Abstract

Background: An effective patient-centered approach is essential for managing acne vulgaris, a commonly treated skin disease. While commercially available options include oral and/or topical preparations in fixed doses, compounded formulations allow the qualitative and quantitative composition to be personalized to each patient.

Objective: This study aimed to assess the effectiveness (or non-inferiority) and clinical acceptance of CleodermTM, a ready-to-use, semi-solid vehicle for acne treatment.

Methods: We performed an exploratory randomized, split-face, single-blind clinical trial of 10 patients with facial acne. Participants were randomly assigned to receive two treatments for four weeks, and the hemiface of each treatment was randomly specified. All treatments had the same active ingredients but different

Vehicles: a commercial base or CleodermTM, a ready-to-use vehicle for compounding pharmacies. Lesion counts and global acne severity ratings of bilateral patients’ photographs were performed. Sebum production was visually inspected, and patient self-assessment reports were conducted.

Results: The clinical assessment and bilateral facial photographs showed that baseline Leeds scores for all subjects were similar for all treatments. After four weeks, both sides were graded as slightly better. However, 80% of the subjects had better skin outcomes in the hemiface receiving treatment with CleodermTM compared to the hemiface treated with a commercial vehicle base.

Conclusion: Both subgroups treated with standard active pharmaceutical ingredients compounded in CleodermTM presented better treatment efficacy and less discomfort. This suggests that compounded topical formulations might be an excellent alternative to personalize acne treatment.

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis affecting the pilosebaceous follicles of the skin [1]. It is one of the most common skin disorders worldwide, impacting all age groups, independent of sex and ethnic background [2]. Its prevalence is around 85% in adolescents and young adults, and among adult women is around 12% [3,4]. Acne pathogenesis is multifactorial, involving sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, hypercolonization by Cutibacterium acnes, and complex inflammatory mechanisms [5]. Clinically, acne has a variable presentation, including open or closed comedones (blackheads and whiteheads) and inflammatory lesions, such as papules, pustules, nodules, or cysts [6]. In most patients, the face is affected, and the trunk may also be involved in up to 61% of cases [7]. Acne lesions can progress to scars and/or post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation which can have harmful physical and psychological consequences, including poor self-image, depression, and anxiety [8,9]. Given the high prevalence and impact on patients’ health-related quality of life, early treatment is important to optimize acne management [10,11]. Topical, oral, and physical therapies are available and may be influenced by the patient’s age, preferences, site of involvement, and disease severity [12]. Topical therapies may be used as monotherapy with other topical agents with oral agents.[5] Commonly used oral treatments include antibiotics, hormones, and isotretinoin. In contrast, topical ones can involve benzoyl peroxide, salicylic acid, retinoids, azelaic acid, and antibiotics [13-18]. In addition, previous studies showed that physical interventions, such as peeling and laser therapy, have also improved clinical outcomes [19].

Although various conventional therapies are available, the need for additional safe, convenient, and efficacious topical treatment options for acne remains [20,21]. Moreover, patient-centered acne management is crucial due to its varied presentations, chronicity, and impact on an individual’s well-being [12]. While commercial preparations are available in fixed doses, compounded formulations allow the qualitative and quantitative composition to be personalized to each patient [22]. Therefore, this study aimed at investigating the safety profile and clinical acceptance of CleodermTM, a ready-to-use, semi-solid vehicle for acne treatment [23].

Methods

Study Design

Study participants were recruited from a private dermatology clinic in Barcelona (Spain). The recruitment occurred between November and December 2022, and the study was completed in March 2023. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Inclusion criteria were patients 13 years or older, from both sexes, with moderate to severe acne vulgaris based on physician clinical assessment (at least a Leeds acne severity scale rating of 2 on a 12-point ordinal scale), no chronic diseases or comorbidities, and ability to adhere to the study protocol. Exclusion criteria were age younger than 13 years, pregnancy, acne due to secondary causes, the presence of other dermatological diseases of the face, oral retinoid use within one year of study entry, microdermabrasion of the face within three months of study entry, alpha hydroxy acid, or glycolic acid use within one month of study entry, and a history of dermabrasion or laser resurfacing of the facial skin. Before the study entry, all participants were washed-out from systemic antibiotic use or anti-acne topical treatment for one month. The study was a randomized, split-face, single-blind clinical trial comparing four treatments. Participants were randomly assigned to receive two treatments, and the hemiface of each treatment was randomly specified. All treatments had the same concentration of the same active ingredient but different vehicles. Study participants received specific instructions regarding the treatments. In brief, the topical creams should be applied daily at night in a quantity of 1.0 fingertip units (FTU) (or 1.2 grams, to cover the entire hemiface). Treatments were conducted for four weeks by a dermatologist. Participants were clinically assessed at baseline and four weeks later (study endpoint). Evaluations included formal counts of papules, pustules, cysts, comedones, numbers of inflamed, noninflamed, total acne lesions on the face, and Michaelson’s acne severity score. In addition, a visual examination of sebum production levels was performed. Facial photographs were obtained from each participant’s face front and left, and right profile views. Photographs were taken using standardized studio lighting and subject positioning. Images were obtained at baseline and week 4.

