Gender Similarities in Work Experiences, Satisfactions and Well-Being among Physicians in Turkey: One More Time1

Ronald J Burke1*, Mustafa Koyuncu2, Jacob Wolpin1, Sevket Yirik3, Kadife Koyuncu2 and Gulseren Yurcu3

1Department of Organizational Studies, York University, Canada

2Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Turkey

3Akdeniz University, Turkey

Submission: July 07, 2017; Published: August 21, 2017

*Corresponding author: Ronald J Burke, Department of Organizational Studies, York University, Canada, Email: rburke@schulich.yorku.ca

How to cite this article: Ronald J B, Mustafa K, Jacob W, Sevket Y, Kadife K, Gulseren Y. Gender Similarities in Work Experiences, Satisfactions and Well-Being among Physicians in Turkey: One More Time1. JOJ Nurse Health Care. 2017; 3(4): 555618. DOI: 10.19080/JOJNHC.2017.03.555618

Abstract

Turkey, similar to most countries, has various ways of delivering health care to its citizens. It relies on doctors and nurses to provide high quality care. Turkey has a shortage of physicians compared to other neighboring countries and spends less money in its health care delivery than they do. Interestingly more women are becoming physicians, with about twenty-five percent of Turkish physicians being women. Encouraging more women to become physicians and retaining current women physicians seems to be important in maintaining the quality of care. In addition, understanding work and family experiences of female physicians as well as their male colleagues, would seem to be helpful in this regard. The present study considers potential differences in a variety of outcomes, replicating earlier work. Data were collected from 310 physicians using anonymously completed questionnaires in early 2016. Measures included personal demographic and work situation characteristics (e.g., age, years in the profession, levels of optimism), work experiences (levels of psychological empowerment and work engagement), work outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction, hospital affective commitment, intent to quit), and well-being (e.g., burnout).

Introduction

Healthcare is an important element in the quality of life of countries citizens. National governments support health care systems, with countries pursing different policies and approaches to its delivery. Doctors and nurses are central to the hands on delivery of health Turkey has fewer physicians per capita than neighboring countries. Thus retaining currently physicians and attracting new physicians to turkey, or interesting more women and men to become physicians is a national priority. Although the majority of physicians in Turkey are male, females continue to enter the profession. Females comprise between twenty and twenty-five percent of physicians in Turkey, though they likely work in different areas of practice.

Some research has focused on gender differences in the experiences of female and male physicians. Here is a sample of this research undertaken in Turkey. Ozale et al. [1] found no differences in nutrition knowledge among 137 male and 73 female physicians in Ankara working in various hospitals, both groups having relatively low levels of nutrition knowledge. Sarp et al. [2] studied stress levels among physicians from three large hospitals in Ankara (n=699) and found no gender differences in stress sources and levels. Uncu et al. [3], based on 113 female and 83 male physicians, studied job-related affective response and found no gender differences in stress, anxiety and depression. Finally, Ozyrut et al. [4] examined job dissatisfaction and burnout and found no differences in either in a study of 598 physicians working in various hospitals in Burke et al. [5] compared the work experiences, satisfactions and well-being of 237 male and 194 female physicians in Turkey. They were first compared on here demographic factors (e.g., age, marital status, parental status) and eight work situation characteristics (e.g., hospital size, type of practice, income, city size). Few gender differences were present: male physicians had longer professional tenure, worked more hours and extra-hours per week. Female and male physicians were similar on stable individual difference factors (e.g., Type A behavior, optimism, proactive personality, and work a holism), job behaviors, (perfectionism,), work outcomes (job satisfaction, work engagement, intent to quit) and psychological well-being (e.g., friends and family satisfactions. Female physicians reported less career satisfaction and a tendency to be absent more, higher levels of work-family conflict, and more psychosomatic symptoms. They concluded, in line with these and earlier published findings, that few significant gender differences were present but then they appeared they disadvantaged female physicians. Other research has found that female physicians perform more successfully with some types of patients, particularly children, women, some types of illnesses (e.g., asthma, sexual issues).

