Caesarian Births-Necessity or Luxury? Evidence from Namibia 2013 DHS

Pazvakawambwa L*

Department of Statistics and Population Studies, University of Namibia, Namibia

Submission: March 06, 2017; Published: April 06, 2017

*Corresponding author: Pazvakawambwa L, Department of Statistics and Population Studies, University of Namibia, Namibia, Email: lpazvakawambwa@unam.na

How to cite this article: Pazvakawambwa L. Caesarian Births-Necessity or Luxury? Evidence from Namibia 2013 DHS. JOJ Nurse Health Care. 2017; 1(2): 555556. DOI: 10.19080/JOJNHC.2017.01.555556

Abstract

Caesarian sections are on the rise worldwide. These operations are usually performed in the interest of mother and child health. However, despite the tried and tested safety of the procedure WHO advises that caesarian births of all geographical locations should not exceed 15%. This papers establishes the prevalence and non-medical determinants of caesarian births in Namibia based on cross-sectional data from the 2013 Namibia DHS multivariate logistic regression. Prevalence of caesarian births was 13.8 %. Caesarian births were influenced by maternal age, region, religion, wealth index, parity and place of delivery. Efforts should be made to maintain low levels of caesarian births and introduce awareness programs on the negative effects of caesarian section.

Keywords: Caesarian births; Determinants; Namibia; DHS

Introduction

Caesarian section rates continue to rise in many countries with good access to medical services but this increase is not associated with improvement in perinatal mortality or morbidity. Gibbons et al. [1] estimated that in 2008, across the world, 3.18 million additional caesarian sections were needed and 6.2 million unnecessary caesarian sections were performed. The cost of the global "excess" was estimated to amount to approximately USD2.32 billion, while the cost of the global "needed" caesarian section was only approximately USD432 million. "Excess" caesarian section can therefore have important negative implications for health equity both within and across countries. Druzin & El Sayed [2] argued that an increasing caesarian section rate adds an economic burden on already stressed medical systems because of the incremental cost of caesarian section compared to vaginal delivery. Rising caesarian section rates are associated with a longer length of stay and higher hospital occupancy rate. They further highlighted that the incidence of placenta accrete is increasing in conjunction with the rising caesarian rate. The added costs associated with this complication (MRI, interventional radiology, transfusion, hysterectomy, and intensive care admission) could be prohibitive. It has also been demonstrated that infants born by scheduled caesarian delivery are more likely to require advanced nursery support than those born to mothers attempting vaginal delivery. An increase in in caesarian births in Free Delivery and Caesarian Policy (FDCP) was observed in Senegal but these trends were not found in non-FDCP regions. The cost per additional caesarian under the policy was USD467 while the cost per additional supervised normal delivery was only USD21.

In developing countries, Stanton & Holtz [3] showed that caesarian births were extremely low among the very poor. Only in 5 countries did the very poor have caesarian sections rates exceeding 5%. They attributed this to the fact that especially in sub-Saharan Africa, large segments of the population have little access to potentially life-saving caesarian section, whereas in some middle-income countries, more than half the population have rates in excess of medical need. These results deserve immediate attention of policy makers at national and international level. Namibia is classified as an upper-middle income country but still has high maternal mortality, maybe due to limited access to potentially life-saving caesarian section especially in remote areas.

A qualitative analysis of the attitudes of obstetricians to perform a caesarian section on maternal request in the absence of a medical indication was conducted in Europe. Compliance with a hypothetical woman's request for elective caesarian simply because it was "her choice" was lowest in Spain (15%), France (19%), Netherlands (22%); highest in Germany (75%) and UK (79%); and intermediate in the remaining countries. Multivariate logistic regression results indicated that country of practice, litigation, and working in a university affiliated hospital was associated with a physician's likelihood to agree to the patient’s request. Cultural factors, legal liability, and variables linked to the specific perinatal care organization the various countries played a role. The authors expressed the need for understanding the motivation, value and fears underlying a woman's request for caesarian delivery [4]. Common reasons reported for maternal demand for caesarian section in Nigeria were fear of labour pains, fear of poor labor outcome, fear of fecal, and urinary incontinence. More than 50% of those wishing to request caesarian section would likely be criticized by their husbands highlighting the role of the male partner in the formulation of sustainable policies or guidelines for maternal demand for caesarian section in developing countries.