These photographs were subsequently viewed by a dermatologist blinded to which side of the face each treatment was applied. The modified Leeds acne severity scale was used to grade the severity of acne demonstrated by each patient on each side of the face. Also, patients’ impressions of the treatment and the associated results regarding their acne severity and the degree of oiliness of their skin were considered at the end of the treatment phase. During the treatment phase of the study, all participants were instructed about diet, physical activity, and hygiene procedures. They were requested to follow a low-glycemic, junk/ processed/spicy food-free diet with skimmed milk. In addition, it was recommended to avoid strenuous activities, sun exposure, and stressful events. The hygiene instruction included washing their faces with regular soap and water only twice daily and after exercise.

Treatment groups

Study participants were randomly divided into two groups. Subjects in group 1 received adapalene 0.1% + benzoyl peroxide 2.5% in commercial vehicle base (treatment A) one-half of the face, with the contralateral face being treated with adapalene 0.1% + benzoyl peroxide 2.5% in Cleoderm TM (treatment B). Subjects in group 2 received erythromycin 0.3% + benzoyl peroxide 5.0% in commercial vehicle base (treatment C) to one-half of the face, with the contralateral face being treated with erythromycin 0.3% + peroxide benzoyl 5.0% in Cleoderm TM (treatment D).

Statistical analysis

For all endpoints, the change from baseline for the side treated with a commercial vehicle base was compared with the change from baseline for the side treated with CleodermTM in all patients. The efficacy data (lesion counts, global acne severity rating, and sebum production) were visually inspected.

Results

Participant Characteristics

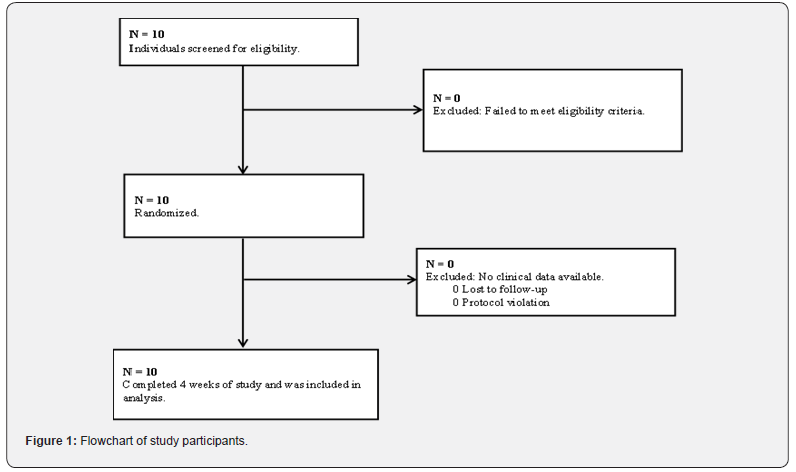

A total of 10 potential participants were screened; ten subjects met all eligibility criteria and were randomized (Figure 1). Five male and five female participants aged 14 to 17 were enrolled in the study. All participants had a European ethnic background and subscribed to the appropriate age educational level at school. Of all, 50% of the participants underwent treatment with CleodermTM, and all participants completed the entire 4-week-long study.

