Nurses' Attitudes towards Research and Evidence-Based Practice: Perspectives from Psychiatric Setting

Xie HT *, Zhou ZY, Xu CQ, Ong S and Govindasamy A

Institute of Mental Health, Singapore

Submission: July 28, 2017;Published: August 28, 2017

*Corresponding author: Dr Xie Huiting, Institute of Mental Health, Buangkok Green Medical Park, Singapore, Tel: +65 33892522; Email: : hui_ting_xie@imh.com.sg

How to cite this article: Xie HT , Zhou ZY, Xu C, Ong S, Govindasamy A. Nurses' Attitudes towards Research and Evidence-Based Practice: Perspectives from Psychiatric Setting. 2017; 3(5): 555624. DOI: 10.19080/JOJNHC.2017.03.555624

Abstract

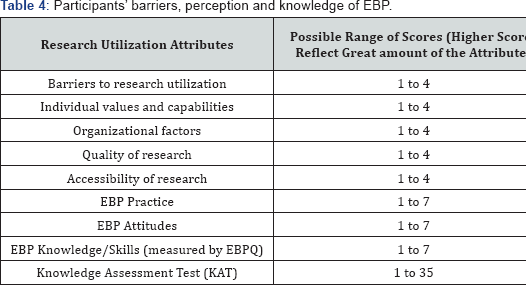

Despite the positive influence of research utilization on patient outcomes, the literature suggests that nurses’ engagement in evidence- based practices (EBP) can be improved. This study aims to understand nurses’ reservation about EBP, by examining their barriers, perception and knowledge in EBP and the factors influencing these. A descriptive survey was conducted on 68 nurses with at least one year of working experience. Their perception of EBP was measured by the Barriers to Research Utilization Scale (BARRIERS) with scores ranging from 1 to 4, and the Evidence Based Practice Questionnaire (EBPQ) with scores ranging from 1 to 7.

Objective measurement of EBP knowledge was attained via the Knowledge Assessment Test (KAT) with scores ranging from 1 to 35. Higher scores reflected greater barriers, EBP perception and knowledge. Nurses reported minimal barriers to research utilization (BARRIERS M=2.70, SD=0.40) and perceived EBP moderately with mean scores ranging from 4.14 to 4.93 on the various sub-scales. However, they scored relative low on KAT, (M=14.06, SD= 3.86) suggesting the lack of EBP knowledge. KAT scores were influenced by prior EBP involvement, t (58)=2.41, p=0. 02; and education level. ANOVA and post-hoc comparison showed that nurses with degree (KAT =15.15, SD = 3.88) had better EBP knowledge than nurses with diploma (KAT M=12.00, SD=2.81), F(3,58)=3.28, p = 0.03. In this study, data on nurses’ favourable perception of EBP was triangulated objectively with lowered knowledge scores. Findings may be utilized in the future development of learning platforms to hone nurses’ EBP knowledge.

Keywords: Nursing; Evidence-based practice; Evidence-based nursing; Attitudes; perception; Knowledge

Introduction

Evidence based practice (EBP) is widely recognized to be a core component in healthcare services. EBP is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of the best current evidence in making clinical decisions about the care of individual patients or groups. It requires the integration of individual clinical expertise and patient preferences with the best available clinical evidence from systematic research, and consideration of available resources [1]. In the mental health setting especially, EBP is important. Mental health practice may be misperceived as lacking the availability of laboratory test to diagnose mental illnesses and evaluate treatment outcome. Treatment decisions may be misperceived as developed through trial and error in layman's terms or through identification of patients' response. Evidence-practice gaps leading to underuse of proven therapies and overuse of inappropriate treatment is common in the mental health setting [2].

Thus, to enhance the scientific rigor of treatment in mental health settings and to transform the quality of mental health care, engaging mental health providers in EBP and improving the infrastructure for the provision of EBP are important [3]. EBP allows for the most effective clinical intervention in different types of patients and different clinical situations. It provides predictive information about treatment outcome and prognosis not only to healthcare providers, but also for the public and policy makers to gain confidence in mental health care. Routine mental health programs did not provide evidence-based practices to the great majority of patients with mental illnesses.

