Differential Item Functioning of the Arabic Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21)

Amira Mohammed Ali1* and Joseph Green2

1Department of Psychiatric Nursing and Mental Health, Alexandria University, Egypt

2School of Public Health, University of Tokyo, Japan

Submission: September 18, 2017; Published: September 27, 2017

*Corresponding author: Amira Mohammed Ali, Department of Psychiatric Nursing and Mental Health, Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University, Edmon Fremon St, Smouha, Alexandria, 36741, Egypt, Tel: +203-4291-578; Email: mercy.ofheaven2000@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Amira M A, Joseph G. Differential Item Functioning of the Arabic Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21). JOJ Nurse Health Care. 2017; 4(5): 555646. DOI: 10.19080/JOJNHC.2017.04.555646

Abstract

Psychological distress is a correlate of both physical and mental problems; therefore the need for sound distress measures is intense. This study investigated the validity of the Arabic version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) in 149 Egyptian drug users by examining its items for differential item functioning (DIF) across subgroups of age, gender, etc. More than half the items exhibited DIF. These items apparently reflect on other factors such as age and gender groups instead of depicting experienced degree of psychological distress. Further examinations in larger and diverse samples are needed.

Keywords: Construct validity; DASS-21; Differential item functioning; Drug users; Substance related disorders

Introduction

Symptoms of depression and anxiety are widespread, chronic, and recurrent; their recovery is poor. They are associated with decreased work productivity, dissatisfaction in social relations, low quality of life, and high risk of suicide [13]. Negative emotions play a major role in the development and continuation of substance use disorders (SUDs) [4]. Individuals turn to illicit drugs to achieve emotional-regulation i.e., to cope with depression, anxiety, anger and trauma; and cover up their poor social skills [5,6]. Evidence indicates that adolescents with both recent and chronic depression and anxiety are more likely to use illicit drugs in the future [7,8]. Correspondingly, use of illicit drugs in adolescence is associated with higher psychological distress and continued drug use in adulthood [9]. Furthermore, withdrawal symptoms, intensity and frequency of craving, failure of pharmacotherapy, and relapse increase during emotional distress, even during and after treatment [10,11]. Conversely, drop of negative emotions during treatment is associated with less use of drugs [12].

Early identification of youth with high emotional negativity is necessary in order to provide timely protective measures to prevent future onset of debilitating life-long mental problems such as drug use [2]. Similarly, it is crucial to address negative affect among drug users so as to enhance treatment outcomes and lower relapse [11]. Symptoms of depression and anxiety can go unnoticed; therefore, rigorous measures are needed to identify those with high levels of psychological distress [13]. Several measures of depression and anxiety exist. However, the overlap of both symptoms throws doubt on the discriminant validity of standalone depression or anxiety measures [14]. The Depression Anxiety Stress scale (DASS) was designed to minimize measurement overlap by measuring the distinct features of depression and anxiety and to [15]. Its three subscales depict symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress (which is common in both depression and anxiety) [16]. Hence, it measures a distinct syndrome-emotional distress [17,18]. It is broadly used to assess symptoms severity and response to treatment [14,15]. The full version has sound psychometric qualities; but reports on the psychometrics of the 21 items DASS are inconsistent, especially in translated versions [15,19-21].

Validation testing addresses the implications of scores with respect to the presumed underlying latent trait [22]. DASS scores will be less useful if people respond to them on the basis of other factors that those scorers are not intended to reflect, such as age and gender [13,23]. Differential item functioning (DIF) means that individuals in different subgroups defined by such extraneous factors will respond differently to a given question despite having the same level of the latent trait [24]. For example, at high levels of anxiety, those without obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) were more likely to endorse 'dry mouth' and 'heart beat without effort', compared to those with OSA i.e., both items caused overestimation of the latent trait [25]. This is known as uniform DIF- DIF is the same for all trait levels of the two groups. Non-uniform DIF occurs when there is an inconsistent between- group difference in the likelihood of endorsing an item across levels of the latent trait [26].

Although the Arabic DASS-42 was tested in Australia among Arab immigrants of different nationalities [27]; psychometric evaluations of the Arabic DASS-21 are deficient. To bridge that gap, here we report the results of differential item functioning analysis of the DASS-21 in a sample of Egyptian drug users. In this study, we assume that all participants rate DASS-21 items according to their corresponding level of the latent trait (emotional distress). We hypothesize that items do not show DIF between different subgroups.

Material and Methods

This study involves a secondary analysis of a dataset collected from 149 inpatient Egyptian drug users. Description of the procedure is available elsewhere [28]. The original study was approved by Alexandria University board of research ethics.