Treatment group 1

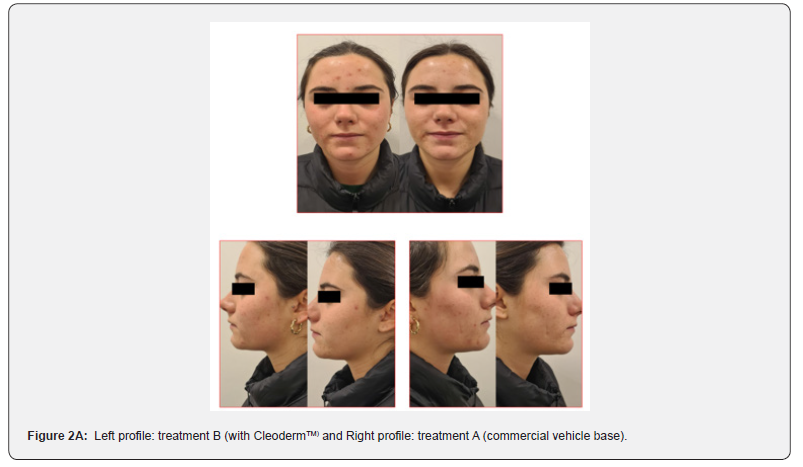

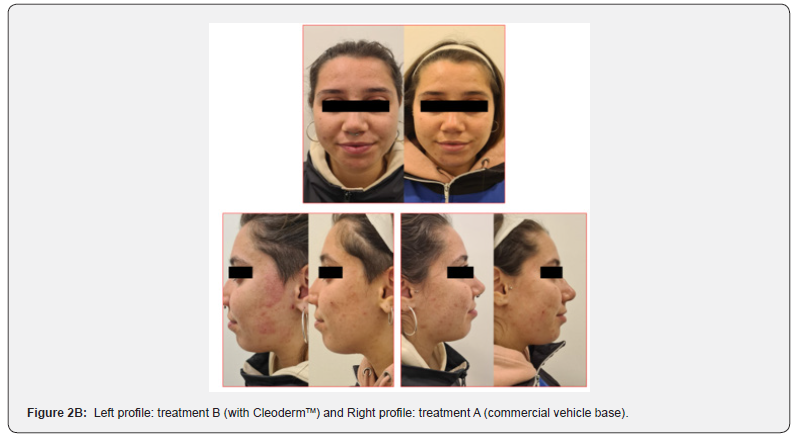

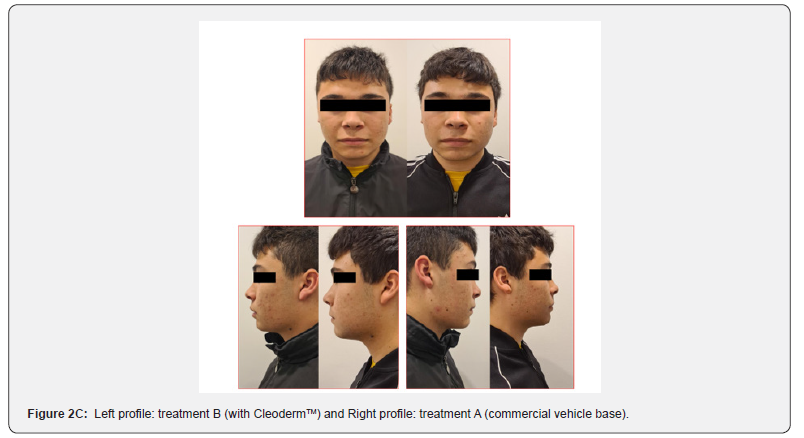

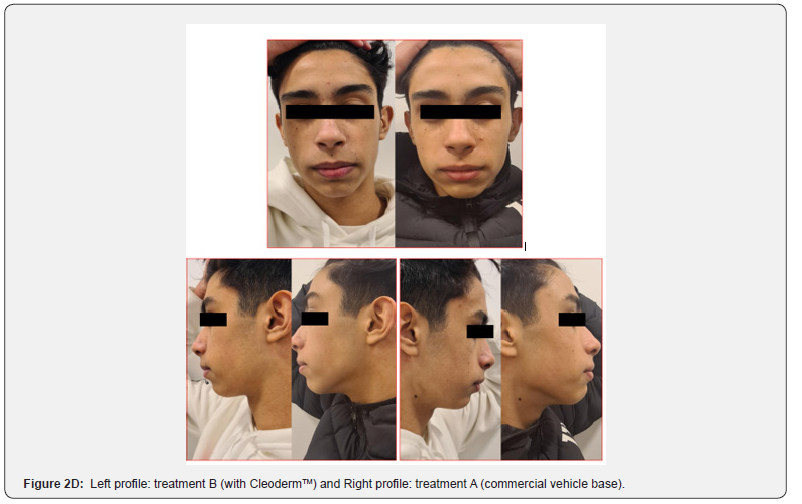

In general, participants reported a decrease in acne severity and the degree of skin oiliness at the end of the study period in treatments A and B. The treatments were well tolerated, and no adverse reactions were reported. However, 80% of the study participants reported increased skin sensitization and discomfort in the hemiface receiving treatment A. The clinical assessment and bilateral facial photographs were performed by a dermatologist at baseline and week 4. Overall, all participants improved their skin outcomes with both treatments at the end of the study. However, in 80% of the study participants, the hemiface receiving treatment B had better outcomes than treatment A (Figure 2A,2B,2C,2D,2E).

