Atypical Presentations of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Real Diagnosis Challenge

Salem Bouomrani*

Department of Internal medicine, Military Hospital of Gabes, Tunisia

Submission: June 22, 2020;Published: July 06, 2020

*Corresponding author: Salem Bouomrani, Department of Internal medicine, Military Hospital of Gabes, Tunisia

How to cite this article: Salem Bouomrani. Atypical Presentations of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Real Diagnosis Challenge. JOJ Dermatol & Cosmet. 2020; 3(2): 555607. DOI: 10.19080/JOJDC.2020.03.555607

Abstract

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is an infectious dermatosis caused by a parasite (Leishmania spp) and transmitted to humans by the bite of a female sandfly (Phlebotomus spp). It is still endemic in more than 100 countries, representing an important public health problem worldwide. The clinical presentations of this disease are very polymorphic and sometimes very difficult to diagnose. Nearly 17 clinical variants of CL qualified as “atypical” or “unusual” were described; their prevalence is estimated at 2-5% of all CL. As rare as they are, these atypical clinical presentations of CL deserve to be well known by clinicians, particularly those in first line consultations and in endemic areas.

Keywords:Cutaneous Leishmaniasis; Unusual Presentation; Atypical Presentation; Lupoid; Psoriasiform; Erysipeloid; Zosteriform

Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a vector-borne disease with a large spectrum of clinical features ranging from localized cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) to generalized systemic visceral disease [1-3]. It is caused by parasites of the genus Leishmania and transmitted to humans through the bite of a female phlebotomine sandfly [1-3]. Chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis (CCL) is the most frequent of the three clinical subtypes of this disease (cutaneous, muco-cutaneous, and visceral leishmaniasis) [1-3]. It is still endemic in almost 100 countries around the world, and according to the World Health Organization (WHO), 12 to 15 million people are infected, 350 million are at risk of acquiring the disease, and 1.5 to 2 million new cases are recorded annually [1,4]. The clinical presentations of CL are very polymorphic and sometimes very difficult to diagnose.

Typical clinical presentation of CL

Pure CCL was first described in 1876 by Lewis and Cunningham in the Middle East with its characteristic ulcero-crusted nodular lesion, hence the old names of “Orient button”, “Aleppo button”, and “Jericho button” [1]. Subsequently, the disease was described in the Mediterranean basin and particularly its southern shore, hence the classic names of “button of Gafsa” (Tunisia) and “button of Biskra” (Algeria). These lesions are caused mainly by four species of leishmaniasis: L. major, L. infantum, L. tropica, and L. kiliki, and define the old world leishmaniasis (Middle East, Mediterranean basin, Africa, Asia, and India) [1-6]. Depending on the species of leishmaniasis responsible for the infection, the geographic classification opposes leishmaniasis of the old world to that of the new world (Central and South America), mainly caused by L. mexicana, L. amazonensis, and L. braziliensis [1,4] (Figure 1).

Atypical clinical presentation of CL

Because of their uncommon shape or site, theses clinical presentations of CL are qualified as “atypical” or “unusual”, and authors estimated their prevalence at 2-5% of all CL [7-11]. Nearly 17 atypical variants of CL have been described: lupoid, sporotricoid, eczematiform, verrucous, dry, zosteriform, erysipeloid, psoriasiform, pseudotumoral, discoid lupus-like, squamous cell carcinoma-like, erythematous volcanic ulcer, acute paronychial, chancriform, palmoplantar, lip, and annular forms [7- 11] (Figures 2 & 3).

Physiopathology of atypical CL

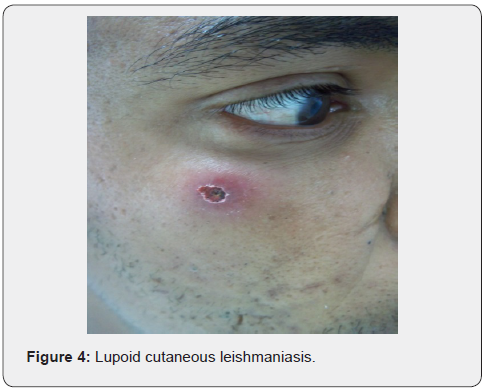

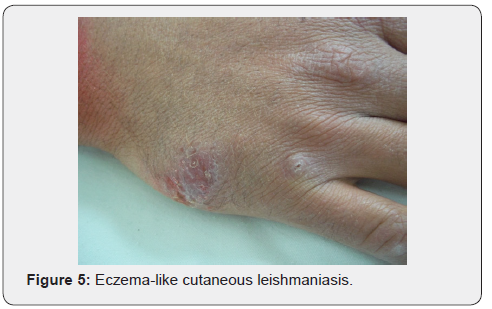

The exact pathophysiology of these atypical presentations is not yet fully understood; they are particularly frequent in immunocompromised subjects and the alteration of the host’s immune response seems to have a primary role in their development [10,11] (Figures 4 & 5).

