Onychomycosis: Etiopathogenesis and Clinical Characteristics

Ana San Juan Romero1* and Roberto Arenas2

1Mycology graduate student, Mycology Section, “Dr. Manuel Gea González” General Hospital, Mexico

2Dermatologist-mycologist, Mycology Section, “Dr. Manuel Gea González” General Hospital, Mexico

Submission: June 23, 2021; Published: July 02, 2021

*Corresponding author: Ana San Juan Romero, Mycology graduate student, Mycology Section, “Dr. Manuel Gea González” General Hospital, Mexico

How to cite this article: Ana San Juan Romero, Roberto Arenas. Onychomycosis: Etiopathogenesis and Clinical Characteristics. JOJ Dermatol & Cosmet. 2021; 4(2): 555632. DOI: 10.19080/JOJDC.2020.04.555632

Abstract

Onychomycosis is the most common nail disease globally, can occur at any age and is related to persistent trauma of the nail, immunosuppression, hyperhidrosis and other risk factors. Onychomycosis can be caused by dermatophytes, non-dermatophyte molds and yeasts. Recent evidence supports the presence of fungal biofilms that protect them from the immune system as well as antifungal drugs. Biofilm may explain fungal resistance and the inability to eradicate fungal chronic infection. Clinically it presents with onycholysis, nail thickening, brittleness and discoloration. This disease can have a negative and significant effect on the quality of life of patients.

Keywords: Onychomycosis; Risk Factors; Dermatophytes; Nails

Introduction

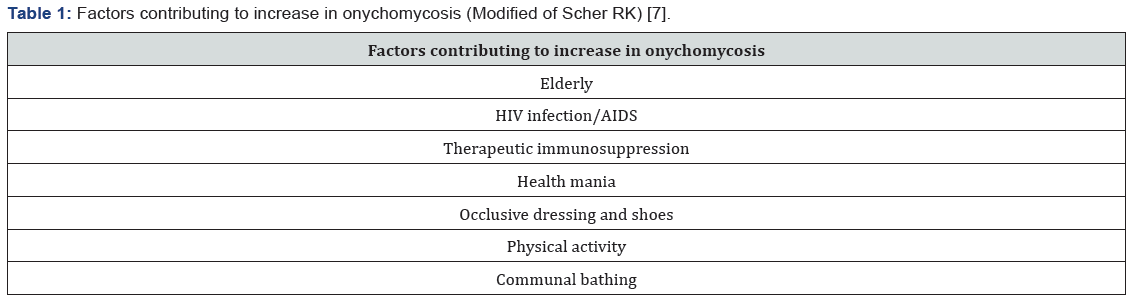

Onychomycosis is the most common nail disease worldwide, accounting for about 90% of toenail and 50% of fingernail infections. The fungal infection leads mainly to discoloration, nail plate thickening and onycholysis [1]. Prevalence increase in the elderly and it reaches all ethnicities with a male predilection (1.5:1) [2,3]. Pediatric cases are increasing, possibly related to childhood obesity and diabetes mellitus [4]. Some known risk factors are the persistent trauma to the nail, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), immunosuppression, hyperhidrosis and smoking. It is also related to the use of occlusive shoes or synthetic material, poor hygiene and the habit of not drying feet skin properly [5,6]. It is now known that there are some factors that favor the increase of fungal infection of the nails (Table 1). These same factors can lead to recurrence of onychomycosis after treatment, which makes it a challenging and chronic disease.