Nursing, as a scientific discipline requires its knowledge to be driven by the findings of research. EBP provides nurses with a method to use evidence that has been critically appraised and scientifically proven to deliver quality health care [4]. Despite this, the eivdence suggested that nurses base their clinical practice on research evidence last among various sources of knowledge. Of the 12 sources of knowledge on which nurses base their clinical practice on, evidence from research was ranked last by nurses [5]. They often faced difficulties in keeping up with the evidence [4] and frequently lacked time to review current evidence [6,7].

Moreover, the literature suggested that nurses infrequently engaged in evidence-based practices (EBP). Loyd [8] suggested that resistance to EBP stemmed from the distrust of the results of research study over safe, traditional practices [8]. The lack of support from professional colleagues and the lack of ability to obtain research findings in one's area of interest [5,8,9]were other barriers hindering nurses' involvement in EBP. The most common and most important obstacle is the inadequacy in knowledge regarding EBP. Accordingly to a survey done by Sigma Theta Tau, a reputable nursing society on 565 registered nurses, more than half of them, 69%, had only low to moderate knowledge of EBP and about 50% were not sure about the EBP process [6]. In addition, Salmond [10] proposed that the lack of continuous education and opportunity to practice EBP was a major obstacle towards EBP involvement [10]. For example, there were insufficient educational sessions for EBP due to lack of funding, staff and time. Therefore as time passed, nurses lost their knowledge of EBP and valuable treatments may never be utilized in clinical setting.

With the need for nurses to deliver care that is effective, safe, and efficient, the drive for EBP remains as one of the top priorities for nurses in various settings depite the barriers. Though a previous study conducted in the Singapore setting reported that nurses were limited in their ability to search and understand evidence, thus limiting their engagement in EBP, a dearth of studies on EBP engagement remains as majority of the studies were conducted in the western societies and in non-mental health setting. Before the creation of a vibrant EBP culture, it is important to gain an insight into nurses' perception of EBP. This study aims to understand nurses’ reservation about engaging in EBP, by examining the barriers, perception and knowledge in EBP and the factors influencing these in nurses working in psychiatric setting.

Materials and Methods

A descriptive survey was conducted on a convenience sample of 68 nurses in the only major public institution to enhance representativeness. Nurses registered with the Singapore Nursing Board as Registered Nurses and above, being employed full-time and with atleast one year experience. Enrolled nurse were excluded in view of their supportive roles to enhance homogeneity of sample.

Instruments

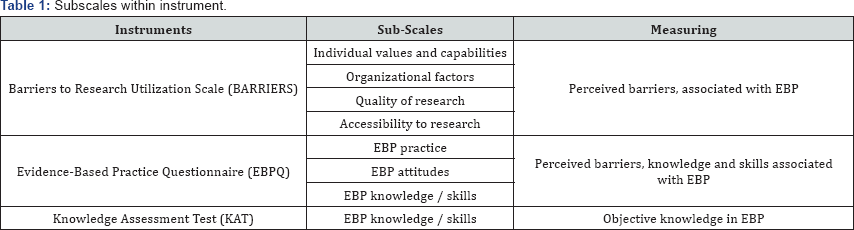

A number of instruments were employed in this study. Firstly, the Barriers to Research Utilization Scale (BARRIERS), a 29-items instrument assessed nurses' perceptions of barriers to the utilization of research findings in practice. The items were derived from the literature, giving it its content validity. This instrument had 4 subscales, namely characteristics of the nurse, characteristics of the organization in which the research will be used, characteristics of the innovation or research, and characteristics of the communication of the research. This instrument has been validated with a large sample of nurses. Good internal consistency was demonstrated with alpha coefficients of the subscales ranging from 0.70 to 0.80, indicating good reliability [11]. There are 4 response options for each item with scores ranging from 1 to 4. The scores of participants' responses to each item in the subscale are summed and divided by the number of items with valid responses (i.e., scores of 1 to 4), to obtain the mean score for each subscale. The higher the mean score, the greater the amount of barrier to utilizing research [11].

