Showing Symptoms is not Enough: A Case Study on Identifying, Intervening and Mitigating Postpartum Depression

Kylie Campbell-Clarke*

University of Otago, New Zealand

Submission: March 09, 2024; Published: March 22, 2024

*Corresponding author: Kylie Campbell-Clarke, BBA, MBus, University of Otago, New Zealand, Email ID: camky847@student.otago.ac.nz

How to cite this article: Kylie Campbell-C. Showing Symptoms is not Enough: A Case Study on Identifying, Intervening and Mitigating Postpartum Depression. JOJ Case Stud. 2024; 14(4): 555894 DOI: 10.19080/JOJCS.2024.14.555894.

Abstract

Problem: This case study examines a mother’s (Winnie) struggle with postpartum depression, underscoring the urgency for effective identification, mitigation, and intervention strategies to minimize its impacts.

Background: Postnatal depression is a global priority, urging healthcare systems and governments to establish guidelines for effective perinatal mental health care. Canada's absence of a national strategy exacerbates systemic issues, as shown in this case study.

Aim: This paper endeavors to address these systemic deficiencies by proposing comprehensive strategies to integrate into the framework of postpartum care.

Methods: The case study methodology provides a comprehensive analysis of a specific case or phenomenon within its real-life context, making it well-suited for this research paper.

Findings: Counselling, support from indirect providers like pediatricians, and effective screening for postpartum depression would best meet mothers' needs.

Discussion: Despite challenges like fragmented records and limited collaboration, addressing postpartum depression is feasible. This study highlights early risk factors and suggests that timely identification and intervention could benefit both mother and infant health. Pediatricians, underutilized for PPD, could play a vital role in identification and intervention. Lack of routine screening and follow-up worsens under identification and under treatment in Canada's perinatal mental health care system, hindering comprehensive care for mothers like Winnie.

Conclusion: The suggestions for after birth counselling, indirect provider training (e.g. pediatricians), early and regular postpartum depression screening, effective follows up and referrals to psychiatry for mothers can be implemented now.

Keywords: Postnatal; Depression; Traumatic birth; Referral systems

Introduction

Postnatal depression stands as a formidable global health challenge, yet within Canada's perinatal healthcare system, a troubling fragmentation persists. Lacking a cohesive national perinatal mental health care strategy or standardized guidelines, as highlighted by both the Public Health Agency of Canada [1] and the Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario [2], the current landscape leaves healthcare practitioners tangled within silos, impeding their ability to systematically identify and intervene in the onset and progression of postpartum depression among mothers.

This paper endeavors to address these systemic deficiencies by proposing comprehensive strategies to integrate into the framework of postpartum care. Through the lens of a compelling case study featuring Winnie, and informed by a synthesis of best practices, literature recommendations, and empirical research, we aim to elucidate the systemic gaps in care and offer actionable solutions to bridge them.

Central to our discussion is the recognition that the existing system fails to facilitate integration and collaboration, lacking mechanisms for shared records and continuity of care. Nonetheless, amidst these challenges lie opportunities for healthcare practitioners to enhance their proficiency in identifying, intervening, and mitigating postpartum depression. To this end, our recommendations encompass empowering indirect care providers, such as pediatricians, with the necessary tools and knowledge to play a pivotal role in early detection and intervention. Furthermore, we advocate for the establishment of hospital standards mandating post-birth counseling, particularly in cases of traumatic births, to ensure comprehensive support for mothers during this vulnerable period.

Methodology

Case study methodology is a research approach that involves in-depth examination and analysis of a particular case, situation, or phenomenon within its real-life context [3]. Its capacity to offer profound insights into complex phenomena renders it particularly suitable for this research paper [4]. By delving into the intricacies of a case involving postpartum depression, this methodology facilitates a nuanced understanding of the subject matter. Through a contextual lens, it enables researchers to explore the multifaceted aspects of postpartum depression within the framework of real-life situations. Moreover, the holistic perspective and adaptable nature of case study methodology foster research reflexivity and deepen insights, especially when examining phenomena within ethnographic cultures. Through this approach the researcher hopes to reflect on a semi-real-life scenario using aspects of her own experience to help qualify the findings of this study.