Etiopathogenesis

Onychomycosis can be caused by dermatophytes, non-dermatophyte molds (NDMs) and yeasts. Around 90% of toenail onychomycosis infections are caused by dermatophytes [8]. The most common etiology in Europe are dermatophytes, typically Trichophyton rubrum followed by T mentagrophytes and T interdigitale [9]. In the United States and Mexico T rubrum is the head agent accompanied by T mentagrophytes [10]. Other less frequent tinea unguium infections are caused by Epidermophyton floccosum, Microsporum spp., T violaceum, T verrucosum, T krajdenii, and Arthroderma spp [11]. Candida albicans and C. parapsilosis are isolated between 8 and 10% and are more likely to be causal in fingernails, especially individuals whose hands are frequently immersed in water [11]. NDMs (1-5%) are predominantly Aspergillus spp., Scopulariopsis brevicaulis, Acremonium spp., Fusarium spp. and Neoscytalidium [7,12]. Although dermatophytes are the most common in onychomycosis, NDMs are being reported more frequently in warmer climates [13,14]. Mixed NDMs-dermatophyte infections are uncommon [15]. Recent evidence supports the presence of fungal biofilms. These are microbial communities, rather than acting as independent spores and hyphae, that attach to biological surfaces, such as the nail plate, via an extracellular matrix (ECM) that encases them. The ECM protects them from the immune system as well as antifungal drugs, physical and chemical removal strategies. Dermatophytes, including T rubrum and T mentagrophytes, NDMs including Aspergillus fumigatus and Fusarium spp. and yeast such as C albicans all form biofilms in vitro. Biofilm may be the reason fungal resistance and the inability to completely eradicate fungal chronic infection [16-19].

Clinical Characteristics

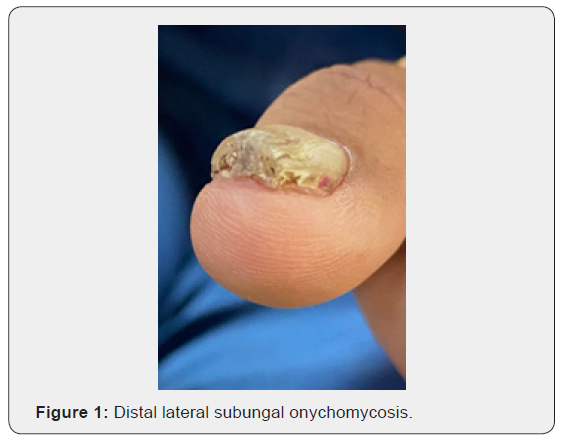

Onychomycosis occurs most often on the feet, with the great toenail most frequently affected. It can present nail separation from the nail bed (onycholysis), nail thickening, brittleness and discoloration (white, yellow or brown). More severe cases may exhibit ingrown nail (onychocryptosis). These symptoms get progressively worse. Dermatophytoma is a fungal mass that presents as yellow, white or brown longitudinal streaks within the nail plate. On the other hand, NDM and yeast infections present usually as yellowish/whitish discoloration [20]. Classification of onychomycosis has five categories established: distal and lateral subungual, superficial white, proximal subungual, endonyx and total dystrophic onychomycosis. Distal lateral subungual infection, the most common form, begins on the distal section of the nail and spreads under the nail bed (Figure 1) [21]. Endonyx is exceptional and involves the nail plate as well as the nail bed. Proximal subungal onychomycosis are less common in the general population, but are the most frequent form in patients with HIV infection and can pose problems because it is more difficult to obtain a good sample for microscopy and culture. White superficial is usually associated with T mentagrophytes rather than T rubrum infection; the sample is relatively simple to obtain and in general has a positive response to topical therapy. Total dystrophic onychomycosis involves the whole nail [22]. Onychomycosis can have a negative and significant effect on the quality of life of patients, both physiologically and emotionally, it can even cause stigmatization and social exclusion. Nail changes can cause pain when walking or standing for long periods, with limited mobility; in addition, it can cause paresthesia, mainly in fingernail onychomycosis. Other negative consequences described are the exacerbation of diabetic foot, acceleration of thrombophlebitis and development of urticaria or dermatophytid reactions [23].

References

- Vlahovic TC (2016) Onychomycosis. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 33(3): 305-318.

- Gupta AK (2000) Onychomycosis in the elderly. Drugs Aging 16(6): 397-407.

