Mid Aortic Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of the Literature

Sarah Khalid1*, Saima Shan2, Jovaria Ehsan3, Aisha Hameed3 and Pakeeza Shafique4

1Post Graduate Trainee Radiology, Federal Government Polyclinic Hospital, Islamabad

2Head of Radiology Department, Federal Government Polyclinic Hospital, Islamabad

3Associate Radiologist, Federal Government Polyclinic Hospital, Islamabad

4Assistant Professor of Radiology, Northern Border University, Saudi Arabia

Submission: December 31, 2025;Published: January 12, 2026

*Corresponding author:Dr. Sumaira Sadeed, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, AMU, Aligarh, India

How to cite this article: Sarah Khalid, Post Graduate Trainee, Radiology Federal Government Polyclinic Hospital, Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, 44 Luqman Hakeem road, G-6/2, Islamabad, Pakistan. DOI: 10.19080/JOJCS.2026.15.555924.

Keywords: Keywords:Abdominal aorta; Ostial stenosis; Mid-aortic-syndrome; Echocardiography; Fibromuscular dysplasia; Hypertension; Endovascular

Introduction

The segmental narrowing of the proximal branches of abdominal aorta and ostial stenosis of the major branches leads to a condition called Mid-aortic syndrome (MAS). It is typically a disease of adulthood but can present in children where it poses a great challenge for the clinicians and the patient [1]. The common use of the aortography in the diagnosis of mid-aortic-syndrome has no harmful effects and provides great safety quotient also enables the diagnosis of the condition relatively less demeaning. However, the pathogenesis involved behind the syndrome is often unclear [2]. Refractory hypertension is the commonest presentation in the patients suffering from Mid-Aortic-Syndrome (MAS). Other less common signs and symptoms which appear as the disease progresses include intermittent claudication, renal insufficiency, congestive cardiac failure and end organ failure due to hypertension. Less frequent terms referred for the syndrome include hypoplasis, coarctation of abdominal aorta or subisthmic coarctation which signifies congenital cause. The main focus of the treatment is to resolve the hazardous effects from the hypertension if and when they develop and hypertension in general and prevent the renal impairment. Among the many treatment options available the most widely used is suitable antihypertensives, percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty (PTRA) and/or stent implantation where available, surgical revascularization under skilled conditions and unilateral nephrectomy in advanced cases. This is the first ever case reported in the Federal Government Polyclinic Institute, Islamabad [3].

Case Report

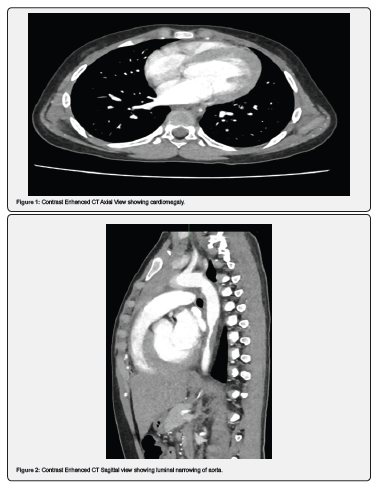

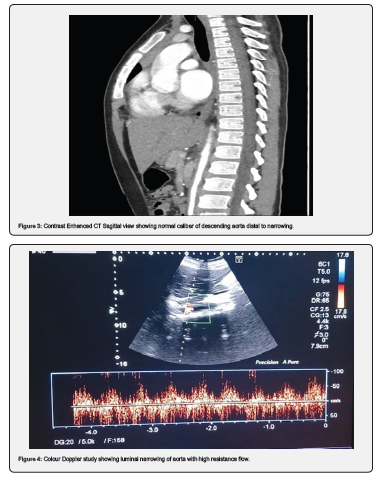

A 11-year-old girl reported to the ENT department of Federal Government Polyclinic Hospital, Islamabad, with complaints of intermittent headaches for one year and epigastric discomfort. Examination revealed elevated blood pressure with a systolic over diastolic value of 210/130mm Hg, and disproportionate blood pressure in bilateral upper and lower limbs. She was referred to the pediatric department, where preliminary tests showed a normal complete blood count but a lipid profile with elevated triglycerides (261mg/dL). Echocardiography performed by a pediatric cardiologist suggested severe abdominal coarctation (Figure 1-3).

Investigations

She was then referred to the radiology department for a CT aortogram, which showed marked concentric narrowing of the descending thoracic aorta from the T6 to T9 vertebral bodies, with circumferential mural thickening at the T7 vertebra. The aorta returned to normal caliber distally to the T10-T11 level, with noted intimal thickening at the aortic hiatus along its lateral wall. There was also extension of intimal thickening into the abdominal aorta, its major branches, and bifurcation, though these branches were of normal caliber distally. Mild cardiomegaly with left-sided cardiac chamber enlargement was noted. Based on these findings, mid-aortic syndrome was suggested. The patient had experienced multiple episodes of headache and epigastric discomfort but had not been previously investigated or diagnosed. After proper investigations and diagnosis, the patient has been referred to the pediatrics vascular department for the treatment purpose (Figure 4).