Caesarian births in the United States had a steady decrease from 1991 to 1996 and then they increased from 1996 to 2006 for women of all ages, race ethnic groups, and gestational ages in all states [5,6]. The practice of maternal request caesarian section is increasing in the US because patient autonomy and a woman’s right to choose her mode of delivery should be respected. Zhang et al. [7] proposed that to decrease caesarian delivery rate in the United States, reducing primary caesarian delivery is the key. They felt that increasing vaginal birth after previous caesarian birth is urgently needed and that caesarian section for dystocia should be avoided before the active phase is established particularly in nulliparous women and induced labour. The practice of caesarian delivery on maternal request as a standard of care or as a mandated part of patient counseling for delivery may result in a highly questionable use of finite resources [6]. The rise in caesarian section rates also raised a range of concerns in Latin America and South Asia especially for non-emergency purposes, not least the progressive shift of resources to non-essential medical interventions in resource poor settings and additional health risks to mothers and new-borns following caesarian sections. The study investigated whether high elective caesarian section rates were driven by medical, institutional individual and family decisions. Their results showed that women of higher socioeconomic backgrounds, who had better access to antenatal services, were most likely to undergo a caesarian section. Women who exchanged reproductive information with family and friends were less likely to experience a caesarian section than their counterparts. The authors highlighted the need to pursue community based approaches for curbing rising caesarian section rates in resource poor settings [8].

A variety of factors influencing caesarian section have been suggested. In Australia, O'Leary et al. [9] using logistic regression, established that between 1984-88 and 1999 to 2003, the likelihood of women having caesarian section increased by a factor of 2.35 times and the likelihood of an emergency increased by 1.89 times. These caesarian section increases remained even after adjusting for their strong associations with socio-demographic factors, obstetric risk factors and obstetric complications. Caesarian sections were higher in older mothers Bayrampour & Heaman [10], especially those older than 4o years of age and in nulliparous women. In Norway, Tollanes et al. [11] found that the relative risk of caesarian section for both planned and emergency caesarian section was highest among the least educated, followed by those with medium education and the differences gradually increased during 1967 to 2004. The rate of primary elective caesarian deliveries continues to rise, owing in part to the widespread perception that the procedure is of little or no risk to healthy women. In Canada, healthy women who underwent a primary caesarian delivery for breech presentation constituted a surrogate "planned caesarian group", for comparison with an otherwise similar group of women who had planned to deliver vaginally. The planned caesarian group had increased postpartum risks of cardiac arrest, wound hematoma, hysterectomy, major puerperal infection, anesthetic complications, venous thromboembolism, hemorrhage requiring hysterectomy, and stayed in hospital longer compared to those in the planned vaginal group. The study concluded that the risks of severe maternal morbidity associated with planned caesarian delivery are higher than those associated with planned vaginal delivery; and that these risks should be considered by women contemplating an elective caesarian delivery and by their physicians [12]. In Italy, age and the place of residence were the sole social predictors of caesarian births [13]. A significant statistical relationship was found between age of the mother, level of education, occupational status, type of previous delivery, person supervising the pregnancy, and dissatisfaction about delivery were more frequent in women in women who underwent caesarian section than those who gave birth by natural vaginal delivery [14]. Singleton caesarian rates for non-hispanic black women increased at a faster pace among all pre-term gestational age-groups compared with non-hispanic white and Hispanic women [15].

In a semi-rural hospital in Northern Namibia, Dillan et al. [16] established that most caesarian sections were done for dystocia (34%) followed by repeat caesarian section (31%). The true conjugate (distance between the promontorium to mid pubic bone) was significantly smaller in these recurrent groups when compared to non-recurrent indications. The authors proposed the introduction of Delee Pelvimetry and a caesarian record keeping system to analyze indications for caesarian sections to reduce unnecessary caesarian sections. The increase in the rate of unnecessary caesarian section throughout the world, and its adverse effect on maternal and child health, financial burden imposed on families and health systems, highlighted the importance of studies to identify non-medical factors that affect decision making concerning the type of delivery as well as indications of caesarian section [17].

Methods

The study was based on the 2013 Namibia DHS. The objective of the study was to establish the prevalence and determinants of caesarian births (CB). The response variable was whether a caesarian birth had occurred or not occurred.Potential predictors of caesarian births as guided by literature and availability of data included region, rural/urban place of residence, maternal age, educational level, religion, socioeconomic status, employment status, pre-natal doctor, total children born, timing of first antenatal checkup, place of delivery and birth weight. Descriptive summary statistics were in form of frequency tables, charts and graphs. Multivariate logistic regression was used to establish the factors influencing the occurrence of a caesarian birth.