- Gupta AK, Gupta G, Jain HC, Lynde CW, Foley KA, et al. (2016) The prevalence of unsuspected onychomycosis and its causative organisms in a multicentre Canadian sample of 30 000 patients visiting physicians’ offices. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV 30(9): 1567-1572.

- Gupta AK, Skinner AR, Baran R (2003) Onychomycosis in children: an overview. J Drugs Dermatol 2(1): 31-34.

- Elewski BE (1998) Onychomycosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 11(3): 415-429.

- Gupta A, Stec N, Summerbell R, Shear N, Piguet V, et al. (2020) Onychomycosis: a review. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 34(9): 1972-1990.

- Scher RK (1996) Onychomycosis: a significant medical disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol 35(3 Pt2): S2-5.

- Haghani I, Shokohi T, Hajheidari Z, Khalilian A, Aghili SR (2013) Comparison of diagnostic methods in the evaluation of onychomycosis. Mycopathologia 175(3-4): 315-321.

- Borman AM, Campbell CK, Fraser M, Johnson EM (2007) Analysis of the dermatophyte species isolated in the British Isles between 1980 and 2005 and review of worldwide dermatophyte trends over the last three decades. Med Mycol 45(2): 131-41.

- Thomas J, Jacobson GA, Narkowicz CK, et al (2010) Toenail onychomycosis: an important global disease burden. J Clin Pharm Ther 35(5): 497-519.

- Ghannoum MA, Hajjeh RA, Scher R, Konnikov N, Gupta AK, et al. (2000) A large-scale North American study of fungal isolates from nails: the frequency of onychomycosis, fungal distribution, and antifungal susceptibility patterns. J Am Acad Dermatol 43(4): 641-648.

- Baran R ed. Baran & Dawber’s (2019) Diseases of the Nails and their Management, 5th Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, USA, ppp. 105-35.

- Raghavendra KR, Yadav D, Kumar A, Sharma M, Bhuria J, et al. (2015) The nondermatophyte molds: emerging as leading cause of onychomycosis in south-east Rajasthan. Indian Dermatol Online J 6(2): 92-97.

- Rafat Z, Hashemi SJ, Saboor AA et al (2019) A systematic review and meta-analysis on the epidemiology, casual agents and demographic characteristics of onychomycosis in Iran. J Mycol Medicale 29(3): 265-272.

- Salakshna N, Bunyaratavej S, Matthapan L, Lertrujiwanit K, Leeyaphan C (2018) A cohort study of risk factors, clinical presentations and outcomes for dermatophyte, non-dermatophyte and mixed toenail infections. J Am Acad Dermatol 79(6): 1145-1146.

- Ramage G, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Lopez RJ (2009) Our current understanding of fungal biofilms. Crit Rev Microbiol 35(4): 340-355.

- Kuhn DM, Ghannoum MA (2004) Candida biofilms: antifungal resistance and emerging therapeutic options. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 5(2): 186-197.

- Costa-Orlandi CB, Sardi JC, Santos CT, Fusco AM, Mendes MJ (2014) In vitro characterization of Trichophyton rubrum and T. mentagrophytes biofilms. Biofouling 30(6): 719-727.

- Mowat E, Williams C, Jones B, McChlery S, Ramage G (2009) The characteristics of Aspergillus fumigatus mycetoma development: is this a biofilm? Med Mycol 47(suppl 1): S120-S126.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK (2015) Onychomycosis: diagnosis and therapy. Medical Mycology: Current Trends and Future Prospects. CRC Press, Boca Raton, USA, pp. 28-57.

- Faergemann J, Baran R (2003) Epidemiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol 149(65): 1-4.

- Seebacher C, Brasch J, Abeck D, Cornely O, Effendy I, Gintyer G, et al. (2007) Onychomycosis. Mycoses 50(4):321-327.

- Cobos Llado D, Fierro Arias L, Arellano Mendoza I, Bonifaz A (2016) La onicomicosis y su influencia en la calidad de vida. Dermatología Cosmética, Médica y Quirúrgica 14(4):318-327.