Causal Structure Relating to the Disparity of Primary Nursing Care by Prefecture in Japan

Tanji Hoshi1*, Sugako Kurimori2, Naoko Nakayama3, Miki Kubo4 and Naoko Sakurai5

1Tokyo Metropolitan University, Japan

2Seitoku University, Japan

3St Luke's International University, Japan

4International University of Health and Welfare, Japan

5Jikei University School of Medicine, Japan

Submission: July 17, 2017; Published: August 17, 2017

How to cite this article: Tanji H, Sugako K, Naoko N, Miki K, Naoko S. Causal Structure Relating to the Disparity of Primary Nursing Care by Prefecture in Japan. JOJ Nurse Health Care. 2017; 3(2): 555608. DOI: 10.19080/JOJNHC.2017.03.555608

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to explore the causal structure of the relevant factors affecting the proportion of insurance and primary nursing care per prefecture; to clarify the overall relation, including the indirect effects as well as the direct effects, and to obtain the basic data for policies aimed at reducing the regional disparity of long-term nursing care authorization and long-term care insurance.

Method: 8 factors considered to be related to the proportion of primary nursing care and long-term care insurance were analysed. These were taken from indexes for medical facilities, elderly care institutions, healthcare manpower plus economic indicators over the last five years. An exploratory factor analysis conducted by Promaxoblique rotation using the maximum likelihood method was performed on these factors, extracted factors were referenced and latent variables were set. Covariance structure was analysed on the basis of a hypothetical model thought to define the latent variables related to the proportion of primary nursing care and long-term care insurance charges, and a model with a high degree of explanatory power was selected.

Results: The rate of primary nursing care requirement authorization and long-term care insurance charges over 5 years was named as the 'primary nursing care situation', the variables associated with the number of beds in hospitals and clinics plus the rate of utilization of such beds as 'medical facilities and institutions', the variables associated with the number of nursing home residents and the number of doctors as 'manpower and special nursing facilities', and the variables associated with the employment rate of elderly people and the mortality rate in their own homes were named the 'living conditions of the elderly'. These four latent variables were combined into a number of models, and the model with the highest explanatory power was selected. It was shown that the overall effect of 'medical facilities and institutions’ to the 'primary nursing care situation’ is 0.82, with a causal effect increasing 'primary nursing care situation’ in regions with an abundance of medical facilities. On the other hand, the overall effect of 'living conditions of the elderly’ upon the 'primary nursing care situation', i.e. the combination of direct and indirect effects, was shown to be -0.57, and a possibility of reducing the 'primary nursing care situation’ was indicated in areas where a high rate of elderly employment exists alongside a high rate of home mortality. A possibility was shown that if it is assumed to a degree of 100% that 'medical facilities and institutions’ causes an increase in the 'primary nursing care situation’, then 'living conditions of the elderly’ may have a deterrence rate towards the 'primary nursing care situation’ of approximately 70% (-0.57/0.82=69.5%). As a covariance structure analysis for 'manpower and special nursing facilities’ did not obtain a high rating for goodness of fit, it was not adopted for the model.

Conclusion: The possibility was suggested that a high number of beds required in hospitals and medical clinics along with a high rate of bed utilization may cause a rise in the rate of primary nursing care authorization and in the cost of long-term care insurance over the next 5 years.

Keywords: Rate of primary nursing care authorization; Cost of long-term care insurance; Regional disparity; Elderly employment rate; Number of hospital beds; Causal structure

Introduction

In Japan, a long-term care insurance system has been in effect since 2000, with nursing services being steadily established in each region. However, a disparity has arisen between regions in terms of the ratio of primary nursing care available. Until now, much of the research on the regional discrepancies in regards to medical treatment has focused on the cost of medical care for the elderly [1-3]. In addition, reports claiming the existence of regional disparity in measures towards the welfare of the elderly [4], plus in research relating to regional disparity in terms of the health and life expectancy of elderly people it has been reported that because the required care period tends to be longer for women than men, the nursing of women is becoming a particularly urgent need [5-7].