Secondly, the 24-items Evidence Based Practice Questionnaire (EPBQ) measured perceived competence in evidence based practice (EBP) on 3subscales namely, knowledge, practice and attitudes with scores on each item ranging from 1 to 7. Convergent validity was established by the strong correlation of this instrument with other measures of EBP knowledge and attitudes in prior studies. Internal consistency was high with alpha coefficients of 0.87 for the entire instrument. All items were scored on a scale of 1 to 7 and summed. A higher score indicated greater competence in EBP [12]. Thirdly, the Knowledge Assessment Test (KAT) developed by the research team with content validated by the nurse educators was used to provide an objective measurement of EBP knowledge with scores ranging from 1 to 35.

Data collection

Since this study involves human experimentation the study, all work was done in accordance with the appropriate institutional review body and carried out with the ethical standards. Following the attainment of ethical approval from the institutional review board, the list of all nurses working in the psychiatric institution was obtained. Information about the study was disseminated through internal email to these nurses. Nurses could express their interest to participate to members of the research team who would then screen them for their eligibility to participate. Researchers then met with the participants face to face to explain the procedures of the study, the benefits and risks to invite their voluntary participation. Instruments were then administered to participants to obtain the study data. To control for testing effects, the instruments were provided in the same sequence for all participants.

Statistical analysis

Upon completion of data collection, data was analyzed using Statistical Software Packages. SPSS v.22.standard data cleaning will be applied including screening the data for data-entry errors, checking for outliers, checking the extent and pattern of missing data and ensuring that appropriate assumptions are made as per the data analysis procedures. Descriptive statistics was then applied to describe the baseline characteristics of participants such as their age or gender and their scores on the instruments. Inferential statistics were then applied accordingly to discuss the factors influencing these scores. An alpha, a = 0.05 was used for all analysis.

Results

Participants' characteristics

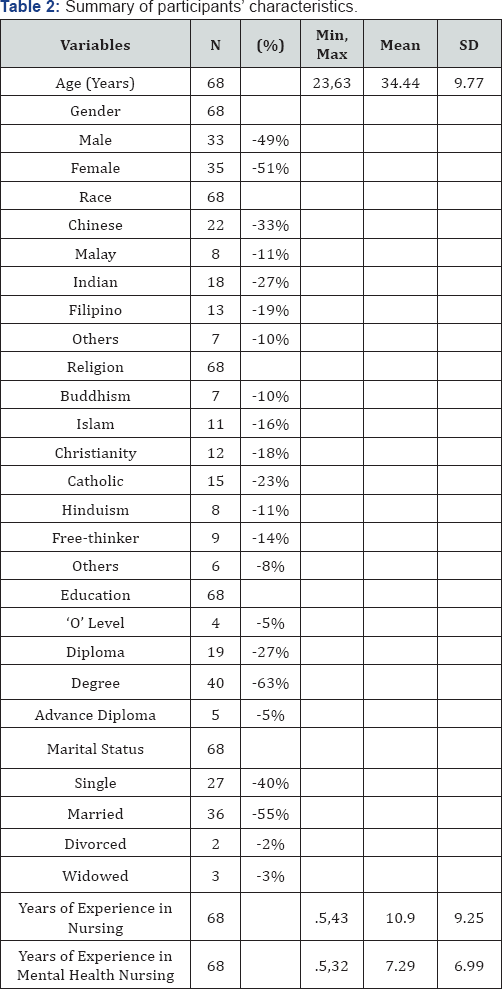

The mean age of participants is 35 years with a similar proportion of males and females included for this study. Majority of participants were Indian, married with degree as highest qualification. Their mean years of experience in nursing is 11 years while their mean years of experience in mental health nursing is 7 years (Table 1).