Instrument

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) [29] consists of 3 subscales; each subscale comprises 7items. The subscales assess depressive symptoms (e.g. life was meaningless), anxiety symptoms (e.g. finding it difficult to relax), and general stress symptoms (e.g. feeling rather touchy). Items are reported on a 4-point scale (0 = did not apply to me at all and 3 = applied to me most of the time). Higher scores signify severe psychological distress.

Statistical Analysis

We examined the DASS-21 for differential item functioning (DIF) by age, gender, marital status, education, employment, income, chronicity, length of the hospital stay, and history of mental illness. For this purpose, we used a macro developed by IBM that performs a set of 3 ordinal logistic regressions for each item [30]. In the first step, each item's score was regressed on the DASS-21 total score. In the second step, each item's score was regressed on a group variable (see Table 1 for subgroups). In the third step, the regression equation included a term for the interaction between the group variable and the DASS-17 total score. Then, the criterion of Jodoin & Gierl [31] was used to detect DIF. Specifically, DIF was judged to be present if the effect size (ES) of an item with a statistically significant x2 statistic was at least 0.035. Effect sizes were computed by subtracting the pseudo-R2 obtained in the third step from those obtained in the first step [31]. Data were analyzed in SPSS version 22, and the level of significance was set to 0.05 two-tailed.

Results

Participants' characteristics

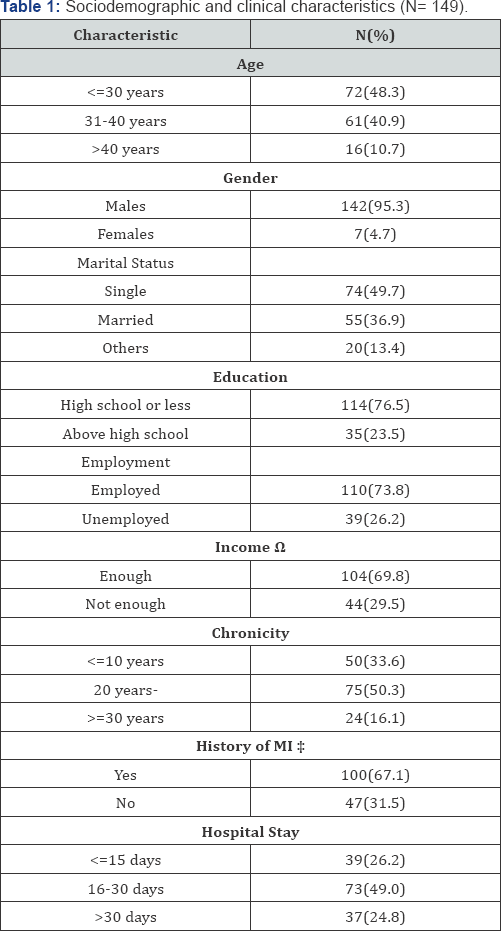

The majority of the participants were men (95.3%). The mean age was 32.5 years (SD= 6.8 years, age range: 19-60 years). Participants reported abuse of several drugs; however, heroin, pharmaceutical agents, and cannabis were the most frequently abused drugs (80.5%, 79.2%, and 75.2%, respectively) (see Table 1 for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants).