In April 2006 the new nursing care insurance system was devised to prevent the reduction and deterioration of the condition of primary nursing care in the municipalities, by providing preventative benefits to those most in need of support, specifically the elderly, such that general care specific to the elderly should not become necessary, and thus achieving a shift to a prevention-orientated system [8]. In order to achieve the prevention of long-term care, the importance of encouraging the maintenance of life function amongst the elderly (who make up a significant proportion of the population in each area), and of prevention of geriatric syndrome (age-related weakness, falls, cognitive impairment and malnutrition) through early detection and support have been reported [9].

Through preventative care elderly people are able to maintain their independence, and since it is necessary to take advantage of efficient use of medical expenses and the cost of long-term care, the degree of independence amongst elderly people has also played a role in economic evaluations. Yoshida et al. [9] suggested the possibility, on the basis that a decline in independence results in a drastic increase in the cost of medical and long-term nursing care, that maintenance of independence and postponement of serious illness are tied up with the reduction of medical and nursing costs for the elderly. As the population continues to age, limiting the increase in primary caregivers as much as possible and stabilizing the cost of longterm care insurance are not merely financial concerns; the issue should also be emphasized from a point of view taking into account the QOL (Quality of Life) for elderly people.

Nevertheless, despite an observed disparity of approximately two times at the prefectural level in terms of the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of long-term care insurance between regions, previous comprehensive research of the main factors related to the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of long-term care insurance is not found outside of the authors' report [10]

Against this background, the objectives of this study are to explore the factors relevant to the rate of primary nursing care and the cost of long-term care insurance on a prefectural basis, to construct a conceptual model, to clarify the overall relationship accounting for both direct and indirect factors, and to ultimately obtain the basic data for policies aimed at reducing the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of long-term care insurance.

Research Methods

Selection of relevant factors and collection of data

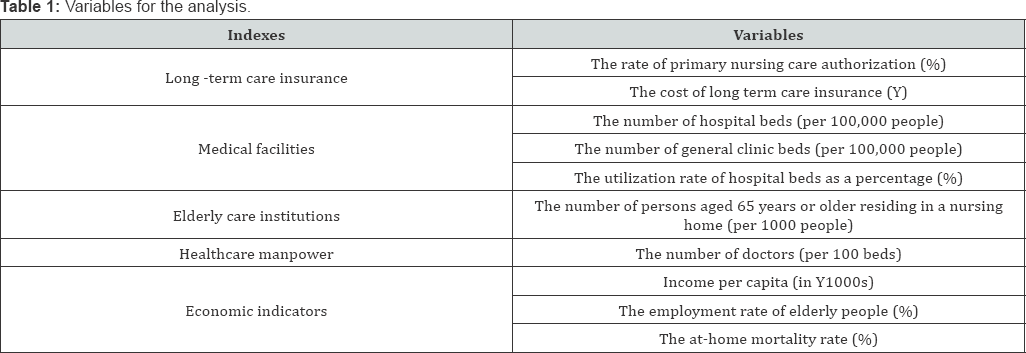

For the factors considered to be associated with the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of long-term care insurance, a selection of indexes for medical facilities, elderly care institutions, healthcare manpower and economic indicators on the basis of being significantly associated with the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of long-term care insurance, plus factors not regarded as being significantly related but showing a negative association, made up a total of 8 primary factors used for the analysis.

The 8 selected factors consisted of the following: the medical facilities index as indicated by the number of hospital beds per 100,000 people (hereafter, number of hospital beds), the number of general clinic beds per 100,000 people (number of clinic beds) and the utilization rate of hospital beds as a percentage (sickbed utilization rate), the elderly care institutions index as indicated by the number of persons aged 65 years or older residing in a nursing home per 1000 people (nursing home residency), the healthcare manpower index as indicated by the number of doctors per 100 beds (number of physicians), an economic indicator consisting of income per capita (in ¥1000s) on a prefectural basis (prefectural income), the employment rate of elderly people (%) (elderly employment rate); and the at-home mortality rate (%).