Results

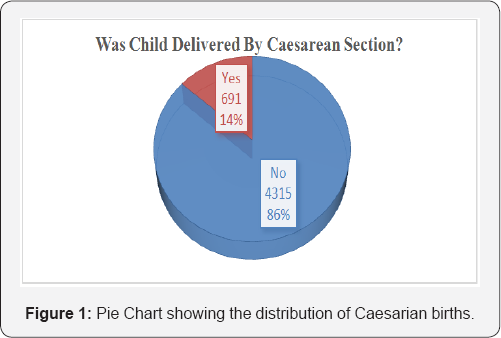

The pie chart in Figure 1 shows the distribution of births by mode of delivery (by caesarean section or not). 13.8% of the babies were delivered through caesarean section.

The prevalence of caesarian births was 13.8%. The prevalence of caesarian birth has been increasing since 1992. Figure 2 shows the trend in percentage of caesarian births from 1992 to 2013. Data was not available on the DHS 2000 variable.

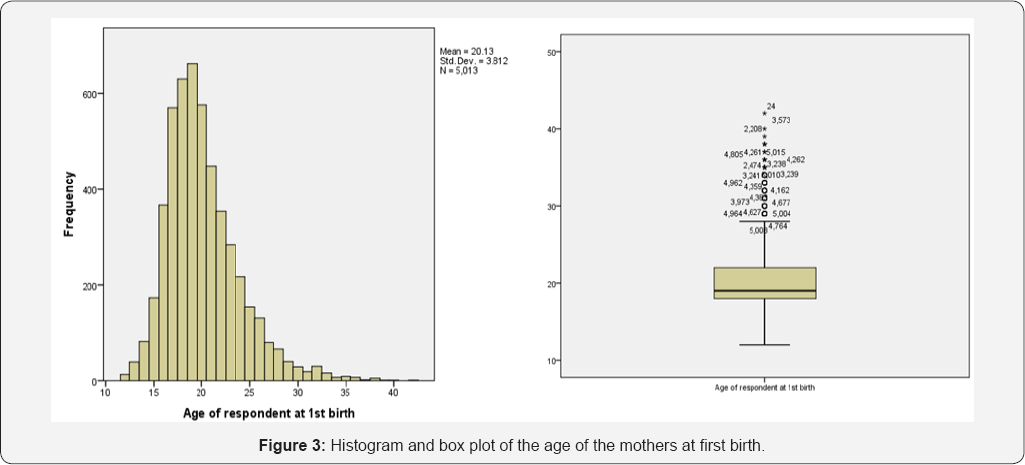

The ages of the mothers at their first birth ranged from 12 to 42 years with a mean of 20.13 years and a standard deviation of 3.812. The distribution of the ages at first birth is presented in the histogram and box plot in Figure 3. The ages skewed towards younger ages.

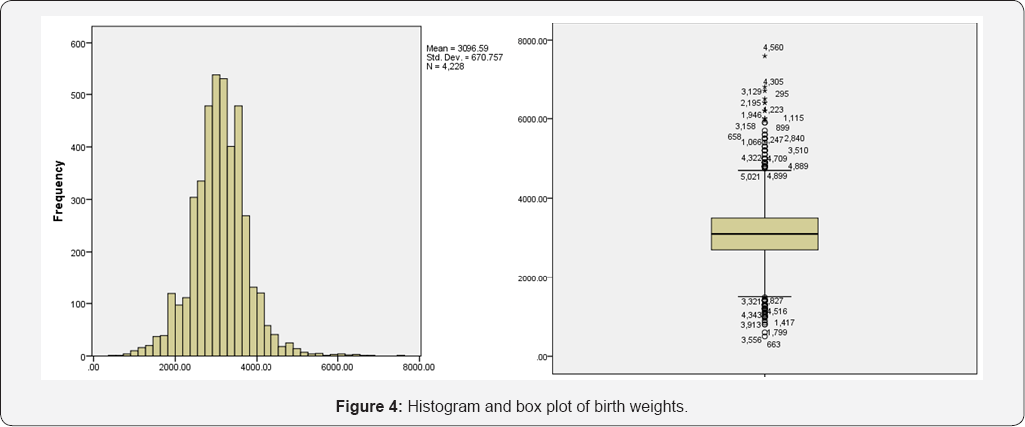

The weights of the babies at birth ranged from 500 to 4560 grams with a mean of 3097 grams and a standard deviation of 670 grams. The distribution of the birth weights are illustrated in histogram and boxplot in Figure 4. The birth histogram and box plot are fairly symmetrical suggesting no gross violation of the normality assumption.

