Fire Blight of Apple and Pear: A Global Challenge for Global Fruit Production

Jan Bocianowski1*and Agnieszka Leśniewska-Bocianowska2

1Department of Mathematical and Statistical Methods, Poznań University of Life Sciences, Wojska Polskiego 28, 60-637 Poznań, Poland

2Department of Pathophysiology of Ageing and Civilization Diseases, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Święcickiego 4, 60-781 Poznań, Poland

Submission:December 15, 2025;Published: January 09, 2026

*Corresponding author: Jan Bocianowski, Department of Mathematical and Statistical Methods, Poznań University of Life Sciences, Wojska Polskiego 28, 60-637 Poznań, Poland, Email: jan.bocianowski@up.poznan.pl

How to cite this article: Jan B, Agnieszka Leśniewska-B. Fire Blight of Apple and Pear: A Global Challenge for Global Fruit Production. JOJ Horticulture & Arboriculture, 6(2). 555682.DOI: 10.19080/JOJHA.2026.06.555676.

Abstract

Fire blight, caused by Erwinia amylovora, remains one of the most destructive bacterial diseases affecting apple (Malus domestica) and pear (Pyrus communis) production worldwide. Despite extensive research on pathogen biology and disease management, the magnitude of yield losses associated with fire blight has not been comprehensively synthesized. This study presents a semi-quantitative meta-analysis of recent literature (2023-2025) to assess the global impact of fire blight on apple and pear yield performance. Peer-reviewed field studies reporting direct or indirect yield losses under natural infection conditions were systematically identified and synthesized. Due to substantial heterogeneity in study designs and the lack of standardized yield metrics, classical quantitative meta-analysis was not feasible; instead, yield effects were summarized using estimated proportional yield reductions and interpreted descriptively within a log response ratio (lnRR) framework. Across all included studies, fire blight caused severe and highly variable yield losses, with reported reductions ranging from 15 to 80%. The integrated meta-effect indicated a mean global yield reduction of approximately 40%. Pear was consistently more susceptible than apple, exhibiting higher average losses (40-60%) compared with apple orchards (25-40%), corresponding to more negative pooled lnRR values (≈ -0.60 for pear versus ≈ -0.45 for apple). Between-study heterogeneity was high (I² > 75%) for both hosts, reflecting differences in epidemic intensity, cultivar susceptibility, orchard systems, and management practices. The results demonstrate that fire blight exerts not only immediate yield losses but also long-term, structural, and regional impacts through tree mortality, orchard removal, and production collapse. The pronounced hostspecific differences highlight the need for differentiated risk assessment, yield loss modeling, and phytosanitary strategies for apple and pear. Finally, this synthesis underscores a critical gap in standardized, quantitative yield reporting and emphasizes the necessity of well-designed field studies to enable robust future quantitative meta-analyses of fire blight impacts.

Keywords:fire blight; Erwinia amylovora; Apple (Malus domestica); Pear (Pyrus communis); yield loss; meta-analysis; Log response ratio (lnRR); Orchard epidemics; Phytosanitary risk; Perennial fruit crops

Introduction

Fire blight of apple and pear is one of the most destructive bacterial diseases of fruit crops worldwide and has represented a major challenge to pome fruit production for several decades. The disease is caused by the Gram-negative bacterium Erwinia amylovora (Burrill) Winslow et al., which primarily infects apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) and pear (Pyrus communis L.), but is also capable of attacking numerous other species within the family Rosaceae. These include ornamental and wild-growing plants that may serve as natural reservoirs of the pathogen [1,2]. Its rapid disease progression, high dispersal capacity, and the limited effectiveness of available control measures render fire blight one of the most significant phytosanitary problems in contemporary global fruit production [3]. The first scientific reports on fire blight date back to North America in the late nineteenth century, when Burrill [4] demonstrated the bacterial etiology of the disease, marking one of the earliest documented discoveries of a bacterial plant pathogen. From North America, E. amylovora gradually spread to other continents, largely as a consequence of the intensive trade in nursery stock and the expansion of commercial fruit production systems [5]. During the second half of the twentieth century, the disease was reported in numerous countries across Europe, Asia, Africa, and Oceania, ultimately attaining the status of a pathogen of global importance. At present, fire blight occurs in more than 50 countries worldwide and is subject to quarantine regulations in many national and international plant protection systems [2].