There are some common features in research on physicians. First, physicians work long hours having heavy workloads. Second physicians complain about their working long hours and heavy workloads. Third, physicians would prefer to have less heavy workloads and work fewer hours. Fourth, the long work hours and heavy workloads of physicians have negative effects on physician well-being and patient satisfaction. There are also inconsistent findings with some researchers finding few if any gender differences [6-9] while others find some differences [10,11].

The present study of a large sample of male and female Turkish physicians examined personal demographic and work situation characteristics, including a measure of personality- optimism, and work-family and family work conflict, as predictors of various work outcomes. These included job satisfaction, hospital affective commitment, work engagement, burnout and intent to quit or change jobs. It attempts to replicate our earlier Turkish study [12] data being collected eight years later.

Method

Procedure

Data were collected from physicians working in twelve hospitals in Antalya Turkey using anonymously completed questionnaires. Physicians worked in both public and private hospitals. A total of 2050 physicians worked in these hospitals, 1566 in public and 184 in private hospitals. Data were collected in January through March 2016. A total of 700 physicians were randomly selected to participate. Three hundred and ten completed questionnaires were received, a 44% response rate. Surveys were translated from English into Turkish and back using the back translation method, by members of the research team fluent in both languages.

Respondents

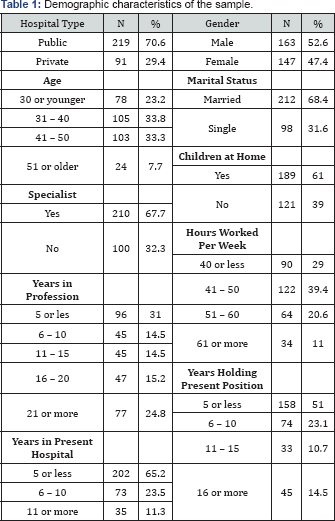

Table 1 presents the personal demographics and work situation characteristics of the 310 participating physicians. These characteristics were measured by single items. The sample contained slightly more males than females (53% males). Most were married (685), had children (61%), the bulk being between 31 and 50 years of age (67%). Most worked in public hospitals (71%), were specialists (68%), had practiced for 5 years of less (31%), had held their present positions for 5 years or less (51%), had worked in their present hospitals for 5 years or less (65%), and most worked 41-50 hours per week (39%). There was considerable range across each measure however.

Measures

All measures used in this research have been used previously and shown to have desirable psychometric properties.

Personal demographic and work situation characteristics

The single items are shown in Table 1. In addition, the personal characteristic of optimism was also included in the study. Optimism was measured by an eight item scale (α=.95) developed by Scheier et al. [13]. Responses were made on a five Point-Likert scale of agreement. An item was "In uncertain times, I usually expect the best."

Work and family outcomes

Seven work and family outcomes were assessed by multiple item measures.

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction was measured by a seven item scale (α=88.) created and validated by Taylor & Bowers [14]. Physicians made their responses on a five point Likert scale of agreement. An item was "All in all how satisfied are you with the persons in your work group?"

Psychological empowerment

Psychological or personal feelings of empowerment were assessed by a twelve item measure created by Spreitzer [15]. It assessed four dimensions, each addressed by three items. Responses were made of a seven point Likert scale of agreement. The dimensions were: Meaning (α=.86) "The work that I do is meaningful to me."; Competence (α=.92)" I am confident about my ability to do my job'; Self-determination (α=.92.) "I have significant autonomy in determining how to do my job." and Impact (α=.96) "My impact on what happens in my unit is large." A composite measure of feelings of psychological empowerment was developed (α=.94) as the four dimensions were all significantly and positively inter-correlated, the mean inter-correlation being .62, p<.001.

Hospital affective commitment was assessed by a six item measure (α=.94) created and validated and Allen (19997) Physicians indicted their agreement on a five point Likert scale. An item was "I am proud to tell others I work at my hospital."

Intent to quit was assessed by two items (α=.77) developed by Burke (1991). One item was "Are you currently looking for a different job in a different organization?" (yes/No).

Work engagement

Three dimensions of work engagement were assessed using scales developed by Schaufeli et al. [16] Physicians reported their agreement with each item on a five-point agreement scale. Vigor was measured by six items (α=.82); one item being "At my work I feel bursting with energy." Dedication was assessed by five items (α=81.); an item being" I am proud of the work that I do". Absorption was assessed by six items (α=.65); one item being "I am immersed in my work." A Composite measure of work engagement was developed (α=.93) combining the three dimensions as they were all significantly and positively intercorrelated, the mean inter-correlation being .72, (p<.001).