Treatment group 2

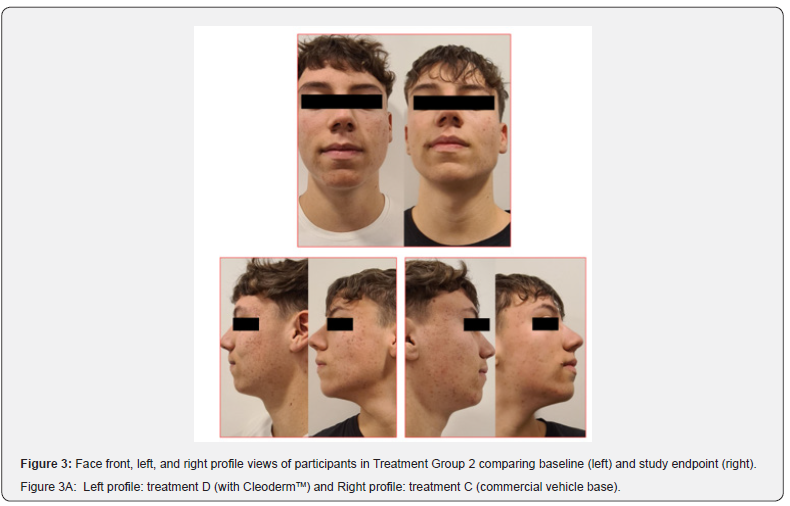

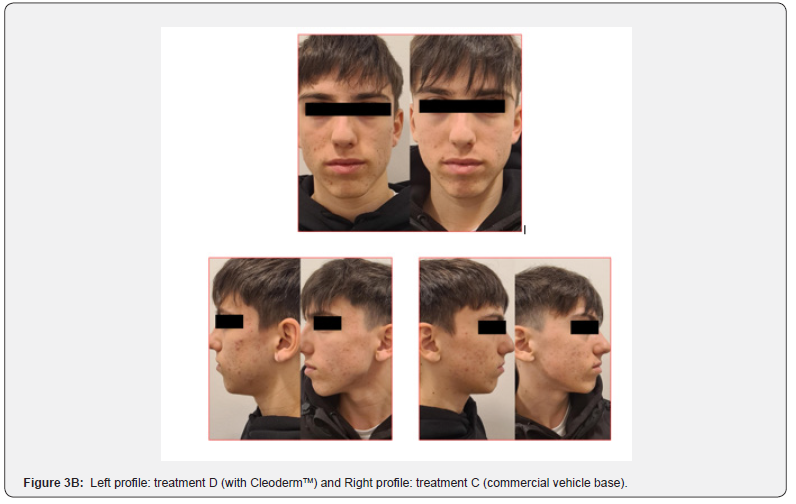

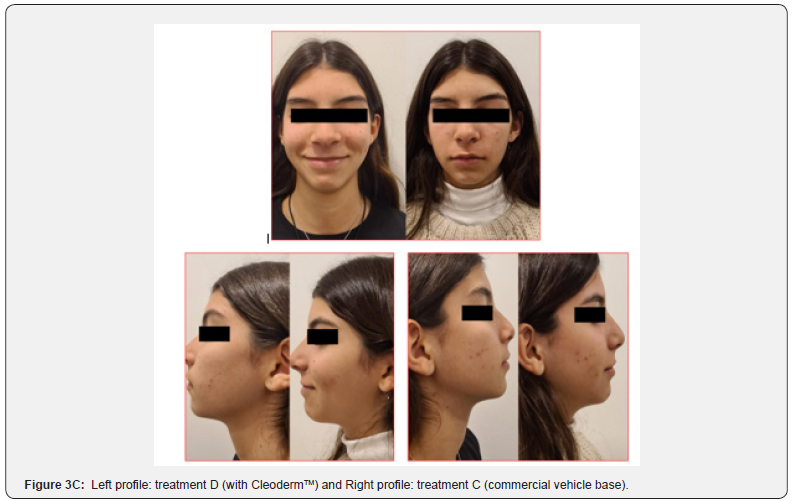

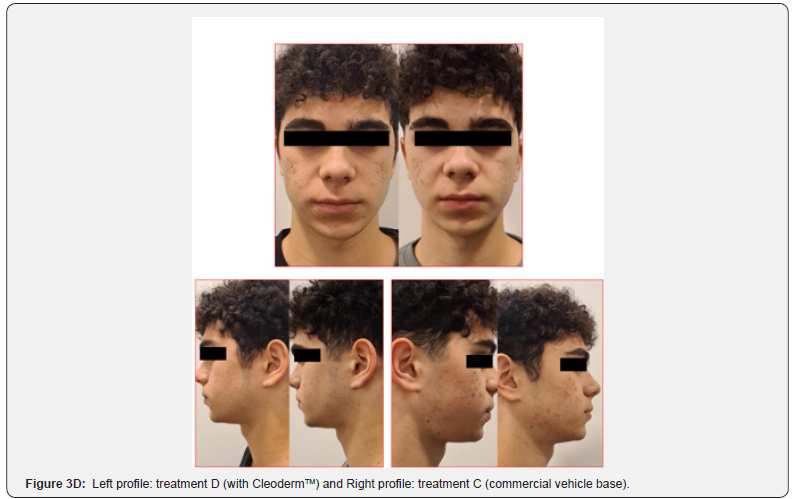

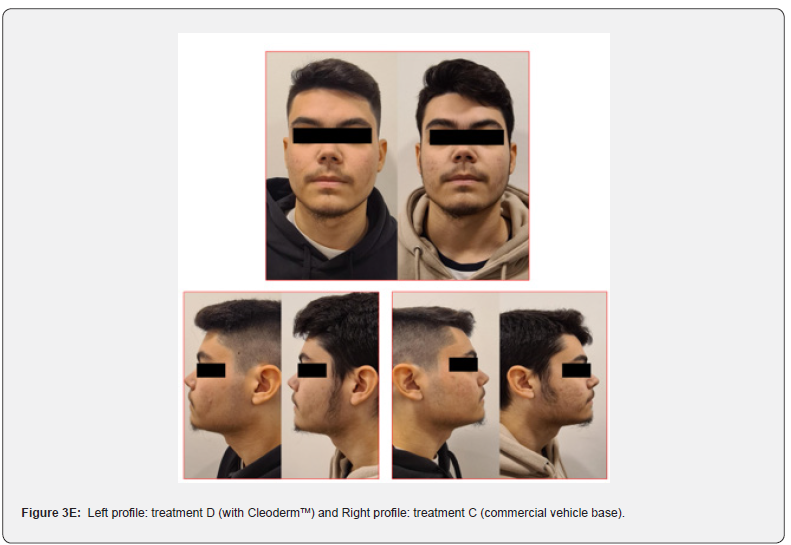

Overall, participants reported a decrease in acne severity and the degree of oiliness of their skin in treatments C and D. The treatments were well tolerated, and no erythema, scaling, and dryness, along with burning or pruritus, were reported. However, 80% of the study participants reported increased mild skin discomfort in the hemiface receiving treatment C. The clinical assessment and bilateral facial photographs showed that baseline Leeds scores for all subjects were similar for treatments C and D. After four weeks, both sides were slightly better (Figure 3, 3A,3B,3C,3D). However, in 80% of the study participants, the hemiface receiving treatment D had better outcomes than treatment C. At the time points studied, no statistically significant differences were noted in sebum production when comparing both treatments.

Discussion

In this randomized, split-face, single-blind clinical trial, all participants showed slightly improved skin outcomes at the end of the treatment phase based on participants’ self-report and dermatologist clinical assessment. However, 80% of the subjects reported increased skin discomfort in the hemiface receiving treatments A and C (with commercial vehicles base), compared to the hemiface receiving treatment B and D, respectively. In addition, in 80% of the study participants, the hemiface receiving treatments B and D (with CleodermTM) had better outcomes than those receiving treatments A and C.