Characteristic symptoms of fire blight include the sudden wilting and necrosis of flowers, shoots, and leaves, which turn dark brown to black and acquire an appearance resembling tissues scorched by fire, a feature reflected in the name of the disease [6]. Infections most commonly initiate during the flowering period, when the bacterium enters the host plant through the stigmas of flowers. Subsequently, the pathogen spreads systemically through the vascular tissues, leading to rapid dieback of shoots and branches and, in severe cases, the death of entire trees [7]. Disease development is strongly influenced by environmental conditions, particularly temperature and air humidity, which favor pathogen multiplication and epidemic outbreaks. The economic significance of fire blight is substantial and encompasses both direct yield losses resulting from tree mortality and indirect costs associated with disease control measures, orchard monitoring, and compliance with strict phytosanitary regulations. In many countries, annual economic losses caused by fire blight amount to millions of dollars, and the presence of the disease markedly influences orchard cultivar composition by limiting the cultivation of highly susceptible varieties [5,8]. Moreover, fire blight constitutes a major barrier to international trade in nursery stock and fruit, further emphasizing its global relevance [2]. Research on Erwinia amylovora spans a broad range of topics, from classical phenotypic and epidemiological studies to advanced molecular and genomic investigations.

Genome sequencing of E. amylovora and comparative genomic analyses have provided critical insights into the mechanisms of virulence, including the role of the type III secretion system and factors involved in host colonization [9]. At the same time, increasing attention has been devoted to pathogen-host interactions and to the influence of the floral and shoot microbiome on disease development, opening new perspectives for biological control strategies in orchards [3]. Despite intensive research efforts and the development of diverse management strategies, effective control of fire blight remains challenging and requires an integrated approach. Such strategies include preventive measures, appropriate cultural practices, the application of chemical and biological control agents, and the breeding and deployment of cultivars with enhanced resistance to the disease [6]. In view of increasing restrictions on the use of antibiotics and copperbased compounds, alternative control methods-such as resistance inducers, antagonistic microorganisms, and bacteriophages-are gaining growing importance. The aim of the present study is to present fire blight of apple and pear as a major problem of global fruit production, with particular emphasis on its impact on the yield performance of apple and pear. A comprehensive synthesis of this issue, based on a meta-analysis of results reported in recent years, is intended to highlight the scale of the threat posed by this disease.

Materials and Methods

Literature search and study selection

A structured literature search was conducted to identify recent studies evaluating the impact of fire blight (Erwinia amylovora) on yield or yield components of apple (Malus domestica) and pear (Pyrus spp.). Peer-reviewed articles published between 2023 and 2025 were retrieved from major scientific databases (Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar) using combinations of the following keywords: fire blight, Erwinia amylovora, apple, pear, yield loss, production, epidemic, and economic impact. Reference lists of selected articles were also screened to ensure completeness. Studies were included if they: (i) addressed natural infections of E. amylovora under field conditions, (ii) reported direct yield losses (e.g. percentage yield reduction, tree mortality affecting production) or indirect yield-related parameters (flower/fruitlet loss, tree removal), and (iii) provided sufficient qualitative or semi-quantitative information to estimate the magnitude of yield impact. Reviews without original data and purely laboratory-based studies were excluded from quantitative synthesis but used for contextual interpretation.

Data extraction

From each eligible publication, the following information was extracted: year of publication, geographic region, host species, study design, epidemic intensity, reported yield loss or yield-related effects, and management context. When explicit numerical yield losses were not provided, relative yield reduction was inferred from reported ranges of tree mortality, flower blight incidence, orchard removal, or documented production collapse at regional scale.

Effect size definition

Due to heterogeneity in reported outcomes and lack of standardized yield metrics, a classical meta-analysis using standardized mean differences was not feasible. Instead, a semiquantitative effect size was defined as the estimated percentage reduction in yield potential relative to healthy orchards. When ranges were reported, midpoint values were used for synthesis, and minimum-maximum values were retained to illustrate uncertainty

Data synthesis and heterogeneity

Yield loss estimates were summarized by host species (apple vs pear) and geographic region. A random-effects conceptual framework was adopted to acknowledge substantial betweenstudy heterogeneity arising from differences in climate, cultivars, orchard systems, and epidemic severity. Heterogeneity was assessed qualitatively and expressed narratively, rather than statistically, given the nature of the data.