The background characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The distribution of the mothers by age-group was 15-19 (6.3%); 20-24 (24.2%); 25-29 (24.6%); 30-39 (19.5%); 35-39 (14.5%); 40-44(7.1%) and 45-49 (2.0%). Their regional distribution was as follows: Zambezi (8.2%), Erongo (7.2%), Hardap (6.7%), Karas (7.4%), Kavango (10.2%), Khomas (7.9%), Kunene (8.5%), Ohangwena (9.3%), Omaheke (6.9%), Omusati (7.4%), Oshana (5.5%), Oshikoto (6.9%) and Otjozonjupa (8.0%). Most of the mothers resided in rural areas (54.6%). The highest education level of the mothers ranged from no education (8.4%), primary (23.7%) and secondary (63.1%) to higher education (4.8%).

The religions of the mothers were Roman Catholic (21.7%), Protestant/ Anglican (23.3%), ELCIN (38.6%), Seventh day Adventist (6.0%), no religion (2.3%) and others (7.9%). Most of the mothers were not working (59.2%) and only 14.7% had been attended by a doctor for their pre-natal care. The socioeconomic status of the mothers, measured by the wealth index, showed that 43.6% of the mothers were poor, 22.2% were in the middle, and 34.1% were rich. It was also interesting to note that only 25.5% of their husbands attended ANC visits for the current pregnancy.

The timing of the first antenatal checkup was mostly between 0 and 5 months (82.6%) with the remaining 17.4% mothers only going for their first antenatal checkup after 6 months of pregnancy with regard to fertility, the total children born to each mother were 1 (24.9%), 2 (26.2%), 3 (18.0%), 4(12.2) and 5 or more (18.7%). It was worrying to note that 50.7% of the mothers had had their first birth during their teenage years. The majority of the babies born were female (50.5%). The birth weight of the babies was mostly between 2501 and 3500 grams (51.8%) with a sizeable percentage of the babies having low birth weight (500-2500) (14.8%) and high birth weight (above 4500 grams) (18.0%). Most of the mothers had been informed about pregnancy complications (74.0%) yet only 33.1% of them had only 10 or more antenatal visits during pregnancy.

The distribution of the mothers by age-group was 15-19 (6.3%); 20-24 (24.2%); 25-29 (24.6%); 30-39 (19.5%); 3539 (14.5%); 40-44(7.1%) and 45-49 (2.0%). Their regional distribution was as follows: Zambezi (8.2%), Erongo (7.2%), Hardap (6.7%), Karas (7.4%), Kavango (10.2%), Khomas (7.9%), Kunene (8.5%), Ohangwena (9.3%), Omaheke (6.9%), Omusati (7.4%), Oshana(5.5%), Oshikoto (6.9%) and Otjozonjupa (8.0%). Most of the mothers resided in rural areas (54.6%). The highest education level of the mothers ranged from no education (8.4%), primary (23.7%), secondary (63.1%) to higher education (4.8%).

The religions of the mothers were Roman Catholic (21.7%), Protestant/ Anglican (23.3%), ELCIN (38.6%), Seventh day Adventist (6.0%), no religion (2.3%) and others (7.9%). Most of the mothers were not working (59.2%) and only 14.7% had been attended by a doctor for their pre-natal care. The socioeconomic status of the mothers, measured by the wealth index, showed that 43.6% of the mothers were poor, 22.2% were in the middle, and 34.1% were rich. It was also interesting to note that only 25.5% of their husbands attended ANC visits for the current pregnancy.