Ω1 missing observation, ‡ 2 missing observations

Differential items functioning

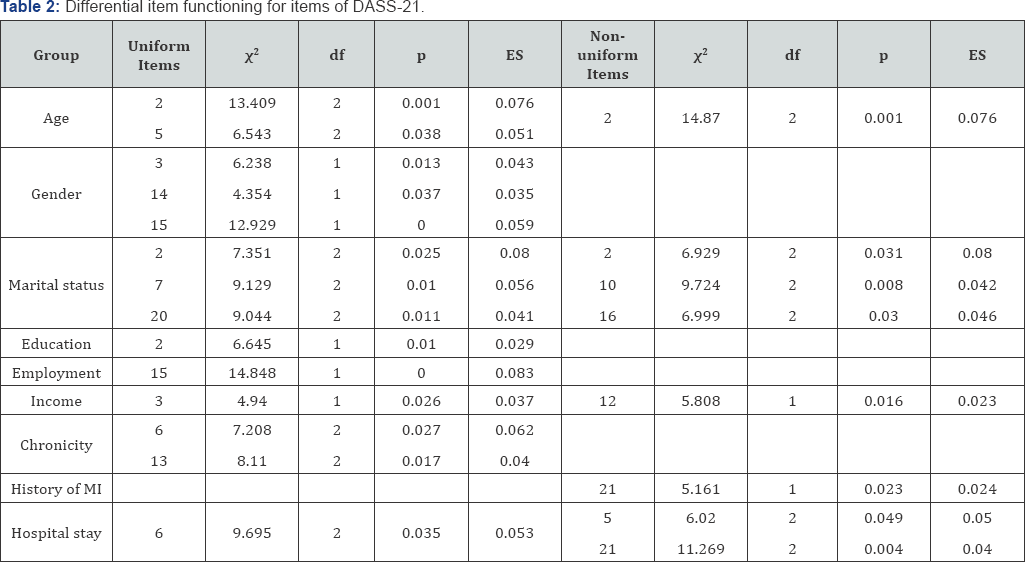

Table 2 shows that more than half the items exhibited some DIF. Items 2 and 5 had a uniform DIF by age; whereas those less than 30 years significantly endorsed item 2. Meanwhile, items 3, 14, and 15 had uniform DIF by gender. Items 2, 7, and 20 had a uniform DIF by marital status. It was significantly easier for widow and divorced to endorse items 2, and 16; whereas married and single significantly endorsed item 10.Items 6 and 13 significantly inflated DASS-21 total score by chronicity. The effect size was negligible for item 2 by education, item 12 by income, and item 21 by history of mental illness. Item 6 had uniform DIF by the length of hospital stay. Item 5 showed a marginally significant interaction effect among those with a hospital stay of less than 2 weeks; however the effect size was moderate 0.050.Meanwhile, it was significantly easier for those hospitalized for 2-4 weeks to endorse item 21. Obviously, item 2 exhibited higher DIF compared to other items.

Discussion

This study is an initial attempt to examine the potentials of the Arabic DASS-21. More than half the items showed variance between different subgroups. Such DIF indicates that the DASS- 21 involves systematic errors. The main effect was inflated for some items among some groups.

The literature embroils disagreement on the psychometric properties of DASS-21 [19,32-35]. Consistent with the current study, nationality affected the performance of items of the DASS- 21: the Chinese version had lower differentiation between depression and anxiety compared to the English scale. Further, its discrimination was lower among Australian-Chinese compared with Chinese samples in Hong Kong [36]. In accordance, Shea et al. [2] reported DIF by gender for items 13 and 16 among adults attending a stress resilience program. Similarly, another study reported some DIF in all the DASS-21 subscales; 2 items on the anxiety subscale significantly lowered the severity scores of obstructive sleep apnea [25].

The higher incidence of DIF noticed in our study can be because we examined both uniform and non-uniform DIF across 8 grouping variables while the other studies usually described uniform DIF and used only two or three grouping variables. In addition, the samples were different (English speaking). The large number of items that had DIF indicates scale errors that were not caused by chance. Other factors such as gender were a source of bias that caused failure of these items to accurately reflect the latent trait.

In case of DIF, some corrective actions should follow (e.g., removal of problematic items).Considering that 50% of the items had DIF, all these problematic items need further revision. We recommend future studies to examine DASS-21 in larger and diverse samples, and through robust techniques such as IRT to support decisions about eliminating dysfunctional items.

This study has some limitations. Data were prone to selfreport bias given the fact that the sample was small, few patients took part, their education was low, those who participated had a longer stay. In addition, only 7 females participated in the study; while the literature supports association between emotional negativity and gender.

References

- Shamsuddin K, Fadzil F, Ismail WS, Shah SA, Omar K, et al. (2013) Correlates of depression, anxiety and stress among Malaysian university students. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 6(4): 318-323.

- Shea TL, Tennant A, Pallant JF (2009) Rasch model analysis of the depression, anxiety and stress scales (DASS). BMC Psychiatry 9: 21.

- Farnam A (2011) The five factor model of personality in mixed anxiety – depressive disorder and effect on therapeutic response. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 4(4): 255-257.

- Piper ME, Cook JW, Schlam TR, Jorenby DE, Baker TB (2011) Anxiety diagnoses in smokers seeking cessation treatment: relations with tobacco dependence, withdrawal, outcome and response to treatment. Addiction 106(2): 418-427.

- McKernan LC, Nash MR, Gottdiener WH, Anderson SE, Lambert WE, et al. (2015) Further evidence of self-medication: personality factors influencing drug choice in substance use disorders. Psychodynamic Psychiatry 43(2): 243-276.

- Allan NP, Albanese BJ, Norr AM, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB (2015) Effects of anxiety sensitivity on alcohol problems: evaluating chained mediation through generalized anxiety, depression and drinking motives. Addiction 110(2): 260-268.

- Measelle J, Stice E, Springer DW (2006) A prospective test of the negative affect model of substance use and abuse: moderating effects of social support. Psychol Addict Behav 20(3): 225-233.

- Cerda M, Bordelois PM, Keyes KM, Galea S, Koenen KC, et al. (2013) Cumulative and recent psychiatric symptoms as predictors of substance use onset: does timing matter? Addiction 108(12): 21192128.

- Green KM, Zebrak KA, Robertson JA, Fothergill KE, Ensminger ME (2012) Interrelationship of substance use and psychological distress over the life course among a cohort of urban African Americans. Drug Alcohol Depend 123(1-3): 239-248.

