Treatment of Brittle Nail Syndrome: Systematic Review

Nicola Fiorino Biancardi*

Plastic Surgery at Ivo Pitanguy Institute/ Medicine Master´s Program, Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Submission: April 04, 2021; Published: April 16, 2021

*Corresponding author: Nicola Fiorino Biancardi, MD/MSc - Plastic Surgery at Ivo Pitanguy Institute/ Medicine Master´s Program, Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

How to cite this article: Nicola Fiorino B. Treatment of Brittle Nail Syndrome: Systematic Review. JOJ Dermatol & Cosmet. 2021; 4(1): 555627. DOI: 10.19080/JOJDC.2021.04.555627

Abstract

Background: The Brittle Nail Syndrome combines a series of changes in the composition and structure of the nail bed. The nail is an appendix of the skin, forming part of the integumentary system. Clinical signs of weak nail syndrome, occurs by changes in matrix and deeper layer of nails. This study aims to evaluate current treatments for fragile nail syndrome. Methods: Research was performed by consulting the PubMed, Medline and Bireme databases. The articles were selected by the following generated Mesh term: Brittle [All Fields] AND (“nails” [MeSH Terms] OR “nails” [All Fields] OR “nail” [All Fields]), and “Nails” [Mesh] AND (Review [ptyp] AND “humans” [MeSH Terms]). Results: There is no description of a single effective and predominant treatment. Given these results, we can suggest that information regarding lifestyle, profession and clinical examination represent an impact factor in the diagnosis and treatment of fragile nail syndrome. Conclusion: Although the literature is extensive, constantly updated, there is no standard of treatment for the disease. Individual aspects should be evaluated.

Keywords: Nail; Brittle; Syndrome; Treatment

Introduction

Fragile Nail Syndrome represents a series of changes in the composition and structure of the nail bed [1-4]. Despite presenting a still unspecified etiology, theories point to vascular, physical or traumatic changes for the syndrome, showing similar nail changes, but with different basic etiologies [4]. The nail is composed of a protein called keratin, produced by the horny layer, as modified form the one presented in the hair strands. It can be divided into layers or lamellae, according to superficiality, from top to bottom. The superficial layer is formed by devitalized cells, without nucleus, and with accumulation of keratin. The intermediate layer is the thickest, and has cells with nucleus and extracellular matrix - para-keratinocytic lamina, with less keratin, which gives moisture. The deepest and cranial portion, corresponds to the nail matrix. Composed of germinal tissue that turns into keratin [1,2]. The clinical signs of weak nail syndrome occur by alterations in the matrix and in the deeper layer of the nails. The matrix is equivalent to more than 20% of the nails seen. The nail should show a growth rate of 0.5-1.2 mm / week [5-8]. Histologically, in the cells, the keratin fibrils of the nail plate are arranged in parallel, in order to give the nail hardness. The characteristic of flexibility associated with hardness is due to the connections of the support structures formed by the structure of the intracellular skeleton, the proteins associated with keratin - forming a matrix between the keratin filaments, the lipid bilayer - preventing dehydration, and desmosomes [9-11]. Several factors - intrinsic, chemical, environmental - can alter the connections that give nail hardness, leading to Fragile Nail Syndrome. Secondary disorders that alter vascularity and promote inflammation can alter nail growth. Environmental factors - such as professions with exposure to chemicals, or exposure to radiation can be the cause of frailty. The causes of nail changes are identified by research protocols that help the professional, through the presented semiological characteristics, to institute the correct treatment for each change [4].

Methods

Systematic Literature Review. Performed by consulting the PubMed, Medline and Bireme databases. The articles were selected by the term Mesh: (Brittle [All Fields] AND (“nails” [MeSH Terms] OR “nails” [All Fields] OR “nail” [All Fields]))] AND “humans” [MeSH Terms]). The data were tabulated and presented as to their results. The research did not have time as a limiting factor for clinical trials