The timing of the first antenatal checkup was mostly between o and 5 months (82.6%) with the remaining 17.4% mothers only going for their first antenatal checkup after 6 months of pregnancy With regard to fertility, the total children born to each mother were 1(24.9%), 2(26.2%), 3(18.0%), 4(12.2) and 5 or more (18.7%). It was worrying to note that 50.7% of the mothers had had their first birth during their teenage years. The majority of the babies born were female (50.5%). The birth weight of the babies was mostly between 2501 and 3500 grams (51.8%) with a sizeable percentage of the babies having low birth weight (500-2500) (14.8%) and high birth weight (above 4500 grams) (18.0%). Most of the mothers had been informed about pregnancy complications (74.0%) yet only 33.1% of them had had only 10 or more antenatal visits during pregnancy.

Bivariate Analysis Results

Bivariate analysis revealed that the possibility a caesarean birth was significantly associated with the mother's age (Chi-square=14.160, p=0.028); region (Chi-square=177.536, p>0.001); place of residence (Chi-square=137.599, p>0.001); highest educational level (Chi-square=242.122, p>0.001); religion (Chi-square=39.093, p>0.001); employment status (Chi-square= 58.921, p>0.001); attendance by pre-natal doctor (Chi-square=226.798, p>0.001); whether husband attended ANC visits for the pregnancy (Chi-square=48.189, p>0.001); socio-economic status (Chi-square=226.593, p>0.001); total children ever born (Chi-square=89.777, p>0.001); the timing of the first antenatal checkup (Chi-square=12.029, p=0.001); birth weight of the child (Chi-square=68.197, p>0.001); place of delivery (Chi-square=372.18, p>0.001); number of antenatal visits during pregnancy (Chi-square=9.210, p>0.001);and age at first birth (Chi-square=104.387, p>0.001). However, the possibility of caesarean birth was significantly influenced by the sex of the child or whether the mother had been informed about pregnancy complications.