- Hogarth L (2015) Negative mood reverses devaluation of goal- directed drug-seeking favouring an incentive learning account of drug dependence. Psychopharmacology 232(17): 3235-3247.

- Witkiewitz K, Villarroel NA (2009) Dynamic association between negative affect and alcohol lapses following alcohol treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol 77(4): 633-644.

- McKay JR (2011) Negative mood, craving, and alcohol relapse: can treatment interrupt the process? Current psychiatry reports 13(6): 431-433.

- Parkitny L, McAuley JH, Walton D, Pena Costa LO, Refshauge KM, et al. (2012) Rasch analysis supports the use of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales to measure mood in groups but not in individuals with chronic low back pain. J Clin Epidemiol 65(2): 189-198.

- Norton PJ (2007) Depression anxiety and stress scales (DASS-21): Psychometric analysis across four racial groups. Anxiety Stress Coping 20(3): 253-265.

- Oei TPS, Sawang S, Goh YW, Mukhtar F (2013) Using the depression anxiety stress scale 21 (DASS-21) across cultures. Int J Psychol 48(6): 1018-1029.

- Henry JD, Crawford JR (2005) The short-form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 44(Pt 2): 227-239.

- Tonsing KN (2014) Psychometric properties and validation of Nepali version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21). Asian J Psychiatr 8: 63-66.

- Osman A, Wong JL, Bagge CL, Freedenthal S, Gutierrez PM, et al. (2012) The depression anxiety stress scales-21 (DASS-21): further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. J Clin Psychol 68(12): 1322-1338.

- Tran TD, Tran T, Fisher J (2013) Validation of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) 21 as a screening instrument for depression and anxiety in a rural community-based cohort of northern Vietnamese women. BMC Psychiatry 13: 24.

- Nur Azma B, Rusli BN, Quek KF, Noah RM (2014) Psychometric properties of the malay version of the depression anxiety stress scale-21 (M-DASS21) among nurses in public hospitals in the Klang Valley. Int J Collab Res Intern Med Public Health 6(5): 109-121.

- Daza P, Novy DM, Stanley MA, Averill P (2002) The depression anxiety stress scale-21: Spanish translation and validation with a hispanic sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 24(3): 195-205.

- Wellman HM, Liu D (2004) Scaling of theory-of-mind tasks. Child Dev 75(2): 523-541.

- Jafari P, Nozari F, Ahrari F, Bagheri Z (2017) Measurement invariance of the depression anxiety stress scales-21 across medical student genders. Int J Med Educ 8: 116-122.

- Gomez R (2013) Depression anxiety stress scales: factor structure and differential item functioning across women and men. Personality and Individual Differences 54(6): 687-691.

- Nanthakumar S, Bucks RS, Skinner TC, Starkstein S, Hillman D, et al. (2016) Assessment of the depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS- 21) in untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Psychol Assess.

- Nathanson C, Paulhus DL (2017) A Differential item functioning (dif) analysis of the self-report psychopathy scale. Poster presented at the 1st biannual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Psychopathy, Vancouver, BC, Canada, pp. 1-12.

- Moussa MT, Lovibond P, Laube R, Megahead HA (2016) Psychometric properties of an arabic version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS). Research on Social Work Practice 27(3): 375-386.

- Ali AM, Ahmed A, Sharaf A, Kawakami N, Abdeldayem SM, et al. (2017) Analysis of the Arabic version of the depression anxiety stress scale-21: cumulative scaling and discriminant validity testing. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 30: 56-58.

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH (1995) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd edn). Psychology Foundation, Sydney, Australia.

- IBM Support (2017) Obtaining likelihood-ratio tests for differential item functioning (DIF) in IBM SPSS Statistics.

- Jodoin MG, Gierl MJ (2001) Evaluating type i error and power rates using an effect size measure with the logistic regression procedure for DIF detection. Applied Measurement in Education 14(4): 329-349.

- Asghari A, Saed F, Dibajnia P (2008) Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety stress scales-21 (DASS-21) in a non-clinical Iranian sample. International Journal of Psychology 2(2): 82-102.

- Mahmoud SRJ, Hall LE, Staten RT (2010) The Psychometric properties of the 21-item depression anxiety stress scale (DASS-21) among a Sample of young adults. Southern Online Journal of Nursing Research 10(4).

- Gloster AT, Rhoades HM, Novy D, Klotsche J, Senior A, et al. (2008) Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety and stress scale-21 in older primary care patients. J Affect Disord 110(3): 248-259.

- Patrick J, Dyck M, Bramston P (2010) Depression anxiety stress scale (DASS): Is it valid for children and adolescents? J Clin Psychol 66(9): 996-1007.

- Moussa MT, Lovibond PF, Laube R (2017) Psychometric properties of a chinese version of the 21-item depression anxiety stress scales (DASS21). pp. 1-29.