Discussion

It has been frequently observed that in the congenital heart diseases; particularly secondary dilated cardiomyopathies, coarctation of aorta is the frontline cause. The effective and timely diagnosis based on the sign symptoms can prevent the progression of disease to harmful cardiomyopathy. The effective and efficient physical examination which includes simultaneous palpation of pulses in both the upper and lower extremities pave the way for timely diagnosis. The condition depicting weak femoral but strong brachial pulses should always raise the suspicion of coarctation of aorta. Hence the baseline examination of the blood pressure and pulses of both the upper and lower limbs proves quite beneficial in the timely diagnosis [4].

Our patient was a child with undiagnosed congenital condition at the time of presentation. A similar study conducted at Memorial Hermann Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine was a cohort from year 1997 till 2018 which included 13 patients. It was designed to study the predisposing conditions behind the occurrence of mid-aortic-syndrome. It revealed strong association with the congenital condition such as Takayasu which was found in 1 subject out of 13, neurofibromatosis type 1 which occurred in 2 out 12 cases, Williams syndrome which had its predisposition in 1 out of 13 subjects and fibromuscular dysplasia associated in 2 cases out of 13. The study also revealed the primary anatomic site which were suprarenal and infrarenal aorta. The extra-aortic sites involvement included occurrence in renal artery (4/13), superior mesenteric artery (3/13) and celiac artery (3/13). The clinical signs and symptoms of study revealed that all the 13 subjects presented with hypertension, 9 with claudication and only 5 with postprandial abdominal pain [5].

Another study conducted on the anatomical involvement and clinical presentation of the signs and symptom from Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ; Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ; and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Cincinnati, OH, revealed that 97% of the subjects showed segmental or diffuse narrowing of the abdominal aorta, 66.2% had renal artery involvement, superior mesenteric artery was involved in 29.5% of the subjects, celiac artery was compromised in 22.4% and only 3% showed involvement of thoracic aorta [6]. Another pediatric cohort study on 8 patients revealed the median age at which mid-aorticsyndrome was diagnosed was 2.6 years and the median followup age was 8.6 years. Hypertension presented in six patients, one patient presented with cardiac symptoms of heart murmur and one with the symptoms of cardiac failure. The 8 pediatric patients were treated with the antihypertensive drugs. Seven out of 8 patients were treated on lines of endovascular plan and only one had to undergo surgery. By the time the cohort ended, six pediatric patients treated on the lines of endovascular procedure only 2 achieved good blood pressure control later, one had an acceptable blood pressure reading, one each suffered from stage 1 and stage 2 hypertension. The follow up revealed death of one pediatric subject. Hence these studies strongly suggest if timely diagnosis of MAS is to be achieved then regular monitoring of the blood pressure has to be ensured [7].

Conclusion

Among the many but significant cause of hypertension in pediatric cases, young people are mid-aortic-syndrome with strong association with congenital conditions, renal artery stenosis and visceral artery stenosis. The management plan depends upon the percentage of stenosis of abdominal aorta. If the involvement is beyond 60% then conservative management must be avoided and invasive plan must be followed. Endovascular treatment option in the pediatric cases has proved to be beneficial in managing the stenosis initially however sustainable results are not achievable. If the endovascular or antihypertensive treatment plan fails to maintain the blood pressure control in the pediatric cases then the surgical options must be explored for achieving better results, especially when the child is able to accommodate an adequately sized graft and show better results. A multidisciplinary approach and regular follow-up are crucial to monitor for recurrent hypertension and end-organ damage.

References

- Panayiotopoulos YP, Tyrrell MR, Koffman G, Reidy JF, Haycock GB, et al. (1996) Mid-aortic syndrome presenting in childhood. British Journal of Surgery 83(2): 235-240.

- Sen PK, Kinare SG, Engineer SD, Parulkar GB (1963) The middle aortic syndrome. Br Heart J 25(5): 610-618.

- Lin YJ, Hwang B, Lee PC, Yang LY, CC Laura Meng (2008) Mid-aortic syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. International Journal of Cardiology 123(3): 348-352.

- Alehan D, Kafalı G, Demircin M (2004) Middle aortic syndrome as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Department of Pediatric Cardiology and Department of Thorax and Cardiovascular Surgery, Hacettepe University, Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey. Published in Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 4: 178-180.

- Patel RS, Nguyen S, Lee MT, Price MD, Krause H, et al. (2020) Clinical Characteristics and Long-Term Outcomes of Midaortic Syndrome. Annals of Vascular Surgery 66: 318-325.

- Zurcher K, Towbin R, Schaefer C, Jorgensen S, Towbin A (2021) Pediatric Radiological Case. Middle Aortic Syndrome.

- Garcia LB, Prada H, Sainz AL, de-Toledo JS, Manuel J (2022) Mid-aortic Syndrome in a Pediatric Cohort. Pediatric Cardiology 44(1): 168-178.