Logistic Regression Results

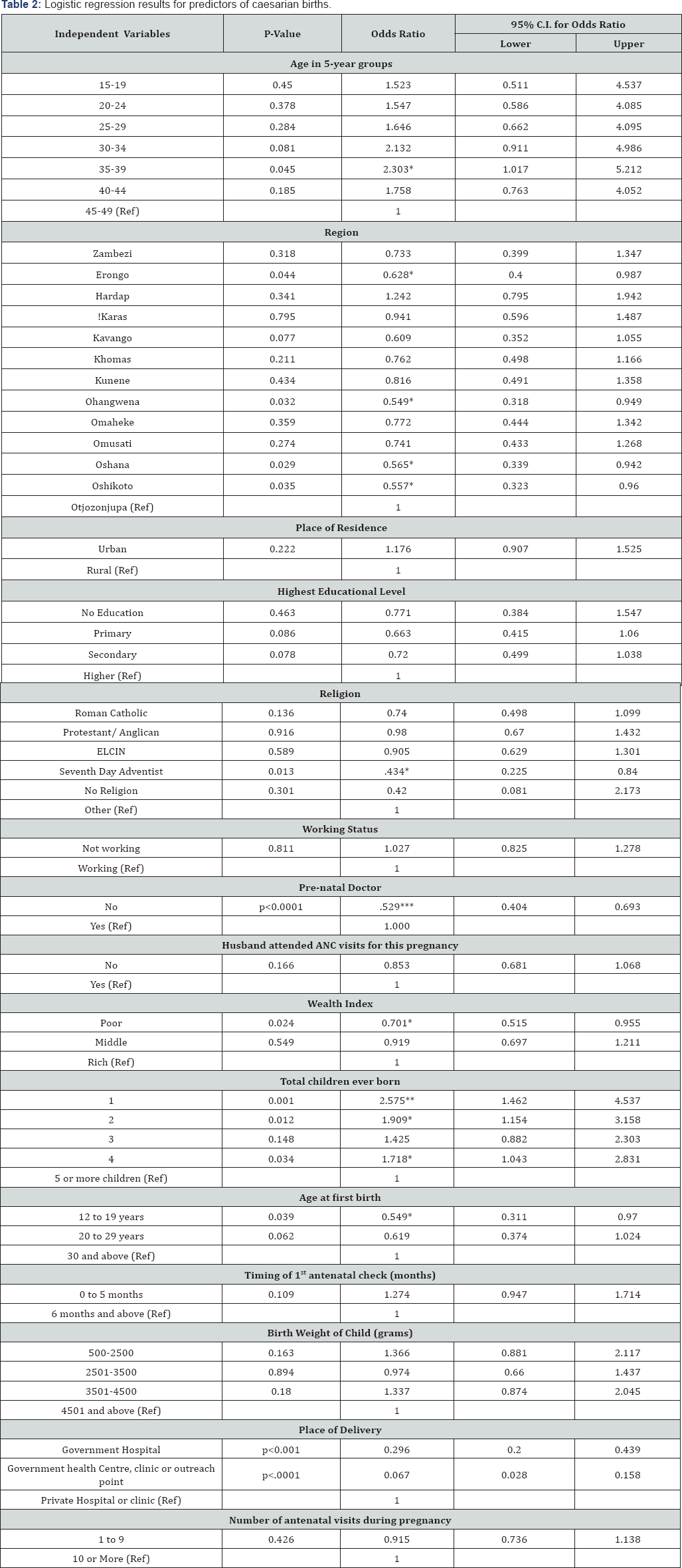

The variables with significant bivariate relationship with the occurrence of a caesarian birth were input into the logistic regression model. Results of logistic regression are presented in Table 2.

Regression results indicated that only women aged 35-39 (0R=2.303, p=0.045) were more likely to undergo caesarian section compared to those in the 45-49 age-group. Women form Erongo (0R=0.628, p=0.044); Ohangwena (0R=0.549, p=0.032); Oshana (OR=0.565, p=0.029) and those from Oshikoto region (OR=0.557, p=0.035) were less likely to undergo caesarian section compared to their counterparts from the Otjozonjupa region. With regard to religion, women from the Seventh Day Adventist Church (OR=0.434, p=0.013) were less likely to undergo caesarian section compared to those from other religions. Women who were aged 15-19 years at the birth of their first baby, were less likely to undergo a caesarian section (OR=0.549, p=0.039) compared to those aged 30 and above. Those whose place of delivery was either a government hospital (OR=0.296, p>0.001), or government health centre, clinic, or outreach point (OR=0.067, p>0.001) were less likely to undergo caesarian section compared to those who delivered at a private hospital or clinic.

Results also indicated that women with no pre-natal doctor (OR=0.529, p>0.001) were less likely to undergo a caesarian section compared to those who had one. Poor women were also less likely to have a caesarian section compared to their rich counterparts (OR=0.701, p=0.024). The likelihood of a caesarian section was higher among women with a total number of children ever born to them of one child (OR=2.575, p=0.001); two children (OR=1.909, p=0.012); and four children (OR=1.718, p=0.034) compared to those with a total five or more children. The woman's place of residence, educational level, working status, the timing of the first antenatal checkup, number of antenatal visits during pregnancy, whether the husband attended ANC visits for that pregnancy, and the birth weight of the baby did not significantly influence the likelihood of a caesarian section.

Discussion

Only women aged 35-39 were more likely to undergo a caesarian section compared to the women in the oldest reproductive category. In contrast, Bayrampour & Heaman [10] found caesarian sections to be higher among older women. There were significant regional differentials in the likelihood of caesarian sections in Namibia. This could be due to the fact that access to maternal health services may not be uniform across all regions [18]. There were significant differentials in the likelihood of a caesarian section due to the woman's region. Religion, which is often associated with cultural factors may play a role in a woman's reproductive health decisions [19]. Women with no prenatal doctor were less likely to undergo a caesarian section compared to those who had one. The place of delivery also influenced the likelihood of a caesarian section with women delivering at public facilities being less likely to undergo a caesarian section compared to those delivering at private facilities. Most private facilities are expensive and as such they divide patients along socio-economic lines. The socio-economic status of the woman (measured by the wealth index) was also a significant predictor of the likelihood of a caesarian section with the poor being less likely to have a caesarian birth compared to their rich counterparts. This could also be linked to the fact that the rich women can afford private medical attention e.g. a private doctor and can even opt for the more expensive elective caesarian section rather than the normal vaginal delivery unlike the poor. In addition, the rich women tend to have more autonomy on their reproductive health decisions [20-23].

Conclusion

Caesarian sections rates are increasing in Namibia even though they are still within the WHO threshold. Caesarian births were influenced by maternal age, region, religion, presence of a prenatal doctor, socio-economic status, total children ever born, timing of first birth and place of delivery. Efforts should be made to maintain low levels of caesarian birth increasing access of maternal health services in all regions and awareness programs on the negative effects of caesarian section.