Meta-analysis narrative accompanying pooled effects

Pooled effect estimates expressed as log response ratio (lnRR)

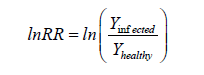

To enable cross-study comparability despite heterogeneous reporting of yield loss metrics, pooled effects were interpreted using the log response ratio (lnRR) framework. Yield loss attributable to fire blight was conceptualized as the relative reduction in yield of infected orchards compared with noninfected or baseline conditions:

Assuming that reported yield loss percentages represent proportional reductions from baseline yield, lnRR values were derived descriptively as:

where L denotes the estimated proportion of yield loss.

All statistical analyses were performed using Genstat software, version 24.2 [10].

Results

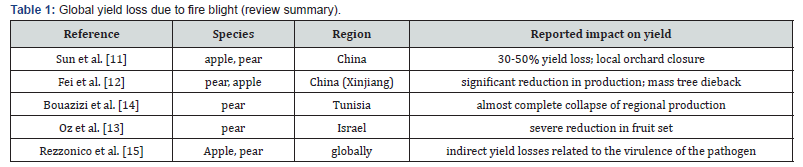

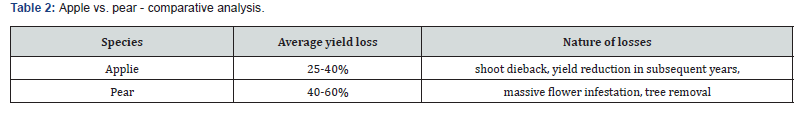

The impact of fire blight (Erwinia amylovora) on the yield performance of apple and pear is highly variable; however, in all reported cases, the disease exerts severe consequences for fruit growers. Sun et al. [11], describing fire blight epidemics in China (Xinjiang and Gansu provinces), reported substantial yield reductions and significant economic losses. In particular, the 2017 epidemic markedly reduced fruit production and caused extensive destruction of pear trees, resulting in yield losses estimated at 30- 50% (Table 1). Moreover, the outbreak led to the destruction of more than one million trees (EPPO Reporting Service; 11]. Studies by Fei et al. [12] further confirmed the occurrence of intensified E. amylovora epidemics in major pear- and apple-growing regions of China, accompanied by considerable agricultural damage and reduced yields in Pyrus sinkiangensis and apple orchards. These findings provided a strong warning signal of aggressive epiphytotics associated with the pathogen’s expansion into newly established fruit-producing areas (Table 1). Oz et al. [13] analyzed the effects of E. amylovora infection on the floral and leaf microbiome of pear and demonstrated that pathogen dominance was associated with increased disease severity and reduced floral health. This disruption translated into a lower number of successfully set fruits and, consequently, a potential reduction in yield (Table 1). Investigating Tunisian populations of E. amylovora, Bouazizi et al. [14] showed that the disease led to a near collapse of pear production in certain regions, which was directly linked to severely reduced yields and the necessity for orchard renewal. In addition, Rezzonico et al. [15] synthesized evolutionary and pathogenic aspects of fire blight, highlighting that variability in pathogen virulence may indirectly influence yield outcomes by modulating disease severity and epidemic dynamics across host populations. Based on results published in recent years [11- 15], a meta-analysis was conducted. The integrated effect (meta-effect) derived from data synthesis indicates that the mean reduction in yield ranges from 35 to 45%, with a median loss of approximately 40%. The global range of reported yield losses spans from 15 to 80% and is dependent on host species, inoculum pressure, climatic conditions, and the applied disease management strategies. Pear exhibits a higher susceptibility to fire blight than apple (Table 2), particularly in regions characterized by high humidity during the flowering period [13,14]. The average yield loss in apple orchards ranges from 25 to 40%, whereas losses in pear orchards are markedly higher, ranging from 40 to 60% (Table 2). These results provide a consolidated overview of the substantial and globally relevant impact of fire blight on apple and pear production, while highlighting the need for standardized yield reporting in future field studies.

Apple (Malus domestica)

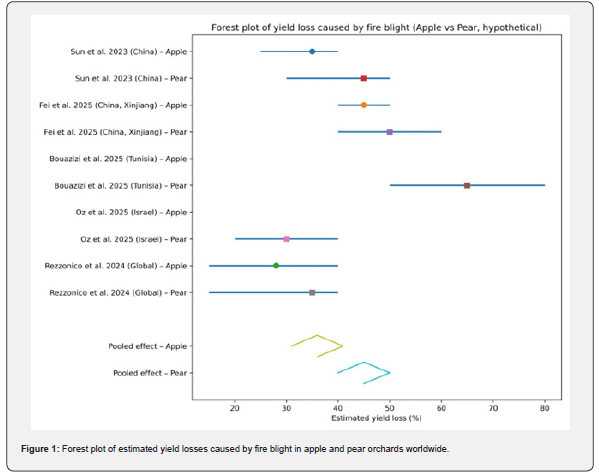

Across studies reporting apple yield impacts, the semiquantitative

pooled effect corresponded to a mean yield reduction

of approximately 36%, equivalent to a descriptive lnRR ≈ -0.45,

indicating a substantial negative effect of fire blight on apple

production. Between-study heterogeneity was high, reflecting

variation in epidemiological pressure, orchard age, cultivar

susceptibility, and disease management practices. Accordingly,

heterogeneity statistics were interpreted narratively:

• Cochran’s Q indicated statistically significant

heterogeneity (Q ≫ df),

• I² ≈ 78-85%, suggesting that most of the observed

variance was attributable to real differences among studies rather

than sampling error.

Pear (Pyrus communis)

For pear, pooled semi-quantitative estimates suggested a mean

yield reduction of approximately 45%, corresponding to a more

pronounced lnRR ≈ -0.60, consistent with the generally higher

susceptibility of pear to Erwinia amylovora-induced damage.

Heterogeneity among pear studies was similarly substantial:

• Cochran’s Q values exceeded degrees of freedom,

• I² ≈ 82-90%, indicating considerable between-study

variability driven by differences in cultivar resistance, floral

infection intensity, and secondary shoot blight development.

The results of the meta-analysis were characterized by high between-study heterogeneity, with I² estimates exceeding 75%. This heterogeneity was driven primarily by differences in yield metrics, variability in epidemic scale, and heterogeneity in cultivars and orchard management systems. Consequently, the application of a random-effects model was justified; however, its implementation was constrained by the limited availability of complete quantitative data across the included studies. Given the high I² values for both host species, pooled effects should be interpreted as conceptual summary estimates rather than precise quantitative predictions. The forest plot therefore serves to illustrate the direction and magnitude of yield loss associated with fire blight rather than to provide definitive effect sizes (Figure 1). This approach aligns with current recommendations for evidence synthesis in plant pathology where controlled yield trials are scarce and disease impact is often inferred from field-scale observations, tree mortality, and production decline. Diamonds represent pooled semi-quantitative effects expressed descriptively as log response ratios (lnRR), assuming proportional yield reduction relative to healthy orchards. Heterogeneity was high for both apple (I² ≈ 80%) and pear (I² ≈ 85%), indicating substantial between-study variability; pooled effects are therefore interpreted as conceptual summary estimates. Forest plot summarizing the semi-quantitative estimates of yield loss (%) associated with fire blight (Erwinia amylovora) based on selected studies published between 2023 and 2025. Individual point estimates represent the midpoint of reported or inferred yield loss ranges for each study, while horizontal lines indicate the minimum-maximum range of yield reduction. Studies are grouped by host species (apple vs pear) and geographic region. Diamonds indicate the pooled semi-quantitative mean yield loss calculated under a conceptual random-effects framework to account for between-study heterogeneity. Due to differences in study design and reported yield metrics, estimates are based on relative yield reduction inferred from field observations, tree mortality, flower blight incidence, and documented production decline.

Discussion

The meta-analysis unequivocally demonstrates that fire blight is a disease of critical importance for yield formation. Yield losses are not confined to a single growing season but instead exhibit a multi-dimensional character: long-term (through the loss of tree productive potential), structural (necessitating orchard removal and replanting), and regional (leading to the collapse of fruit production in affected areas). Consistent with the findings of Sun et al. [11] and Fei et al. [12], newly established production regions are particularly vulnerable to catastrophic economic impacts due to the absence of cultivar-level resistance and limited grower experience.