Work-family conflict and Family-work conflict were each assessed by five item scales developed by Carlson et al. [17]. Reliabilities of the Work-family conflict scale and the Family- work conflict scale were .95 and .78 respectively. Physicians responded on a five point Likert scale of agreement. An item on the Work-family conflict scale was "The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life." One item on the Family- work conflict scale was "I have to put off doing things at work because of demands of my time at home." These two conflict scales were significantly and positively correlated, r-=.73, p<.001.

Burnout

Three dimensions of burnout were measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory [18] Physicians indicated how often they experienced each item on a seven-point frequency scale. Exhaustion was assessed by five items (α=.92). One item was "I feel burned out from my work."Cynicism was measured by five items (α=.76). An item was "I have become more cynical about whether my work contributes anything." Finally, Personal efficacy was measured by six items (Y=.85). One item was "I have accomplished many worthwhile tings in this job. These items were reverse coded to conform to the other two dimensions. A composite measure of burnout was developed (α=.86) since all three dimensions were positively and significantly inter-correlated, the mean inter-correlation being .31, p<.001.

Results

Personal and work situation characteristics

Table 2 shows the comparisons of female and male physicians on ten personal and work situation characteristics. Only one significant gender difference was present; females reported significantly lower levels of optimism than did their male colleagues. There was also a tendency for fewer females to possess specialist designations (p<.10).

Work and well-being outcomes

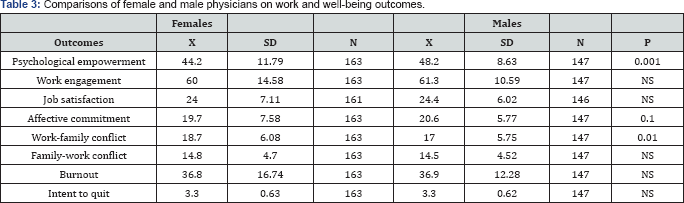

Table 3 presents the comparisons of female and male physicians on eight work and well-being outcomes. Two differences were statistically significant; women reporting significantly higher levels of work family conflict, and lower levels of psychological empowerment. There was also a tendency for females to indicate lower levels of hospital affective commitment (p<.10) Females and males were similar on job satisfaction, work engagement, levels of burnout, and intent to quit (the latter being low for both females and males. In addition, both females and males reported generally favorable responses on these measures.

Discussion

Our findings were consistent with our earlier work as well as the research of others [19]. In noting similarities in the personal and work situation characteristics and work experiences and outcomes of female and male physicians. Thus characteristics (Table 2) l and generally similar on work and females and males were similar on personal and work situation well-being outcomes (Table 3).

The areas of significant differences were also understandable. Female physicians reported more work-family conflict and burnout and lower levels of psychological empowerment. The first two areas likely represent the greater responsibilities female physicians shoulder for family and home responsibilities. The latter captures findings that indicate female physicians are less likely to be involved in major decision making roles in their hospitals than are male physicians.

Practical implications

Given the shortage of physicians in Turkey, encouraging women physicians from other countries to come to Turkey, given the lack of gender differences might be a strong selling feature. In addition, these data, and others [20] could be used with girls in high schools and universities to consider medical practice as a career.

Hospitals however also have active roles to play as well. Female physicians reported less psychological empowerment, less career development opportunities, less organizational participation and then and fewer personal and interpersonal relationships did their male colleagues. Akansel et al. [21] found that female physicians had less involvement in high level decision making than did their male counterparts. Increasing the role played by female physicians in hospital governance, decision making and priority setting would be a useful initiative. Finally, although our study did not examine sexual harassment, bias and discrimination, this likely to be a more serious concern for females than male physicians. Female physicians experienced more work-family conflict than their male colleagues. Fortunately, considerable understanding of ways to reduce work-family and family work-conflict has taken place over the past decade. Successful initiatives have included.