Result

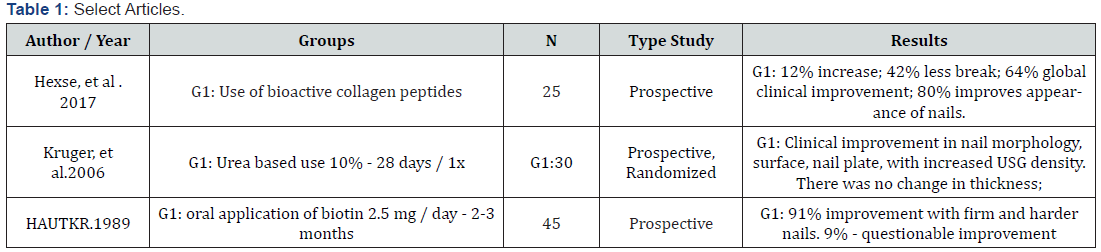

After selecting the articles, their results were tabulated in (Table 1). The correct treatment of nail fragilities is directly related to the semiological characteristics of the nails and the characteristics observed. The identification of factors, such as professional activity, daily activities related to the use of hands, and the complete clinical examination with armed propedeutics, in order to identify diseases that have manifestations in the nails. The predominance of the semiological pattern Onicosquizia or Onicorrexe is extremely important to guide the treatment. There is no description of a single effective and predominant treatment. Biotin, a water-soluble vitamin B, present in food sources, such as nuts, peanuts, milk, in humans, it was found that their oral intake at a dose of 2.5 mg / day of biotin, proved to be a factor for improving nails. Hautkr carried out a study evaluating the use of oral biotin for the treatment of nail fragility. It obtained an important result, with significant improvement. The review of articles proposed by Lipner, et al. 2018; evaluating the oral use of biotin, showed that the researched clinical trials showed that biotin increased the firmness, hardness and appearance of the nail. The dose used in the studies described was 2.5 mg / day. Other studies show improvement with the use of biotin at a dose of 2.5 mg for 6-12 months, in 67% of cases [12]. The study proposed by Hexse, et al. 2017, using oral treatment of Fragile Nail Syndrome, in 25 female patients aged 18-50 years, showed significant nail improvement, using Bioactive Collagen Peptives (BCP -Verisol) , and reduction of nail breakage. In cases of nails with an onychoschizic pattern, due to their lamellar division, treatment with topical actives that promote humidification or excessive dehydration should be avoided. As with trauma, the use of irritating substances can cause inflammation of the bed and worsen growth. Krüger, et al. 2005, showed improvement in the aesthetic appearance and increase in nail density with the use of 10% Urea Base, in nails of 30 patients, when compared to placebo. The research was carried out with the same patients, in which one hand was applied based on urea, and in the other placebo. In the case of Onychorrhexis, the search for metabolic and nutritional diseases must be done through physical examination, and laboratory tests, in order to identify secondary factors. Topical agents to strengthen the nail should be used with caution, as they can cause inflammatory reactions adjacent to the bed and the Eponychium. Such as the use of formaldehyde, which can cause adjacent dermatitis, in addition to bluish coloring of the nail, and onycholysis. Other treatments are described as vitamin replacements and oral iron. However, they do not present scientific evidence and proof of results [13-17].

Conclusion

In view of these results, we can suggest that the information regarding lifestyle, profession and clinical examination, represent an impact factor in the diagnosis and treatment of Fragile Nails syndrome. Although the literature is a broad, constantly updated, there is no standard of treatment for the disease. Individual aspects should be assessed.

References

- Berker D (2013) Nail anatomy. Clin Dermatol 31(5): 509-515.

- Andrè J, Sass U, Richert B, Theunis A (2013) Nail pathology. Clin Dermatol 31(5): 526-539.

- Tosti A, Piraccini B. Chapter 89. Biology of Nails and Nail Disorders.

- Van de Kerkhoff, Pasch MC, Scher RK, Kerscher M, Gieler U, et al. (2005) Brittle nail syndrome: a pathogenesis base approach with proposed grading system. J Am Acad Dermatol 53(4): 644-652.

- Lubach D, Cohrs W, Wurzinger R (1986) Incidence of brittle nails. Dermatologica 172(3):144-147.

- Scher RK (1989) Brittle nails. Int J Dermatol 28(8): 515-516.

- Norton LA (1971) Incorporation of tymidine-methyl-H3 and glycine2-H3 in the nail matrix and bed of humans. J Invest Dermatol 56(1): 61-68.

- Kechijian P (1985) Brittle fingernails. Dermatol Clin 3(3): 421-429.

- Samman PD, Fenton DA (1986) The nails in disease. 4th ed, Heinemann, UK, pp. 14-16.

- Walters KA, Flynn GL, Marvel JR (1981) Physiochemical characterization of the human nail: I. Pressure-sealed apparatus for measuring nail plate permeabilities. J Invest Dermatol 76(2): 76-79.

- Fleckman P (1997) Basic science of the nail unit. In: Scher RK, Daniel CR (Eds.), B Nails: therapy, diagnosis, surgery. 2nd ed, Saunders, USA, pp. 48.

- Rycroft RJG, Baran R (2001) Occupational abnormalities and contact dermatitis. In: Baran R, Dawber RPR (Eds.), Diseases of the nails and their management. 3rd ed, Blackwell, Oxford, UK, pp. 1-79.

- Nandedkar M, Scher K (2005) An update on disorders of the nail. J Am Acad Dermatol 52: 877-887.

- Finlay A (1980) An assessment to factors influencing flexibility of human fingernails. Br J Dermatol 103(4): 357-365.

- Elewski B (1997) The effect of toenail onychomycosis on patient quality of life. Int J Dermatol 36(10): 754-756.

- Drake LA, Patrick DL, Fleckman P, Andr J, Baran R, et al. (1998) The impact of onichomycosis on quality of life: development of an international quetionaire to measure patient quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol 41(2): 189-96.

- Scher R (1994) Onichomycosis is more than a cosmetic proplem. Br J Dermatol 130: 15.