The rate of primary nursing care authorization was insured under level 1 of the 5 level primary nursing care system calculated using the number of authorized persons in a census organized by nursing care level, gender, age rank, and prefecture of long-term care benefits, those people institutionalized/ [11], and dividing by the population for each age group using population by prefecture, age group (5 age classes) and gender - total population [12]. For the cost of long-term care insurance, the base amount of insurance for each nationwide insurer as well as the base benefit amount per insured person was used [13]. For the number of hospital beds, the number of clinic beds, the sickbed utilization rate and the number of physicians, the Medical Facilities Research Report [14] was used, and for nursing home residency, the 2002 prefectural statistics [15] were used. For prefectural income, the prefectural economic calculation made by the Economic and Social Research Institute, Cabinet Office [16] was used, for the elderly employment rate, the Employment Status Survey [17] was used, and for the at- home mortality rate, Table 1 of major statistics within the Vital Statistics Annual Report [18] was used. The list of variables is shown in Table 1.

Analysis Method

For the analysis, the 8 selected factors considered relevant to the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of long-term care insurance were subject to an exploratory factor analysis with Promax oblique rotation, using the maximum likelihood method. The latent variables were set with reference to the extracted factors, a covariance structure analysis was performed on the basis of a hypothetical model that was considered to be related to the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of long-term care insurance, and a model with a high degree of explanatory power was adopted. SPSS 12.0 J for Windows and Amos 5.0 for Windows were used as the analysis software. AGFI, NFI and RMSEA were used to test the conformation of the model.

Results

Association between each indicator

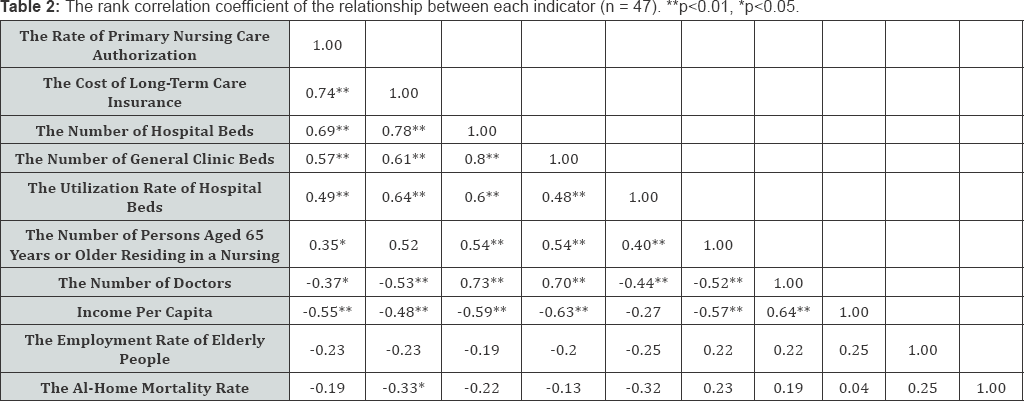

The relationship between each indicator was analyzed using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (Table 2). The rate of primary nursing care authorization was shown to have a significant positive correlation with the cost of long-term care insurance, the number of hospital beds, the number of clinic beds, the sickbed utilization rate and nursing home residency, and a significant negative correlation with prefectural income and the number of physicians. The cost of long-term care insurance was shown to have a positive correlation with the number of hospital beds, the number of clinic beds, the sickbed utilization rate and nursing home residency, and a negative correlation with prefectural income, the number of physicians and the at-home mortality rate.

Descriptive statistics for each indicator

The descriptive statistics for each variable are shown in Table 3. It can be seen that the disparity between prefectures is 1.7 times for the rate of primary nursing care authorization and 1.8 times for the cost of long-term care insurance. Similarly, the results show disparities of 2.8 times for the number of hospital beds, 8.8 times for the number of clinic beds, 1.1 times for the sickbed utilization rate, 7.3 times for nursing home residency, 2.2 times for the number of physicians, 2.1 times for prefectural income, 1.7 times for the elderly employment rate and 3.5 times for the at-home mortality rate.

For the 10 indexes utilized there were no particularly prevalent outliers other than the number of doctors and the prefectural income of the Tokyo Metropolitan area, and the skewness distribution was relatively stable, so they were analysed without transformation (Table 3).

Naming and configuration of latent variables

As the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of long-term care insurance had a correlation coefficient of 0.74 and a strong positive correlation, indicating a similar trend between the two, these were grouped together into a variable named the 'primary nursing care situation'.