Future research directions

It would be informative to replicate the present study using a larger and more representative sample of female and male physicians in Turkey. Women physicians were overrepresented in the present study. Including indicators of job behavior, fatigue, and for women physicians, indicators of perceived bias would be informative. Finally, including measures of physician health such as anxiety depression and family and life satisfaction would offer a more comprehensive picture of both satisfactions and concerns of female and male physicians.

Limitations of the study

All research has limitations and this study is no exception. Although the sample of female and male physicians is relatively large it is not clear it is representative of physicians in Turkey. There are more females represented here than in the physician group in Turkey as a whole. In addition, all data were collected from a small number of hospitals in one region of turkey so the extent to which findings generalize to other parts of Turkey or to other countries is indeterminate. All data were collected using self-report questionnaires raising the possibility of response set tendencies.

Acknowledgement

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by York University, Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University and Akdeniz University. We thank the hospitals for their participation and our respondents for their contribution.

1Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by York University, Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University and Akdeniz University. We thank the hospitals for their participation and our respondents for their contribution.

References

- Ozcelik AO, Surucuoglyu MS, Akan LS (2007) Survey of nutrition knowledge levels of Turkish physicians: Ankara as a sample. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 6(6): 538-542.

- Sarp N, Yarpuzlu AA, Onder OR (2005) A comparative study of organizational stresses in there hospitals in Ankara, Turkey. Stress and Health 21(3): 193-197.

- Uncu Y, Bayram N, Bilgel N (2007) Job-related affective wellbeing among primary health care physicians. Eur J Public Health 17(5): 514-519.

- Ozyurt A, Hayran O, Sur H (2006) Predictors of burnout and job satisfaction among Turkish Physicians. QJM 99(3): 161-169.

- Burke RJ, Koyuncu M, Fiksenbaum L (2009) Gender differences in work experiences, satisfaction and wellbeing among physicians in Turkey. Gender in Management: An International Journal 24(2): 70-91.

- Kisa S, Kisa A, Younis MZ (2009) A discussion of job dissatisfaction and burnout among public hospital physicians. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education 47(4): 104-111.

- Foss I, Nubling M, Hasselhorn HM, Schwappach D, Rieger MA, et al. (2008) Working conditions and work-family conflict in German hospital physicians: Psychosocial and organizational predictors and consequences. BMC Public Health 8: 353-379.

- Efeoglu IE, Ozcan S (2013) Work-family conflict and its association with job performance and family satisfaction among physicians. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Science 7(7): 43-48.

- Ozyurt A, Hayran O, Sur H (2006) Predictors of burnout and job satisfaction among turkish physicians. Quantitative Journal of Medicine 99: 1761-169.

- Anfarta N (2011) The relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction: A structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. International Journal of Business and Management 6(4): 168-177.

- Wang Y, Liu L, Wang J, Wang L (2012) Work-family conflict and burnout among Chinese doctors: The mediating role of psychological capital. J Occup Health 54(3): 232-240.

- Burke RJ, Koyuncu M, Fiksenbaum L (2009) Gender differences in work experiences, satisfaction and wellbeing among physicians in Turkey. Gender in Management: An International Journal 24(2): 70-91.

- Scheier MF, Carver CS (1985) Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology 4(3): 219-247.

- Taylor JC, Bowers D (1972) Survey of organizations: A machine-scored standardized questionnaire instrument. Ann Arbor, MI�x003E;l Institute for Social Research.

- Spreitzer GM (1995) Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal 38(5): 1442-1465.

- Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, Gonzalez-Roma V, Bakker AB (2002) The measurement of engagement and burnout: A confirmative analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies 3(1): 71-92.

- Carlson DS, Kacmar M, Williams LJ (2000) Construction and validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior 56(2): 249-276.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP (1996) The Maslach Burnout Inventory (3ri edn), Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo alto, USA.

- Aycan Z (2004) Key success factors for women in management in Turkey. Applied Psychology: An International Review 53(3): 453-477.

- Burke RJ, Koyuncu M, Fiksenbaum L (2009) Gender differences in work experiences, satisfaction and wellbeing among physicians in Turkey. Gender in Management: An International Journal 24(2): 70-91.

- Akansel N, Ozkaya G, Ercan I, Alper Z (2011) Job satisfactions of nurses and physicians working in the same health care facility in Turkey. International Journal of Caring Sciences 4(3): 133-143.