Diagnosis of atypical CL

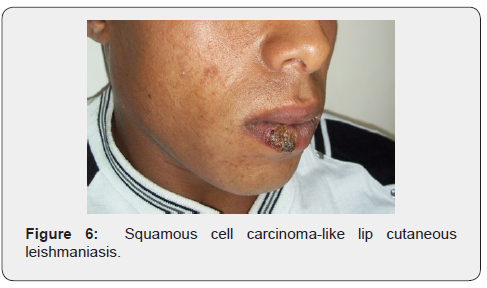

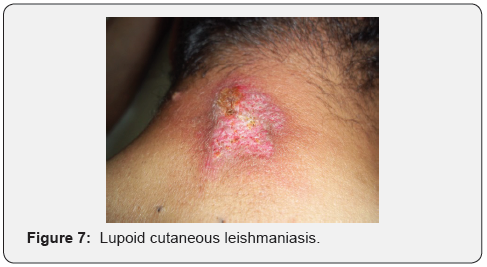

The diagnosis of CL in front of these forms may be overlooked even in endemic areas [8-11], and patient can mistakenly be treated for other diagnosis in several occasions. Dermoscopy can be very helpful for the diagnosis of this atypical variant of CL [8- 11]. The diagnosis of CL is confirmed by microscopic examination of stained tissue-scraping smears from these lesions revealing the presence of Leishmania amastigotes (Figures 6 & 7).

Differential diagnosis of atypical CL

The differential diagnosis of unusual/atypical CL is mainly made with lupus vulgaris (cutaneous tuberculosis), lupus erythematosus, lupus pernio (form of cutaneous sarcoidosis), erysipelas, eczema, psoriasis, fungal infections, granulomatous cheilitis, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, orofacial granulomatosis, Wegener granulomatosis, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and foreign body reaction depending on the clinical aspect and the location of the lesion [8- 11] (Figure 8).

Treatment and prognosis of atypical CL

Atypical CL can be successfully treated with systemic or intralesional injections of meglumine antimoniate, and its prognosis is usually favorable. In case of resistance to conventional treatment, association of meglumine antimoniate, allopurinol, and cryotherapy can be proposed [8-11] (Figure 9).

Conclusion

As exceptional and unusual as they are, these atypical forms of CL deserve to be well known by clinicians, particularly those in the first line and in endemic countries.

References

- Torres-Guerrero E, Quintanilla-Cedillo MR, Ruiz-Esmenjaud J, Arenas R (2017) Leishmaniasis: a review. F1000Res 6: 750.

- Meireles CB, Maia LC, Soares GC, Teodoro IPP, Gadelha MDSV, et al. (2017) Atypical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis: A systematic review. Acta Trop 172: 240‐254.

- Galluzzo CW, Eperon G, Mauris A, Chappuis F (2013) Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Rev Med Suisse 9(385): 990‐995.

- Burza S, Croft SL, Boelaert M (2018) Leishmaniasis. Lancet 392(10151): 951-970.

- Mokni M (2019) Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Ann Dermatol Venereol 146(3): 232‐246.

- Burnett MW (2015) Cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Spec Oper Med 15(1): 128‐129.

- Hengge UR, Marini A (2008) Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Hautarzt 59(8): 627‐632.

- Raja KM, Khan AA, Hameed A, Rahman S (1998) Unusual clinical variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Pakistan. Br J Dermatol 139(1): 111-113.

- Bari A, Rahman SB (2008) Many faces of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 74(1): 23-27.

- Nasiri S, Mozafari N, Abdollahimajd F (2012) Unusual Presentation of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Lower Lip Ulcer. Arch Clin Infect Dis 7(2): e13951.

- Shamsuddin S, Mengal JA, Gazozai S, Mandokhail ZK, Kasi M, et al. (2006) Atypical presentation of cutaneous leishmaniasis in native population of Baluchistan. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 16: 196-200.