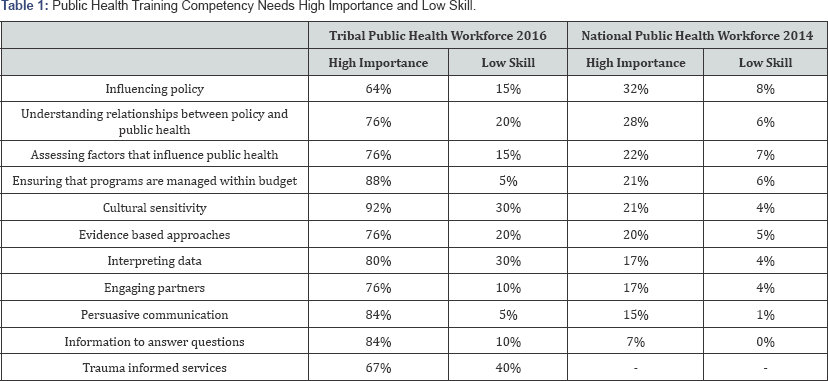

Public health training competencies appear in Table 1. Cultural sensitivity and managing program budgets ranked highest for their level of importance among tribal public health professionals. In comparison, the national public health workforce ranked influencing policy and understanding relationships between policy and public health as most important. Tribal professional's report that interpreting public health data to answer questions and inform future efforts is very important (80%) but report limited skills in this area (30%), national public health workers felt that was not as important (17%) and just 4% reported this was a low-skill area. Using trauma informed public health services was ranked as highly important (67%) and a low skill area among respondents (40%). Due to the prevalence of trauma in American Indian communities, this survey question was added by the TEC, comparison data are not available. Overall, tribal public health workforce members report lower skills in all competencies areas and at the same time felt these competencies were highly important.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

Professionals surveyed feel that recruitment and retention of qualified tribal members as public health professionals is greatest need facing the work force (50%) followed by leadership and systems thinking (38%). Nearly half (46%) of professionals feel the greatest strength of the tribal public health workforce is providing access to public health services in rural and isolated communities. More than one-third (34%) of professionals felt the diverse partners and programs are the greatest strength.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Training Preferences

To understand more about the training preferences ofthe tribal public health workforce, the WFNA presented a list of training modalities and asked respondents to rate their preferences. More than half (64%) of professionals ranked in-person trainings in their communities as their number one choice. In-person trainings in another location or community were ranked second followed by video webinars, self-study and independent learning, and online learning modules. The least preferred training format was one-on-one training with an instructor. The majority of workers report they can use work hours to participate in trainings, attend on-site trainings. Most work for organizations that will pay their travel and training registration fees (<84%). More than half of workers surveyed reported that their organization did not require continuing education or include education and training in annual reviews.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Compensation

Tribal public health professional's salaries may reflect shortages in Indian Health Service funding. Tribal workers make significantly less than their national counterparts, half of tribal professional’s report making less than $45,000 per year compared to just 25% of public health workers across the nation [17]. Tribal public health workforce policies around financing are of utmost importance and more than one-third of public health positions were funded with soft money. Despite the lower pay, most tribal workers are committed to staying in their positions indefinitely.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Limitations

The current WFNA results do not represent every tribe or urban health center in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. The non response of tribal public health agencies and professionals limits the generalizability of results. Similarly, the WNFA results do not represent every tribal public health discipline and profession. Although the TEC attempted to follow the 2014 national ASTHO survey methodology, there were differences in how the survey was administered and an additional question about trauma was added to the tribal public health training competencies. Despite these limitations, we feel that this report illuminates the strengths and needs of tribal public health workforce members.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Discussion

The WNFA was developed based on established public health core competences that are essential for assessing and improving tribal public health worker skills and practice. The results of this assessment have several important implications. First, it is necessary to address the lower educational attainment among American Indians. This coupled with persistent poverty; trauma, violence, and discrimination create challenging conditions for strengthening the public health workforce. Degreed tribal public health workers are needed to address health disparities in American Indian communities, however efforts to bridge the educational gap have not been as successful as they need to be. In Montana, 14% of American Indians are college graduates compared with 29% of Whites [18]. Current research on American Indian students who graduate from high school and attend a public college report that American Indian students have the highest dropout rate of any student population. Tribal colleges are a key solution for addressing retention issues in American Indian students-one report indicates that when American Indian students attend tribal colleges, they are eight times less likely to drop out of college [19]. Renewed efforts are needed that support American Indian students as they transition from high school, to college, and career. Second, a range of interrelated, comprehensive training agendas and policies will strengthen the public health workforce, including

a) Workforce development strategies for tribal public health workers, including on-the-job training and career development;

b) The development of sustainable funding for training and career development;

c) Delivering training in a manner that is culturally responsive to the needs of tribal members, this includes inperson in tribal communities; and

d) A comprehensive training agenda focused on the areas of greatest need including culturally responsive service delivery,trauma informed approaches, and interpreting public health data.