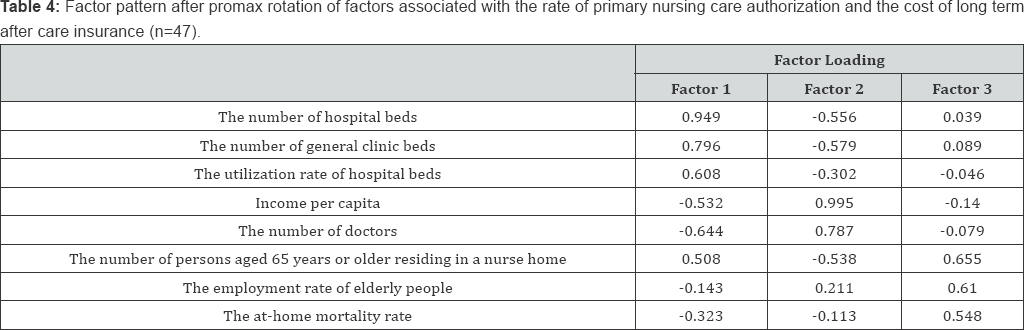

As a result of factor analysis, Factor 1 was identified as a variable that may be interpreted as a function of medical facilities was named 'medical facilities and institutions', Factor 2 was identified as a variable that may express the economic health of a region on the basis of having a large number of doctors and a high average income and was named the 'wealth status', while Factor 3 was identified as a variable that can be interpreted as the circumstances and environment deeply connected to the lifestyle of elderly people, and was named 'circumstances surrounding the elderly' (Table 4). The 4 variables were combined in various ways to produce dels of multiple configurations in order to identify those with high conformity and high explanatory power.

However, through the process of creating the various models a comparative result was found suggesting that a variable consisting of the number of physicians and the nursing home residency, also strongly related to Factor 2, had a higher degree of fit to the model than did the previous variable 'wealth status’. Thus a new variable named 'manpower and special nursing facilities’ was included in the analysis (Table 4).