Case Study

A mother, Winnie, 35, had a traumatic vaginal delivery of a 9lbs baby whom she decides to exclusively feed with formula. Winnie had never shown any signs or symptoms of depression, anxiety, or other mental health concern before or during pregnancy. At the hospital, no Postpartum Depression (PPD) screening is conducted as it is not standard protocol, her mental status is unknown and unchecked following the birth and discharge.

The baby is a difficult baby that appears colicky and may be showing signs of ‘purple crying’. Winnie had been exhibiting signs of uncontrolled weeping and exhaustion at home. She felt sad, possibly depressed, but was not proactive in dealing with it because it is just the ‘baby blues’, and she could not focus on herself with a highly demanding baby.

Prior to the standard first postpartum follow up visit with the maternity doctor, at one week postpartum the baby has blood in its stool and the doctor refers the baby immediately to the pediatrician. The pediatrician diagnoses the baby with a cow’s milk allergy and notifies Winnie to place the baby on hypoallergenic formula. Winnie is asked briefly about her how she is doing and is visibly miserable with her manner and presentation, but nothing is followed up with Winnie. An appointment is made for the baby in a week if needed pending any urgent needs prior to that time.

At the first postpartum visit with the maternity doctor, the baby is no longer having blood in its stool (one day after pediatrician visit on new hypoallergenic formula). After the checks of the baby, the doctor notes that Winnie is very sad, but not a harm to herself or the baby. No referral or follow up is required until the next appointment in six weeks postpartum.

Between the two standard postpartum visits from the maternity doctor, the pediatrician has resolved the blood in stool issue, but the infant still appears to have excessive crying. However, this is ‘typical’ for infants at this age and Winnie is told that the infant will outgrow such a condition, it just takes time. During this time, Winnie becomes increasingly exhausted from lack of sleep, isolated while caring for a demanding infant, and experiencing depression.

At the six-week postpartum visit with the maternity doctor the baby is still colicky and ‘purple cries’, but overall is in good health. Winnie is clearly exhausted and extremely upset. The maternity doctor advises her to use the government-led programs and not for profits to meet other mothers and get some support. These programs require Winnie to either complete forms and wait or initiate the contact necessary to use the programs, which take time. Winnie already struggles to leave the house with the baby.

At two months postpartum, the baby’s first vaccinations at the local health centre are available for use. Although the appointment is directed at the infants weighing, measuring, overall health and vaccinations, Winnie is provided with her first PPD screening using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EDPS). While the nurse is obtaining the necessary vaccinations out of the room, Winnie, while holding her screaming baby, completes the form. After the vaccinations are completed, the nurse reviews the form and advises Winnie that she is required to go to the Emergency Department (ED) because her score was so high on the EDPS.

At the ED, Winnie admits to the ED doctor to having suicidal ideation. Winnie is provided a prescription for medication and is referred to psychiatry for the support of her PPD screening and diagnosis.

Two weeks pass and Winnie receives a call for her psychiatry appointment. During her psychiatry appointment she is officially diagnosed with PPD and started on a medication routine to minimize the impact to her health and counselling. It takes time but the medication and counselling help.

Findings

Counselling services offered to mothers following traumatic birth experiences would significantly contribute to maternal psychological well-being and coping mechanisms. Feeling more supported, understood, and equipped to manage postnatal challenges after engaging in counselling sessions would benefit all mothers. Furthermore, indirect care provided by pediatricians, including routine check-ups and proactive monitoring of maternal and neonatal health, could play a crucial role in early detection and intervention for potential postnatal complications. Pediatricians' involvement can foster a sense of reassurance among mothers and facilitate timely access to specialized care when needed.

Moreover, the implementation of a screening system with actual follow-up and referral mechanisms could demonstrate promising results in identifying at-risk mothers and newborns for timely interventions. The potential screening system could enable healthcare providers to proactively address maternal and neonatal health concerns, leading to improved outcomes and reduced long-term sequelae. However, challenges such as resource constraints and coordination among healthcare professionals are identified as barriers to the effective implementation of screening protocols.

Discussion

There were multiple risks factors present early on in this case and the presentation of the participant’s PPD could have been identified, intervened, and mitigated earlier for the benefit of the mother’s and infant’s health.