Professionals report that their organizations will pay for training costs, but there may not be an impetus to attend trainings if continuing education and training are not required. Tribal public health organizations may consider including continuing education and training requirements in the annual review process, even when professionals do not require continuing education for professional certification. Third, efforts that streamline public health competencies and accreditation of tribal public health programs may help clarify roles of tribal public health workers and agencies in relation to state, federal, county, and local public health agencies. Accreditation may also help increase access to credentialing, certification, and registration opportunities for tribal public health workers. Such opportunities will support tribal public health professionals as they demonstrate mastery and skills for select public health professions [19]. Fourth, increased funding for public health policy development (including laws, codes, regulations, and enforcement) will strengthen public health infrastructure for tribes. Public health infrastructure is critical for tribes as sovereign nations. Federal agencies like HRSA, the Bureau of Health Workforce, and the Indian Health Service may use WFNA results as a guide to focus tribal public health workforce development and core public health competencies through educational training programs and instructional delivery methods highlighted in the WFNA.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Conclusion

The WFNA provides insight into the tribal public health workforce in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. The TEC feels that documenting the strengths and needs of the tribal public health workforce is the first step in improving public health for tribal members in the Rocky Mountain Region. Variations in how public health is funded by the Indian Health Service at the tribal level may explain some differences observed in the WFNA. It is possible that chronic funding shortfalls at the Indian Health Service have translated into lower pay and fewer jobs among tribal public health workers. Lower educational attainment among tribal public health workers is likely due to the legacy of colonization, forced relocation, boarding schools, and trauma which has left an enduring impact on American Indian communities. Despite this legacy, American Indian tribal public health workers continue to thrive while providing essential public health services to their communities-WFNA results indicate they are resilient and dedicated. Unlike the national public health workforce, the majority of tribal public health workers plan to say in their current positions indefinitely. Tribal public health professionals report that through their work, they are able to help their people live healthier lives. The sense of connection and community that tribal public health professionals feel cannot be measured in terms of degrees, salaries, competencies, or funding. Results from the WFNA provide a roadmap for future training and skill building for tribal public health workers. These results underscore the need for advocacy around public health funding, pipe-line programs that support American Indian students in their educational endeavors, advocacy related to trauma-informed public health practice, and continued support for culturally-responsive public health services.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

Public Health Implications

A skilled tribal public health workforce is one of the most effective tools for ensuring that tribes have access to quality health related services. Maintaining the current tribal public health workforce is challenging due to limited funding, lower pay, remote and isolated locations, and funding positions with soft money. Efforts to engage the tribal public health workforce at state, federal, and county public health organizations will reduce health disparities while promoting population health and well-being for all. Identifying critical public health infrastructure to provide services is also needed. Creating a pipeline of public health workers in American Indian communities is needed, where community members complete degrees in public health fields and then returns to their communities to provide critical public health services.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Policy Implication's

- Methods

- Results

- Characteristics of Tribal Public Health Workforce Surveyed

- Public Health Competencies

- Tribal Public Health Workforce Characteristics

- Training Preferences

- Compensation

- Limitations

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Public Health Implications

- References

References

- Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (2017) Public Health Workforce Position Statement.

- Gebbie, Kristine M (2000) The public health work force: enumeration 2000. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, National Center for Health Workforce Information and Analysis.

- Association of State and Territorial Health Official (2015) State Public Health Employee Worker Shortage Report: A Civil Service Recruitment and Retention Crisis.

- Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (2005) Strategies for Enumerating the Public Health Workforce.

- National Association of County and City Health Officials (2006) Project Public Health Ready.

- Hernandez Lyla M, Linda Rosenstock, Kristine Gebbie (2010) Who will keep the public healthy? educating public health professionals for the 21st century. National Academies Press, USA.

- Indian Health Service (2017) Health Disparities Factsheet.

- (2017) Health and Human Services FY 2019 Tribal Budget Consultation. National Indian Health Board.

- (2017) Disparities in American Indian Health Fact Sheet. Indian Health Service.

- (2013) The State of the State's Health: A report on the Health of Montanans. State of Montana Department of Health and Human Services.

- (2017) Mortality Disparity Rates. Indian Health Service.

- King, Malcolm, Alexandra Smith, Michael Gracey (2009) Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. The Lancet 374: 76-85.

- Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, Mohammed SA (2008) Moving upstream: how interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. Journal of public health management and practice 14(Suppl): S8-17.

- Michael YL, Farquhar SE, Wiggins N (2008) Findings from a community- based participatory prevention research intervention designed to increase social capital in Latino and African American communities. J Immigr Minor Health 10(3): 281-289.

- (2017) Budget Priorities 2019 Billings Area. Billings Area Indian Health Service Report.

- Association for State and Territorial Health Officials (2005) Information to Action: The workforce data of public health WINS.

- American Indian Community Survey (2006) Montana Quick Facts.

- Gebbie, Kristine M, Bernard J Turnock (2006) The public health workforce, 2006: new challenges. Health Affairs 25(4): 923-933.

- Wolf, Patterson Silver, David A, Sheretta T (2017) Butler-Barnes, and Van Zile-Tamsen. 'American Indian/Alaskan Native College Dropout: Recommendations for Increasing Retention and Graduation.” Journal on Race, Inequality, and Social Mobility in America 1(1): 1-15.