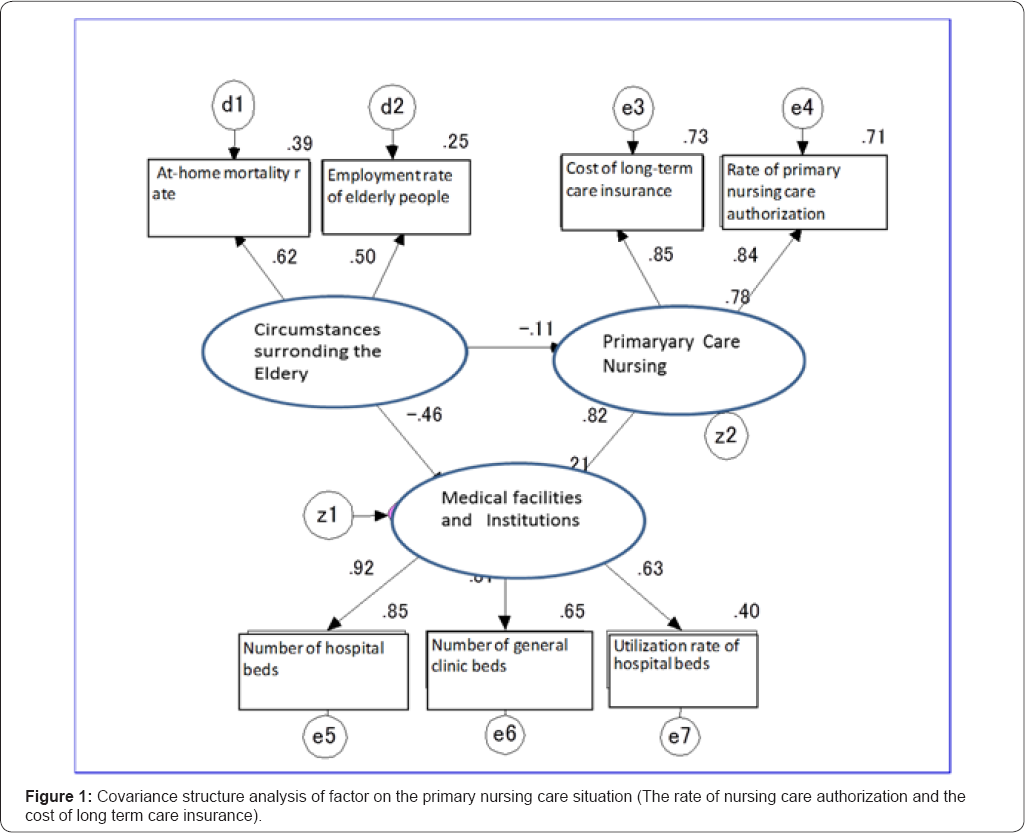

Comprehensive analysis of primary nursing care situation

The 'circumstances surrounding the elderly' showed a negative standardized estimated value against 'medical facilities and institutions’ the 'primary nursing care situation, indicating that it may have a suppressive effect on each. Additionally, a standardized estimated value of 0.82 was found for 'medical situation' facilities and institutions’ towards the 'primary nursing care situvation'(Figure 1).

The model obtained a high goodness of fit, with ratings of AGFI=0.822, NFI=0.924, RMSEA=0.033. It was revealed that the model can explain 78% of the 'circumstances surrounding the elderly' variable. Finally, as the analysis of 'manpower and special nursing facilities’ resulted in a low fitness rating, it was not included in the model.

Direct effects upon the primary nursing care situation

In terms of the direct effect of the association between each latent variable, a statistically significant positive value of 0.82 was shown from 'medical facilities and institutions' towards the 'primary nursing care situation’ while the value from 'circumstances surrounding the elderly' was a non-significant 0.11. The possibility was also suggested that the 'medical facilities and institutions’ variable, related to the number and utilization of beds in hospitals and clinics, may directly cause increases to the 'primary nursing care situation 'variable relating to the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of long-term care insurance.

Overall effects upon the primary nursing care situation

The overall effect of 'circumstances surrounding the elderly' upon the 'primary nursing care situation’, in other words the combined effect consisting of the direct effect (-0.11) and the indirect effect (0.46) was -0.57, suggesting the possibility that areas with high rates of elderly employment and at-home mortality may see a drop in the 'primary nursing care situation’. In contrast, the overall effect of 'medical facilities and institutions’ on the 'primary nursing care situation' was 0.82, indicating the possibility that the 'primary nursing care situation’ may increase in areas with many medical facilities.

Under an assumption that the 'primary nursing care situation’ is defined by 'medical features and institutions’ to a value of 100%, it is suggested that 'circumstances surrounding the elderly’ may have a deterrence effect of around 70% (-0.57/0.82=69.5%) against the 'primary nursing care situation’. For the latent variables, although a covariance structure analysis including 'manpower and special nursing facilities' was able to explain 87% of the 'primary nursing care situation’, the scores on the conformity index of AGFI=0.717, NFI=0.808 and RMSEA=0.141 did not indicate a high goodness of fit and so the variable was excluded from the model (Figure 1).

Discussion

Relation to hospitals and nursing care homes

As the rate of primary nursing care authorization by prefecture used in this study comes from a report roughly three years after the commencement of the nursing-care insurance system, the data was considered to sufficiently reflect reality nationwide. In addition, due also to the fact that a strong correlation was found between the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the monthly cost of nursing insurance, the 'primary nursing care situation’ variable was considered to reflect the true state of nursing on a prefectural basis.

Looking at the relationship between each latent variable in terms of overall effect, a statistically significant standardized estimate was obtained indicating that 'medical facilities and institutions’ increased as a direct effect of the 'primary nursing care situation’. The possibility was suggested that a higher number of sickbeds in hospitals and clinics and a higher rate of sickbed utilization could lead to an increase in the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of nursing insurance. In response to the possibility that development of the medical provision system stimulates demand [19] and that the number of caregivers could increase as a result a longterm public hospitalization, a detailed investigation into the confounding factors is required.

Although almost no direct effect of 'circumstances surrounding the elderly’ upon the 'primary nursing care situation’ was observed, a strong possibility was suggested that it may play a related role indirectly, via 'medical facilities and institutions’.

Turning to the 'manpower and special nursing facilities’ variable, although the result of the R<SEA analysis was of low fit at 0.141, the coefficient of determination for the 'primary nursing care situation’ rose to 87%.

In this study, an attempt was made to create a model based on an analysis of the government programs for medical facilities for nursing care, but a high goodness of fit was not obtained. However, as the number of nursing care facilities increases in response to Japan's aging population, a large disparity is emerging at the prefectural level. Depending on the development of nursing care facilities, demand for admission to such facilities is stimulated, and consequentially a need for more nursing care for the elderly arises; research that investigates in detail the possibility that such factors are necessitating an increase in the number of care givers has been considered to have strong implications.