Traumatic birth and counselling

Only recently has traumatic birth been recognised to develop Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), with one third who experience traumatic births develop PTSD [5-8] and affecting 3% of new mothers [9]. Although “there is no consistent definition of traumatic birth and no systematic way to assess birth trauma…” [6] it can lead to long term mother and infant health risk problems [5,8,10]. In the immediate concern, particularly in this case, the development of clinically significant symptoms of PTSD were rippled through the postpartum period.

The issue for the mother after the traumatic birth was the lack of acknowledgment or support while in the hospital environment prior to discharge. “Women are often traumatised as a result of the actions or inactions of midwives, nurses and doctors” [6] and as a result only 13.5% of women report that staff ask about their mental health after birth and half perceive that staff encourage them to ask questions about birth [7].

It is unequivocally supported that postpartum counselling following a distressing or traumatic birth can be mutually beneficial for the mother and infant [7,11]. This can be an opportunity for early intervention and mitigation of the development PTSD and PPD.

With 3% experiencing PTSD from childbirth there are many other implications that can mutually benefit the health care system [9]. In Turkstra et al. [12] study they found that healthcare utilisation was higher during childbirth for women with traumatic birth with longer postpartum hospital stays (3.2 vs 2.6 days) and that effects were still significant one year after childbirth with increased health care utilisation [12]. This creates an economic burden to the healthcare system that could, otherwise be intervened and mitigated at the root source.

There are many circumstances that could influence whether or not Winnie would have developed postpartum depression, however, it is clear that implementing a best practice of follow up counselling or discussion following birth while in the hospital could greatly reduce the likelihood.

Indirect care – pediatricians

Indirect care is health care providers who do not provide direct care to a mother such as pediatricians, but are resources that could be invaluable to early identification and intervention of PPD. Parents may hide mental health problems to appear “normal” or competent [13], often because parents feel judged or stigmatised. However, pediatricians do not recognise most mothers with high levels of self-reported depression and cannot identify depressive symptoms without a screening tool [14]. Except for one postpartum visit women do not see health providers regularly except through children’s services such as pediatricians [15]. This is a lost opportunity for an indirect health care provider for mothers to identify and intervene for PPD.

In Grigoriadis et al. [16] study they found that fewer than half that died by suicide during pregnancy or postpartum had mental health service use in the 30 days before death, but a substantial proportion had contact with other health care professionals such as pediatricians [16]. This is critical to understand that the standard of care is low visits for postpartum mothers but there are other health care providers that are engaged who could provide an alternative for identification and intervention of PPD. In essence, “pediatricians may be an underused resource to mothers regarding these issues” [17].

Health care professionals agree that the mother’s emotional health greatly affects her child’s wellbeing. “Pediatricians prefer to rely on other professionals, particularly social workers, to address maternal depression…” [18] with only 7% feeling responsible to treat maternal depression and 39% felt a pediatric setting is not ideal.

It would be fruitful to ensure that pediatricians are trained in PPD identification and given the appropriate tools to intervene such as referrals to resources that are best suited for the mother, such as psychiatry. Although it can be challenging focusing on the mother with a difficult infant present, indirect providers have an opportunity to help identify postpartum depression in mothers.

Screening, follow up and referral systems

Access to Canadian perinatal mental health services is disparate across provinces and territories and without routine screening, three-quarters of women meeting the definition of postpartum are not identified and only 10% requiring care for postpartum depression receive it [19]. In this case early symptoms were identified but no follow up or referral was given. The minimisation of the mother’s level of depression was negated to baby blues and “normal.” “Mental health care is provided only when women seek it, or when health professionals identify symptoms worthy of clinical attention…” [20].