Although adapalene, benzoyl peroxide, and erythromycin have shown clinical efficacy in previous studies, managing patients with acne remains challenging in daily clinical practice [13,17,18,24,25]. Adapalene is a topical retinoid that modulates epidermal growth and differentiation and stimulates humoral and cellular immunity, ideally decreasing cell proliferation and inflammatory response [18,24]. Benzoyl peroxide has bactericidal effects after skin absorption is converted to benzoic acid. In the skin, the residual benzoic acid is metabolized and releases active free-radical oxygen species resulting in the oxidization of bacterial proteins [13,24].

Erythromycin, a topical macrolide antibiotic, effectively reduces inflammatory acne lesions by decreasing the density of Cutibacterium acnes and directly inhibiting neutrophil chemotactic factors and reactive oxygen species production [3,17,25]. However, cutaneous side effects, including dryness, scaling, stinging/ burning, and erythema, have been reported to be associated with these active pharmaceutical ingredients [26,27]. Consequently, patients may exhibit poor adherence to their treatment, leading to inadequate treatment responses. In this context, the vehicle base can significantly influence treatment outcomes by improving efficacy and reducing side effects [28-30]. The vehicle base should promote the adequate percutaneous absorption of different active ingredients and avoid potentially irritating or allergenic components, such as petrolatum, mineral oils, lanolin, perfumes, polyethylene glycol, and fatty alcohols [31]. Therefore, the current study compared the effectiveness (or non-inferiority) and clinical acceptance of CleodermTM, a ready-to-use compounded vehicle, to a commercial vehicle base. The results of this study suggest that CleodermTM might offer a gentler impact on the skin while serving as an adequate vehicle to enhance the efficacy of active ingredients and improve the overall appearance of the skin.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. As it is an exploratory study, the number of subjects and the quantitative parameters measures were limited. However, the results encourage our team to perform a larger clinical assessment.

Conclusion

Both subgroups treated with standard active pharmaceutical ingredients compounded in CleodermTM presented better treatment efficacy and less discomfort. This suggests that compounded topical formulations might be an excellent alternative to personalizing acne treatment.

References

- Diane M Thiboutot, Brigitte Dréno, Abdullah Abanmi, Andrew F Alexis, Elena Araviiskaia, et al. (2018) Practical management of acne for clinicians: An international consensus from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 78(2 suppl 1): 1-23.e1.

- Heng AHS, Chew FT (2020) Systematic review of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Sci Rep 10(1): 5754.

- Afsar FS, Seremet S, Demirlendi Duran H, Karaca S, Mumcu Sonmez N (2020) Sexual quality of life in female patients with acne. Psychol Health Med 25(2): 171-178.

- Lynn D, Umari T, Dellavalle R, Dunnick C (2016) The epidemiology of acne vulgaris in late adolescence. Adolesc Health Med Ther 7:13-25.

- Zaenglein AL, Arun L Pathy, Bethanee J Schlosser, Ali Alikhan, Hilary E Baldwin, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 74(5): 945-973.e33.

- Dagnelie MA, Poinas A, Dréno, B (2022) What is new in adult acne for the last 2 years: focus on acne pathophysiology and treatments. Int J Dermatol 61(10): 1205-1212.

- Jerry K L Tan, Jing Tang, Karen Fung, Aditya K Gupta, D Richard Thomas, et al. (2008) Prevalence and severity of facial and truncal acne in a referral cohort. J Drugs Dermatol 7(6): 551-556.

- Samuels DV, Rosenthal R, Lin R, Chaudhari S, Natsuaki MN (2020) Acne vulgaris and risk of depression and anxiety: A meta-analytic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 83(2): 532-541.

- Cengiz GF, Gürel G (2020) Difficulties in emotion regulation and quality of life in patients with acne. Quality of Life Research 29(2): 431-438.

- Dreno B, Bordet C, Seite S, Taieb C (2019) Acne relapses: impact on quality of life and productivity. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 33(5): 937-943.

- Rapp SR, Steven R Feldman, Gloria Graham, Alan B Fleischer, Gretchen Brenes, et al. (2006) The Acne Quality of Life Index (Acne-QOLI). Am J Clin Dermatol 7(3): 185-192.

- Layton AM, Andrew Alexis, Hilary Baldwin, Vincenzo Bettoli f, James Del Rosso, et al. (2023) Personalized Acne Treatment Tool-Recommendations to facilitate a patient-centered approach to acne management from the Personalizing Acne: Consensus of Experts. JAAD Int 12: 60-69.