References

- Gibbons L, Belizan JM, Lauer JA, Betran AP, Merialdi M, et al. (2010) The global numbers and costs of additionally needed and unnecessary caesarean sections performed per year: overuse as a barrier to universal coverage. World health report 30: 1-31.

- Druzin ML, El-Sayed YY (2006) Cesarean delivery on maternal request: wise use of finite resources? A view from the trenches. Semin Perinatol 30(5): 305-308.

- Stanton CK, Holtz SA (2006) Levels and trends in cesarean birth in the developing world. Stud Fam Plann 37(1): 41-48.

- Habiba M, Kaminski M, Da Fre M, Marsal K, Bleker O, et al. (2006) Caesarean section on request: a comparison of obstetricians attitudes in eight European countries. BJOG 113(6): 647-656.

- MacDorman MF, Menacker F, Declercq E (2008) Cesarean birth in the United States: epidemiology, trends, and outcomes. Clinics in perinatology 35(2): 293-307.

- Menacker F, Hamilton BE (2010) Recent trends in cesarean delivery in the United States. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

- Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy UM, Laughon SK, Branch DW, et.al (2010) Contemporary cesarean delivery practice in the United States. Am J obstetrics and gynecology 203(4): 326.e1-326.e2.

- Leone T, Padmadas SS, Matthews Z (2008) Community factors affecting rising caesarean section rates in developing countries: an analysis of six countries. Soc sci med 67(8): 1236-1246.

- O Leary CM, De Klerk N, Keogh J, Pennell C, De Groot J, et al. (2007) Trends in mode of delivery during 1984-2003: can they be explained by pregnancy and delivery complications? BJOG 114(7): 855-864.

- Bayrampour H, Heaman M (2010) Advanced maternal age and the risk of cesarean birth: a systematic review. Birth 37(3): 219-226.

- Tollanes MC, Thompson JM, Daltveit AK, Irgens LM (2007) Cesarean section and maternal education; secular trends in Norway, 19672004. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scand 6(7): 840-848.

- Liu S, Liston RM, Joseph KS, Heaman M, Sauve R, et al. (2007) Maternal mortality and severe morbidity associated with low-risk planned cesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery at term. CMAJ 176(4): 455-460.

- Kambale MJ (2011) Social predictors of caesarean section births in Italy. Afr health sci 11(4): 560-565.

- Ostovar R, Rashidi BH, Haghallahi F, Fararoei M, Rasouli M, et al. (2013) Non-medical factors on choice of delivery (CS/NVD) in hospitals of Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

- Bettegowda VR, Dias T, Davidoff MJ, Damus K, Callaghan WM, et al.(2008) The relationship between cesarean delivery and gestational age among US singleton births. Clin perinatol 35(2): 309-323.

- van Dillen J, Meguid T, Petrova V, Van Roosmalen J (2007) Caesarean section in a semi-rural hospital in Northern Namibia. BMC pregnancy childbirth 7(1): 1.

- Baru R, Acharya A, Acharya S, Kumar AS, Nagaraj K (2010) Inequities in access to health services in India: caste, class and region. Economic and Political Weekly 45(38): 49-58.

- Bryant AS, Washington S, Kuppermann M, Cheng YW, Caughey AB(2009) Quality and equality in obstetric care: racial and ethnic differences in caesarean section delivery rates. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology 23(5): 454-462.

- Declercq E, Menacker F, MacDorman M (2006) Maternal risk profiles and the primary cesarean rate in the United States, 19912002. American journal of public health 96(5): 867-872.

- Getahun D, Strickland D, Lawrence JM, Fassett MJ, Koebnick C, et al.(2009) Racial and ethnic disparities in the trends in primary cesarean delivery based on indications. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 201(4): 422-e1-7.

- Mumtaz Z, Salway S, Bhatti A, Shanner L, Zaman S, et.al (2014) Improving maternal health in Pakistan: toward a deeper understanding of the social determinants of poor Women's access to maternal health services. Am J Public Health 104(1): S17-S24.

- Ronsmans C, Holtz S, Stanton C (2006) Socioeconomic differentials in caesarean rates in developing countries: a retrospective analysis. The Lancet 368(9546): 1516-1523.

- Witter S, Dieng T, Mbengue D, Moreira I, De Brouwere V (2010) The national free delivery and caesarean policy in Senegal: evaluating process and outcomes. Health Policy Plan 25(5): 384-392.