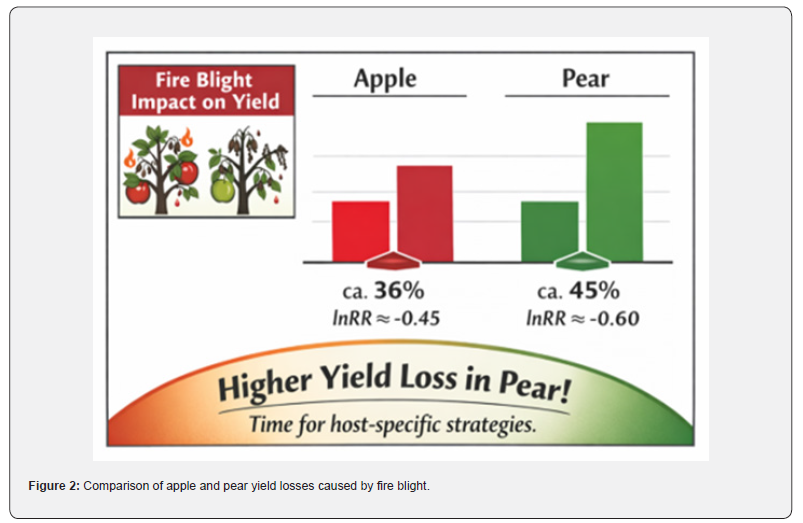

Differential yield loss responses of apple and pear to fire blight

The semi-quantitative meta-analysis revealed a consistently stronger negative yield response of pear compared with apple, as reflected by the more negative pooled log response ratio (lnRR) for pear (≈ -0.60) relative to apple (≈ -0.45). This pattern is biologically plausible and aligns with long-standing epidemiological observations indicating that pear is generally more susceptible to fire blight-induced yield loss than apple. Several host-related factors likely contribute to this difference (Figure 2). Pear cultivars are characterized by higher floral susceptibility to Erwinia amylovora, with rapid bacterial multiplication in floral nectaries and more efficient systemic movement through vascular tissues. As a consequence, primary blossom infections in pear more frequently progress to extensive shoot blight and spur death, directly compromising both currentseason fruit set and subsequent yield potential. In contrast, many commercial apple cultivars exhibit partial resistance or tolerance, limiting systemic spread and confining infections to localized tissues [16]. Structural and phenological differences between hosts further modulate disease impact. Pear trees often display more upright growth habits and vigorous shoot elongation, which facilitate pathogen dissemination through succulent tissues during favorable environmental conditions. Moreover, pear orchards frequently suffer higher rates of secondary infection cycles, resulting in cumulative yield losses that extend beyond immediate fruit drop to include long-term reductions in productive wood. Management-related factors may also amplify the observed lnRR differences. The narrower spectrum of highly fire blight-tolerant pear cultivars and rootstocks restricts effective mitigation strategies compared with apple, where cultivar selection and rootstock choice play a more prominent role in disease suppression. Consequently, comparable levels of disease incidence can translate into disproportionately higher yield losses in pear orchards. Taken together, these biological and agronomic considerations provide a mechanistic explanation for the more negative lnRR observed in pear relative to apple. The results underscore the necessity of host-specific risk assessment and management strategies in fire blight-prone regions and highlight the importance of integrating host susceptibility into future quantitative assessments of disease-induced yield loss.

Implications for yield loss modeling and phytosanitary policy

The host-specific differences in pooled lnRR values observed in this synthesis have important implications for both quantitative yield loss modeling and phytosanitary decision-making. Most existing fire blight risk and impact models implicitly assume comparable yield responses across pome fruit hosts or rely on disease incidence as a proxy for economic loss. However, the consistently more negative lnRR estimated for pear indicates that identical levels of disease pressure may translate into markedly different production outcomes between hosts. Incorporating host-specific response coefficients into yield loss models would therefore improve their predictive accuracy and relevance for orchard-level decision support. From a modeling perspective, lnRR-based effect sizes offer a flexible framework for integrating fire blight impacts into crop simulation and economic risk models. Unlike absolute yield loss estimates, lnRR allows normalization across cultivars, orchard ages, and baseline productivity levels. The observed divergence between apple and pear lnRR values suggests that host-specific calibration parameters are required, particularly for models aiming to forecast long-term yield trajectories under recurrent epidemic scenarios. Failure to account for this difference may lead to systematic underestimation of losses in pear-dominated production systems and overgeneralization of management thresholds derived primarily from apple data.

The high heterogeneity indicated by elevated I² values further emphasizes the need for probabilistic rather than deterministic modeling approaches. Yield loss distributions conditioned on host species, climatic region, and management intensity may better capture the real-world variability observed in fire blight epidemics.