- Bikowski J (2010) A review of the safety and efficacy of benzoyl peroxide (5.3%) emollient foam in the management of truncal acne vulgaris. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 3(11): 26-29.

- Munavalli GS, Smith S, Maslowski JM, Weiss RA (2013) Successful treatment of depressed, distensible acne scars using autologous fibroblasts: A multi-site, prospective, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Dermatologic Surgery 39(8): 1226-1236.

- Adalatkhah H, Farhad Pourfarzi, Homayoun Sadeghi-Bazargani (2011) Flutamide versus a cyproterone acetate-ethinyl estradiol combination in moderate acne: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 4: 117-121.

- Polonini HC, Ferreira AO, Brandão MAF, Raposo NRB (2019) Topical monomethylsilanetriol can deliver silicon to the viable skin. Int J Cosmet Sci 41(4): 405-409.

- Bernstein JE, Shalita AR (1980) Topically applied erythromycin in inflammatory acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 2(4): 318-321.

- Shalita A, J S Weiss, D K Chalker, C N Ellis, A Greenspan, et al. (1996) A comparison of the efficacy and safety of adapalene gel 0.1% and tretinoin gel 0.025% in the treatment of acne vulgaris: A multicenter trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 34(3): 482-485.

- Orringer JS, Sewon Kang, Lisa Maier, Timothy M Johnson, Dana L Sachs, et al. (2007) A randomized, controlled, split-face clinical trial of 1320-nm Nd:YAG laser therapy in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 56(3): 432-438.

- Tan J, Andrew Alexis, Hilary Baldwin, Stefan Beissert, Vincenzo Bettoli, et al. (2021) The Personalised Acne Care Pathway-Recommendations to guide longitudinal management from the Personalising Acne: Consensus of Experts. JAAD Int 5: 101-111.

- Layton A, Andrew Alexis, Hilary Baldwin, Stefan Beissert, Vincenzo Bettoli, et al. (2021) Identifying gaps and providing recommendations to address shortcomings in the investigation of acne sequelae by the Personalising Acne: Consensus of Experts panel. JAAD Int 5: 41-48.

- Polonini H, Marianni B, Taylor S, Zander C (2022) Compatibility of Personalized Formulations in CleodermTM, A Skin Rebalancing Cream Base for Oily and Sensitive Skin. Cosmetics 9: 92.

- Polonini H, Zander C, Radke J (2021) CleodermTM Clarifying Cream: A Novel, Topical Vehicle Using Plant-Based Excipients and Actives Targeting Acne and Oily Skin. Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications 11(4): 381-399.

- Tan J, Bissonnette R, Gratton D, Kerrouche N, Canosa JM (2018) The safety and efficacy of four different fixed combination regimens of adapalene 0.1%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel for the treatment of acne vulgaris: results from a randomised controlled study. European Journal of Dermatology 28(4): 502-508.

- Sayyafan MS, Ramzi M, Salmanpour R (2020) Clinical assessment of topical erythromycin gel with and without zinc acetate for treating mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris. Journal of Dermatological Treatment 31(7): 730-733.

- Thiboutot DM, Jonathan Weiss, Alicia Bucko, Lawrence Eichenfield, Terry Jones, et al. (2007) Adapalene-benzoyl peroxide, a fixed-dose combination for the treatment of acne vulgaris: Results of a multicenter, randomized double-blind, controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol 57(5): 791-799.

- Tan J, Gollnick HpM, Loesche C, Ma YM, Gold LS (2011) Synergistic efficacy of adapalene 0.1%-benzoyl peroxide 2.5% in the treatment of 3855 acne vulgaris patients. Journal of Dermatological Treatment 22(4): 197-205.

- Shanmugam S, Rajendran K, Suresh K (2012) Traditional uses of medicinal plants among the rural people in Sivagangai district of Tamil Nadu, Southern India. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2(1): S429-S434.

- Neamsuvan O, Bunmee PA (2016) Survey of herbal weeds for treating skin disorders from Southern Thailand: Songkhla and Krabi Province. J Ethnopharmacol 193: 574-585.

- Fox L, Csongradi C, Aucamp M, du Plessis J, Gerber M (2016) Treatment Modalities for Acne. Molecules 21(18): 1063.

- Hannuksela M, Pat Engasser (1979) Allergic and toxic reactions caused by cream bases in dermatological patients. Int J Cosmet Sci 1: 257-263.