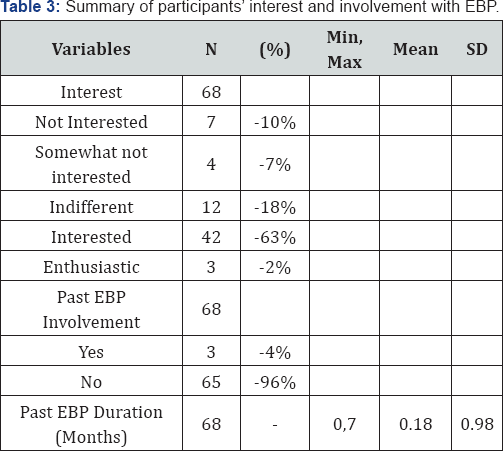

Overview of participants' barriers, perception and knowledge of EBP

Though majority of the participants in this study expressed interest in EBP, most of them have no past involvement in EBP. Even for those with past involvement, their mean involvement was less than a month for EBP (Table 2). It was noted that participants reported minimal barriers to research utilization (BARRIERS M=2.70, SD=0.40) and perceived EBP moderately with mean scores ranging from 4.14 to 4.93 on the various subscales. However, objectively, in the KAT test with possible scores ranging from 1 to 35, they scored relative low (KAT M=14.06, SD=3.85), suggesting a lack in EBP knowledge (Table 3).

Factors influencing participants' barriers, perception and knowledge of EBP

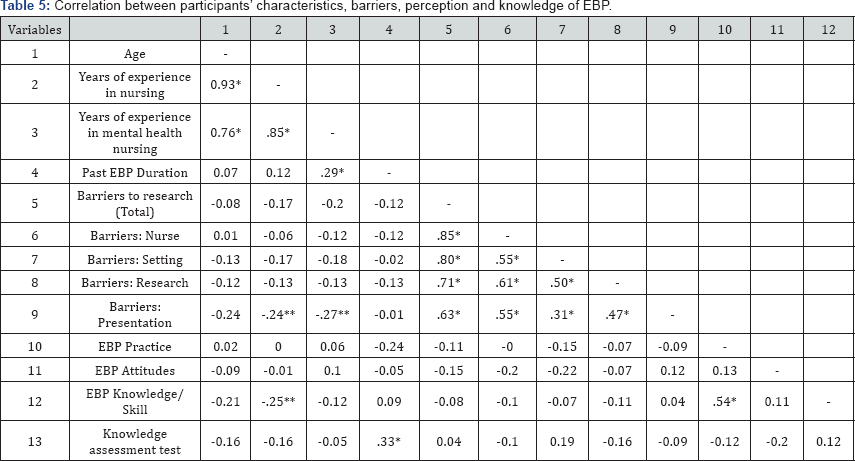

The relationship between the participants' characteristics (age, years ofexperience in nursingand mental healthnursing) and the instruments (Barriers to Research Utilization Scale, Evidence Based Practice Questionnaire, and Knowledge Assessment Test) were investigated using Pearson product-moment correlation. Among participants' characteristics, there was a strong positive correlation with years of experience in nursing, r(66)=0.93, p<0.001, and with years of experience in mental health nursing, r(66)= 0.76, p <0.001 (Table 4). Naturally, years of experience in nursing was positively correlated with years of experience in mental health nursing, r(66)=0.85, p<0.001. Past EBP duration was also positively correlated with participants' scores on the knowledge assessment test, r(66)= 0.33, p<0.001 Nurses with more experience in nursing and mental health nursing also experienced lesser barriers in accessing research materials to implement the evidence into practice, r(66)=-0.25, p<0.05 and r(66)=-0.27, p<0.05 respectively (Table 5).

Independent samples t –test: Gender, past EBP involvement against participants’ barriers, perception and knowledge of EBP

Note: *p≤ .001; **p≤ .05.