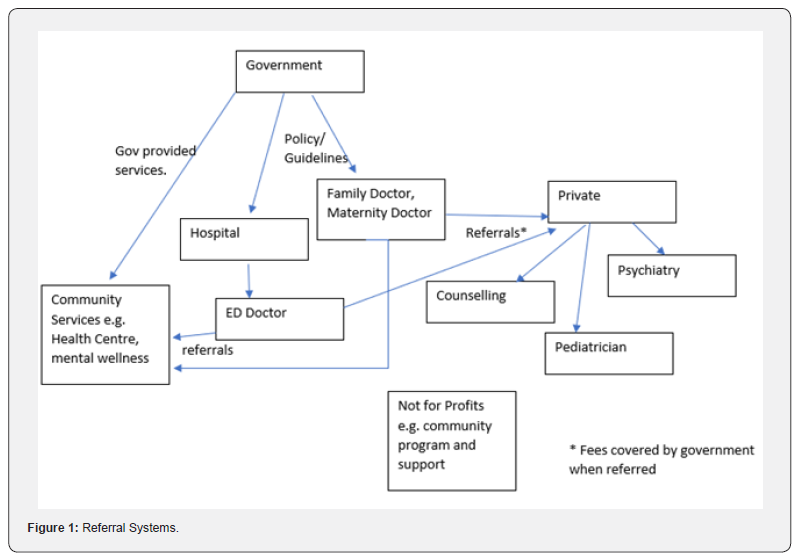

Winnie did not meet various health care provider’s idea of PPD and was thus not intervened. With multiple providers, including specialised care providers, one should have taken Winnie’s mental health into consideration and followed up, however, the system is so complex and fragmented its difficult to see Winnie’s overall health picture (Refer to Figure 1). If reviewing Winnie’s timeline it is obvious to note her mental health deterioration, however, if the mother received different providers over the weeks postpartum, how was the system supposed to catch this?

Collaboration amongst service providers is critical and according to the 2012 Commonwealth Fund survey, Canada was last among the 11 countries analysed on the number of doctors able to access or exchange patient records with other doctors [21]. More immediate and regular follow up is necessary to ensure that mothers receive perinatal health care quickly and frequently. “Only a third of women with a diagnosable mental disorder at their first antenatal appointment had any contact with mental health services during pregnancy or up to 3 months” [22].

Could this have been prevented with earlier PPD screenings? Canada does not have a perinatal mental health screening guideline and thus only 87% of health care professional have workplace mandated screening, but 66% use a validated tool [23].

As seen in Figure 1, the complex nature of the health care system for following postpartum care is difficult to navigate and creates unnecessary boundaries and obstacles to care for mothers. Although the system structure and systemic problems such as lack of integrated and shared medical records or collaborative, holistic continuity of care are absent, could mean that small changes will make a big difference. If screening tools are implemented early and regularly, mothers can be better captured by the system.

Through the use of EDPS, a sequential picture of Winnie’s experience of postpartum depression may have revealed the worsening symptoms and allowed for earlier interventions. Another key indicator of the siloed health care practitioner system meant that there was little or no follow up care for Winnie. Putting in place systems that ensure follow up care is undertaken would critically reduce the number of mothers impacted by postpartum depression. Throughout Winnie’s experience there was ample opportunity for the maternity doctor, pediatrician, ER doctor and others to identify the onset of postpartum depression.

Conclusion

Our examination has stressed the urgent need for a national strategy and standardized guidelines to provide a cohesive framework for healthcare practitioners. Such foundations would facilitate collaboration, streamline communication, and ensure continuity of care, thereby empowering providers to identify and intervene in postpartum depression with precision and compassion. Winnie’s scenario is similar to many women and highlights a critical need to implement change now. The urgency of this call to action cannot be overstated, as each day without adequate support prolongs the suffering of mothers like Winnie and perpetuates a cycle of maternal distress and unmet needs.

However, there are actionable recommendations laid out in this paper offer a proposal for tangible progress. By prioritizing the implementation of post-birth counseling standards, investing in the training and education of indirect care providers such as pediatricians, and instituting systematic screening protocols for postpartum depression, we can begin to dismantle the barriers that impede timely intervention and support.

In conclusion, Winnie's story serves as both a rallying call and a catalyst for change. As we confront the daunting challenge of postnatal depression within Canada's perinatal healthcare system, let us heed the lessons learned from her journey and increase our efforts to create a future where every mother receives the support, understanding, and care she deserves. The time for action is now, and together, we can build a brighter, healthier future for generations to come.

Declaration

Conflict of interest disclosure statement: The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Competing interests: No competing interests of authors listed.

Funding information: No funding was received by any of the authors or by any of the agencies/parties.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources: No material was reproduced from other sources.