Furthermore, along with investigation of disparity not only between prefectures but also in terms of disparity within prefectural secondary medical care and between municipalities, it will be necessary to further clarify the factors which determine the situation surrounding primary nursing care, by means of a follow up study focusing on individual cases.

The rate of primary nursing care authorization per prefecture used in this study was not adjusted for regional differences in age distribution. Accordingly, an age-adjusted weighted disability prevalence (WDP) by prefecture, calculated by the authors [20] using nursing insurance statistics, was analyzed as the observed variable but a high goodness-of-fit rating was not obtained.

Elderly Employment Rate and at-Home Mortality Rate

In this study, the elderly employment rate [17] was defined as the ratio of the elderly population currently working in order to generate a main source of income, to those who are currently resting.

'Circumstances surrounding the elderly’, relating to the elderly employment and at-home mortality rates, showed an overall effect of lowering the 'primary nursing care situation’. It has been suggested that, assuming the overall effect of the 'primary nursing care situation’ in regulating 'medical facilities and institutions’ to be 100%, 'circumstances surrounding the elderly’ may have a controlling power of approximately 70%. In addition, in a simple covariance structure analysis model of 'circumstances surrounding the elderly’ and the 'primary nursing care situation' an extremely high fitness rating was obtained, accounting for 56% of the 'primary nursing care situation’.

In the present study, it is suggested that the implication that a growing elderly labour force may indirectly reduce nursing care and the number of bedridden individuals indicates a need to create an environment in which it is possible for the elderly to not only earn a wage but also to feel more purposeful in life and that they are making a positive contribution to society.

Findings are already being reported which link the elderly employment rate to the rate of primary nursing care authorization. Looking at the health expectancy (average period of independence) by municipality within Shimane Prefecture, municipalities in which more men work in agriculture show a longer health expectancy. It is reported that in such an environment where people may continue to work even as they approach old age, one can continue to feel a sense of purpose, and the possibility of preventing such high levels of nursing care may arise as a result [6].

In order to rectify the disparity between prefectures in terms of the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of long-term care insurance, it is hoped that detailed research will be conducted in order to determine what kind of mechanisms might lead from a high rate of elderly employment and a high rate of income to a lowering of the rate of primary nursing care authorization. One feels that as the primary nursing care authorization system reacts to a poor level of health and the influence of social, economic and cultural factors [21,22], and against that background an upheaval in the nuclear family and the role of women in society results in a lack of home-based caregivers for the elderly, it may become common that one has no choice but to accept institutionalization into hospital care.

At-Home Mortality Rate and Other Factors

A negative correlation was found between the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the elderly at-home mortality rate. However, the at-home mortality rate continues to decrease year-on-year; disparity between prefectures in 1993 was 3.5 times but fell to 1.9 times by 2003 indicating that inequality is shrinking rapidly. It has been speculated that in regions where the trend for the at-home mortality rate to fall over time is particularly weak, that is in Tokyo, Kyoto, Kanagawa, Hiroshima, Chiba, Saitama and Aichi, home hospice care is likely to become more widespread in urban areas.

Future issues

By running a covariance structure analysis for factors determining the regional (prefectural) disparity of nursing home admissions, it was suggested that 'medical facilities and institutions’ is likely to directly contribute to the escalation of the 'primary nursing care situation’ which encompasses the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of longterm nursing insurance. However, as a cross-sectional survey, only the existence of a relationship was revealed by this study Additionally, it was not possible to find a clear relationship between prefectural income and the number of physicians (which showed a significant negative correlation with the rate of primary nursing care authorization in the rank correlation analysis) in the covariance structure analysis.