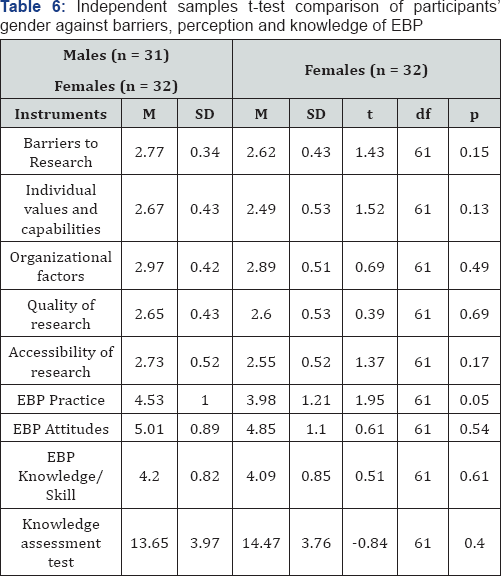

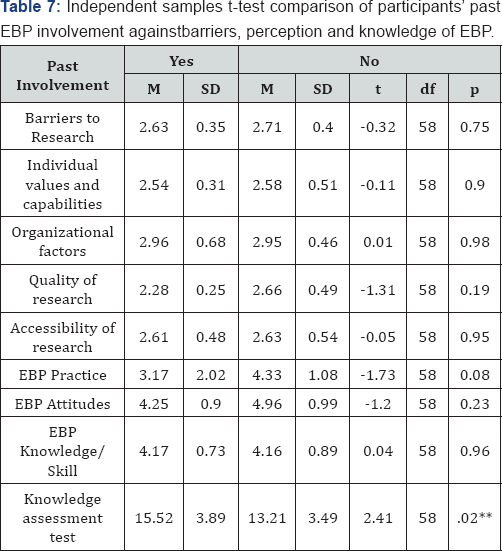

Independent samples t-tests was also conducted to compare gender and past EBP involvement with participants’ responses to the instruments. Independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare gender, past research and EBP involvement with the questionnaires (Barriers to Research Utilization Scale, Evidence Based Practice Questionnaire, and Knowledge Assessment Test). As shown in Table 5 and 6, no significant differences were found, except for knowledge assessment test and past EBP involvement, t(58)=2.41, p=0.02. Participants with prior EBP involvement had better EBP knowledge than nurses without, mean score 15.52 VS 13.21.

One-way ANOVA: Race, religion, education, marital status against participants' barriers, perception and knowledge of EBP