References

- PHAC, P. H. A. o. C. (2012) Canadian Hospitals Maternity Policies and Practices Survey. P. H. A. o. Canada.

- RNAO, R. N. A. o. O. (2018) Assessment and Interventions for Perinatal Depression. Toronto (ON)

- Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, et al. (2011) The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 11: 100.

- Yin RK (2018) Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage Publications.

- Bailham D, Joseph S (2003) Post-traumatic stress following childbirth: A review of the emerging literature and directions for research and practice. Psychology, Health & Medicine 8(2): 159-168.

- Elmir R, Schmied V, Wilkes L, Jackson D (2010) Women's perceptions and experiences of a traumatic birth: a meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs 66(10): 2142-2153.

- Gamble J, Creedy DK (2009) A counselling model for postpartum women after distressing birth experiences. Midwifery 25(2): e21-e30.

- Hendrix Y, van Dongen KSM, de Jongh A, van Pampus MG (2021) Postpartum Early EMDR therapy Intervention (PERCEIVE) study for women after a traumatic birth experience: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 22(1): 599.

- PHAC, P. H. A. o. C. (2023) Family Centred Maternity and Newborn care: National Guidelines; Chapter 5: Postpartum Care. P. H. A. o. Canada.

- Johansson M, Benderix Y, Svensson I (2020) Mothers' and fathers' lived experiences of postpartum depression and parental stress after childbirth: a qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 15(1): 1722564.

- Townsend ML, Brassel AK, Baafi M, Grenyer B (2020) Childbirth satisfaction and perceptions of control: postnatal psychological implications. British Journal of Midwifery 28(4): 225-233.

- Turkstra E, Creedy DK, Fenwick J, Buist A, Scuffham PA, et al. (2015) Health services utilization of women following a traumatic birth. Arch Womens Ment Health 18(6): 829-832.

- Cooper C, Tchernegovski P, Hine R (2023) “The validation is not enough”: Australian mothers’ views and perceptions of mental health support from psychologists in private practice. Clinical Psychologist 27(3): 392-403.

- Heneghan AMSEJ, Bauman LJ, Stein REK (2000) Do Pediatricians Recognize Mothers with Depressive Symptoms? Pediatrics 106(6): 1367-1373.

- Chaudron LH (2003) Postpartum Depression: What Pediatricians Need to Know. Pediatrics in Review 24(5): 154-161.

- Grigoriadis S, Wilton AS, Kurdyak PA, Rhodes AE, Vonder Porten EH, et al. (2017) Perinatal suicide in Ontario, Canada: a 15-year population-based study. CMAJ 189(34): E1085-E1092.

- Heneghan AM, Mercer MB, DeLeone NL (2004) Will Mothers Discuss Parenting Stress and Depressive Symptoms with their child’s Pediatrician? Pediatrics 113(3 Pt 1): 460-467.

- Heneghan AM, Morton S, DeLeone NL (2007) Paediatricians' attitudes about discussing maternal depression during a paediatric primary care visit. Child Care Health Dev 33(3): 333-339.

- DeRoche C, Hooykaas A, Ou C, Charlebois J, King K (2023) Examining the gaps in perinatal mental health care: A qualitative study of the perceptions of perinatal service providers in Canada. Front Glob Womens Health 4: 1027409.

- Fonseca A, Gorayeb R, Canavarro MC (2015) Women׳s help-seeking behaviours for depressive symptoms during the perinatal period: Socio-demographic and clinical correlates and perceived barriers to seeking professional help. Midwifery 31(12): 1177-1185.

- Liddy C, Hogel M, Blazkho V, Keely E (2015) The current state of electronic consultation and electronic referral systems in Canada: an environmental scan. Global Telehealth 2015: Integrating Technology and Information for Better Healthcare 209: 75-83.

- Lee-Carbon L, Nath S, Trevillion K, Byford S, Howard LM, et al. (2022) Mental health service use among pregnant and early postpartum women. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57(11): 2229-2240.

- Hicks LM, Ou C, Charlebois J, Tarasoff L, Pawluski J, et al. (2022) Assessment of Canadian perinatal mental health services from the provider perspective: Where can we improve? Front Psychiatry 13: 929496.