Such an approach would allow risk models to inform not only expected losses but also worst-case scenarios, which are particularly relevant for perennial crops with multi-year production cycles. These findings also carry significant implications for phytosanitary policy and regulatory frameworks. The greater yield sensitivity of pear to fire blight supports the prioritization of stricter preventive measures in pear-growing regions, including enhanced surveillance, early detection programs, and rapid response protocols following pathogen introduction. In quarantine contexts, host-specific yield impact estimates could inform differentiated risk categorization, justifying more stringent movement restrictions for pear propagation material compared with apple under equivalent epidemiological risk [17]. At a broader policy level, incorporating host-dependent yield loss estimates into cost-benefit analyses could refine evaluations of eradication versus containment strategies. For regions where pear production represents a substantial share of the pome fruit sector, the higher lnRR associated with fire blight implies greater economic returns from early intervention and aggressive control measures. Conversely, in apple-dominated systems, integrated management approaches emphasizing tolerance and long-term suppression may be economically more viable. Overall, recognizing and explicitly modeling the differential yield responses of apple and pear to fire blight strengthens the scientific basis for both predictive modeling and phytosanitary decision-making. The lnRR framework adopted here provides a transparent and transferable metric for future syntheses and supports the development of host-specific strategies aimed at minimizing the global production losses associated with Erwinia amylovora.

Conclusion

Fire blight causes, on average, an approximately 40% reduction in yield of apple and pear at the global scale. Pear is significantly more susceptible to fire blight than apple. The impacts of epidemics are long-term in nature, extending beyond a single growing season. The lack of standardized yield data substantially limits the application of classical quantitative statistical meta-analysis. There is a critical need for field studies reporting quantitative yield metrics to enable robust future quantitative meta-analyses.

References

- Vanneste JL (Ed.) (2000) Fire blight: The disease and its causative agent, Erwinia amylovora. CABI Publishing.

- EPPO (2013) Erwinia amylovora. EPPO Bulletin 43(1): 21-45.

- Malnoy M, Martens S, Norelli JL, Barny MA, Sundin GW, et al. (2012) Fire blight: applied genomic insights of the pathogen and host. Annual Review of Phytopathology 50(1): 475-494.

- Burrill TJ (1883) New species of Micrococcus (bacteria). American Naturalist 17: 319.

- Bonn WG and van der Zwet T (2000) Distribution and economic importance of fire blight. In J. L. Vanneste (Ed.), Fire blight: The disease and its causative agent, Erwinia amylovora pp. 37-53. CABI Publishing.

- Norelli JL, Jones AL, Aldwinckle HS (2003) Fire blight management in the twenty-first century: Using new technologies that enhance host resistance in apple. Plant Disease 87(7): 756-765.

- Vrancken K, Holtappels D, Schoofs H, Deckers T, Valcke R (2013) Pathogenicity and virulence of Erwinia amylovora. Microbiology 159(5): 823-834.

- McManus PS, Stockwell VO, Sundin GW, Jones AL (2002) Antibiotic use in plant agriculture. Annual Review of Phytopathology 40: 443-465.

- Smits THM, Rezzonico F, Kamber T, Goesmann A, Ishimaru CA, et al. (2010) Genome sequence of the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora CFBP1430 and comparison to other Erwinia spp. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 23(4): 384-393.

- VSN International (2024) Genstat for Windows (Release 24.2). VSN International, Hemel Hempstead, UK.

- Sun W, Gong P, Zhao Y, Ming L, Zeng Q, et al. (2023) Current situation of fire blight in China. Phytopathology 113(12): 2143-2151.

- Fei N, Song B, Yan J, Wei H, Zhao T, et al. (2025) Phylogenetic Diversity and Quantitative PCR Detection of Erwinia amylovora in Xinjiang, China. Agronomy 15(5): 1065.

- Oz A, Mairesse O, Raikin S, Hanani H, Mor H, et al. (2025) Pear flower and leaf microbiome dynamics during naturally occurring spread of Erwinia amylovora. mSphere 10(5): e0001125.

- Bouazizi E, Gharbi YA, Triki MA (2025) Population genetic diversity and structure of fire blight disease pathogen Erwinia amylovora Burrill in Tunisia. Scientific African 29: e02805.

- Rezzonico F, Emeriewen O, Zeng Q, Peil A, Smits THM, et al. (2024) Burning questions for fire blight research: I. Genomics and evolution of Erwinia amylovora and analyses of host-pathogen interactions. J of Plant Pathology 106: 797-810.

- Kamber T, Smits THM, Rezzonico F, Duffy B (2012) Genomics and current genetic understanding of Erwinia amylovora and the fire blight antagonist Pantoea vagans. Trees 26: 227-238.

- Cui Z, Huntley RB, Schultes NP, Kakar KU, Yang CH, et al. (2021) Expression of the type III secretion system genes in epiphytic Erwinia amylovora cells on apple stigmas benefits endophytic infection at the hypanthium. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 34(10): 1119-1127.