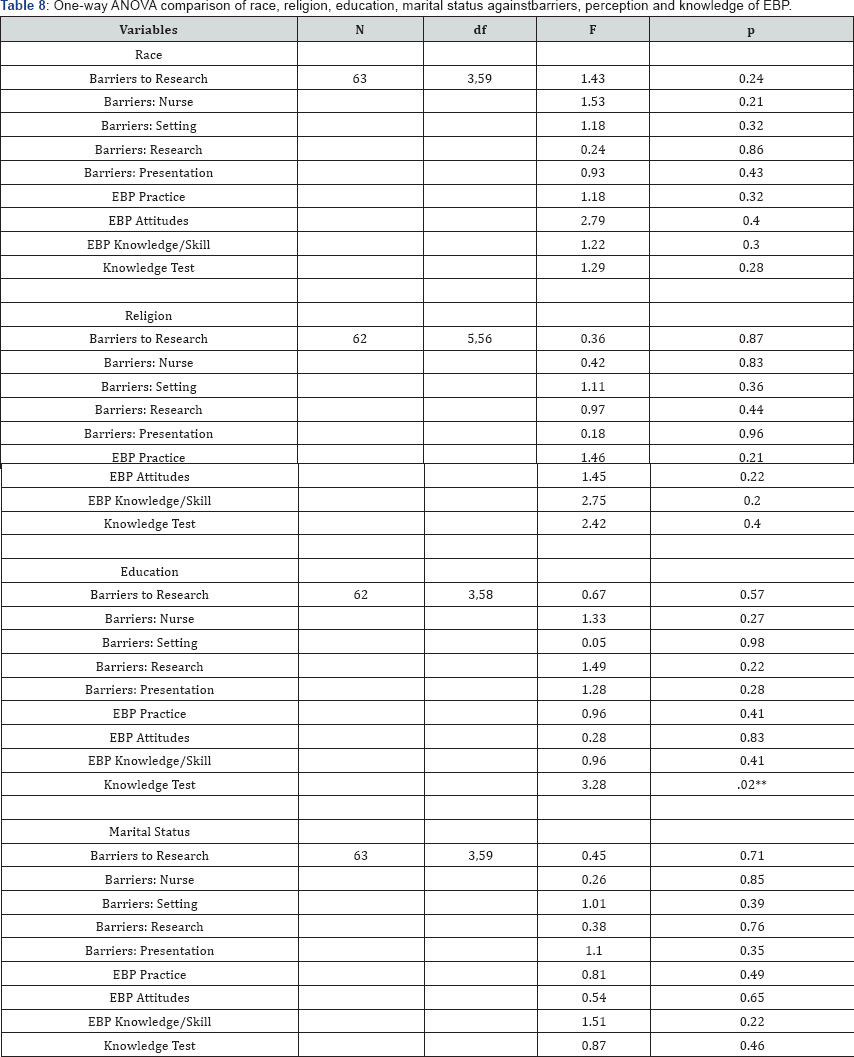

There was a statistical significant difference of educational qualification on the measure of knowledge assessment test, F(3,58)=3.28, p=0.02, ŋ2=0.15 (Table 6). Post-hoc comparison using Tukey HSD test indicated statistical significant difference in the mean score of the knowledge assessment test between the ‘degree’ (M = 15.15, SD = 3.87) and ‘diploma’ (M = 12.00, SD = 2.806) group. The ‘O level’ (M=12.00, SD=5.00) and ‘other’ (14.67, SD=4.04) group did not differ significantly from the rest.

Note: p = 2-tailed

Discussion

This study reveals that a major percentage of nurses working in public health institution in Singapore is interested in EBP. However, their average involvement were less than a month, which is too short a duration for any formal EBP project which typically involved an entire process from identification of clinical problems to stakeholders engagement. Dwelling further into the potential barriers, the mean score for the subscales of the Barriers to Research Utilization Scale were observed to be higher than previously reported studies [13,14]. Specifically, the score were>2.50, suggesting that participants perceived barriers to research to a moderate extent (maximum score of 3 suggests greatest barriers) (Table 7).

Note: *p≤ .001; **p≤ .05

This study also provided the opportunity to triangulate nurses' perception of EBP with their objective scores on the knowledge test. Though they perceived EBP moderately positive, they scored relatively low on KAT, suggesting lack in EBP knowledge. KAT scores were affected by prior EBP involvement and educational level. Furthermore, the result showed that nurses with a higher educational level performed better in the knowledge assessment test. This was congruent with Bonner et al. [15] study that nurses who had completed a university subject on nursing research had better knowledge of research and EBP [15]. Nurses who possess a degree certificate and have longer working experience in nursing were also more favorable disposed to the utilization of EBP. This is in agreement with the findings of Griffith [16], who submitted that limited practical knowledge and experience adversely affect the implementation of EBP by newly employed nurses. Moreover, barriers to adopting EBP may include suboptimal knowledge and understanding of search engines and academic terms used in research articles which can be more prevalent in nurses with lowered education level as mentioned by O'Connor and Pettigrew [17] (Table 8).

With the findings indicating that participants perceived EBP favorably and reported minimal barriers to research utilization, yet lacking knowledge in EBP, there is potential for development of a learning platform to develop nurses’ knowledge of EBP. Future research could focus on the impact of educational programs on changes in nurses' perception of EBP and triangulate that with their knowledge and involvement in EBP [18-26].

Conclusion

Delivery of quality nursing care to patients depends greatly on the ability of nursing professionals to update their knowledge and to adopt up to date evidence based therapies in the delivery of their duties. Healthcare is a very dynamic field with new evidence uncovered every day. The capacity of nurses to move with these changes will have great impact on the quality and safety of healthcare delivered. In agreement with the fundamental guidelines of nursing, new information has to be absorbed and implemented in health care delivery. Involvement in EBP enables the utilization of evidence in delivery care. Findings provide an understanding of nurse’s barriers, perception, knowledge and involvement in EBP, providing valuable information to the knowledge base on nurses' view of EBP.

References

- DiCenso A, Guyatt G, Ciliska D (2005) Evidence-based nursing: a guide to clinical practice. St Louis, Mosby, pp. 1-640.