In addition to developing indicators that clearly reflect the reality of elderly employment, developing indexes to express feelings of duty, purpose in life and so on, and identifying the associations and mechanisms relating to the 'primary nursing care situation’, clarifying how having meaning in one’s life (including labor, earning a wage) might control the rate of primary nursing care authorization will be an important goal for future research. Additionally, hereafter, there is a desire to ascertain empirically through intervention studies through which kinds of mechanisms 'medical facilities and institution’ causes the 'primary nursing care situation' to increase and how 'circumstances surrounding the elderly’ controls the 'primary nursing care situation’, and also to make a scientific basis for correcting the disparity in the rate of primary nursing care authorization. In terms of support measures in such a case, it could be said that there is a need to focus not only on the regulation of sickbeds but also the circumstances surrounding the everyday life of the elderly such as guaranteeing an income and doing work which gives life purpose. Furthermore, in this study, as the rate of primary nursing care authorization by prefecture demonstrated high correlation across genders (0.89), analysis was not performed separately by gender, though as it is not possible to rule out the possibility that gender might have played a role in the correlation between factors as a confounding factor itself, future research will also involve analysis by gender.

Conclusion

It was suggested that the higher the number of beds in hospitals and clinics, and the higher the utilization rate of those beds, the higher the rate of primary nursing care authorization and the cost of nursing insurance are likely to be. Additionally, although no strong direct effect was found for 'circumstances surrounding the elderly’ upon the 'primary nursing care situation’, a strong possibility of an indirect role via 'medical facilities and institutions’ was suggested.

References

- Fujiwara Y, Hosh T (1998) Review of prefectural differentials of inpatient: medical cost for the elderly nihon koshu eisei zasshiapanese. Journal of Public Health 45(11): 10508.

- Fujiwara Y, Hoshi T, Shinkai S, Kita T (2000) Regulatory factors of medical care expenditure for older people in Japan-analysis based on secondary medical care areas in Hokkaido. Health Policy 53(1): 39-59.

- Taniguchi R, Fujiwara Y, Watanabe T, Hasegawa A, Takabayashi K, et al. (2001) The Review of Municipal Gap of the Medical Care Expenditure for the Aged in Japan. Comprehensive Urban Studies, pp. 65-76.

- Sato M, Hashimoto S (2000) Changes in prefectural and municipal differences of welfare measures for the elderly. Journal of health and welfare statistics 47(4): 8-13.

- (2008) Regional variations in health expectancy in Shimane prefecture. Shimane: Shimane Prefectural Institute of Public Health and Environmental Science, Shimane Prefectural Institute of Public Health and Environment Science, pp. 27-28.

- Itogawa K, Fujitani T, Seki R. The factor analysis influences regional disparity of the healthy life expectancy. Report of the Shimane Prefectural lnstitute of Public Health and Environmental Science 44: 70-72.

- Takeda S (2002) Necessary long-term care illness in nursing-care insurance and unqualified non-certified period (healthy life). Japanese public health magazine 49(5): 417-424.

- (2005) Shukan hoken eisei news. Shakai hoken jitumukenkyuj 1293: 17-32.

- Yoshida H, Fujiwara Y, Kumagaya O (2004) Creating a database for economic evaluation of nursing care prevention - Medical/nursing care benefit expenses by elderly independence degree. Journal of health and welfare statistics 51(5): 1-8.

- Kurimori S, Hoshi T (2007) Analysis of covariance structure of factors that regulate the difference of certification rate of nursing care required by prefecture. The Japanese Journal of Health and Medical Sociology suppl 18: 83.?

- (2003) Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey of Long-term Care Benefit Expenditures.

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Population Estimates 2002.

- http://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2003/07/s0728-5e2.html

- (2002) Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey of Medical Institutions.

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Statistical Observations of Prefectures 2002.

- (2003) Cabinet Office Government of Japan. Annual Report on Prefectural Accounts.

- (2002) Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Employment Status Survey

- (2003) Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Vital Statistics.

- Nakamura H (2006) The influence of the treatment condition on the regional difference of the certification rate of long-term nursing care. Journal of health and welfare statistics 53(5): 1-7.

- Kurimori S, Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Watanabe M, Takano T (2007) Calculation of prefectural disability-adjusted life expectancy (DALE) using long-term care prevalence and its significance as a health indicator. Health Policy 76(3): 346-358.

- Kondo K (2002) Why does the elderly requiring nursing care belong to the low-income group? Shakai Hoken Junp, pp. 6-11.

- Hideaki S, Taro DV, Yoko S, Ishikawa L, Yangming Z (2002) Factors of under-utilization of home care services under long-term care insurance system. Japanese public health magazine 49(5): 425-436.