- Drake RE, Goldman HH, Leff HS, Lehman AF, Dixon L, et al. (2001) Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health settings. Psychiatr Serv 52(2): 179-182.?

- Patel KK, Butler B, Wells KB (2006) What is necessary to transform the quality of mental health care. Health Affairs 25(3): 681-693.

- Majid S, Foo S, Luyt B, Zhang X, Theng YL, et al. (2011) Adopting evidence-based practice in clinical decision making: nurses' perceptions, knowledge, and barriers. J Med Libr Assoc 99(3): 229236.

- Funk SG, Tornquist EM, Champagne MT (1995) Barriers and facilitators of research utilization: An integrative review. Nurs Clin North Am 30(3): 395-407.

- Alspach G (2006) Nurses' use and understanding of evidence based practice: Some preliminary evidence. Criti Care Nurse 26(6): 11-12.

- Pek E, Subramanian M, Vaingankar J, Chan YH, Mahendran R (2008) Mental health professionals perceived barriers and benefits, and personal concerns in relation to psychiatric research, Ann Acad Med Singapore 37(9): 738-744.

- Loyd G (2008) EBP Readings: Nursing theory research handout. East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, USA.

- Taylor S, Allen D (2007) Visions of evidence-based nursing practice. Nurse Researcher 15(1): 78-83.

- Salmond SW (2007) Advancing evidence-based practice: A Primer. Orthop Nurs 26(2): 114-123.

- Funk SG, Champagne MT, Wiese RA, Tornquist EM (1991) Barriers: The barriers to research utilization scale. Appl Nurs Res 4(1): 39-45.

- Upton D, Upton P (2006) Development of an evidence-based practice questionnaire for nurses. J Adva Nurs 54(4): 454-458.

- Bostrom AM, Kajermo KN, Nordstrom G, Wallin L (2008) Barriers to research utilization and research use among registered nurses working in the care of older people: Does the BARRIERS Scale discriminate between research users and non-research users on perceptions of barriers? Implementat Sci 24: 3.

- Upton D, Upton P (2006) Development of an evidence-based practice questionnaire for nurses. J Adv Nurs 53(4): 454-458.

- Bonner A, Sando J (2008) Examine the knowledge, attitudes and use of research by nurses. J Nurs manag 16(3): 334-343.

- . Griffiths JM, Closs SJ, Bryar RM, Hostick T, Kelly S, et al. (2001) Barriers to research implementation by community nurses. British Journal of Community Nursing 6(10): 501-510.

- Munroe D, Duffy P, Fisher C (2008) Nursing knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to evidence-based practice: before and after organizational supports. Medsurg Nurs 17(1): 55-60.

- O'Connor S, Pettigrew CM (2009) The barriers perceived to prevent the successful implementation of evidence-based practice by speech and language therapists. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 44(6): 1018-1035.

- Barnsteiner J, Prevost S (2002) How to implement evidence-based practice. Reflections on Nursing Leadership/Sigma Theta Tau International. Honor Society of Nursing 28(2): 8-21.

- Brown CE, Ecoff L, Kim SC, Wickline MA, Rose B, et al. (2009) Multi- institutional study of barriers to research utilisation and evidence- based practice among hospital nurses. J Clin Nurs 19(13-14): 19441951.

- Celeste RR, Kiehl E (2009) Applying the Settler model of research utilization in staff development: revitalizing a preceptor program. Journal for nurses in staff development 25(6): 278-284.

- Clement JN, Trompeter JM (2011) An innovative format of journal club among pharmacy practice residents. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning 3(4): 327-332.

- Dans AL, Dans LF, Silvestre MAA (2008) Painless evidence based medicine. West Sussex, John Wiley & Sons, UK, pp. 1-160.

- Adelaine (2011) Joanna Briggs Institute and University of Adelaide. Reviewers’ manual. Joanna Briggs Institute and University of Adelaide, Australia.

- Sackett D, Straus ES, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes BR (2000) Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM, (2nd edn), Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, UK.

- Tsai SL (2003) The effects of a research utilization in-service program on nurses. Int J of Nurs Stud 40(2): 105-113.